The Roots and Gadgets of Pop Culture in the Late 20Th Century Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2010, Ray Lowry @ Idea Generation Gallery 0

(http://whitehotmagazine.com/) ADVERTISE (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/DOCUMENTS/ADVERTISE) RECENT (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/NEW) CITIES (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM//CITIES) CONTACT (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/DOCUMENTS/CONTACT) ABOUT (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/DOCUMENTS/ABOUT) OPENINGS LISTINGS (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/POSTINGS) JANUARY 2017 - "THE BEST ART IN THE WORLD" July 2010, Ray Lowry @ Idea Generation Gallery 0 "London Calling" reinterpreted by Tracy Emin, 2010 Photo: Chris Osburn Ray Lowry: London Calling Idea Generation Gallery (http://www.ideageneration.co.uk/generationgallery.php) 11 Chance Street London, E2 7JB June 18th through July 4th, 2010 Ray Lowry: London Calling at the Idea Generation Gallery in East London pays tribute to Ray Lowry's iconic cover art for The Clash's 1979 album, London Calling. For the show, thirty prominent artists contributed their interpretations of Lowry's seminal album cover. In addition to the artists' takes on Lowry's cover, they were invited to have a look at how he and his ideologies had influenced them. Alongside these works, original sketches, designs for the album cover as well as private sketchbooks, personal letters, previously unseen photographs and painting are on show. Originally from Manchester, Ray Lowry started his career as an artist drawing for Punch Magazine, International Times and Private Eye. His association with the music press began in the 70s, most notably with NME for which he created a variety of cartoons and illustrations. He met The Clash at Manchester's Electric Circus where they were the supporting act for the Sex Pistols during raucous the Anarchy in the UK tour. A friendship between Lowry and The Clash ensued, and he was invited to accompany them on their 1979 US tour as the band's “official war artist”. -

Courses Everywhere Have One Thing in Common Aide Par 2020 • Wherever Golf Is Played Is Golf Wherever of EXC RS EL a L E E Y N C 5 E 6

2020 CATALOG Courses everywhere have one thing in common in thing one have 2020 Par Aide • Wherever Golf is Played OF EXC RS EL A L E E Y N C 5 E 6 W H D E E Y R A E L V E P R G O L F IS Products and partnerships, built without compromise. For 65 years, Par Aide has been the industry’s premier partner for advanced turf maintenance tools, innovative course products and essential accessories, used at leading golf facilities worldwide. Our products are thoughtfully designed to help protect your course health, reduce maintenance requirements and costs, and provide the very best experience to your golfers — inspiring high customer satisfaction and return visits that help drive course revenue. Proven Par Aide solutions help deliver superior conditions and labor-saving productivity. With industry-leading design and functionality, and long-lasting durability that extends the life of your investment. Our products are known throughout the industry for innovation, unsurpassed quality and superior lifetime value. Courses everywhere have one thing in common — Par Aide, the iconic name in golf course accessories. On behalf of all of us at Par Aide, I would like to thank you for an incredible 65 years! Our industry is built on relationships. This was true 65 years ago when my father started Par Aide and it holds true today. We greatly value our relationship with you. You've helped make Par Aide the company that it is today. We look forward to the next 65 years with you all. Steve Garske, Chief Executive Officer TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 TEE PRODUCTS ECO-ENCLOSURES -

