1914 and 2014: Should We Be Worried?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trinitytrinity ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013 building legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on their enduring connection to Trinity and their investment in our future Plus: Provost Andy Orchard passes the torch s Trinity’s eco-conscience provost’smessage Trinity’s Secret Strength A farewell to a team that is PAC-ed with affection For most students, their time at Trinity simply fies by. But those Jonathan Steels, following the departure of Kelley Castle, has rede- four or fve years of living and learning and growing and gaining fned the role of Dean of Students and built both community and still linger on, long afer the place itself has been lef behind. Over consensus. Likewise, our Registrar, Nelson De Melo, had a hard act the past six years as Provost I have been privileged to meet many to follow in Bruce Bowden, but has made his indelible mark already wonderful Men and Women of College, and hear many splen- in remaking his entire ofce. did stories. I write this in the wake of Reunion, that wondrous Another of the newcomers who has recruited well and widely is weekend of memories made and recalled and rekindled, and Alana Silverman: there is renewed energy and purpose in the Ofce friendships new and old found and further fostered. In my last of Development and Alumni Afairs, to which Alana brings fresh column as Provost, it is the thought of returning to the College vision and an alternative perspective. A consequence of all this activ- that moves me most, and makes me want to look forward, as well ity across so many departments is the increased workload of Helen as back, and to celebrate those who will run the place long afer Yarish, who replaced Jill Willard, and has again through admirable this Provost has gone. -

View 2021-2022 Reading List

CALGARY ASSOCIATION OF LIFE LONG LEARNERS HOW CAN YOU THINK THAT? A POLITICAL BOOKCLUB SEPTEMBER 2021 - JUNE 2022 READING LIST ————————————————————————————————————- July - August 2021. “Summer Reads” Animal, Vegetable, Junk: A History of Food, from Sustainable to Suicidal Mark Bittman "Epic and engrossing."—The New York Times Book Review From the #1New York Times bestselling author and pioneering journalist, an expansive look at how history has been shaped by humanity’s appetite for food, farmland, and the money behind it all—and how a better future is within reach. The story of humankind is usually told as one of technological innovation and economic influence—of arrowheads and atomic bombs, settlers and stock markets. But behind it all, there is an even more fundamental driver: Food. In Animal, Vegetable, Junk, trusted food authority Mark Bittman offers a panoramic view of how the frenzy for food has driven human history to some of its most catastrophic moments, from slavery and colonialism to famine and genocide—and to our current moment, wherein Big Food exacerbates climate change, plunders our planet, and sickens its people. Even still, Bittman refuses to concede that the battle is lost, pointing to activists, workers, and governments around the world who are choosing well-being over corporate greed and gluttony, and fighting to free society from Big Food’s grip. Sweeping, impassioned, and ultimately full of hope,Animal, Vegetable, Junk reveals not only how food has shaped our past, but also how we can transform it to reclaim our future. Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World Simon Winchester “In many ways, Land combines bits and pieces of many of Winchester’s previous books into a satisfying, globe-trotting whole. -

The War That Changed Everything, by Margaret Macmillan

World War I: The War That Changed Everything By MARGARET MACMILLAN Updated June 20, 2014 10:54 p.m. ET A raiding party from the Scottish Rifles waits for the order to attack, near Arras, France, March 24, 1917. One captain said, "The waiting was always the hardest part of all." National Library of Scotland A hundred years ago next week, in the small Balkan city of Sarajevo, Serbian nationalists murdered the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary and his wife. People were shocked but not particularly worried. Sadly, there had been many political assassinations in previous years—the king of Italy, two Spanish prime ministers, the Russian czar, President William McKinley. None had led to a major crisis. Yet just as a pebble can start a landslide, this killing set off a series of events that, in five weeks, led Europe into a general war. The U.S. under President Woodrow Wilson intended to stay out of the conflict, which, in the eyes of many Americans, had nothing to do with them. But in 1917, German submarine attacks on U.S. shipping and attempts by the German government to encourage Mexico to invade the U.S. enraged public opinion, and Wilson sorrowfully asked Congress to declare war. American resources and manpower tipped the balance against the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary, and on Nov. 11, 1918, what everyone then called the Great War finally came to an end. The cold numbers capture much of the war's horror: more than 9 million men dead and twice as many again wounded—a loss of sons, husbands and fathers but also of skills and talents. -

