Open Jennings Diss Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE VIKINGS in ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell

THE VIKINGS IN ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell Introduction In recent years, it has been suggested that the first permanent Scandinavian presence in Orkney was not the result of forcible land-taking by Vikings, but came about instead through gradual penetration - a period which has been described as one of'informal' settlement (Morris 1985: 213; 1998: 83). Such would have involved a phase of co-existence, or even integration, between the native Picts and the earliest Norse settlers. This initial period, it is supposed, was then followed by 'a second, formal, settlement associated with the estab lishment of an earldom' (Morris 1998: 83 ), in the late 9'h century. The archaeological evidence advanced in support of the first 'period of overlap' is, however, open to alternative interpretation and, indeed, Alfred Smyth has com mented ( 1984: 145), in relation to the annalistic records of the earliest Viking attacks on Ireland, that these 'strongly suggest that the Norwegians did not gradually infiltrate the Northern Isles as farmers and fisherman and then sud denly tum nasty against their neighbours'. Others have supposed that the first phase of Norse settlement in Orkney would have involved, in the words of Buteux (1997: 263): 'ness-taking' (the fortifying of a headland by means of a cross-dyke) and the occupation of small off-shore islands. Crawford ( 1987: 46) argues that headland dykes on Orkney can be interpreted as indicating ness-taking. However many are equally likely to be prehistoric land boundaries, and no bases on either headlands or small islands have yet been positively identified. Buteux continues his discussion by observing, most pertinently, that: While this can not be taken as suggesting that such sites do not remain to be uncovered, the striking fact is that almost all identified Viking-period settlements in the Northern Isles are found overlying or immediately adjacent to sites which were occupied in the preceding Pictish period and which, furthermore, had frequently been settlements of some size and importance. -

Building Warrants Received: May 2021

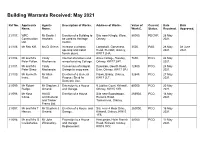

Building Warrants Received: May 2021 Ref No. Applicants Agents Description of Works. Address of Works. Value of Current Date Date Name. Name. Work £. Status. Received. Approved. 21/107. WRC Mr Bashir I Erection of a Building to Site near Kringlo, Wyre, 85000. RECNP. 28 May Construction Hasham. be used as Heritage Orkney. 2021. Ltd. Centre. 21/106. Mr Rob Kiff. Ms Di Grieve. Increase a window Langskaill, Gorseness 3500. PAS. 28 May 08 June opening and install Road, Rendall, Orkney, 2021. 2021. french doors. KW17 2HA. 21/104. Mr and Mrs Cindy Internal alterations and Alma Cottage, Sanday, 7600. PCO. 24 May Peter Fallon. Mackenzie. re-roof existing Cottage. Orkney, KW17 2AY. 2021. 21/101. Mr and Mrs Cindy Conversion of integral Dykeside, Georth Road, 12500. PCO. 24 May Peter Shaw. Mackenzie. Garage to snug area. Evie, Orkney, KW17 2PJ. 2021. 21/100. Mr Kenneth Mr Allan Erection of a General Flaws, Birsay, Orkney, 32848. PCO. 27 May Irvine. Reid. Purpose Shed for KW17 2LT. 2021. Domestic Use. 21/099. Mr Robert Mr Stephen J Extension to a House 9 Jubilee Court, Kirkwall, 80000. PCO. 20 May Budge. Omand. and Garage. Orkney, KW15 1XR. 2021. 21/098. Mr Ross HAUS Erection of a House. Site near Boondatoon, 266902. PCO. 18 May Corse. Architectural Rerwick Road, 2021. and Timber Tankerness, Orkney. Frame Ltd. 21/097. Mr and Mrs T Mr Stephen J Erection of a House and Site near 4 Moar Drive, 260000. PCO. 18 May Harcus. Omand. Garage. Kirkwall, Orkney, KW15 2021. 1FS. 21/096. Mr and Mrs G Mr John Extension to a House Hescombe, Holm Branch 30000. -