Ian Siegal Wire the Crazy World of Arthur Brown

OCTOBER 2013 SEPTEMBER 2013 LIVE IN LEICESTER PRESENTS... MAGIC TEAPOT PRESENTS... FRI 4 TUE 3 THE CRAZY WORLD OF ARTHUR BROWN JOHN MURRY £16adv - plus support £10adv - plus Liam Dullaghan The source of Arthur Brown’s music lies beyond both the spiritual Hailing from Tupelo, Mississippi; John Murry’s solo debut album and the material. His first album The Crazy World of Arthur Brown ‘The Graceless Age’ is imbued with the ghosts of the Southern was his theatrical statement of this. It, and the single Fire! - which states and the personal demons that have haunted him throughout came from it - were both a hit on the two sides of the Atlantic. his life. He has described himself as more absorbed in the world He is a performance artist who also became a rock icon and his of literature than in the day-to-day concerns of the modern world, influence was felt through his theatrical musical style, his theatrical and for good reason: he’s second cousin to William Faulkner and presentation, his dancing, and his vocal ability. His voice has been has spent much time with his second cousin’s work. Throughout described as “one of the most beautiful voices in rock music” and his songs in the key of heartbreak, there is nonetheless a strong his presentation is second to none! Recently he won Classic Rock’s and abiding sense of salvation and reconciliation. Showman of the Year Award. www.arthur-brown.com www.johnmurry.com TUE 15 XANDER PROMOTIONS PRESENTS... ROACHFORD THU 12 £12adv £14door KATHRYN WILLIAMS Ever since bulldozing his way onto the scene with unforgettable £12adv £14door - plus Alex Cornish tracks like ‘Cuddly Toy’ and ‘Family Man’ in the late 80s, Andrew Kathryn Williams’ artful and soulful compositions and sweet Roachford’s maverick take on music has spread far and wide. -

PUNK GRAPHICS. Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die

PUNK GRAPHICS. Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die PEDAGOGISCH DOSSIER INTRODUCTION 2 HELPFUL HINTS FOR YOUR VISIT & CONTENT OF THE KIT 3 1. COPY AND PASTE: THE APPROPRIATED IMAGE 4 2. CUT ‘N’ PASTE: COLLAGE & BRICOLAGE 6 3. RIDING A NEW WAVE 8 4. ECCENTRIC ALPHABETS: PUNK TYPOGRAPHY 9 5. COMIC RELIEF 11 6. SCARY MONSTERS & SUPER CREEPS 12 7. DO IT YOURSELF: ZINES & FLYERS 13 8. FOR ART’S SAKE 17 9. BACK TO THE FUTURE: RETRO GRAPHICS 20 10. AGIT-PROP: POWER TO THE PEOPLE 21 11. BELGIUM AIN’T FUN NO MORE 23 GLOSSARY 24 CREDITS 25 INFORMATION AND RESERVATION 26 PUNK GRAPHICS. Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die - Educational kit 1 INTRODUCTION More than forty years after punk exploded onto the music scenes of New York and London, its impact on the larger culture is still being felt. Born in a period of economic malaise, punk was a reaction, in part, to an increasingly formulaic rock music industry. Punk’s energy coalesced into a powerful subcultural phenomenon that transcended music to affect other fields, such as visual art, fashion, and graphic design. This exhibition explores the unique visual language of punk as it evolved in the United States and the United Kingdom through hundreds of its most memorable graphics—flyers, posters, albums, promotions, and zines. Drawn predominantly from the extensive collection of Andrew Krivine, PUNK GRAPHICS reveals punk as a range of diverse approaches and eclectic styles that resists its reduc- tion to just a handful of stereotypes. The Belgian appendix shows how these approaches and styles also inspired continental punk design. -

