Shannon Buckner 10Pipe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

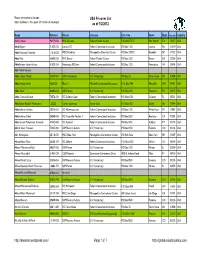

USA Prisoner List As of 1/2/2012 Page

Please remember to include USA Prisoner List return address in the upper left corner of envelope as of 1/2/2012 Name Number Prison Line one Line Two Town State Postcode Country Aafia Siddiqui 90279-054 FMC Carswell Federal Medical Center P.O. Box 27137 Fort Worth TX 76127 USA Abad Elfgeeh 31523-053 Loretto FCI Federal Correction Institution PO Box 1000 Loretto PA 15940 USA Abdel Hameed Shehadeh 11815-022 MDC Brooklyn Metropolitan Detention Center PO Box 329002 Brooklyn NY 11232 USA Abdel Nur 64655-053 FMC Butner Federal Medical Center PO Box 1600 Butner NC 27509 USA Abdelhaleem Hasan Ashqar 41500-054 Petersburg FCI Low Federal Correction Institution PO Box 1000 Petersburg VA 23804 USA Abdi Mahdi Hussein Abdul Hakim Murad 37437-054 USP Terre Haute U.S. Penitentiary PO Box 33 Terre Haute IN 47808 USA Abdul Hamin Awkal A267328 Man CI Mansfield Correctional Institution P. O. Box 788 Mansfield OH 44901 USA Abdul Kadir 64656-053 USP Canaan U.S. Penitentiary P.O. Box 300 Waymart PA 18472 USA Abdul Tawala Alishtari 70276-054 FCI Coleman Low Federal Correctional Institution P.O. Box 1031 Coleman FL 33521 USA Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad 150550 Varner Supermax Varner Unit P.O. Box 400 Grady AR 71644 USA Abdulrahman Farhane 58376-054 FCI Allenwood Low Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 1000 White Deer PA 17887 USA Abdulrahman Odeh 26548-050 FCI Victorville Medium II Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 5300 Adelanto CA 92301 USA Abdurahman Muhammad Alamoudi 47042-083 FCI Ashland Federal Correction Institution PO Box 6001 Ashland KY 41105 USA Adham Amin Hassoun 72433-004 USP Florence Admax U.S. -

Aafia Siddiqui #90279-054 FMC Carswell Federal Medical Center

Aafia Siddiqui #90279-054 Abad Elfgeeh #31523-053 Abdel Hameed Shehadeh #11815-022 FMC Carswell Loretto FCI MDC Brooklyn Federal Medical Center Federal Correctional Institution Metropolitan Detention Center P.O. Box 27137 PO Box 1000 PO Box 329002 Fort Worth, TX 76127 Loretto, PA 15940 Brooklyn, NY 11232 USA USA USA Abdel Nur #64655-053 Abdelhaleem Hasan Ashqar #41500-054 Abdul Hakim Murad #37437-054 FMC Butner Petersburg FCI Low FCI Terre Haute Federal Medical Center Federal Correctional Institution Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 1600 PO Box 1000 PO Box 33 Butner, NC 27509 Petersburg, VA 23804 Terre Haute, IN 47808 USA USA USA Abdul Hamin Awkal #A267328 Abdul Kadir #64656-053 Abdul Tawala Alishtari #70276-054 Man CI USP Canaan FCI Coleman Low Mansfield Correctional Institution U.S. Penitentiary Federal Correctional Institution P. O. Box 788 P.O. Box 300 P.O. Box 1031 Mansfield, OH 44901 Waymart, PA 18472 Coleman, FL 33521 USA USA USA Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad #150550 Abdulrahman Farhane #58376-054 Abdulrahman Odeh #26548-050 Varner Supermax FCI Allenwood Low FCI Victorville Medium II Varner Unit Federal Correctional Institution Federal Correctional Institution P.O. Box 400 PO Box 1000 PO Box 5300 Grady, AR 71644 White Deer, PA 17887 Adelanto, CA 92301 USA USA USA Abdurahman Muhammad Alamoudi #47042-083 Adham Amin Hassoun #72433-004 Adis Medunjanin #65114-053 FCI Ashland USP Florence Admax MCC New York Federal Correctional Institution U.S. Penitentiary Metropolitan Correctional Center PO Box 6001 PO Box 8500 150 Park Row Ashland, KY 41105 Florence, CO 81226 New York, NY 10007 USA USA USA Adnan Babar Mirza #66255-179 Ahmad Mohammad Ajaj #40637-053 Ahmed Abdel Sattar #53506-054 FCI Safford USP Florence Admax USP Florence Admax Federal Correctional Institution U.S. -