Cruising the ISLANDS of ORKNEY

Cruising THE ISLANDS OF ORKNEY his brief guide has been produced to help the cruising visitor create an enjoyable visit to TTour islands, it is by no means exhaustive and only mentions the main and generally obvious anchorages that can be found on charts. Some of the welcoming pubs, hotels and other attractions close to the harbour or mooring are suggested for your entertainment, however much more awaits to be explored afloat and many other delights can be discovered ashore. Each individual island that makes up the archipelago offers a different experience ashore and you should consult “Visit Orkney” and other local guides for information. Orkney waters, if treated with respect, should offer no worries for the experienced sailor and will present no greater problem than cruising elsewhere in the UK. Tides, although strong in some parts, are predictable and can be used to great advantage; passage making is a delight with the current in your favour but can present a challenge when against. The old cruising guides for Orkney waters preached doom for the seafarer who entered where “Dragons and Sea Serpents lie”. This hails from the days of little or no engine power aboard the average sailing vessel and the frequent lack of wind amongst tidal islands; admittedly a worrying combination when you’ve nothing but a scrap of canvas for power and a small anchor for brakes! Consult the charts, tidal guides and sailing directions and don’t be afraid to ask! You will find red “Visitor Mooring” buoys in various locations, these are removed annually over the winter and are well maintained and can cope with boats up to 20 tons (or more in settled weather). -

Ferry Timetables

1768 Appendix 1. www.orkneyferries.co.uk GRAEMSAY AND HOY (MOANESS) EFFECTIVE FROM 24 SEPTEMBER 2018 UNTIL 4 MAY 2019 Our service from Stromness to Hoy/Graemsay is a PASSENGER ONLY service. Vehicles can be carried by prior arrangement to Graemsay on the advertised cargo sailings. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Stromness dep 0745 0745 0745 0745 0745 0930 0930 Hoy (Moaness) dep 0810 0810 0810 0810 0810 1000 1000 Graemsay dep 0825 0825 0825 0825 0825 1015 1015 Stromness dep 1000 1000 1000 1000 1000 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1030 1030 1030 1030 1030 Graemsay dep 1045 1045 1045 1045 1045 Stromness dep 1200A 1200A 1200A Graemsay dep 1230A 1230A 1230A Hoy (Moaness) dep 1240A 1240A 1240A Stromness dep 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 Graemsay dep 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 Stromness dep 1745 1745 1745 1745 1745 Graemsay dep 1800 1800 1800 1800 1800 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1815 1815 1815 1815 1815 Stromness dep 2130 Graemsay dep 2145 Hoy (Moaness) dep 2200 A Cargo Sailings will have limitations on passenger numbers therefore booking is advisable. These sailings may be delayed due to cargo operations. Notes: 1. All enquires must be made through the Kirkwall Office. Telephone: 01856 872044. 2. Passengers are requested to be available for boarding 5 minutes before departure. 3. Monday cargo to be booked by 1600hrs on previous Friday otherwise all cargo must be booked before 1600hrs the day before sailing. Cargo must be delivered to Stromness Pier no later than 1100hrs on the day of sailing. -

