Estimating the Prevalence of Entrapment in Post-9/11 Terrorism Cases, 105 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amicus Brief for Aref and Hossain

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK YASSIN AREF, Petitioner, Case No. 1:04-CR-402 (TJM) V. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. MOHAMMED MOSHARREF HOSSAIN, Petitioner, Case No. 1:04-CR-402 (TJM) V. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. Proposed AMICUS BRIEF Project SALAM, the Muslim Solidarity Committee And the Masjid As Salaam ________________________________________________________________________ On October 10, 2006, Yassin Muhidden Aref (hereinafter “Aref”), and Mohammed Mosharref Hossain (hereinafter “Hossain”) were convicted of terrorism-related charges in connection with an FBI sting involving the sale of a fake missile for a fictitious terrorist attack, and for money laundering. Aref was also convicted of one count of lying to the FBI. On March 8, 2007 the two defendants were sentenced to 15 years incarceration each. Their appeals to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and to the U.S. Supreme Court were denied, and they have exhausted their appellate remedies. Aref and Hossain have petitioned this court pursuant to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Section 2255 for, among other issues, the appointment of an independent prosecutor to review their cases to determine if the government and the courts provided them with necessary exculpatory information, a fair trial and justice. They seek relief similar to what was granted in People v. Theodore Stevens (a Stevens review), or what the Inspector General of the Department of Justice recommended in his June 10, 2009 Report to correct the failure of the Justice Department to identify and provide exculpatory information in terrorism cases – an independent review. Amici, Muslim Solidarity Committee (hereinafter “MSC”), Project SALAM (hereinafter “SALAM”), and the Masjid As-Salaam respectfully submit this Amicus brief, pursuant to Rule 29 in support of the defendants 2255 petition and to present information which may assist the court in deciding the issues raised by the defendants, especially where the defendants are unrepresented. -

Download a PDF of the Toolkit Here

This toolkit was created through a collaboration with MediaJustice's Disinfo Defense League as a resource for people and organizations engaging in work to dismantle, defund, and abolish systems of policing and carceral punishment, while also navigating trials of police officers who murder people in our communities. Trials are not tools of abolition; rather, they are a (rarely) enforced consequence within the current system under the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) for people who murder while working as police officers. Police are rarely charged when they commit these murders and even less so when the victim is Black. We at MPD150 are committed to the deconstruction of the PIC in its entirety and until this is accomplished, we also honor the need for people who are employed as police officers to be held to the same laws they weaponize against our communities. We began working on this project in March of 2021 as our city was bracing for the trial of Derek Chauvin, the white police officer who murdered George Floyd, a Black man, along with officers J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane while Tou Thao stood guard on May 25th, 2020. During the uprising that followed, Chauvin was charged with, and on April 20th, 2021 ultimately found guilty of, second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter. Municipalities will often use increased police presence in an attempt to assert control and further criminalize Black and brown bodies leading up to trials of police officers, and that is exactly what we experienced in Minneapolis. During the early days of the Chauvin trial, Daunte Wright, a 20-year-old Black man was murdered by Kim Potter, a white Brooklyn Center police officer, during a traffic stop on April 11th, 2021. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

Entrapment, Shocked Consciences, and the Staged Arrest Bennett L

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1982 Entrapment, Shocked Consciences, and the Staged Arrest Bennett L. Gershman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gershman, Bennett L., "Entrapment, Shocked Consciences, and the Staged Arrest" (1982). Minnesota Law Review. 890. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/890 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Entrapment, Shocked Consciences, and the Staged Arrest Bennett L. Gershman* I. INTRODUCTION On November 1, 1973, in the Criminal Court of the City of New York, Kings County, Stephen Vitale was arraigned on a charge of armed robbery. According to the complaining wit- ness, Morton Hirsch, Vitale placed a pistol against Hirsch's head, threatened him, and robbed him of over $8,000. The sup- porting affidavit of Police Officer Brian Cosgrove stated that as Vitale was fleeing from the robbery scene, Cosgove arrested him and seized a pistol from him.' On the surface, this proceeding appeared no different from thousands of similar proceedings taking place daily in criminal courts throughout the country. In fact, Vitale, Hirsch, and Cos- grove were undercover agents; New York's Special Anti-Cor- ruption Prosecutor had authorized their activities 2 as part of a program to detect corruption in the criminal justice system. 3 False court documents, false statements made to judges, and * Associate Professor of Law, Pace University School of Law. -

