4.2 Betri Reykjavík

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

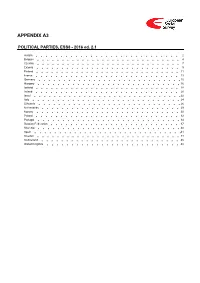

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Countries

POWER, COMMUNICATION, AND POLITICS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES POWER, COMMUNICATION, POWER, COMMUNICATION, AND POLITICS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES The Nordic countries are stable democracies with solid infrastructures for political dia- logue and negotiations. However, both the “Nordic model” and Nordic media systems are under pressure as the conditions for political communication change – not least due to weakened political parties and the widespread use of digital communication media. In this anthology, the similarities and differences in political communication across the Nordic countries are studied. Traditional corporatist mechanisms in the Nordic countries are increasingly challenged by professionals, such as lobbyists, a development that has consequences for the processes and forms of political communication. Populist polit- ical parties have increased their media presence and political influence, whereas the news media have lost readers, viewers, listeners, and advertisers. These developments influence societal power relations and restructure the ways in which political actors • Edited by: Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, & Lars Nord • Edited by: Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard communicate about political issues. This book is a key reference for all who are interested in current trends and develop- ments in the Nordic countries. The editors, Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, and Lars Nord, have published extensively on political communication, and the authors are all scholars based in the Nordic countries with specialist knowledge in their fields. Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Nordicom is a centre for Nordic media research at the University of Gothenburg, Nordicomsupported is a bycentre the Nordic for CouncilNordic of mediaMinisters. research at the University of Gothenburg, supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers. -

26 Anarchism in Iceland

Anarchism in Iceland: Is True Friendship Possible Under Capitalism Heathcote Ruthven, University of Edinburgh One month after the 2008 crash I first went to Iceland. Entertained that my pound was worth three time what it was worth the week before, I thought I would feel like a hyperinflation tourist, like Auden in Weimar Berlin, or something else equally dubious and poetic. But it was nothing like that, the gin and tonics went from £15 to £5, and my week there was one of pastries and tuna sandwiches. Five years on, after starting an Anthropology degree, I found myself wandering snowy Reykjavik on New Years Eve without a place to crash – thank you Silja and Tumi for picking me up! I interviewed a few dozen people I met in bars, and the odd journalist or politician here and there. I interviewed with little discipline or method, chatting informally and filling notepads. This paper, rushed together for Ethnographic Encounters, is firstly a call to arms; attempting to convince anthropologists that Iceland is a worthwhile topic of study, and suggest some approaches. I hope it to be an accurate portrayal of events, but is merely what I took from discussions with Icelandic friends. I must ask forgiveness for the disorganisation of this paper, it was written on my birthday in a foreign city with no library to hand and little time. If you would like more information on the sources, please email [email protected]. At the end of the 20th century, for reasons not worth going into, Iceland underwent a neoliberal revolution - extreme growth followed by extreme crashes. -

Sniðmát Meistaraverkefnis HÍ

Master‘s thesis in International Affairs Who Are the Populists in Iceland? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Icelandic Voters Jimena Klauer Morales February 2020 Who Are the Populists in Iceland? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Icelandic Voters Jimena Klauer Morales Final thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a MA degree in International Affairs Instructor(s): Gunnar Helgi Kristinsson Faculty of Political Science School of Social Sciences, University of Iceland February 2020 Who Are the Populists in Iceland? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Icelandic Voters This final thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of a MA degree in International Affairs. The thesis may not be copied in any form without the author’s permission. © Jimena Klauer Morales, 2020 ID number (110588-5189). Reykjavik, Iceland, 2020 Abstract Populism has become a buzz word, as everyone, from politicians to the media, throw the term around without much regard to what it truly means. The great majority of the research on populism has been focused on radical right-wing populist movements across Europe, and less attention has been given to left or center populist movements. Additionally, most research focuses on the causes of populism, and less so on the characteristics of the individuals who display populist attitudes. For this reason, the purpose of this research is to identify the individual-level attributes and party preferences of populist supporters in Iceland. To do this, the thesis analyzes the repercussions of the 2008 economic crisis and assesses whether the political events that followed the “crash” were the catalyst for the rise of center-left populism. Through the interpretation of the post-crisis election results, the study postulates who are the individuals who are most likely to display populist attitudes. -

Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe Refers To: A

32nd SESSION CPL32(2017)06final 29 March 2017 Local democracy in Iceland Monitoring Committee Rapporteurs1: Zdenek BROZ, Czech Republic (L, ECR) Jakob WIENEN, Netherlands (L, EPP/CCE) Recommendation 402 (2017)..................................................................................................................2 Explanatory memorandum ......................................................................................................................4 Summary This report follows the second monitoring visit to Iceland since it ratified the European Charter of Local Self-Government in 1991. It shows that the country has a satisfactory level of local democracy. The report praises recent developments fostering local self-government, including the promotion of the involvement of local authorities in national decision-making and increased inter-municipal co-operation and citizen participation in local authorities. In particular, it underlines that the national and local authorities were able to deal with a major financial crisis and its economic and social consequences without undermining local self-government. Nevertheless, the rapporteurs draw the authorities’ attention to the absence of a clear division of responsibilities between central government and local authorities, the lack of direct applicability of the Charter in the domestic legal system and the fact that the capital, Reykjavik, has not been granted a special status in accordance with Recommendation 219 (2007). Lastly, local authorities still do not have adequate resources for performing all their functions. The Congress recommends that the Icelandic authorities clarify the division of responsibilities between central government and local authorities and pass legislation to give the Charter legal force in Iceland’s domestic legal system. It also urges them to provide local authorities with adequate and sufficient financial resources and grant the city of Reykjavik a special status to take account of its particular needs compared to other municipalities. -

