Philips Park House, Prestwich Greater Manchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 OLD LAUND BOOTH See FENCE OLDHAM, St James (Prestwich

OO OLD LAUND BOOTH see FENCE OLDHAM, St James (Prestwich); Diocese of Manchester For original registers enquire at Manchester Central Library Local Studies Unit. See introduction for contact details. C 1830-1848 M 1830-1837 B 1830-1848 Copy BT Microfilm DRM 2/242a-247 C 1830-1837 M 1836-1837 B 1830-1837 Copy reg/BT Printed LPRS 165 D 1830-1919 MI Microfiche Searchroom OLDHAM, St Mary (Prestwich); Diocese of Manchester For original registers enquire at Manchester Central Library Local Studies Unit. See introduction for contact details. C 1604-1641, 1665-1844 M 1604-1641, 1665-1790 B 1604-1641, 1665-1844 Copy BT Microfilm DRM 2/234-246 C 1558-1661 M 1598-1661 B 1558-1661 Copy reg Printed Searchroom C 1558-1682 M 1558-1682 B 1558-1682 Copy reg Printed LPRS 157 B 1558-1932 Copy reg CD Searchroom M 1598-1812 Index Microfiche Boyd M 1813-1830 Index Microfiche Searchroom M 1831-1837 Index Microfiche Searchroom D to 1935 MI Transcript DRM 5/8 MI Microfilm MF 1/296-298 (Owen MSS) OLDHAM, St Peter (Prestwich); Diocese of Manchester For original registers enquire at Manchester Central Library Local Studies Unit. See introduction for contact details. C 1768-1846, 1865-1880 B 1768-1846 Copy BT Microfilm DRM 2/236a-249 For references in bold e.g.PR 3054 please consult catalogues for individual register details and the full reference. For records in the Searchroom held on microfiche, microfilm or in printed or LPRS format, please help yourself or consult a member of the Searchroom Team. -

The Hibbert Trust: a History

T HIBBERT TRUST A HISTORY THE HIBBERT TRUST A HISTORY Alan R Ruston FOREWORD The Book of the Hibbert Trust published in 1933 provided the only printed record of the work of the Hibbert Trust. It contains basic documents but is incomplete as a history. The Trustees welcomed the agreement of Alan Ruston to produce a more complete and updated account of the work of the Trust since its foundation giving him a free hand as to the form it would take. This book provides a stimulating account of many unfamiliar ,. t3;t;+;~~~~U episodes in Unitarian history including the controversial back- www.unitarian.org.uWdocs ground to the setting up and early operation of the Trust. It is interesting to note that some of the issues involved are reflected in current controversies within the Unitarian movement. Further, Mr Ruston having analysed the successes and failures of the Trustees' endeavours has provided valuable points as to future developments. The Trustees warmly appreciate the thoroughness with which he has pursued his researches in writing this book. Stanley J. Kennett Chairman ' Copyright 0A. R. Ruston ISBN 0 9507535 1 3 4' , - * . - -. d > Published 1984 by The Hibbert Trust 14 Gordon Square, London WClH OAG Printed in Great Britain by Bookmag, Henderson Road, Inverness CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................... Author's Preface .......................................................... Abbreviations used in the text ........................................ Robert Hibbert and his Trust .................................. -

Parkside Hotel for Sale Long Leasehold 281 Bury Old Road, Prestwich, Lancashire, M25 1JA Licenced Premises Guide Price £275,000 Plus VAT Sole Selling Agents