The War on Terror As a Self-Inflicted Disaster Ian S

*ğĕĖġĖğĕĖğĥ 3065*/( 10-*$:3&1035 Our Own Strength Against Us The War on Terror as a Self-Inflicted Disaster Ian S. Lustick* April 2008 &YFDVUJWF4VNNBSZ The War on Terror is much more than a colos- serious terrorist threat cannot even be a topic of sal waste. It is the most potent threat Americans public discussion. Politicians, the news media, face to their liberties and security. With one rival government agencies, defense contractors, spectacular blow al-Qaeda managed to exploit lobbyists of all kinds, universities, and the enter- the fantasies of a “New American Century” ca- tainment industry battle ferociously to increase bal inside the Bush administration and sucker revenues and pump up reputations by posing as the American people and its leaders into a re- more committed to winning the War on Terror sponse that serves its interests. The overstated, than their competitors. Frustrated by their in- but publicly honored, “War on Terror” and the ability to find any evidence of serious terrorist catastrophic invasion of Iraq associated with it activities in the U.S., law enforcement and re- rescued the jihadi movement from oblivion by lated agencies escalate techniques of pre-emp- convincing most of the Muslim world that ji- tive prosecution and entrapment to justify their hadi propaganda about the “infidel Christians enormous budgets. and Jews” was actually correct. Terror is a problem, but the War on Terror, At home, Americans have been so bam- because it turns U.S. power against America, is boozled by the hysterical imagery of the War on a catastrophe. Terror that the absence of evidence of a truly *Ian S. -

Framing 'Jihadjane'

What’s Love Got To Do With It? Framing ‘JihadJane’ in the US Press Maura Conway Dublin City University, Ireland Lisa McInerney University of Limerick, Ireland Abstract The purpose of this article is to compare and contrast the US press coverage accorded to female terrorist plotter, Colleen LaRose, with that of two male terrorist plotters in order to test whether assertions in the academic literature regarding media treatment of women terrorists stand up to empirical scrutiny. The authors employed TextSTAT software to generate frequency counts of all words contained in 150 newspaper reports on their three subjects and then slotted relevant terms into categories fitting the commonest female terrorist frames, as identified by Nacos’s article in Studies in Conflict and Terrorism (2005). The authors’ findings confirm that women involved in terrorism receive significantly more press coverage and are framed vastly differently in the US press than their male counterparts. Keywords: female, framing, gender, jihadi, Colleen LaRose, newspapers, press, terrorism, women __________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction This article analyses US press reports on a woman and two men arrested in the US in 2009 and 2010 for their parts in three separate jihadi terrorist plots. The female plotter is widely known as ‘JihadJane’, which was an online pseudonym for Colleen LaRose, an American woman charged with four terrorism-related offences and taken into custody by US law enforcement at Philadelphia International Airport on her return from Europe in October 2009 (Shiffman, 2011).[1] LaRose is accused of using the internet to recruit individuals for the purpose of engaging in violent jihad, to include the murder of Swedish cartoonist Lars Vilks. -