Better Reykjavik and Open Policy Innovation

JeDEM 7(2): 137-161, 2015 ISSN 2075-9517 http://www.jedem.org Escaping the Middleman Paradox: Better Reykjavik and Open Policy Innovation Derek Lackaff School of Communications, Elon University, Elon, North Carolina 27244, [email protected] Abstract: Better Reykjavik is a unique municipal ePetition website that is developed and maintained by a grassroots nonprofit organization, has significant deliberative mechanisms, and has been normalized as an ongoing channel for citizen-government interaction across multiple elected administrations. The primary contribution of this study is an analysis of the novel “interface” that was established between the grassroots-developed technical system and the existing political and administrative institutions of policymaking. The paper begins with a brief overview of the challenges that citizens and governments face in the implementation of ePetition processes. Landemore’s (2012) “democratic reason” and Coleman’s (2008) “autonomous citizenship” constructs provide useful insights into why and how the Better Reykjavik has made a continuing impact on city governance. Next, an analysis of the socio-technical process of the initiative’s software development and political integration is presented, showing how this project moved from the fringes of the grassroots towards the center of public and governmental awareness. Finally Reykjavik’s “new normal” political culture is examined, which illustrates how a bottom-up, fast-moving technical initiative can productively support the slower-moving processes of democratic governance. Keywords: ePetitions, eDemocracy, eGovernance, crowdsourcing, cocreation, open innovation Acknowledgement: The author gratefully acknowledges the support and cooperation of Gunnar Grímsson and Róbert Bjarnason, as well as the Elon University iMedia students of “Team Iceland” who conducted several of the initial interviews. -

Better Reykjavik: Municipal Policycrafting from the Autonomous Grassroots

Better Reykjavik: Municipal Policycrafting from the Autonomous Grassroots Derek Lackaff Elon University Gunnar Grimsson Citizens Foundation Robert Bjarnason Citizens Foundation Better Reykjavik 2 Abstract Following an economic crisis which swept away much of their wealth, international regard, and trust in established political institutions, Icelanders were in a unique position to experiment with radical new approaches to governance and citizenship. One such project that has helped restructure the relationship between government and the governed is called Better Reykjavik (Betri Reykjavik). On the surface, Better Reykjavik appears to be a straightforward ePetition site, similar to those now operated by governments around the world. We suggest that Better Reykjavik is unique among similar projects for three primary reasons: first, it is developed and maintained by a grassroots nonprofit organization, and not a government, second, it has significant deliberative mechanisms, unlike many other ePetition initiatives, and third, it rapidly achieved significant buy-in from citizens, policy-makers, and public administrators and has been normalized as an ongoing channel for citizen-government interaction across multiple elected administrations. The primary contribution of the present study is an analysis of the interface between the grassroots-developed technical system and the existing political and administrative institutions of policymaking. We draw primarily upon interviews with City of Reykjavik administrators and politicians completed since 2010, but also utilize archival data including newspaper reports, committee meeting minutes, and other public information. We begin with a brief overview of eParticipation as a contextual framework for understanding the initiative, with a focus on some of the challenges governments face in their implementation processes. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Icelandic Municipalities' Handling of an Unprecedented

Strategic Public Management Journal (SPMJ), Issue No: 3, April 2016, ISSN 2149-9543, pp. 25-42 __________________________________________________________________________________ Weathering The Storm – Icelandic Municipalities’ Handling of an Unprecedented Economic Crisis Magnús Árni Skjöld MAGNÚSSON1 Abstract Within a few days in October 2008, following serious turmoil on financial markets worldwide, some 85% of the Icelandic banking sector collapsed, together with the Icelandic currency, the króna. Almost all the rest followed early in 2009. The Icelandic stock market took a nosedive. The Republic of Iceland had entered the worst economic crisis of its history. Icelandic municipalities, which had taken on an increasing burden of running the welfare state, were hard hit financially, without the ability of the state to help out. In fact, some of the post-crisis actions of the state, under IMF direction, were difficult for the municipalities. It did not make things easier that the crisis had been precluded by an unprecedented period of growth, encouraging the municipalities to borrow in international markets and invest in infrastructure that turned out to be superfluous in the post-crisis period. This paper will look at the reactions of the Icelandic municipalities to the crisis, the political implications of it, where they are now and if there are lessons that can be learned from the difficult years in the last decade. Keywords: Iceland, financial crisis, post-crisis initiative, Icelandic municipalities, reforms 1 Associate Professor, Bifröst University, Bifröst, IS-311, Borgarbyggð, Iceland, tel: +354-433-3000, fax: 433- 3001, E-mail address: [email protected] 25 Magnús Árni Skjöld MAGNÚSSON ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction Iceland was one of the early casualties of the financial crisis of 2008. -

