The Deep Roots of the Depreciation of the Syrian Pound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria Country Office

SYRIA COUNTRY OFFICE MARKET PRICE WATCH BULLETIN July 2020 ISSUE 68 Picture @ WFP/Hussam Al Saleh @WFP/Jessica Lawson Highlights Standard Food Basket Figure 1: Food basket cost and changes, SYP ○ The national average price of a stand- The national average price of a standard reference 1 ard reference food basket in July 2020 food basket increased by three percent between June and July 2020, reaching SYP 86,571. The highest rate was SYP 86,571 (USD 69 at the official recorded since the start of the crisis. The national av- exchange rate 1,250/USD), increasing by erage food basket price was 131 percent higher than three percent compared to June 2020. that of January 2020 and was 251 percent higher com- The reference food basket price in- pared to July 2019 (Figure 1). creased by 251 percent since July 2019. Compared to June 2020, July food basket prices have ○ The national average ToT between been relatively constant due to the arrival of the coun- wheat flour and daily non-skilled wage try’s main agricultural harvest and the strengthening labour, a proxy indicator for purchasing of the informal exchange rate. power, reached its lowest level since While seven governorates reported an increasing aver- Chart 1: National min., max. and average food basket cost, SYP monitoring began (2014). In July 2020 a age reference food basket price in July 2020, five gov- daily non-skilled wage could afford only ernorates reported a decreasing average reference 3.91kgs of wheat flour compared to food basket and two governorates reported no change 8.83kgs in July 2019. -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

President Obama's Approach to the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Absence Paul Williams

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 48 | Issue 1 2016 President Obama's Approach to the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Absence Paul Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Paul Williams, President Obama's Approach to the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Absence, 48 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 83 (2016) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol48/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 48 (2016) President Obama’s Approach to the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Absence Paul Williams* Many commentators argue that the White House does not have a policy regarding the Middle East and North Africa. Based on observations of the White House’s foreign policy decisions over a breadth of seven years, this article argues that The White House does have a clear policy and it is one of Strategic Absence. The term Strategic Absence is used to describe political behavior that arises from a belief that sometimes, in foreign affairs, it is better to be absent rather than present. Strategic Absence has led to a degradation of American influence in the Middle East and has contributed to deteriorating conflict situations in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya. -

Sourcing the Arab Spring: a Case Study of Andy Carvin's Sources During the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions

Sourcing the Arab Spring: A Case Study of Andy Carvin’s Sources During the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions Paper presented at the International Symposium on Online Journalism in Austin, TX, April 2012 Alfred Hermida Associate professor, Graduate School of Journalism, University of British Columbia Seth C. Lewis Assistant professor, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Minnesota Rodrigo Zamith Doctoral student, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Minnesota Contact: Alfred Hermida UBC Graduate School of Journalism 6388 Crescent Road Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z2 Canada Tel: 1 604 827 3540 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper presents a case study on the use of sources by National Public Radio's Andy Carvin on Twitter during key periods of the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings. It examines the different actor types on the social media platform to reveal patterns of sourcing used by the NPR social media strategist, who emerged as a key broker of information on Twitter during the Arab Spring. News sourcing is a critical element in the practice of journalism as it shapes from whom journalists get their information and what type of information they obtain. Numerous studies have shown that journalists privilege elite sources who hold positions of power in society. This study evaluates whether networked and distributed social media platforms such as Twitter expand the range of actors involved in the construction of the news through a quantitative content analysis of the sources cited by Carvin. The results show that non-elite sources had a greater influence over the content flowing through his Twitter stream than journalists or other elite sources. -

Young Global Leaders Annual Summit List of Participants

Young Global Leaders Annual Summit Yangon & Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar 3-5 June 2013 List of Participants As of 24 April 2013 Reuben Abraham Executive Director, Centre for Indian School of India Emerging Markets Solutions Business Tony Abrahams Co-Founder and Chief Executive Ai-Media Australia Officer Anu Acharya Founder and Chief Executive Officer mapmygenome.in India Vikram K. Akula Director AgSri Agricultural USA Services Pvt. Ltd Biola Alabi Managing Director, Africa Electronic Media Nigeria Network (M-Net) Suryani Senja Founder and Managing Director CULT Sdn Bhd Malaysia Alias Wilmot Allen Founder 1 World Enterprises USA Jamil Anderlini Beijing Bureau Chief The Financial Times People's Republic of China Martin Aspillaga Managing Director Salkantay Partners Peru Solomon Assefa Research Scientist IBM Thomas J. Watson USA Research Center Alexander Head, Fast Growth Markets and SAP AG People's Republic Atzberger China Strategy of China Asli Ay Managing Partner US Policy Metrics LLC USA Gina Badenoch Founder and Chief Executive Officer Ojos que Sienten AC Mexico Analisa Balares Chief Executive Officer and Founder Womensphere and USA Womensphere Foundation Jeremy Balkin President Karma Capital Australia Miranda A. Director of Sustainability, Wal-Mart Stores Inc. USA Ballentine Renewable Energy and Sustainable Facilities Katinka Barysch Deputy Director Centre for European United Kingdom Reform (CER) Karen Bell Managing Director and Head of Deutsche Bank AG Singapore Regional Management for Group Technology and Operations Jacques Beltran Senior Vice-President, Europe, CIS, Alstom International France Turkey Sasja Beslik Chief Executive Officer, Nordea Nordea Bank AB Sweden Investment Funds Neil Blumenthal Co-Founder and Co-Chief Executive Warby Parker Eyewear USA Officer David Boehmer Regional Managing Partner, Heidrick & Struggles USA Financial Services Jesmane Founder and Director Harvest USA Boggenpoel Bunty Bohra Chief Executive Officer Goldman Sachs India Services Private Limited Thomas J. -