LICENSED | LEISURE | COMMERCIAL Parkside Hotel For Sale Long Leasehold 281 Bury Old Road, Prestwich, Lancashire, M25 1JA Licenced Premises Guide Price £275,000 plus VAT Sole Selling Agents • Prominent two storey public house fronting the popular Heaton Park • Conveniently located near the junction of the M60, M62 and M66 motorways • Private function room located at first floor level • Spacious three-bedroom private owners accommodation • Exciting opportunity to build upon the existing wet and dry sales 0113 8800 850 Second Floor, 17/19 Market Place, Wetherby, Leeds, LS22 6LQ [email protected] www.jamesabaker.co.uk Parkside Hotel For Sale Long Leasehold Licenced Premises 281 Bury Old Road, Prestwich, Lancashire, M25 Guide Price £275,000 plus VAT 1JA Sole Selling Agents Location Prestwich is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, Greater Manchester with a population of circa 31,700, conveniently located near the junction of the M60, M62 and M66 motorways. It is situated 3 miles north of Manchester city centre, 3 miles north of Salford and 4 miles south of Bury. The property fronts the popular Heaton Park, and is surrounded by a number of commercial and licensed occupiers and private residential dwellings. Accommodation The Parkside Hotel is a two storey semi-detached, brick and stone built property with part painted facade and single storey addition to the side, which sits beneath a number of pitched tile roofs. The exterior of the property appears to be in reasonable condition, however the internal would benefit from some minor cosmetic updating. Furnished in a traditional style throughout, the internal trading area comprises an open plan bar/lounge positioned around a central servery, which is arranged for informal drinking and dining, capable of accommodating up to circa 70 covers. -

Your Local Award-Winning Estate Agent

Issue 20 - December 2015 PRESTWICH WHITEFIELD www.pwlocalmag.com (See Page 9) Delivered FREE to over 23,000 homes in Prestwich & Whitefield each and every month CHRISTMAS AVAILABLE THROUGHOUT DECEMBER LUNCH 12PM-5:30PM - 2 COURSE MEAL £11.95 PER HEAD EVENING 5:30PM-10:30PM - 2 COURSE MEAL 20% Discount on £14.95 PER HEAD take-out ** CHRISTMAS DAY ** 2 COURSE MEAL £24.95 PER HEAD ** NEW YEARS EVE ** 2 COURSE MEAL £29.95 PER HEAD FOR MENUS FOR THE ABOVE PLEASE RING OR VISIT WEBSITE Open 7 Days Noon-11pm | www.istanbulgrills.co.uk t: 0161 798 8897 458 Bury New Rd, Prestwich. M25 1AX Since opening our big yellow door over a year ago, we’ve got the North Manchester property market wrapped up and to say thank you we have the perfect Christmas present for you! 50% DISCOUNT FOR HOMEOWNERS ON SALES AND LETTINGS FEES to anyone who calls about their property in DECEMBER AND JANUARY And we’ve also launched a new no-frills ONLINE SERVICE, where we can market your home for a fixed priced, perfect for the budget conscious, just ask one of our agents for more details. Remember, if you’re looking to sell your home, just after Christmas is the best time to do it. Get in touch now and we can get your property ready for the post festive, house-hunting bonanza. There’s massive demand for good homes in North Manchester, so if you’re looking to sell or rent, or if a new home is on your Christmas list, don’t wait. -

The Stables. ( the Old Co-Op Yard)

AVAILABLE TO LET The Stables. ( The old Co-op Yard) Warwick Street, Prestwich, Manchester, UK, Greater Manchester M25 3HB MUST BE VIEWED CONTEMPORARY OFFICE SPACE IN THE HEART OF PRESTWICH. ALL INCLUSIVE RENT. The Stables. ( The old Co-op Yard) MUST BE VIEWED Rent £550.00 pcm CONTEMPORARY OFFICE S/C Details Rents are inclusive of SPACE IN THE HEART OF service charge. PRESTWICH. ALL INCLUSIVE Rates detail Rents are inclusive of RENT. business rates.You can get small business rate The Stables, based in the Old Court Yard is a small relief if: your property’s commercial development, part of the award winning rateable value is less Bank House Studios complex. than £15,000 your business only uses one We only have one office space available!! So viewing property. Contact your is essential. local council to apply for Situated on the second floor, this 379 sq ft office small business rate relief. You will not pay consists of a open plan office space, ideal for 3-4 business rates on a workstations. Storage room, WC, sink unit and velux property with a rateable windows. value of £12,000 or less. Would suit a variety of business. Rents are inclusive of utilities (based on average Building type Office usage), business rates and service charge. Flexible lease terms may be available, subject to Planning class B1 negotiation. Available from 01/01/2020 Situated in Prestwich village and within a short walk of Prestwich Metrolink station. Size 379 Sq ft Approximately 1/2 miles of J17 of the M60 and approximately 4.8 miles from Manchester city centre. -