Human Rights: History and Theory Spring 2015, Tuesday-Thursday, 2:30-3:50 P.M., KIJP 215 Dr

PJS 494, Human Rights: History and Theory Spring 2015, Tuesday-Thursday, 2:30-3:50 p.m., KIJP 215 Dr. Everard Meade, Director, Trans-Border Institute Office Hours: Tuesdays, 4-5:30 p.m., or by appointment, KIJP 126 ixty years after the passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, there’s widespread agreement over what human rights should be. And yet, what human rights are – where they come from, how best to achieve their promise, S and what they mean to people living through war, atrocity, and poverty – remains more contentious than ever. This course explores where human rights come from and what they mean by integrating them into a history of attempts to alleviate and prevent human suffering and exploitation, from the Conquest of the Americas and the origins of the Enlightenment, through the First World War and the rise of totalitarianism, a period before the widespread use of the term “human rights,” and one that encompasses the early heyday of humanitarianism. Many attempts to alleviate human suffering and exploitation do not articulate a set of rights-based claims, nor are they framed in ways that empower individual victims and survivors, or which set principled precedents to be applied in future cases. Indeed, lumping human rights together with various humanitarian interventions risks watering down the struggle for justice in the face of power at the core of human rights praxis, rendering the concept an empty signifier, a catch-all for “doing good” in the world. On the other hand, the social movements and activists who invest human rights with meaning are often ideologically eclectic, and pursue a mix of principled and strategic actions. -

Margaret Macmillan Author / Historian

Margaret MacMillan Author / Historian Margaret MacMillan is the Warden of St Antony’s College and a Professor of International History at the University of Oxford. She is the author of numerous books including PARIS 1919: Six Months that Changed the World, which won the 2003 Governor General's Award, the Samuel Johnson Prize, the PEN Hessell Tiltman Prize, the Duff Cooper Prize and was a New York Times Editors' Choice for 2002. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a Senior Fellow of Massey College, University of Toronto, Honorary Fellow of St Hilda's, University of Oxford, and sits on the Agents Caroline Dawnay Assistant Kat Aitken [email protected] 02032140931 Publications Non-Fiction Publication Details Notes HISTORY'S PEOPLE The book accompanying the 2015 Massey Lectures, HISTORY'S PEOPLE 2016 interrogates the past to ask very big questions about the role of individuals Profile and their behaviour. It really matters: the personalities of the powerful can affect-for better or worse-millions of people and the future of countries. Like all the best history, this book colours the way you see not only the past but the present. THE WAR THAT This masterful exploration of how Europe chose its path towards war will ENDED PEACE change and enrich how we see this defining moment in our history. 2013 Profile United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Publication Details Notes THE USES AND If misrepresented, the past can cause confusion, conflict and tragedy. -

South Africa Mobilises: the First Five Months of the War Dr Anne Samson

5 Scientia Militaria vol 44, no 1, 2016, pp 5-21. doi:10.5787/44-1-1159 South Africa Mobilises: The First Five Months of the War Dr Anne Samson Abstract When war broke out in August 1914, the Union of South Africa found itself unprepared for what lay ahead. When the Imperial garrison left the Union during September 1914, supplies, equipment and a working knowledge of British military procedures reduced considerably. South Africa was, in effect, left starting from scratch. Yet, within five months and despite having to quell a rebellion, the Union was able to field an expeditionary force to invade German South West Africa and within a year agree to send forces to Europe and East Africa. This article explores how the Union Defence Force came of age in 1914. Keywords: South Africa, mobilisation, rebellion, Union Defence Force, World War 1 1. Introduction In August 1914, South Africa, along with many other countries, found itself at war. It was unprepared for this eventuality – more so than most other countries. Yet, within six weeks of war being declared, the Union sent a force into neighbouring German South West Africa. This was a remarkable achievement considering the Union’s starting point, and that the government had to deal with a rebellion, which began with the invasion. The literature on South Africa’s involvement in World War 1 is increasing. Much of it focused on the war in Europe1 and, more recently, on East Africa2 with South West Africa3 starting to follow. However, the home front has been largely ignored with most literature focusing on the rebellion, which ran from September to December 1914.4 This article aims to explore South Africa’s preparedness for war and to shed some insight into the speed with and extent to which the government had to adapt in order to participate successfully in it. -