SIGINT for Anyone

THE ORIGINS OF AMERICA’S JIHADISTS THE ORIGINS OF AMERICA’S About This Perspective The U.S. homeland faces a multilayered threat from terrorist organizations. Homegrown jihadists account for most of the terrorist activity in the United States since 9/11. Efforts by jihadist terrorist organizations to inspire terrorist attacks in the United States have thus far yielded meager results. No American jihadist group has emerged to sustain a terrorist campaign, and there is no evidence of an active jihadist underground to support a continuing terrorist holy war. The United States has invested significant resources in THE ORIGINS OF preventing terrorist attacks, and authorities have been able to uncover and thwart most of the terrorist plots. This Perspective identifies 86 plots to carry out terrorist attacks and 22 actual attacks since 9/11 involving 178 planners and perpetrators. Eighty-seven percent of those planners and perpetrators had long residencies in the United States. Only four of them had come to the United States illegally, all as minors. Nationality is a poor predictor of later terrorist activity, and vetting people coming to the United States, no matter how rigorous, cannot identify those who radicalize here. Determining whether a young teenager might, more than 12 years later, turn out to be a jihadist AMERICA’S terrorist would require the bureaucratic equivalent of divine foresight. Jenkins JIHADISTS Brian Michael Jenkins $21.00 ISBN-10 0-8330-9949-3 ISBN-13 978-0-8330-9949-5 52100 C O R P O R A T I O N www.rand.org Perspective EXPERT INSIGHTS ON A TIMELY POLICY ISSUE C O R P O R A T I O N 9 780833 099495 R PE-251-RC (2017) barcode_template_CC15.indd 1 10/17/17 12:00 PM Contents Summary of Key Judgments ..................................................................................1 The Origins of America’s Jihadists .........................................................................3 Appendix ............................................................................................................. -

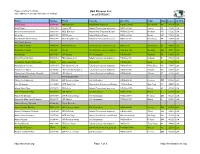

USA Prisoner List As of 5/13/2012 Page 1 of 9 Http

Please remember to include USA Prisoner List return address in the upper left corner of envelope as of 5/13/2012 Name Number Prison Line one Line Two Town State Postcode Country Aafia Siddiqui 90279-054 FMC Carswell Federal Medical Center P.O. Box 27137 Fort Worth TX 76127 USA Abad Elfgeeh 31523-053 Loretto FCI Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 1000 Loretto PA 15940 USA Abdel Hameed Shehadeh 11815-022 MDC Brooklyn Metropolitan Detention Center PO Box 329002 Brooklyn NY 11232 USA Abdel Nur 64655-053 FMC Butner Federal Medical Center PO Box 1600 Butner NC 27509 USA Abdelhaleem Hasan Ashqar 41500-054 Petersburg FCI Low Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 1000 Petersburg VA 23804 USA Abdi Mahdi Hussein Abdul Hakim Murad 37437-054 FCI Terre Haute Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 33 Terre Haute IN 47808 USA Abdul Hamin Awkal A267328 Man CI Mansfield Correctional Institution P. O. Box 788 Mansfield OH 44901 USA Abdul Kadir 64656-053 USP Canaan U.S. Penitentiary P.O. Box 300 Waymart PA 18472 USA Abdul Tawala Alishtari 70276-054 FCI Coleman Low Federal Correctional Institution P.O. Box 1031 Coleman FL 33521 USA Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad 150550 Varner Supermax Varner Unit P.O. Box 400 Grady AR 71644 USA Abdulrahman Farhane 58376-054 FCI Allenwood Low Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 1000 White Deer PA 17887 USA Abdulrahman Odeh 26548-050 FCI Victorville Medium II Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 5300 Adelanto CA 92301 USA Abdurahman Muhammad Alamoudi 47042-083 FCI Ashland Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 6001 Ashland KY 41105 USA Adel Abdul Bary Awaiting Extradition Adham Amin Hassoun 72433-004 USP Florence Admax U.S. -