Your Information Request and What Happens Next

Your information request and what happens next Request Once your request is received into Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust it is redirected to the relevant Information Request Team for processing. Upon receipt of your two forms of Identification (ID) the Trust has one calendar month to provide your information. Collecting your information Once all the relevant ID has been received the Information Request Team will collate all your information, including any old paper records ready for clinical authorisation. Clinical Authorisation The Consultant who saw you last is responsible for reviewing your information. They are the most qualified person with the most up to date knowledge of your mental state and should only request redaction (removal) of information if it would result in serious harm to yourself at the time of the request. Redaction Under the Data Protection legislation, you are only entitled to your own personal data and not information relating to a third party. If your records include information that relate to a third party, we will redact the information from your record unless we have received consent from the third party to disclose the information to you. How will I know if information has been redacted from my record? Any information redacted from your notes will be identified by blocking out the relevant information as shown in the example below. This sentence has not been This sentence has been redacted redacted This sentence is to show an This sentence is to show an example of what your records example of what your records may look like if redaction has may look like if redaction has been applied. -

Fountain & Smith

COMPLETE Fountain & Smith Families Genealogy FOUNTAIN “Basket and Skip Makers” “A Link to Yorkshire” And Allied Family of SMITH Copyright © 2004, Mosaic Research and Project Management COMPLETE Fountain & Smith Families Genealogy Dedicated To Norman Spencer, Archivist at St. Marys and St. Peters Churches, Oldham Lancashire His dedication to the research of the Fountain family was phenomenal. He’s the one who put together many of the pieces from the census data and the church archives to let us know about the Fountain, Cartwright and Oldfield Families. In Memorial Margaret Joyce Fountain Acey 1937-1990 Though she died before ever passing her legacies onto her grandchildren, Some of her legacy lives on through these memories of her as a child and young woman as provided By her Mother, Elsie Taylor Fountain Paine in 1991. She was born at Beech Mount Maternity Home in Harpurhey. She was above average intelligence, bus sadly she wasn’t too fond of studying. She first went to New Moston Primary School; then for two years, with her friend Sylvia, to a Private School. After that she went back to New Moston School to prepare for taking a scholarship exam. She won a scholarship to Chadderton Grammar School which she attended for about two years. We then bought a hardware store outside of Oldham at a place called Grotton, too far for her to travel to Chadderton, so we transferred her to Hulme Grammar School, Oldham, the best school in the area. Sometime during her schooling she was sent to music lessons with a very good teacher and she was so clever that she turned out to be the star pupil at all the concerts the teacher put on and was given the most difficult pieces to perform. -