Summary Register of Occasional Licences

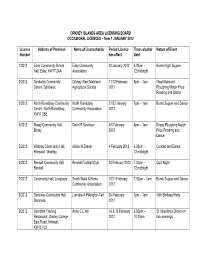

ORKNEY ISLANDS AREA LICENSING BOARD OCCASIONAL LICENCES – from 1 JANUARY 2012 Licence Address of Premises Name of Licenceholder Period Licence Times alcohol Nature of Event Number has effect Sold 1/2012 Eday Community School Eday Community 28 January 2012 6.30pm – Burns Night Supper Hall, Eday, KW17 2AA Association 12 midnight 2/2012 Sandwick Community Orkney West Mainland 11/12 February 8pm – 1am West Mainland Centre, Sandwick Agricultural Society 2012 Ploughing Match Prize Reading and Dance 3/2012 North Ronaldsay Community North Ronaldsay 21/22 January 7pm – 1am Burns Supper and Dance Centre, North Ronaldsay, Community Association 2012 KW17 2BE 4/2012 Birsay Community Hall, David R Davidson 4/5 February 8pm – 1am Birsay Ploughing Match Birsay 2012 Prize Reading and Dance 5/2012 Westray Community Hall, Alison M Drever 4 February 2012 6.30pm – Concert and Dance Pierowall, Westray 12 midnight 6/2012 Rendall Community Hall, Rendall Football Club 24 February 2012 7.30pm – Quiz Night Rendall 12 midnight 7/2012 Community Hall, Longhope South Walls & Brims 10/11 February 7.30pm – 1am Burns Supper and Dance Community Association 2012 8/2012 Stenness Community Hall, Lorraine A Pilkington-Tait 3/4 February 7pm – 1am 50th Birthday Party Stenness 2012 9/2012 Overblikk Training Anne C L Hill 14 & 16 February 6.30pm – St Valentines Dinner on Restaurant, Orkney College, 2012 10.30pm two evenings East Road, Kirkwall, KW15 1LX 10/2012 Deerness Community Gareth L Crichton 3/4 March 2012 8pm – 1am Concert and Dance Centre, Deerness, KW17 2QH 11/2012 Orphir -

National Retailers.Xlsx

THE NATIONAL / SUNDAY NATIONAL RETAILERS Store Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Post Code M&S ABERDEEN E51 2-28 ST. NICHOLAS STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1BU WHS ST NICHOLAS E48 UNIT E5, ST. NICHOLAS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW SAINSBURYS E55 UNIT 1 ST NICHOLAS CEN SHOPPING CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW RSMCCOLL130UNIONE53 130 UNION STREET ABERDEEN, GRAMPIAN AB10 1JJ COOP 204UNION E54 204 UNION STREET X ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY CONV E54 SOFA WORKSHOP 206 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY ALF PL E54 492-494 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1TJ TESCO DYCE EXP E44 35 VICTORIA STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1UU TESCO HOLBURN ST E54 207 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BL THISTLE NEWS E54 32 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BT J&C LYNCH E54 66 BROOMHILL ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6HT COOP GT WEST RD E46 485 GREAT WESTERN ROAD X ABERDEEN AB10 6NN TESCO GT WEST RD E46 571 GREAT WESTERN ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6PA CJ LANG ST SWITIN E53 43 ST. SWITHIN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6XL GARTHDEE STORE 19-25 RAMSAY CRESCENT GARTHDEE ABERDEEN AB10 7BL SAINSBURY PFS E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA ASDA BRIDGE OF DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA SAINSBURY G/DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA COSTCUTTER 37 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BN RS MCCOLL 17UNION E53 17 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BU ASDA ABERDEEN BEACH E55 UNIT 11 BEACH BOULEVARD RETAIL PARK LINKS ROAD, ABERDEEN AB11 5EJ M & S UNION SQUARE E51 UNION SQUARE 2&3 SOUTH TERRACE ABERDEEN AB11 5PF SUNNYS E55 36-40 MARKET STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5PL TESCO UNION ST E54 499-501 -