Nero Numero 0

questo primo numero è dedicato a Emiliana Mensile a distribuzione gratuita Direttore Responsabile Giuseppe Mohrhoff 02 / RUSS MEYER Direzione 05 / ANOMOLO RECORDS Francesco de Figueiredo 08 / MELTING & DISTINGUISHING ([email protected]) Luca Lo Pinto 10 / CONTEMP/OLACCHI ([email protected]) Valerio Mannucci 12 / RAYMOND SCOTT ([email protected]) Lorenzo Micheli Gigotti 15 / PARIS-DABAR ([email protected]) 16 / OLAF NICOLAI Collaboratori 19 / ENDOGONIDIA Francesco Tato’ 23 / CESARE PIETROIUSTI / Rosso Ilaria Gianni Rudi Borsella 27 / WAKING LIFE Francesco Ventrella Carola Bonfili 30 / ACCUMULAZIONI > DISPERSIONI Anna Passarini Edoardo Caruso 32 / JUSTIN BENNETT Paolo Colasacco Nicola Capodanno 35 / ARCHIGRAM Andrea Proia Anna Neudecker 37 / WIRE Marco Cirese Marta Garzetti 40 / TORE SANSONETTI Edgardo Ferrati 42 / NERO TAPES Progetto Grafico e Impaginazione Industrie Grafiche di Roma 43 / RICCARDO PREVIDI / Supercolosseo 2004 Daniele De Santis ([email protected]) 44 / RECENSIONI Pubblicita’ 48 / NERO INDEX [email protected] 06/97600104 339/7825906 339/1453359 Distribuzione [email protected] 333/6628117 333/2473090 Editore Produzioni NERO soc. coop. a r.l NERO Numero 1 Via Paolo V, 53 00168 ROMA tel. 06/97600104 - [email protected] www.neromagazine.it registrazione al tribunale di Roma n. 102/04 del 15 marzo 2004 Stampa OK PRINT Via Calamatta, 16 - ROMA In copertina un’illustrazione di Carola Bonfili ogni erotomane assillato dall’abbondanza godereccia e sbavona dei seni gonfi, grossi e fecondi. Erotismo e violenza, spirito di sopraffazione tra sessi e ironia, prorompenti pin-up e reietti sociali sono miscelati all’interno di vicende narrative sconclusionate e RUSS MEYER demenziali. di Lorenzo Micheli Gigotti Quello di Russ Meyer è uno sguardo provocatorio “Signori e signore benvenuti alla violenza. -

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Punk-rock (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") London's burning TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The effervescence of New York's underground scene was contagious and spread to England with a 1976 tour of the Ramones that was artfully manipulated to start a fad (after the "100 Club Festival" of september 1976 that turned British punk-rock into a national phenomenon). In the USA the punk subculture was a combination of subterranean record industry and of teenage angst. In Britain it became a combination of fashion and of unemployment. Music in London had been a component of fashion since the times of the Swinging London (read: Rolling Stones). Punk-rock was first and foremost a fad that took over the Kingdom by storm. However, the social component was even stronger than in the USA: it was not only a generic malaise, it was a specific catastrophe. The iron rule of prime minister Margaret Thatcher had salvaged Britain from sliding into the Third World, but had caused devastation in the social fabric of the industrial cities, where unemployment and poverty reached unprecedented levels and racial tensions were brooding. -

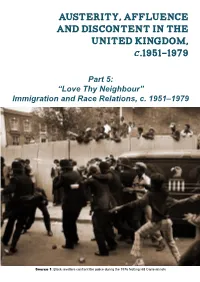

Austerity, Affluence and Discontent in the United Kingdom, .1951-1979

AUSTERITY, AFFLUENCE AND DISCONTENT IN THE UNITED KINGDOM, .1951-1979 Part 5: “Love Thy Neighbour” Immigration and Race Relations, c. 1951–1979 Source 1: Black revellers confront the police during the 1976 Notting Hill Carnival riots 2 Austerity, Affluence and Discontent in the United Kingdom, c.1951–1979: Part 5 Introduction Before the Second World War there were very few non-white people living permanently in the UK, but there were 2 million by 1971. Two thirds of them had come from the Commonwealth countries of the West Indies, India, Pakistan and Hong Kong, but one third had been born in the UK. The Commonwealth was the name given to the countries of the British Empire. However, as more and more countries became independent from the UK, the Commonwealth came to mean countries that had once been part of the Empire. Immigration was not new. By the 1940s there were already black communities in port cities like Bootle in Liverpool and Tiger Bay in Cardiff. Groups of Chinese people had come to live in the UK at the end of the 19th century and had settled in Limehouse in London, and in the Chinatown in Liverpool. Black West Indians had come to the UK to fight in the Second World War. The RAF had Jamaica and Trinidad squadrons and the Army had a West Indian regiment. As a result there were 30,000 non-white people in the UK by the end of the war.1 The British people had also been very welcoming to the 130,000 African-American troops of the US Army stationed in the UK during the war. -