The American Terrorist

Terry Oroszi, EdD Boonshoft School of Medicine, WSU Intelligence Analysis Career Training Program, WSARC The Dayton Think Tank, Dayton, OH Briefing: This research identifies the attributes of an American terrorist by studying the patterns within 34 demographic variables and exploring their correlation with the motivation to commit crimes related to terrorism. We believe that such an understanding will help to halt the recruitment of American citizens by instructing concerned parents, coaches, teachers, and family members how to quickly identify a person that is susceptible to radicalization and how to intervene. Studies conducted 20 years ago have identified some markers by examining international terrorists: single, male, early 20’s, university education, and from an affluent middle or upper-class family (Russell, 1977; Jenkins, 1980, Dingley, 1997). This study confirms the previous findings and expands upon them by examining 519 U.S. citizens convicted of crimes related to terrorism. Additional characteristics scrutinized include the location of residence, crime and imprisonment, religion, organizational alliances, race, heritage and path to citizenship, field of study and occupation, social status, military experience, mental health, marriage and family, conviction, punishment, and target. We endeavor to continue identifying the common traits of terrorists and the social circumstances that render a person susceptible to radicalization and prime them to commit acts of terrorism. By creating a well-sourced and researched list of behaviors we offer methods for community-based curbing of radicalization. Briefing: This research identifies the attributes of an American terrorist by studying the patterns within 34 demographic variables and exploring their correlation with the motivation to commit crimes related to terrorism. -

Estimating the Prevalence of Entrapment in Post-9/11 Terrorism Cases, 105 J

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 105 | Issue 3 Article 2 Summer 2015 Estimating the Prevalence of Entrapment in Post-9/ 11 Terrorism Cases Jesse J. Norris Hanna Grol-Prokopczyk Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Jesse J. Norris and Hanna Grol-Prokopczyk, Estimating the Prevalence of Entrapment in Post-9/11 Terrorism Cases, 105 J. Crim. L. & Criminology (2015). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol105/iss3/2 This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. 2. NORRIS FINAL FOR PRINTER (CORRECTED OCT. 11) 10/11/2016 9:14 AM 0091-4169/15/10503-0609 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 105, No. 3 Copyright © 2016 by Jesse J. Norris and Hanna Grol-Prokopczyk Printed in U.S.A. ESTIMATING THE PREVALENCE OF ENTRAPMENT IN POST-9/11 TERRORISM CASES JESSE J. NORRIS* & HANNA GROL-PROKOPCZYK** [T]he essence of what occurred here is that a government . came upon a man both bigoted and suggestible, one who was incapable of committing an act of terrorism on his own, created acts of terrorism out of his fantasies of bravado and bigotry, and made those fantasies come true. [R]eal terrorists would not have bothered themselves with a person who was so utterly inept. -

The American Terrorist: Everything You Need to Know to Be a Subject Matter Expert

THE AMERICAN TERRORIST: EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW TO BE A SUBJECT MATTER EXPERT Terry Oroszi, EdD Intel Analysis Program, WSARC Boonshoft School of Medicine, WSU The Dayton Think Tank, Dayton, OH Briefing: This research identifies the attributes of an American terrorist by studying the patterns within 34 demographic variables and exploring their correlation with the motivation to commit crimes related to terrorism. We believe that such an understanding will help to halt the recruitment of American citizens by instructing concerned parents, coaches, teachers, and family members how to quickly identify a person that is susceptible to radicalization and how to intervene. Studies conducted 20 years ago have identified some markers by examining international terrorists: single, male, early 20’s, university education, and from an affluent middle or upper- class family (Russell, 1977; Jenkins, 1980, Dingley, 1997). This study confirms the previous findings and expands upon them by examining 519 U.S. citizens convicted of crimes related to terrorism. Additional characteristics scrutinized include the location of residence, crime and imprisonment, religion, organizational alliances, race, heritage and path to citizenship, field of study and occupation, social status, military experience, mental health, marriage and family, conviction, punishment, and target. We endeavor to continue identifying the common traits of terrorists and the social circumstances that render a person susceptible to radicalization and prime them to commit acts of terrorism. By creating a well-sourced and researched list of behaviors we offer methods for community-based curbing of radicalization. Briefing: This research identifies the attributes of an American terrorist by studying the patterns within 34 demographic variables and exploring their correlation with the motivation to commit crimes related to terrorism. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 113 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 159 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 5, 2013 No. 78 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was tions in the garment industry there. Listen to what the women told me: called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Bangladesh is the second largest gar- Rehana jumped from the fourth floor pore (Mr. STEWART). ment-producing nation, employing window and was knocked unconscious. f over 4 million skilled and industrious She broke her leg, and the doctors told workers, mostly women, at a minimum her she will need to be on crutches for DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO wage of $37 a month. I learned that the rest of her life. TEMPORE many factories have continued to oper- Reba was the breadwinner in her The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- ate in unsafe residential or multistory home. She jumped from the third floor. fore the House the following commu- commercial buildings even after the She cannot work because of the pain. nication from the Speaker: Rana Plaza collapse. I learned more Her husband is sick. She has two sons, WASHINGTON, DC, about poor conditions created by a one of whom just qualified for the mili- June 5, 2013. myriad of middlemen hired by retailers tary college, but she doesn’t know if I hereby appoint the Honorable CHRIS that pit one factory against the next, she can afford to keep him there; and STEWART to act as Speaker pro tempore on squeezing out the last few pennies per until I prodded Bangladesh Garment this day. -