Register of Sea Fishing Boats

Register of Sea Fishing Boats (Orkney Archives CE55/11) Vessel name and/or number Port Registry Date Name of owner Name of Master/Skipper Archive Ref Page 0 K196 Kirkwall 08/10/1888 George Grey George Gray CE55/11/6 46 K275 South Ronaldsay 28/05/1913 John Cursator, George John Cursator CE55/11/9 236 W. Cursator and James Robertson K422 Kirkwall 14/08/1890 James Scott James Scott CE55/11/6 130 K426 Kirkwall 24/09/1890 James Banks Bruce James B. Bruce CE55/11/7 2 ? 181 Papa Westray 18/12/1934 John Bursiter John Bursiter CE55/11/17 101 ? 331 Kirkwall 24/11/1933 John Harcus John Harcus CE55/11/17 81 ? 88 Westray 23/05/1934 James and George George Rendall CE55/11/17 89 Rendall Aberdeen K486 Kirkwall 21/09/1892 Robert Garden John Arcus CE55/11/7 49 Acorn K556 Kirkwall 28/04/1897 George Robertson Eric Sutherland CE55/11/7 113 Active K168 Kirkwall 04/07/1907 G. R. C. Russell David Finlayson CE55/11/9 119 Active K231 St Margaret's Hope 29/06/1874 John Oman & others John Oman CE55/11/5 30 Activer K398 Kirkwall 04/06/1890 William Mowat William Mowat CE55/11/6 119 ADA 135 Sandy 27/09/1927 James W. Sinclair James W. Sinclair CE55/11/16 167 Admiral K144 Kirkwall 08/02/1900 Benjamin Thomson and Benjamin Thomson CE55/11/8 145 James Simpson Adventine 174 kirkwall 24/05/1928 Daniel Johnston Daniel Johnston CE55/11/17 2 Adventure 174 Kirkwall 02/12/1929 George Smith George Smith CE55/11/17 25 Adventure K17 Holm 23/02/1887 David Woldradge David Woldradge CE55/11/5 3 Adventure K181 Kirkwall 21/02/1900 William Skea William Skea CE55/11/8 159 Adventure K262 Kirkwall 21/05/1889 Thomas Hewison Thomas Hewison CE55/11/6 79 22 October 2011 Page 1 of 84 Vessel name and/or number Port Registry Date Name of owner Name of Master/Skipper Archive Ref Page Adventure K527 Tankerness 07/06/1904 John Voy John Voy CE55/11/9 42 Afram K682 North Ronaldsay 06/06/1947 Hugh Thomson H. -

Orkney Greylag Goose Survey Report 2015

The abundance and distribution of British Greylag Geese in Orkney, August 2015 A report by the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust to Scottish Natural Heritage Carl Mitchell 1, Alan Leitch 2, & Eric Meek 3 November 2015 1 The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, Gloucester, GL2 7BT 2 The Willows, Finstown, Orkney, KY17, 2EJ 3 Dashwood, 66 Main Street, Alford, Aberdeenshire, AB33 8AA 1 © The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This publication should be cited as: Mitchell, C., A.J. Leitch & E. Meek. 2015. The abundance and distribution of British Greylag Geese in Orkney, August 2015. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Report, Slimbridge. 16pp. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Gloucester GL2 7BT T 01453 891900 F 01453 890827 E [email protected] Reg. Charity no. 1030884 England & Wales, SC039410 Scotland 2 Contents Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Methods ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Field counts ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Kirk in the Garden of Evie

THE KIRK IN THE GARDEN OF EVIE A Thumbnail Sketch of the History of the Church in Evie Trevor G Hunt Minister of the linked Churches of Evie, Firth and Rendall, Orkney First Published by Evie Kirk Session Evie, Orkney. 1987 Republished 1996 ComPrint, Orkney 908056 Forward to the 1987 Publication This brief history was compiled for the centenary of the present Evie Church building and I am indebted to all who have helped me in this work. I am especially indebted to the Kirk’s present Session Clerk, William Wood of Aikerness, who furnished useful local information, searched through old Session Minutes, and compiled the list of ministers for Appendix 3. Alastair Marwick of Whitemire, Clerk to the Board, supplied a good deal of literature, obtained a copy of the Title Deeds, gained access to the “Kirk aboon the Hill”, and conducted a tour (even across fields in his car) to various sites. He also contributed valuable local information and I am grateful for all his support. Thanks are also due to Margaret Halcro of Lower Crowrar, Rendall, for information about her name sake, and to the Moars of Crook, Rendall, for other Halcro family details. And to Sheila Lyon (Hestwall, Sandwick), who contributed information about Margaret Halcro (of the seventeenth century!). TREVOR G HUNT Finstown Manse March 1987 Foreword to the 1996 Publication Nearly ten years on seemed a good time to make this history available again, and to use the advances in computer technology to improve its appearance and to make one or two minor corrections.. I was also anxious to include the text of the history as a page on the Evie, Firth and Rendall Churches’ Internet site for reference and, since revision was necessary to do this, it was an opportunity to republish in printed form. -