The Rhyme of History: Lessons of the Great War”

Assignment for “The Rhyme of History: Lessons of the Great War” Read the following essay, “The Rhyme of History: Lessons of the Great War,” by Margaret MacMillan. As you read, please do the following: • Make at least 3 descriptive annotations per page. o Use one color for annotations based on rhetorical strategies and how they enhance her argument o Use another color for all other annotations • Answer the following questions: o Specify what MacMillan believes is the relationship between history and human action, in at least 2-3 sentences. __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ What is MacMillan’s argument? __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ The Rhyme of History: Lessons of the Great War Margaret MacMillan Published 12/14/2013 Earlier this year I was on holiday in Corsica and happened to wander into the church of a tiny hamlet in the hills where I found a memorial to the dead from World War I. Out of a population that can have been no more than 150, eight young men, bearing among them -

THE FIRST BATTLE of the MARNE September 1914

THE FIRST BATTLE OF THE MARNE September 1914 The battle of Thillois During the night of the 11th September, the 3rd army corps from the Vth Army (General Hache) received the mission to head the following day towards la Vesle in the direction of the Saint‐Thierry Fort and Thillois. On the 12th September, the two divisions started marching. Pétain’s 6th infantry division, on the left, was on its way to Rosnay, Muizon, Châlons‐sur‐Vesle and Saint‐Thierry’s fort. General Mangin’s 5th infantry division headed towards Méry‐Prémecy, Gueux and Thillois. The 5th division marched without any trouble until the 204 hill, 2km south‐west from Gueux. Around 10 o’clock, the news broke: Gueux had just been evacuated and the road from Gueux to Thillois was cut by trenches full of enemy infantry. Two battalions from the 39th infantry regiment were sent towards Thillois and Gueux’s La Garenne. They were under the protection of two batteries based next to the 204 hill. Around noon, the enemy, who had evacuated the trenches between Gueux and Thillois without combat, was resisting in Thillois. The cavalry notified trenches on the north of Thillois, towards Champigny. Around 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the 39th infantry regiment attacked Thillois while the 74th infantry regiment attacked Gueux’s La Garenne. At 5 o’clock, the battle was frozen. The direct attack did not achieve anything. At this point, the artillery entered the battle and set aim for Thillois. The 74th Infantry Regiment, positioned on the East, and the 39th Infantry Regiment began the assault again. -

Untitled [Kevin Braam on Americans in Occupied Belgium

Edward J. Klekowski, Libby Klekowski. Americans in Occupied Belgium, 1914/1918: Accounts of the War from Journalists, Tourists, Troops and Medical staff. Jefferson: McFarland, 2014. 296 pp. $45.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-7864-7255-0. Reviewed by Kevin Braam Published on H-War (August, 2017) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air University) As the centenaries of major battles and signif‐ thors note Whitlock’s involvement or perspective icant events of the First World War occur, there is on many of the major events of WWI that are de‐ much renewed interest in scholarship of the war. scribed. One journalist who needed Whitlock’s Ed and Libby Klekowski unveil many personal ac‐ support was popular American author Richard counts of American journalists, businessmen, and Harding Davis. After remarking that the German war adventurers in Americans in Occupied Bel‐ “war machine is certainly wonderful” (p. 23) to gium, 1914-1918. Where the title of the book is behold as soldiers marched through the streets of misleading, the scholarly work conducted by the Brussels on August 20, 1914, he set out in pursuit authors vividly describes the human condition of for the front lines. He stumbled upon the advanc‐ Americans in Belgium and uncovers the horror ing German army in the city of Hal. Barely escap‐ brought against the Belgian people by the German ing death, he was ordered back to Brussels, where army. The authors captivate the reader by reveal‐ he immediately sought counsel from Brand Whit‐ ing the personal experience and individual per‐ lock. Many journalists were not as reliant on spective of the war and its effects in the context of Whitlock nor did they pursue diplomatic means major historical events or large-scale battles. -