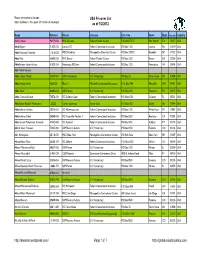

USA Prisoner List As of 1/2/2012 Page

Please remember to include USA Prisoner List return address in the upper left corner of envelope as of 1/2/2012 Name Number Prison Line one Line Two Town State Postcode Country Aafia Siddiqui 90279-054 FMC Carswell Federal Medical Center P.O. Box 27137 Fort Worth TX 76127 USA Abad Elfgeeh 31523-053 Loretto FCI Federal Correction Institution PO Box 1000 Loretto PA 15940 USA Abdel Hameed Shehadeh 11815-022 MDC Brooklyn Metropolitan Detention Center PO Box 329002 Brooklyn NY 11232 USA Abdel Nur 64655-053 FMC Butner Federal Medical Center PO Box 1600 Butner NC 27509 USA Abdelhaleem Hasan Ashqar 41500-054 Petersburg FCI Low Federal Correction Institution PO Box 1000 Petersburg VA 23804 USA Abdi Mahdi Hussein Abdul Hakim Murad 37437-054 USP Terre Haute U.S. Penitentiary PO Box 33 Terre Haute IN 47808 USA Abdul Hamin Awkal A267328 Man CI Mansfield Correctional Institution P. O. Box 788 Mansfield OH 44901 USA Abdul Kadir 64656-053 USP Canaan U.S. Penitentiary P.O. Box 300 Waymart PA 18472 USA Abdul Tawala Alishtari 70276-054 FCI Coleman Low Federal Correctional Institution P.O. Box 1031 Coleman FL 33521 USA Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad 150550 Varner Supermax Varner Unit P.O. Box 400 Grady AR 71644 USA Abdulrahman Farhane 58376-054 FCI Allenwood Low Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 1000 White Deer PA 17887 USA Abdulrahman Odeh 26548-050 FCI Victorville Medium II Federal Correctional Institution PO Box 5300 Adelanto CA 92301 USA Abdurahman Muhammad Alamoudi 47042-083 FCI Ashland Federal Correction Institution PO Box 6001 Ashland KY 41105 USA Adham Amin Hassoun 72433-004 USP Florence Admax U.S. -

Boston University Law Review

Boston University Law Review VOLUME XXI APRIL, 1941 NUMBER 2 STATE INDEMNITY FOR ERRORS OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE EDWIN BORCIIARD*BORCHARD* All too frequently the public is shocked by the news that Federal or State authorities have convicted and imprisoned a person subse-subse quently proved to have been innocent of any crime. These acciacci- dents in the administration of the criminal law happen either through an unfortunate concurrence of circumstances or perjured testimony or are the result of mistaken identity, the conviction having been obob- tained by zealous prosecuting attorneys on circumstantial evidence. In an earnest effort to compensate in some measure the victims of these miscarriages of justice, Congress in May 1938 enacted a law "to grant relief to persons erroneously convicted in courts of the United States." Under this law, any person who can prove that he was wrongwrong- fully convicted and sentenced for a crime against the United States may bring suit in the Court of Claims against the Federal Government for damages of not more than $5,000. The Federal act of May 24, 1938, limits the right of recovery to innocent persons who have been both convicted and served all or a part of their sentence. The innocence must be proved either by appeal or new trial or rehearing in which innocence is established, or by a pardon on the ground of innocence. ItIt must also appear that the en~oneouslyerroneously convicted person either committed none of the acts with which he was charged or that those acts constituted no crime against the United States or against any State or Territory. -

Learning About Learning from Error James M

Ideas in POLICE American FOUNDATION Number 14 Policing May 2012 Learning About Learning From Error James M. Doyle here has been a lot of tragedies, can be replaced by justice practitioners may be ready learning from error going a new period dedicated to the to give it a try. There are strong T on in American criminal sustained, routine practice of arguments that the policing justice since the publication in learning from error? Criminal community can and should 1996 of the U.S. Department of Justice’s compilation of the first twenty-eight wrongful Ideas in American Policing presents commentary and insight from leading crimi- nologists on issues of interest to scholars, practitioners, and policy makers. The convictions exposed by DNA. papers published in this series are from the Police Foundation lecture series of the Does it indicate that criminal same name. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not justice practitioners can adopt necessarily represent the official position of the Police Foundation. The full series is available online at http://www.policefoundation.org/docs/library.html. some version of the quality © 2012 Police Foundation. All rights reserved. reform initiatives that have reshaped other high-risk fields James M. Doyle, a Boston attorney, is currently a Visiting Fellow such as aviation and medicine? at the National Institute of Justice, where he is examining the Can the criminal justice system utility of the organizational-accident model for understanding and embrace “a theory of work, avoiding system-level errors in criminal justice. He has written which conceptualize[s] the extensively on the issue of eyewitness identification testimony continual improvement of in criminal cases, including a fourth edition of his treatise for quality as intrinsic to the work lawyers, Eyewitness Testimony: Civil and Criminal, and the itself” (Kenney 2008, 30)? historical narrative, True Witness: Cops, Courts, Science, and the Is it possible that the current Battle Against Misidentification. -