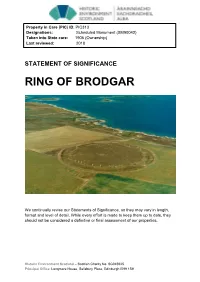

Ring of Brodgar

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC313 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90042) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2018 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE RING OF BRODGAR We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH RING OF BRODGAR, STONE CIRCLE AND HENGE BRIEF DESCRIPTION The monument comprises a massive ceremonial enclosure, or ‘henge’; its rock-cut ditch (c.123m diameter) encircling a platform with an impressive stone circle set around its circumference. -

2018 50Th Anniversary Issue

Orkney Heritage Society 1968-2018 50th Anniversary Issue Objectives of the Orkney Heritage Society The aims of the Society are to promote and encourage the following objectives by charitable means: 1. To stimulate public interest in, and care for the beauty, history and character of Orkney. 2. To encourage the preservation, development and improvement of features of general public amenity or historical interest. 3. To encourage high standards of architecture and town planning in Orkney. 4. To pursue these ends by means of meetings, exhibitions, lectures, conferences, publicity and promotion of schemes of a charitable nature. New members are always welcome To learn more about the society and its ongoing work, check out the regularly updated website at www.orkneycommunities.co.uk/ohs or contact us at Orkney Heritage Society PO Box No. 6220 Kirkwall Orkney KW15 9AD Front Cover: Robert Garden and his wife, Margaret Jolly, along with one of their daughters standing next to the newly re-built Groatie Hoose. It got its name from the many shells, including ‘groatie buckies’, decorating the tower. Note the weather vane showing some of Garden’s floating shops. Photo gifted by Mrs Catherine Dinnie, granddaughter of Robert Garden. 1 Orkney Heritage Society Committee 2018 President: Sandy Firth, Edan, Berstane Road, Kirkwall, KW15 1NA [email protected] Vice President: Sheena Wenham, Withacot, Holm [email protected] Chairman: Spencer Rosie, 7 Park Loan, Kirkwall, KW15 1PU [email protected] Vice Chairman: David Murdoch, 13 -

Buxa Chalets Copy

B U X A F A R M CHALETS Self-Catering accommodations How to get here From Stromness: When departing the ferry in Stromness turn right upon departure from the ferry parking lot onto the A965 taking you towards Kirkwall. Take the 3rd left off the traffic circle and take a right at the end of the road. Turn right at A964 signposted to Orphir. Continue for approximately 5 miles and Buxa Farm Chalets is signposted on the right. Go to the end of the road and take a left at next signpost. Approximately 15 minutes. If What is there to see and do? using GPS use postcode: KW17 2RD From Kirkwall: When departing the ferry in Kirkwall turn left upon departure from the ferry parking lot and head through industrial park (taking you towards Kirkwall) to The most common complaint we get from visitors is junction, take left and then 2nd left off traffic circle at Mills that there just isn’t enough time to see everything in Filling Station and follow road to another traffic circle and Orkney! We suggest before you visit that you log on to take 2nd left. Take a right at the A964 Orphir road and the local tourist information site: stay on for about 20 minutes passing through small www: visitorkney.com that is just chock full of village of Orphir and uphill past Houton Ferry Terminal. information on what to see and do in Orkney. Buxa Farm Chalets is signposted on the left. Go to the Alternatively you can phone the VisitOrkney tourist end of the road and take a left at next signpost.