Sale Name: Burnt Block Vrh Agreement No: 30-97513

TIMBER NOTICE OF SALE SALE NAME: BURNT BLOCK VRH AGREEMENT NO: 30-97513 AUCTION: April 24, 2019 starting at 10:00 a.m., COUNTY: Clallam Olympic Region Office, Forks, WA SALE LOCATION: Sale located approximately 8 miles south of Sequim, WA PRODUCTS SOLD AND SALE AREA: All timber, except trees marked with a ring of blue paint or bounded out by leave tree area tags, all downed red cedar, and all timber that has been on the ground for five years or more; bounded by timber sale boundary tags, pink flag lines, timber type change and the PT-J-2700 road in Unit 1; bounded by sale boundary tags, timber type change in Units 2 & 3; all timber bounded by right of way tags on part(s) of Sections 7, 17 and 18 all in Township 29 North, Range 3 West, W.M., containing 105 acres, more or less. CERTIFICATION: This sale is certified under the Sustainable Forestry Initiative® program Standard (cert no: PwC-SFIFM-513) ESTIMATED SALE VOLUMES AND QUALITY: Avg Ring Total MBF by Grade Species DBH Count MBF 1P 2P 3P SM 1S 2S 3S 4S UT Douglas fir 19.9 8 3,923 2,311 1,409 191 13 Hemlock 12.2 159 20 105 34 Red cedar 12.9 92 60 32 Silver fir 20.4 39 30 9 Grand fir 20 20 14 5 1 Maple 12 6 4 2 Sale Total 4,239 MINIMUM BID: $839,000.00 BID METHOD: Sealed Bids PERFORMANCE SECURITY: $100,000.00 SALE TYPE: Lump Sum EXPIRATION DATE: October 31, 2020 ALLOCATION: Export Restricted BID DEPOSIT: $83,900.00 or Bid Bond. -

New Singles, 26

INSIDE *'*$.'_■ ... Amm L --- *#&&&* Singles chart, 10-11; Album chart,New Albums, 25; New 8; AirplaySingles, guide, 26; lands18-19; special, Small Labels,16-24. 13; Mid- March 9, 1981 VOLUME THREE Number 49 Major TV push for Televideo... THE MOST ambitious attempt so far to able for rental and UA repertoire is directions. There will, however, be a equipmentmass merchandise through videodirect-response software andTV excludedThe first from 90-seconds being sold. commercials will coveringspecial no-deposit any film in introductory the UA catalogue offer donadvertising area. begins tonight in the Lon- Thamesbe screened TV and Monday-Thursdays the campaign will runon andfor a feepacking. of £5.95 The plus concessionary 95p return postage rate existingThe twoTellydisc major directparticipants mail inrecord the areafor two response weeks. furtherDepending regional on London- promo- freenegotiated hire for with an annual Granada payment gives six and weeks two companycompany, BertlesmannEurodisc, and through the Huttonits UK committedtion is envisaged to further and TV Televideoupdates dur- is weeksOn foraverage, monthly Televideo's payments. purchase joinedadvertising forces agencythis time have with oncethe Intervi- again specialing the offers,year to likepromote blank new tapes releases and video and pricepercent on belowsoftware retail. are claimed to be 25 sionSelwood, company, former to Pyeform and Televideo. CBS market- Clive Because of the relatively complex entertainment."We are in theThere business will be of no family soft HEATH LEVY Music continues to ing director,director. has been appointed manag- club,nature the of focusenrolling of the in TVthe advertisingTelevideo companyporn in our spokesman. catalogue," "Our commented research a tion'mop list. -

