N Uganda 06 2007 Rev3.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resettlement Action Plan RCC Reinforced Cement Concrete RMNP Rwenzori Mount National Park Iii

RESETTLEMENT AND COMPENSATION ACTION PLAN FOR THE PROPOSED SINDILA MINI HYDROPOWER PROJECT IN SINDILA SUB-COUNTY, BUNDIBUGYO DISTRICT, UGANDA. Prepared for: Butama Hydro-Electricity Company Limited Plot 41, Nakasero Road P. O. Box 9566 Kampala, Uganda Prepared by: Following a Gap Analysis against IFC Performance Standards, identified gaps plugged in and RAP Updated by: Atacama Consulting Plot 23 Gloucester Avenue, Kyambogo P.O. Box 12130 Kampala, Uganda SEPTEMBER 2014 CERTIFICATION We, the undersigned, certify that we have participated in the preparation (Butama Hydro- Electricity Company) and update (Atacama Consulting) of the Resettlement and Compensation Action Plan (RAP) for the proposed Sindila Mini Hydropower Project, to be located on River Sindila in Sindila Sub-County, Bundibugyo District, Uganda. Updating of the RAP as undertaken by Atacama Consulting was focused on addressing the gaps identified following a gap analysis, bench-marking the RAP against the requirements of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards (PS). The integrity of the original RAP as prepared by Butama Hydro-Electricity Company Limited remains the same. We hereby certify that the particulars provided when addressing the identified gaps as included in this updated RAP are correct and true to the best of our knowledge. Name Key role Signature RAP Preparation by: Mr. LPD Dayananda Team Leader/Sociologist Mr. Joseph Ovon Land Surveyor Mr. Alex Katikiro (BSc) Surveyor/Land Valuer Specialist Mr. Sangeetha Environmental Officer Mr. Krishantha Project Manager RAP Update (this document) by: (Atacama Consulting) Team Leader Mr. Edgar Mugisha Miss Juliana Keirungi Report Review and Quality Control Dr. Dauda Waiswa Batega RAP Specialist/Sociologist Mr. -

Ministry of Health

UGANDA PROTECTORATE Annual Report of the MINISTRY OF HEALTH For the Year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 Published by Command of His Excellency the Governor CONTENTS Page I. ... ... General ... Review ... 1 Staff ... ... ... ... ... 3 ... ... Visitors ... ... ... 4 ... ... Finance ... ... ... 4 II. Vital ... ... Statistics ... ... 5 III. Public Health— A. General ... ... ... ... 7 B. Food and nutrition ... ... ... 7 C. Communicable diseases ... ... ... 8 (1) Arthropod-borne diseases ... ... 8 (2) Helminthic diseases ... ... ... 10 (3) Direct infections ... ... ... 11 D. Health education ... ... ... 16 E. ... Maternal and child welfare ... 17 F. School hygiene ... ... ... ... 18 G. Environmental hygiene ... ... ... 18 H. Health and welfare of employed persons ... 21 I. International and port hygiene ... ... 21 J. Health of prisoners ... ... ... 22 K. African local governments and municipalities 23 L. Relations with the Buganda Government ... 23 M. Statutory boards and committees ... ... 23 N. Registration of professional persons ... 24 IV. Curative Services— A. Hospitals ... ... ... ... 24 B. Rural medical and health services ... ... 31 C. Ambulances and transport ... ... 33 á UGANDA PROTECTORATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Annual Report For the year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 I.—GENERAL REVIEW The last report for the Ministry of Health was for an 18-month period. This report, for the first time, coincides with the Government financial year. 2. From the financial point of view the year has again been one of considerable difficulty since, as a result of the Economy Commission Report, it was necessary to restrict the money available for recurrent expenditure to the same level as the previous year. Although an additional sum was available to cover normal increases in salaries, the general effect was that many economies had to in all be made grades of staff; some important vacancies could not be filled, and expansion was out of the question. -

Assessment of the Capacity of Ugandan Health Facilities, Personnel, and Resources to Prevent and Control Noncommunicable Diseases