Aafia Siddiqui #90279-054 FMC Carswell Federal Medical Center

Aafia Siddiqui #90279-054 Abad Elfgeeh #31523-053 Abdel Hameed Shehadeh #11815-022 FMC Carswell Loretto FCI MDC Brooklyn Federal Medical Center Federal Correctional Institution Metropolitan Detention Center P.O. Box 27137 PO Box 1000 PO Box 329002 Fort Worth, TX 76127 Loretto, PA 15940 Brooklyn, NY 11232 USA USA USA Abdel Nur #64655-053 Abdelhaleem Hasan Ashqar #41500-054 Abdul Hakim Murad #37437-054 MDC Brooklyn Petersburg FCI Low USP Florence Admax Metropolitan Detention Center Federal Correctional Institution U.S. Penitentiary PO Box 329002 PO Box 1000 PO Box 8500 Brooklyn, NY 11232 Petersburg, VA 23804 Florence, CO 81226 USA USA USA Abdul Hamin Awkal #A267328 Abdul Kadir #64656-053 Abdul Tawala Alishtari #70276-054 Man CI MDC Brooklyn FCI Coleman Low Mansfield Correctional Institution Metropolitan Detention Center Federal Correctional Institution P. O. Box 788 PO Box 329002 P.O. Box 1031 Mansfield, OH 44901 Brooklyn, NY 11232 Coleman, FL 33521 USA USA USA Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad #150550 Abdulrahman Farhane #58376-054 Abdulrahman Odeh #26548-050 Varner Supermax FCI Allenwood Low FCI Victorville Medium II Varner Unit Federal Correctional Institution Federal Correctional Institution P.O. Box 400 PO Box 1000 PO Box 5300 Grady, AR 71644 White Deer, PA 17887 Adelanto, CA 92301 USA USA USA Abdulwali Abdukhad Muse #70636-054 Abdurahman Muhammad Alamoudi #47042-083 Adel Abdul Bary #67496-054 MCC New York FCI Terre Haute MCC New York Metropolitan Correctional Center Federal Correctional Institution Metropolitan Correctional Center 150 Park -

Police Gen KMBH-554E-20160314144619

UNCLASSIF1ED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Intelligence Assessment (U//FOUO) Decade in Review: Self-Selecting US Persons Drive Post-2006 Increase in Anti-US Plotting 7 March 2011 UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY 304 UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY (U) Executive Summary (U//FOUO) Analysis of all plots3 against the United States and US interests between 2001 and 2010 by action-oriented indicted Islamic extremistsb indicated there was an 11 percent increase in the number of incidents after 2006 as compared to the earlier half of the decade. The FBI and the Joint Regional Intelligence Center (JRIC) assess with high confidence,c based on available and reliable open source reporting, that US person activity drove the post-2006 rise, as the group was five times more active than foreign nationals in the same timeframe. (U//FOUO) The FBI and the JRIC assess with high confidence, based on available and reliable open source reporting, that several events that emerged during the decade may have triggered growing numbers of action-oriented indicted Islamic extremists to devise and sometimes execute their plans. These events included, but were not limited to, a broadening US military presence overseas and outreach by lslamist ideologues, especially those with specific appeal to English speakers. In addition to individually specific triggers, infonnation from the dataset appeared to indicate much of the activity stemmed from a perception that the United States is at war with Islam and jihad is the correct and obligatory response. (U//FOUO) Analysis of the dataset showed that as activity by US persons rose, activity by foreign nationals dropped. -