The Panama Papers Could Bring Down Iceland's Government and Bring

The Panama Papers could bring down Iceland’s government and bring the Pirate Party to power blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/04/05/the-panama-papers-could-bring-down-icelands-government-and-bring-the-pirate-party-to-power/ 4/5/2016 The leak of several million confidential documents created by the corporate service provider Mossack Fonseca – the so called ‘Panama Papers’ – has particular implications for Iceland, with the country’s Prime Minister, Finance Minister and Minister of the Interior all linked to the affair. Benjamin Leruth writes that the government is now under severe pressure to call early elections which could well bring the Icelandic Pirate Party to power. The release of the Panama Papers will have a huge impact all around the world, but this impact is likely to be particularly profound in Iceland. According to leaked documents from Mossack Fonseca, several Icelandic politicians, former bankers and government advisors have had links to anonymous offshore companies. Three members of the Icelandic government are directly involved: the Prime Minister, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson (of the Progressive Party); Finance Minister Bjarni Benediktsson (of the Independence Party), and Minister of the Interior Ólöf Nordal (also of the Progressive Party). Even though the Prime Minister does not intend to resign, this new political scandal might trigger a new political revolution in Iceland, only eight years after the country was hit by the Great Recession. Since then, the Icelandic political landscape has changed drastically. The so-called ‘pots and pans revolution’, often considered as the most serious series of protest in the country’s history, led to the resignation of then Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, Prime Minister of Iceland. -

Populism in Iceland: Has the Progressive Party Turned Populist?

n Fræðigreinar STJÓRNMÁL & STJÓRNSÝSLA Populism in Iceland: Has the Progressive Party turned populist? Eiríkur Bergmann, Professor of Politics, Bifrost University Abstract Though nationalism has always been strong in Iceland, populist political parties did not emerge as a viable force until after the financial crisis of 2008. On wave of the crisis a completely renewed leadership took over the country’s old agrarian party, the Progressive Party (PP), which was rapidly transformed in a more populist direction. Still the PP is perhaps more firmly nationalist than populist. However, when analyzing communicational changes of the new post- crisis leadership it is unavoidable to categorize the party amongst at least the softer version of European populist parties, perhaps closest to the Norwegian Progress Party. Keywords: Populism; Progressive Party; Framsóknarflokkurinn; Iceland Introduction Right wing nationalistic populist politics have been on the rise throughout Europe, grad- ually growing in several rounds since the 1970s and heightening in wake of the financial crisis in the early new century. Though nationalism thoroughly is, and has always in modern days been, strong in Iceland, populist political parties similar to those on the European continent and throughout Scandinavia did not emerge as a viable force until at least after the financial crisis of 2008, which hit Iceland severely hard. Out of the Nordic five Iceland suffered the most profound crisis, when its entire oversized financial system came tumbling down. The currency tanked spurring rampant inflation and sud- den economic devastation (for more, see Bergmann 2014). Icelandic Review of Politics and Administration Vol 11, Issue 1 ( 33-54 ) © 2015 Contacts: Eiríkur Bergmann, [email protected] Article first published online June 23rd 2015 on http://www.irpa.is Publisher: Institute of Public Administration and Politics, Gimli, Sæmundargötu 1, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland Stjórnmál & stjórnsýsla 1. -

Iceland#.Vdw6pr8zu2s.Cleanprint

https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2015/iceland#.VdW6pR8zu2s.cleanprint Iceland freedomhouse.org A number of major political and economic developments marked the year 2014 in Iceland. Municipal elections in May heralded a change in political party leadership, with the exit of Reykjavík mayor Jón Gnarr and his Best Party, and the return of the Social Democratic Alliance (SDA) in coalition with Bright Future, the Left-Green Movement (VG), and the Pirate Party. The issue of Iceland’s relationship with the European Union (EU) was a cause of contention throughout the year, particularly after officials declined to hold a referendum about the potential withdrawal of the country’s application for EU membership. Iceland continued to contend with the consequences of its 2008 financial crash, in which a major credit crisis forced the government to nationalize three large banks. Iceland’s special prosecutor for economic crimes, Ólafur Hauksson, continued to pursue several financial fraud investigations in 2014 into major banks and individuals suspected of criminal acts related to the crash. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: Political Rights: 39 / 40 (−1) [Key] A. Electoral Process: 12 / 12 The Icelandic constitution, adopted in 1944, vests power in a president, a prime minister, the 63-seat unicameral legislature (the Althingi), and a judiciary. The Althingi, arguably the world’s oldest parliament, was established in approximately 930 AD. The largely ceremonial president is directly elected for a four-year term, and the prime minister is appointed by the president. President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson was elected to his fifth term in 2012, defeating independent journalist Thóra Arnórsdóttir.