New Logistics / Manufacturing / Design & Build

of Greater Manchester... Greater of 14 13 A587 A59 12 A583 M55 32 A671 HEART the at Right 3 1 4 11 M6 A59 M65 10 A6 9 A583 A666 8 Blackpool 31 7 A584 Preston 6 Blackburn A646 30 5 A53 A59 29 A646 29 4 A56 Halifax 1 3 A582 28 M65 A644 8 19 A62 7(M) Huddersfield A666 1 A58 M6 M66 M62 Rochdale A629 D 21 M62 R Horwich Bury A58 E L 27 2 A Heywood 20 D H Bolton 3 C Rochdale A627(M) 6 A58 19 O Ormskirk R Radclie 5 N L M61 Whitefield Middleton O Oldham N L I 3 4 19 3 D 4 L 6 5 26 3 17 6 H 20 L A LN Y A 16 O E 1 21 L M Walkden 15 H N M58 22 R 1 U A Royal R 14 Wardley B 6 Oldham D 2 Hospital 25 A627 7 7 6195 M6 A580 B North Manchester OLD M RD 12 H A 24 Golf Club A 1 3 A6010 23 A628 Mills Hill 6 6 7 A580 11 1 M57 23 G MI 4 10 RIM Middleton DD S LET 24 3 H ON Oldham Knowsley 4 A RD M62 6 W 62 Manchester 6 LN Y A 22 A M67 A Wallasey 11 F 102 OX A W A5058 D L Chadderton 15 E N D 9 NT N 0 5 O 2 4 5 A 6 A56 J20 M62 / J21 M60 8 A 6 B 7 4 B 2 O 1 3 6 2 21 3 2 1 Source: Google Maps 6 LOCATION DRIVE TIMES 18 RA553 M60 3 9 B Birkenhead Warrington Chadderton, Oldham, Greater Manchester B 9 R Liverpool 3 A5300 A557 4 O A • Strategically located within 1.5 miles of Destination Miles Time 3 5 20 A 1 6 A562 Hackley D 19 2 both Junction 20 of the M62 motorway20 7 8 6 G 6 J21 M607 1 4 mins A6 B M53 A56 Golf Club APrestatyn A41 andSpek Junctione 21 of the M60 motorway.9 VICT T ORI E 4 Llandudno A A A5137 Manchester V 10 J20 M62 Airport 4 6 mins Rhyl E E 2 Bromborough • Liverpool Five miles northA533 of Manchester City Centre. -

Manchester 1874-1876 New Church ACCRINGTON St

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason ACCRINGTON School Chapel ACCRINGTON, St. James Lancashire Manchester 1874-1876 New Church ACCRINGTON St. Mary Magdalene ACCRINGTON, St. James Lancashire Manchester 1897-1904 New Church ACCRINGTON St. Paul, Barnfield ACCRINGTON, Christ Church Lancashire Manchester 1911-1913 New Church ACCRINGTON St. Peter ACCRINGTON, St. James Lancashire Manchester 1885-1889 New Church ALTHAM St. James ALTHAM Lancashire Manchester 1858-1859 Enlargement ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE Christ Church ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE, Christ Church Lancashire Manchester 1858-1860 Repairs ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE St. Peter ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE, St. Peter Lancashire Manchester 1934-1935 Repairs AUDENSHAW St. Hilda AUDENSHAW, St. Hilda Lancashire Manchester 1936-1938 New Church BACUP St. John the Evangelist BACUP, St. John the Evangelist Lancashire Manchester 1854-1874 Rebuild BACUP St. John the Evangelist BACUP, St. John the Evangelist Lancashire Manchester 1878-1884 Rebuild BAMBER BRIDGE St. Saviour BAMBER BRIDGE Lancashire Manchester 1869-1870 Enlargement BARROW-IN-FURNESS Mission Church WHALLEY, St. Mary Lancashire Manchester 1891 New Church BELFIELD St. Anne MILNROW, St. James Lancashire Manchester 1911-1913 New Church BENCHILL St. Luke the Physician BENCHILL Lancashire Manchester 1937-1939 New Church BIRCH St. Mary BIRCH Lancashire Manchester 1951-1952 Repairs BIRTLE CUM BAMFORD St. Michael, Bamford BIRTLE CUM BAMFORD, St. Michael, Bamford Lancashire Manchester 1883-1885 New Church BLACKBURN Mission Church BLACKBURN, All Saints Lancashire Manchester 1881 New Church BLACKBURN School Chapel BLACKBURN, St. Paul Lancashire Manchester 1876 Other BLACKBURN St. Bartholomew, Ewood LIVESEY, St. Andrew Lancashire Manchester 1908-1911 New Church BLACKBURN St. James BLACKBURN, St. John the Evangelist Lancashire Manchester 1872-1874 New Church BLACKBURN St. -