Trouser Press

ARTIST TITLE SECTION ISSUE Dick Wagner incl (guitarists) 35 Richard Wagner Hit and Run 35 Wah! Nah Poo the Art of Bluff 69 Green Circles 84, 88 Wah! Heat Green Circles 61 John Waite Ignition Hit and Run 77 Waitresses article 73 incl 41 Fax n Rumours 90 Wasn’t Tomorrow Wonderful? 72 Bruiseology 87 America Underground 30 Rick Wakeman article 20 Rhapsodies Hit and Run 42 1984 Hit and Run 66 T. Bone Walker Singing the Blues 1 Scott Walker Fire Escape in the Sky Hit and Run 69 Walker Brothers Nite Flights 34 Wall Green Circles 48 Larry Wallis Green Circles 26 See also Pink Fairies Wall of Voodoo article 81, 87 Dark Continent Hit and Run 69 Call of the West Hit and Run 80 Green Circles 60 Joe Walsh incl (guitarists) 35 The Best of Joe Walsh Hit and Run 35 There Goes the Neighborhood Hit and Run 65 Steve Walsh Schemer-Dreamer Hit and Run 48 Wang Chung Points on the Curve Hit and Run 96 Ward 8 America Underground 96 Steve Warley Steve Warley Hit and Run 81 Warm Jets Green Circles 48 Paul Warren and the One of the Kids Hit and Run 55 Explorers Warsaw Pakt Fax n Rumours 26 Jeff Waryan Figures 94 Washington DC scene America Underground 26, 42, 80, 84, 95 :30 Over DC (Limp) America Underground 39 Was (Not Was) Was (Not Was) 68 Born to Laugh at Tornadoes 94 Green Circles 73 Water Pistols Green Circles 19 Muddy Waters / Howlin’ Wolf Muddy and the Wolf 82 Geraint Watkins Geraint Watkins and the Dominators 43 Green Circles 57 Kit Watkins Frames of Mind Hit and Run 85 Gerald Watkiss Purgatory and Paradise Hit and Run 32 Ben Watt and Robert Wyatt Green -

The Specials First Album

1 / 2 The Specials First Album 40 Years after The Specials first burst on to the scene with their own brand of ska, reggae and rude boy style, are truly back at the top with .... ' The next single, 'A Message To You Rudy', followed in September with their first album released soon after in October. This 40th Anniversary Edition of their .... The Specials debut features a mix of re-workings of songs by Prince Buster, Toots Hibbert as well as Dandy Livingstone's 'Rudy, A Message to .... I learned to play all the lines of their first album, one by one, then I started to dig in the ska music deeper and deeper. When we started our band .... After the fabulous debut album The Specials, The Specials went to work on album number two. It would be the last album made by the original .... Ska legends The Specials released just two albums before they split up in 1981, but are now enjoying chart-topping success. This 40th Anniversary 8-CD Collection contains the first 8 albums released on the label, with offerings by The Specials, The Selecter and Rico, along with the .... The Specials' classic Elvis Costello-produced 1979 debut album was the subject of a Tim's Twitter Listening Party on Sunday, featuring .... Late in 1979, the band released its landmark debut album, The Specials, produced by Elvis Costello. They followed with several 2-Tone package tours and a .... Beginning with "Guns of Navarone," adopted from ska progenitors the Skatalites, the band proceeded to play over half of the first album to ecstatic ... -

The Guardian, Week of August 3, 2020

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 8-3-2020 The Guardian, Week of August 3, 2020 Wright State Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State Student Body (2020). The Guardian, Week of August 3, 2020. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Retro Rewind: “London Calling” by The Clash Maxwell Patton August 3, 2020 Rock music in its various styles would in no way, shape, or form be what it is today without the influence of a certain British punk icon known as The Clash. Even though the band lays claim to one of the shortest lifespans in my Retro Rewind reviews (being active for only a decade), they have had a massive amount of influence on the rock realm with their distinctly political lyrics and driving, guitar-centered instrumentals. Their third record, by far their most popular, is the subject of my review today: the 1979 double album “London Calling,” which is viewed by many as a definitive album in the punk genre. Released on Dec. 14, 1979, the record contains 19 songs of varying styles and was supported by three singles: the title track “London Calling,” “Clampdown,” and “Train in Vain (Stand by Me).” The themes delved into throughout the album include unemployment, the usage of drugs, paranoia, and depression.