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Public Health Theses School of Public Health January 2014 Assessment Of The aC pacity Of Ugandan Health Facilities, Personnel, And Resources To Prevent And Control Noncommunicable Diseases Hilary Eileen Rogers Yale University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl Recommended Citation Rogers, Hilary Eileen, "Assessment Of The aC pacity Of Ugandan Health Facilities, Personnel, And Resources To Prevent And Control Noncommunicable Diseases" (2014). Public Health Theses. 1246. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl/1246 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Health at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Health Theses by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSESSMENT OF THE CAPACITY OF UGANDAN HEALTH FACILITIES, PERSONNEL, AND RESOURCES TO PREVENT AND CONTROL NONCOMMUNICABLE DISEASES By Hilary Rogers A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Yale School of Public Health in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Public Health in the Department of Chronic Disease Epidemiology New Haven, Connecticut April 2014 Readers: Dr. Adrienne Ettinger, Yale School of Public Health Dr. Jeremy Schwartz, Yale School of Medicine ABSTRACT Due to the rapid rise of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), the Uganda Ministry of Health (MoH) has prioritized NCD prevention, early diagnosis, and management. In partnership with the World Diabetic Foundation, MoH has embarked on a countrywide program to build capacity of the health facilities to address NCDs. -

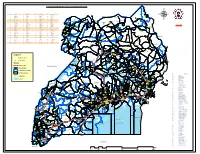

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Conflict's Children: the Human Cost of Small Arms in Kitgum and Kotido, Uganda a Case Study

Conflict’s Children: the human cost of small arms in Kitgum and Kotido, Uganda A case study January 2001 Conflict’s Children: the human cost of small arms in Kitgum and Kotido, Uganda Table of Contents Maps of Uganda and of administrative boundaries of Kitgum and Kotido Districts Methodology, constraints, and a note about the researchers 1/ Executive Summary 2/ Proliferation of small arms in Kitgum and Kotido Districts Background General situation Types and sources of small arms 3/ Impact on general population Displacements Deaths/injuries Abductions and returnees Other violations of human rights 4/ Impact on vulnerable groups Children Women and men Young people and elderly people 5/ Impact on the social sector Education Health 6/ Other impacts Food supplies The balance of power 7/ Conclusion Appendix 1 Selected information on Kotido and Kitgum Districts Appendix 2 Selected socio-economic indicators for Kotido and Kitgum Districts Appendix 3 Selected testimonies on violations of human rights by LRA, Boo-Kec, UPDF, and cattle rustlers Appendix 4 Questionnaire on the impact of small arms on the population in Kitgum and Kotido Districts, January 2001 Appendix 5 List of the interviewees from Kitgim and Kotido Cover photograph: Geoff Sayer/Oxfam 1 Conflict’s Children: the human cost of small arms in Kitgum and Kotido, Uganda Abbreviations AAA Agro-action Allemande (Welthungershilfe) AFDL Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo ALTI Aide aux Lépreux et Tuberculeux de l’Ituri APC Armée du Peuple Congolaise CAC Communauté -

Conflict in Uganda Dominic Rohner, Mathias Thoenig & Fabrizio

Seeds of distrust: conflict in Uganda Dominic Rohner, Mathias Thoenig & Fabrizio Zilibotti Journal of Economic Growth ISSN 1381-4338 Volume 18 Number 3 J Econ Growth (2013) 18:217-252 DOI 10.1007/s10887-013-9093-1 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media New York. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy J Econ Growth (2013) 18:217–252 DOI 10.1007/s10887-013-9093-1 Seeds of distrust: conflict in Uganda Dominic Rohner · Mathias Thoenig · Fabrizio Zilibotti Published online: 6 August 2013 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 Abstract We study the effect of civil conflict on social capital, focusing on Uganda’s experi- ence during the last decade. Using individual and county-level data, we document large causal effects on trust and ethnic identity of an exogenous outburst of ethnic conflicts in 2002–2005. We exploit two waves of survey data from Afrobarometer (Round 4 Afrobarometer Survey in Uganda, 2000, 2008), including information on socioeconomic characteristics at the individ- ual level, and geo-referenced measures of fighting events from ACLED. -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 Background Decentralisation reforms are currently ongoing in the majority of developing countries. The nature of decentralisation reforms vary greatly - ranging from mundane technical adjustments of the public administration largely in the form of deconcentration to radical redistribution of political power between central governments and relatively autonomous Local Governments (LGs). Decentralisation reforms hold many promises - including local level democratisation and possibly improved service delivery for the poor. However, effective implementation often lacks behind rhetoric and the effective delivery of promises also depends on a range of preconditions and the country specific context for reforms. In several countries it can be observed that decentralisation reforms are pursued in an uneven manner - some elements of the Government may wish to undertake substantial reforms - other elements will intentionally or unintentionally counter such reforms. Several different forms of decentralisation - foremost elements of devolution, deconcentration and delegation may be undertaken in either a mutually supporting or contradictory manner. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) recognises that its development assistance at the local level generally and specifically within key sectors that have been decentralised will benefit from a better understanding of the nature of decentralisation in the countries where it works. The present study on local level service delivery, decentralisation and governance in East Africa is undertaken with this in mind. The study is primarily undertaken with a broad analytical objective in mind and is not specifically undertaken as part of a programme formulation although future JICA interventions in East Africa are intended to be informed by the study. 1-2 Objective of the Study The specific objectives of the study are: 1. -