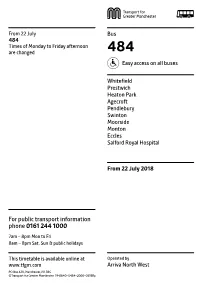

484 Times of Monday to Friday Afternoon Are Changed 484 Easy Access on All Buses

From 22 July Bus 484 Times of Monday to Friday afternoon are changed 484 Easy access on all buses Whitefield Prestwich Heaton Park Agecroft Pendlebury Swinton Moorside Monton Eccles Salford Royal Hospital From 22 July 2018 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Arriva North West PO Box 429, Manchester, M1 3BG ©Transport for Greater Manchester 19-0640–G484–2000–0519Rp Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Arriva North West large print, Braille or recorded information 73 Ormskirk Road, Aintree phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Liverpool, L9 5AE Telephone 0344 800 4411 Easy access on buses Journeys run with low floor buses have no Travelshops steps at the entrance, making getting on Eccles Church Street and off easier. Where shown, low floor Mon to Fri 7.30am to 4pm buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Saturday 8am to 11.45am and 12.30pm to space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the 3.30pm bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Sunday* Closed easy access services where these services are *Including public holidays scheduled to run. Using this timetable Timetables show the direction of travel, bus numbers and the days of the week. Main stops on the route are listed on the left. Where no time is shown against a particular stop, the bus does not stop there on that journey. -

Unitarian Members of Parliament in the Nineteenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository Unitarian Members of Parliament in the Nineteenth Century A Catalogue D. W. Bebbington Professor of History, University of Stirling The catalogue that follows contains biographical data on the Unitarians who sat in the House of Commons during the nineteenth century. The main list, which includes ninety-seven MPs, is the body of evidence on which the paper on „Unitarian Members of Parliament in the Nineteenth Century‟ is based. The paper discusses the difficulty of identifying who should be treated as a Unitarian, the criterion chosen being that the individual appears to have been a practising adherent of the denomination at the time of his service in parliament. A supplementary list of supposed Unitarian MPs, which follows the main list, includes those who have sometimes been identified as Unitarians but who by this criterion were not and some who may have been affiliated to the denomination but who were probably not. The borderline is less sharp than might be wished, and, when further research has been done, a few in each list may need to be transferred to the other. Each entry contains information in roughly the same order. After the name appear the dates of birth and death and the period as an MP. Then a paragraph contains general biographical details drawn from the sources indicated at the end of the entry. A further paragraph discusses religious affiliation and activities. Unattributed quotations with dates are from Dod’s Parliamentary Companion, as presented in Who’s Who of British Members of Parliament. -

FOR SALE 2 Acres Manchester City Centre Development Opportunity North View, Dantzic Street, Manchester M4 4JE

CIS Piccadilly Gardens Arndale Tower Corn Trinity Shopping Exchange Way Northern Centre Quarter Manchester Victoria Arena Cooperative Station & Building Metrolink Ancoats Angel Meadow Green Quarter Proposed Development River Irk 2 ACRES SITE Dantzic Street FOR SALE 2 Acres Manchester City Centre Development Opportunity North View, Dantzic Street, Manchester M4 4JE Consent For 415 Apartments Together With Commercial And Amenity Space Plus 153 Car Parking Spaces The Opportunity Description • An exciting development • Highly desirable location on the opportunity in the heart of the outskirts of the popular Northern TheNew site Cross is roughly redevelopment square and area Quarter and Ancoats extendsof Manchester to approximately City Centre 0.8Ha • The site has the benefit of being •(2 Planning acres). application submitted sold with vacant possession and Planningfor 14 apartments consent has comprising been granted in shell condition for10no. a single two-bedroom apartment andbuilding • Fantastic residential location arranged4no. one-bedroom around a central apartments communal with regards to amenity, courtyard and which varies from transport and leisure offering 5 to 24 storeys in height. The consent provides for 130 one bed apartments, 262 two bed, two bath apartments and 23 three bed, three bath apartments. In addition there is consent for 268m2 of commercial space, car parking and public space including a resident’s gym. Measured on an NIA basis the floor 1 Proposed Site 7 Arndale 11 Beetham area of the residential element 2 Ancoats Shopping Tower extends to 27,643m2 (297,549ft2). 1 3 Co-operative Centre 12 Three Towers The overall GIA is 41,511m2 Building 8 CIS Tower (Sisters) (446,824ft2).