The Twitter Rhetoric of Racialized Police Brutality

Denison University Denison Digital Commons Denison Student Scholarship 2020 Limited calls for justice: The Twitter rhetoric of racialized police brutality Nina Cosdon Denison University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/studentscholarship Recommended Citation Cosdon, Nina, "Limited calls for justice: The Twitter rhetoric of racialized police brutality" (2020). Denison Student Scholarship. 33. https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/studentscholarship/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Denison Digital Commons. Limited calls for justice: The Twitter rhetoric of racialized police brutality Nina Raphaella Cosdon Project Advisor: Dr. Omedi Ochieng Department of Communication Denison University Summer Scholars Project 2020 Cosdon 2 Abstract This research sought to understand how Americans respond to racialized police violence by examining discourse conducted in the social medium, Twitter. To that end, it does a close reading of Twitter discourse to excavate the social ideologies that structure how racialized violence is conceptualized. It aimed to illuminate the possibilities and limits of Twitter as both a forum for public discourse and a technological medium of communication. After weeks of analyzing the rhetoric of Twitter users speaking against police brutality, the findings suggest that the vast majority are calling for conservative, status quo-enforcing reforms to the corrupt policing they claim to oppose. Additionally, this research concludes that Twitter, though an effective space for spreading awareness and garnering support for activist causes, is limited in its ability to enact social change. Cosdon 3 We are in the midst of a civil rights movement. -

Witness to Abuse Human Rights Abuses Under the Material Witness Law Since September 11

Human Rights Watch June 2005 Vol. 17, No. 2 (G) Witness to Abuse Human Rights Abuses under the Material Witness Law since September 11 Summary......................................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations......................................................................................................................... 7 To the Justice Department ...................................................................................................... 7 To Congress............................................................................................................................... 8 To the Judiciary......................................................................................................................... 9 I. The Material Witness Law: Overview and Pre-September 11 Use.................................. 10 Overview of the Material Witness Law ............................................................................... 12 Arrest of Material Witnesses before September 11 ........................................................... 14 II. Post-September 11 Material Witness Detention Policy................................................... 15 III. Misuse of the Material Witness Law to Hold Suspects as Witnesses........................... 17 Suspects Held as Witnesses................................................................................................... 20 Prolonged Incarceration and Undue Delays in Presenting Witnesses -

Facebook As a Reflection of Race- and Gender-Based Narratives Following the Death of George Floyd

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Exceptional Injustice: Facebook as a Reflection of Race- and Gender-Based Narratives Following the Death of George Floyd Patricia J Dixon and Lauren Dundes * Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, 2 College Hill, Westminster, MD 21157, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 November 2020; Accepted: 8 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Following the death of George Floyd, Facebook posts about the Black Lives Matter movement (BLM) surged, creating the opportunity to examine reactions by race and sex. This study employed a two-part mixed methods approach beginning with an analysis of posts from a single college student’s Facebook newsfeed over a 12-week period, commencing on the date of George Floyd’s death (25 May 2020). A triangulation protocol enhanced exploratory observational–archival Facebook posts with qualitative data from 24 Black and White college students queried about their views of BLM and policing. The Facebook data revealed that White males, who were the least active in posting about BLM, were most likely to criticize BLM protests. They also believed incidents of police brutality were exceptions that tainted an otherwise commendable profession. In contrast, Black individuals commonly saw the case of George Floyd as consistent with a longstanding pattern of injustice that takes an emotional toll, and as an egregious exemplification of racism that calls for indictment of the status quo. The exploratory data in this article also illustrate how even for a cause célèbre, attention on Facebook ebbs over time. This phenomenon obscures the urgency of effecting change, especially for persons whose understanding of racism is influenced by its coverage on social media.