UG-08 24 A3 Fistula Supported Preventive Facilities by Partners

UGANDA FISTULA TREATMENT SERVICES AND SURGEONS (November 2010) 30°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 34°0'0"E Gulu Gulu Regional Referral Hospital Agago The Republic of Uganda Surgeon Repair Skill Status Kalongo General Hospital Soroti Ministry of Health Dr. Engenye Charles Simple Active Surgeon Repair Skill Status Dr. Vincentina Achora Not Active Soroti Regional Referral Hospital St. Mary's Hospital Lacor Surgeon Repair Skill Status 4°0'0"N Dr. Odong E. Ayella Complex Active Dr. Kirya Fred Complex Active 4°0'0"N Dr. Buga Paul Intermediate Active Dr. Bayo Pontious Simple Active SUDAN Moyo Kaabong Yumbe Lamwo Koboko Kaabong Hospital qÆ DEM. REP qÆ Kitgum Adjumani Hospital qÆ Kitgum Hospital OF CONGO Maracha Adjumani Hoima Hoima Regional Referral Hospital Kalongo Hospital Amuru Kotido Surgeon Repair Skill Status qÆ Arua Hospital C! Dr. Kasujja Masitula Simple Active Arua Pader Agago Gulu C! qÆ Gulu Hospital Kibaale Lacor Hospital Abim Kagadi General Hospital Moroto Surgeon Repair Skill Status Dr. Steven B. Mayanja Simple Active qÆ Zombo Nwoya qÆ Nebbi Otuke Moroto Hospital Nebbi Hospital Napak Kabarole Oyam Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital Kole Lira Surgeon Repair Skill Status qÆ Alebtong Dr. Abirileku Lawrence Simple Active Lira Hospital Limited Amuria Dr. Charles Kimera Training Inactive Kiryandongo 2°0'0"N 2°0'0"N Virika General Hospital Bullisa Amudat HospitalqÆ Apac Dokolo Katakwi Dr. Priscilla Busingye Simple Inactive Nakapiripirit Amudat Kasese Kaberamaido Soroti Kagando General Hospital Masindi qÆ Soroti Hospital Surgeon Repair Skill Status Amolatar Dr. Frank Asiimwe Complex Visiting qÆ Kumi Hospital Dr. Asa Ahimbisibwe Intermediate Visiting Serere Ngora Kumi Bulambuli Kween Dr. -

Understanding Deployment Policies and Systems for Staffing Rural Areas in Northern Uganda During and After the Conflict: Synthesis Report

Understanding deployment policies and systems for staffing rural areas in Northern Uganda during and after the conflict: synthesis report Richard Mangwi Ayiasi, Elizeus Rutebemberwa, Tim Martineau ReBUILD Draft Working Paper No. 26 December 2016 This is a draft Working Paper, which is subject to future revision. Please address comments to Dr Richard Mangwi ([email protected]) or Tim Martineau ([email protected]) UNDERSTANDING DEPLOYMENT POLICIES AND SYSTEMS FOR STAFFING RURAL AREAS Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place, Liverpool, L3 5QA, UK www.rebuildconsortium.com Email: [email protected] The ReBUILD Research Programme Consortium is an international research partnership funded by the UK Department for International Development. ReBUILD is working for improved access to effective health care for the poor and for reduced health costs burdens in post-conflict and post-crisis countries. We are doing this through the production of high quality, policy-relevant research evidence on health systems financing and human resources for health, and working to promote use of this evidence in policy and practice. ReBUILD is implemented by a partnership of research organisations from the UK, Cambodia, Uganda, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe. Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK Institute for Global Health & Development, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, UK Cambodia Development Resource Institute, Cambodia College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, Sierra Leone Makerere University School of Public -