Jihad on Main Street: Explaining the Threat of Jihadist Terrorism to the American Homeland Since 9/11

Jihad on Main Street: Explaining the Threat of Jihadist Terrorism to the American Homeland Since 9/11 ASHLEY LOHMANN MAY 18, 2010 DR. MARTHA CRENSHAW, ADVISOR HONORS PROGRAM FOR INTERNATIONAL SECURITY STUDIES CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL SECURITY AND COOPERATION STANFORD UNIVERSITY This research was supported by the United States Department of Homeland Security through the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), grant number 2008ST061ST0004. However, any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect views of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. ii Abstract Since September 11, 2001, 26 jihadist plots and attacks have targeted the American homeland, but because the details of the plots and attacks as well as the profiles of their perpetrators vary greatly, scholars, government officials, and other authorities still disagree about the seriousness of threat posed by jihadist terrorism to the United States. This study provides a clearer understanding of the nature of jihadist terrorism in the US by examining all 26 plots and attacks in detail. It concludes that jihadist terrorism is generally a minimally-threatening, homegrown phenomenon, but some plots and attacks still emerge that do pose a serious threat to US national security. Of the 26 plots and attacks since 9/11, seven can be considered “serious,” and the emergence of these plots and attacks can best be explained by examining those using explosive devices separately from those using firearms. Regarding the first category, Western jihadists’ contacts with veteran jihadist organizations (such as al-Qaeda) and access to training camps explain the ability of some to construct serious bombing plots. -

USA List of Prisoners Mailing Labels Avery 5160

Aafia Siddiqui #90279-054 Abad Elfgeeh #31523-053 Abdel Hameed Shehadeh #11815-022 FMC Carswell Loretto FCI MDC Brooklyn Federal Medical Center Federal Correctional Institution Metropolitan Detention Center P.O. Box 27137 PO Box 1000 PO Box 329002 Fort Worth, TX 76127 Loretto, PA 15940 Brooklyn, NY 11232 USA USA USA Abdel Nur #64655-053 Abdelhaleem Hasan Ashqar #41500-054 Abdul Hakim Murad #37437-054 FMC Butner Petersburg FCI Low FCI Terre Haute Federal Medical Center Federal Correctional Institution Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 1600 PO Box 1000 PO Box 33 Butner, NC 27509 Petersburg, VA 23804 Terre Haute, IN 47808 USA USA USA Abdul Hamin Awkal #A267328 Abdul Kadir #64656-053 Abdul Tawala Alishtari #70276-054 Man CI USP Canaan FCI Coleman Low Mansfield Correctional Institution U.S. Penitentiary Federal Correctional Institution P. O. Box 788 P.O. Box 300 P.O. Box 1031 Mansfield, OH 44901 Waymart, PA 18472 Coleman, FL 33521 USA USA USA Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad #150550 Abdulrahman Farhane #58376-054 Abdulrahman Odeh #26548-050 Varner Supermax FCI Allenwood Low FCI Oxford Varner Unit Federal Correctional Institution Federal Correctional Institution P.O. Box 400 PO Box 1000 PO Box 1000 Grady, AR 71644 White Deer, PA 17887 Oxford, WI 53952 USA USA USA Abdulwali Abdukhad Muse #70636-054 Abdurahman Muhammad Alamoudi #47042-083 Adel Abdul Bary #67496-054 FCI Terre Haute Ashland FCI MCC New York Federal Correctional Institution Federal Correctional Institution Metropolitan Correctional Center PO Box 33 PO Box 6001 150 Park Row Terre Haute, IN 47808 Ashland, KY 41105 New York, NY 10007 USA USA USA Adham Amin Hassoun #72433-004 Adis Medunjanin #65114-053 Adnan Babar Mirza #66255-179 USP Florence Admax USP Florence Admax FCI Safford U.S.