To the OPC Holiday Party OPC in California and Paris

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • December 2015 Journalist Safety Panel Highlights Growing Risks EVENT RECAP invulnerability you had, that press pass – that magical By Chad Bouchard thing that gave you this sort With violence against journalists of force field – that’s gone.” soaring to an all-time high in recent He called for more pres- years, freelancers and mainstream news media are seeking better ways sure from governments, to protect and give them the support and added that many of the they need to do their jobs. worst jailers of journalists Chad Bouchard On Dec. 16, the OPC, Bloomberg around the world are allies of the U.S. Left to right: Ambassador Raimonda Murmokaite, LLP and the Ford Motor Company Joel Simon, Anna Therese Day, Gregory D. co-sponsored a discussion about “They’re countries like Johnsen and Lara Setrakian. Egypt – which is the second journalist safety with a panel of jour- free speech. “We have to make noise leading jailer of journalists – Turkey, nalists and press freedom advocates. about this at all possible levels,” she In 2015, 69 journalists were Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia. These are said. “Those who can’t stand the killed and 199 jailed worldwide, ac- countries where the U.S. has signifi- right to free information will never cording to the Committee to Protect cant influence, and it should be exer- defend the journalists.” Journalists. cising that influence.” Anna Therese Day, a freelance Joel Simon, the CPJ’s executive The panel also included Ambas- journalist and a founding board director, told attendees that jour- sador Raimonda Murmokaite, Lith- member of the Frontline Freelance nalists are increasingly targeted be- uania’s permanent representative Register, applauded work from cause of shifting power in the cur- to the UN. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Syria Country Office

SYRIA COUNTRY OFFICE MARKET PRICE WATCH BULLETIN June 2020 ISSUE 67 @WFP/Jessica Lawson Picture @ WFP/Hussam Al Saleh Highlights Standard Food Basket Figure 1: Food basket cost and changes, SYP ○ The national average price of a stand- The national average monthly price of a standard ref- erence food basket1 increased by 48 percent between ard reference food basket in June 2020 May and June 2020, reaching SYP 84,095. The national was SYP 84,095 increasing by 48 percent average food basket price was 110 percent higher than compared to May 2020. The national that of February 2020 (before COVID-19 movement average reference food basket price restrictions) and was 231 percent higher compared to increased by 110 percent since February October 2019 (start of the Lebanese financial crisis) 2020 (pre-COVID-19 period). and 240 percent higher vis-à-vis June 2019 (Figure 1). ○ WFP’s reference food basket is now The increase in the national average food basket price more expensive than the highest gov- is caused by a multitude of factors such as: high fluctu- ernment monthly salary (SYP 80,240). ations of the Syrian pound on the informal exchange Outlining the serious deterioration in market, intensification of unilateral coercive measures Chart 1: National min., max. and average food basket cost, SYP peoples’ purchasing power. and political disagreements within the Syrian Elite. ○ The Syrian pound continued to heavily All 14 governorates reported an increasing average depreciate on the informal exchange reference food basket price in June 2020, with the market, weakening to SYP 3,200/USD highest month-on-month (m-o-m) increase reported in before stabilizing around SYP 2,500/USD Quneitra (up 78 percent m-o-m), followed by Rural by end June. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

Syriaeconomicreport

SyriaEconomicReport SYRIA’S MACROECONOMIC PROGRESS NOT TO OVERSHADOW ITS DRASTIC REFORM REQUIREMENTS u The Syrian economy is currently witnessing an improvement in output performance, though still far below the prevailing potential of the economy. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Syria’s real GDP growth rate has reported close to 3% in 2005 (4.5% according to official Syrian estimate). It is worth recalling that the Syrian economy had reported an average real GDP growth of 1.8% per annum, according to the same figures, over the period extending from 1999 to 2004. Non-oil GDP growth may have risen to about 5.5% in 2005, from 5% in 2004 according to the IMF, mainly driven by business investment, household consumption and non-oil exports. Despite the relative improvement in economic conditions, Syria’s September private demand continues to suffer from the lack of adequate financing, restricting its leverage effect on growth, and from a below potential private consumption and investment component in view of prevailing uncertainties. u Over the past year, the Syrian economy has benefited from rising oil prices and a regional post-Iraq war boom translating into 2006 larger inflows emanating from workers remittances, tourist receipts and foreign investment activity. However, the widening political uncertainties and the drastic reform requirements, despite the progress recently reported, continued to dampen growth performance. Oil dependence is also a significant concern as oil production is on a declining trend. According to the IMF, Syria will become a net oil importer within four to six years, with oil supplies likely to be exhausted in a couple of decades. -

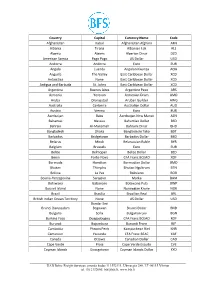

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________