Vote: 551 Sembabule District Structure of Workplan

Local Government Workplan Vote: 551 Sembabule District Structure of Workplan Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 D: Details of Annual Workplan Activities and Expenditures for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Workplan Vote: 551 Sembabule District Foreword Sembabule became a District in 1997. It has two counties – Lwemiyaga with ntuusi and Lwemiyaga Sub Counties and Mawogala with Mateete Town council, Sembabule Town council and Mateete, Lwebitakuli, Mijwala and Lugusulu sub counties hence eight lower local governments. In line with the Local Government Act 1997 CAP 243, which mandates the District with the authority to plan for the Local Governments, this Budget for the Financial Year 2014-2015 has been made comprising of; The Forward, Executive Summary, and a) Revenue Peformance and Pans, b) Summary of Departmental Performance and Plans by Work plan and c) Approved Annual Work plan Outputs for 2014-2015 which have been linked to the Medium Expenditure Plan and the District Development Plan 1011-2015. and this time the District staff list. We hope this will enable elimination of ghost workers and salary payments by 28th of every month. In line with the above, the Budget is the guide for giving an insight to the district available resources and a guide to attach them to priority areas that serve the needs of the people of Sembabule District in order to improve on their standard of living with more focus to the poor, women, youth, the elderly and people with disabilities (PWDs) although not neglecting the middle income and other socioeconomic denominations by providing improver Primary health care services, Pre Primary, Primary, secondary and tertiary Education, increasing agriculture productivity by giving farm inputs and advisory services and provision of infrastructure mainly in roads and water sectors among others . -

Patients with Nodding Syndrome in Uganda Improve with Symptomatic Treatment: a Cross-Sectional Study

Open Access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006476 on 14 November 2014. Downloaded from Patients with nodding syndrome in Uganda improve with symptomatic treatment: a cross-sectional study Richard Idro,1,2 Hanifa Namusoke,1 Catherine Abbo,3,4 Byamah B Mutamba,3,5 Angelina Kakooza-Mwesige,1,6 Robert O Opoka,1 Abdu K Musubire,7 Amos D Mwaka,7 Bernard T Opar8 To cite: Idro R, Namusoke H, ABSTRACT et al Strengths and limitations of this study Abbo C, . Patients with Objectives: Nodding syndrome (NS) is a poorly nodding syndrome in Uganda understood neurological disorder affecting thousands ▪ improve with symptomatic This is the largest cohort of patients with of children in Africa. In March 2012, we introduced a treatment: a cross-sectional nodding syndrome ever reported on to date. The study. BMJ Open 2014;4: treatment intervention that aimed to provide report examines preintervention clinical and e006476. doi:10.1136/ symptomatic relief. This intervention included sodium functional features before a well-designed treat- bmjopen-2014-006476 valproate for seizures, management of behaviour and ment intervention was implemented and how emotional difficulties, nutritional therapy and physical these improved over the course of the ensuing rehabilitation. We assessed the clinical and functional ▸ Prepublication history for year. The improvements in patients with nodding this paper is available online. outcomes of this intervention after 12 months of syndrome were also compared with those of a To view these files please implementation. similar cohort with other epilepsies. visit the journal online Design: This was a cross-sectional study of a cohort ▪ However, we did not conduct a prospective (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ of patients with NS receiving the specified intervention. -

Ogwal Kasimiro Et Al.Pdf

Third RUFORUM Biennial Meeting 24 - 28 September 2012, Entebbe, Uganda Research Application Summary Dissemination of agricultural technologies: A new approach for Uganda Ogwal Kasimiro, Okello, J., Wakulira, M., Kiyini, R., Mwebaze, M. & Yiga, D. National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) Secretariat, P.O. Box 25235, Kampala, Uganda Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Uganda with an estimated current population of 34 million has had many approaches to agricultural extension service delivery but has not realised its potential level of production and productivity in agriculture. One key gap in agricultural transformation has been the weak linkage between farmers, extension workers and research for effective technology transfer. The Government of Uganda in the National Development plan 2011/2015 identified this gap and a five year project, the Agricultural Technology and Agri-business Advisory Services (ATAAS) was formulated. The ATAAS project with five (5) components is being implemented by the National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) and National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) which are agencies of the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF). Within the first year of implementation of ATAAS, stakeholders priorities were generated, a number of adaptive research trials set in response to stakeholders needs, multiplication of planting materials undertaken and appropriate Multi-stakeholders Innovations Platforms (MSIPs) established. With support from all stakeholders and effective monitoring and evaluation conducted, ATAAS is expected to transform the agricultural sector of Uganda. However, there is need to have stronger farmer, extension and research linkages for effective technology dissemination. Responsive adaptive research trials should be established with farmers actively participating and extension workers fully guided for better results.