2017 Halifax International Security Forum Plenary 1 Transcript Peace? Prosperity? Principle? Securing What Purpose?

2017 Halifax International Security Forum Plenary 1 Transcript Peace? Prosperity? Principle? Securing What Purpose? SPEAKERS: Ms. Jane Harman, Director, President and Chief Executive Officer, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Ambassador Kay Bailey Hutchison, United States Permanent Representative, United States Mission to NATO Dr. Margaret MacMillan, Professor of History, University of Toronto Dr. Constanze Stelzenmüller, Robert Bosch Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution MODERATOR: Dr. Gideon Rose, Editor, Foreign Affairs Dr. Gideon Rose: Hello everybody and welcome. My name is Gideon Rose, I'm the editor of Foreign Affairs, and we have a great panel for you today. Before we get into that, I want to make three quick points. First, as I said, I'm the editor of Foreign Affairs, and for many years, as many of you know, Foreign Affairs has been a proud media partner and sponsor of the Halifax International Security Forum. This year, I'm proud to say we are joined by a sister peer institution of foreign policy as another proud media sponsor and I'm delighted to say that because I can also delightedly say that Foreign Policy is now under the able management of somebody who's very familiar to the Halifax audience, Jonathan Tepperman, the new editor of Foreign Policy. And so we've done this as a tag team in many years past, and we're doing it again, but now we're doing it from different institutions. So welcome Foreign Policy to Halifax officially. Second, it's worth pointing out that in these times where stories of piggishness and abuse and harassment are nearly not just daily, but hourly revelations, it is nice to know that it, we can demonstrate here in Halifax that it doesn't have to be that way. -

The Uses and Abuses of History

Praise for The Uses and Abuses of History “This is an eminently sensible and humane book, lucidly and enjoyably written and argued. It is addressed to the general reader, and anyone interested in history should find it an engaging, quick read.” —The Globe and Mail “The author maintains a tone of measured, reasoned and scholarly approachability … This is history used as its own best argument.” —Toronto Star “A good quick read … a timely read.” —Guelph Mercury Praise for Margaret MacMillan “MacMillan’s approach to history is to get under the skin of figures, to see them not so much as good or evil but as all-too-human actors struggling with a task of monumental difficulty even as they represented varying and conflicting interests.” —The New York Times “MacMillan is a worldly historian with a supreme gift for seeing the big picture … and telling the best story.” —The Globe and Mail “MacMillan provides a highly readable narrative which combines detail and approachability.” —The Guardian ALSO BY MARGARET MacMILLAN Nixon in China: The Week That Changed the World Women of the Raj Canada and NATO: Uneasy Past, Uncertain Future (editor) Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World Parties Long Estranged: Canada and Australia in the Twentieth Century (editor) The Uneasy Century: International Relations 1900–1990 (editor) Canada’s House: Rideau Hall and the Invention of a Canadian Home (with Marjorie Harris and Anne L. Desjardins) Extraordinary Canadians: Stephen Leacock Based on the Joanne Goodman Lecture Series of the University of Western Ontario PENGUIN CANADA Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.) Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. -

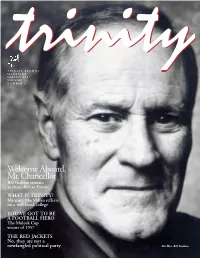

Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor

17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 1 TRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING 2007 VOLUME 44 NUMBER 2 Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor Bill Graham returns, as chancellor, to Trinity WHAT IS TRINITY? Margaret MacMillan reflects on a well-loved college YOU’VE GOT TO BE A FOOTBALL HERO The Mulock Cup victors of 1957 THE RED JACKETS No, they are not a newfangled political party The Hon. Bill Graham 17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 2 FromtheProvost The Last Word In her final column as Provost, Margaret MacMillan takes her leave with a fervent ‘Thank you, all’ hen I became Provost of this college five years not mean slavishly keeping every tradition, but picking out what was ago, I discovered all sorts of unexpected duties, important in what we inherited and discarding what was not. Estab- such as the long flower bed along Hoskin lished ways of doing things should never become a straitjacket. In W Avenue. When Bill Chisholm, then the build- my view, Trinity’s key traditions are its openness to difference, ing manager, told me on a cold January day that the Provost whether in ideas or people, its generous admiration for achievement always chose the plants, I did the only sensible thing and called in all fields, its tolerance, and its respect for the rule of law. my mother. She has looked after it ever since, with the results that I have made some changes while I have been here. Perhaps the so many of you have admired every summer. I also learned that I ones I feel proudest of are creating a single post of Dean of Students had to write this letter three times a year for the magazine.