The Rhyme of History: Lessons of the Great War”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trinitytrinity ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013 building legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on their enduring connection to Trinity and their investment in our future Plus: Provost Andy Orchard passes the torch s Trinity’s eco-conscience provost’smessage Trinity’s Secret Strength A farewell to a team that is PAC-ed with affection For most students, their time at Trinity simply fies by. But those Jonathan Steels, following the departure of Kelley Castle, has rede- four or fve years of living and learning and growing and gaining fned the role of Dean of Students and built both community and still linger on, long afer the place itself has been lef behind. Over consensus. Likewise, our Registrar, Nelson De Melo, had a hard act the past six years as Provost I have been privileged to meet many to follow in Bruce Bowden, but has made his indelible mark already wonderful Men and Women of College, and hear many splen- in remaking his entire ofce. did stories. I write this in the wake of Reunion, that wondrous Another of the newcomers who has recruited well and widely is weekend of memories made and recalled and rekindled, and Alana Silverman: there is renewed energy and purpose in the Ofce friendships new and old found and further fostered. In my last of Development and Alumni Afairs, to which Alana brings fresh column as Provost, it is the thought of returning to the College vision and an alternative perspective. A consequence of all this activ- that moves me most, and makes me want to look forward, as well ity across so many departments is the increased workload of Helen as back, and to celebrate those who will run the place long afer Yarish, who replaced Jill Willard, and has again through admirable this Provost has gone. -

View 2021-2022 Reading List

CALGARY ASSOCIATION OF LIFE LONG LEARNERS HOW CAN YOU THINK THAT? A POLITICAL BOOKCLUB SEPTEMBER 2021 - JUNE 2022 READING LIST ————————————————————————————————————- July - August 2021. “Summer Reads” Animal, Vegetable, Junk: A History of Food, from Sustainable to Suicidal Mark Bittman "Epic and engrossing."—The New York Times Book Review From the #1New York Times bestselling author and pioneering journalist, an expansive look at how history has been shaped by humanity’s appetite for food, farmland, and the money behind it all—and how a better future is within reach. The story of humankind is usually told as one of technological innovation and economic influence—of arrowheads and atomic bombs, settlers and stock markets. But behind it all, there is an even more fundamental driver: Food. In Animal, Vegetable, Junk, trusted food authority Mark Bittman offers a panoramic view of how the frenzy for food has driven human history to some of its most catastrophic moments, from slavery and colonialism to famine and genocide—and to our current moment, wherein Big Food exacerbates climate change, plunders our planet, and sickens its people. Even still, Bittman refuses to concede that the battle is lost, pointing to activists, workers, and governments around the world who are choosing well-being over corporate greed and gluttony, and fighting to free society from Big Food’s grip. Sweeping, impassioned, and ultimately full of hope,Animal, Vegetable, Junk reveals not only how food has shaped our past, but also how we can transform it to reclaim our future. Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World Simon Winchester “In many ways, Land combines bits and pieces of many of Winchester’s previous books into a satisfying, globe-trotting whole. -

The War That Changed Everything, by Margaret Macmillan

World War I: The War That Changed Everything By MARGARET MACMILLAN Updated June 20, 2014 10:54 p.m. ET A raiding party from the Scottish Rifles waits for the order to attack, near Arras, France, March 24, 1917. One captain said, "The waiting was always the hardest part of all." National Library of Scotland A hundred years ago next week, in the small Balkan city of Sarajevo, Serbian nationalists murdered the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary and his wife. People were shocked but not particularly worried. Sadly, there had been many political assassinations in previous years—the king of Italy, two Spanish prime ministers, the Russian czar, President William McKinley. None had led to a major crisis. Yet just as a pebble can start a landslide, this killing set off a series of events that, in five weeks, led Europe into a general war. The U.S. under President Woodrow Wilson intended to stay out of the conflict, which, in the eyes of many Americans, had nothing to do with them. But in 1917, German submarine attacks on U.S. shipping and attempts by the German government to encourage Mexico to invade the U.S. enraged public opinion, and Wilson sorrowfully asked Congress to declare war. American resources and manpower tipped the balance against the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary, and on Nov. 11, 1918, what everyone then called the Great War finally came to an end. The cold numbers capture much of the war's horror: more than 9 million men dead and twice as many again wounded—a loss of sons, husbands and fathers but also of skills and talents. -

Human Rights: History and Theory Spring 2015, Tuesday-Thursday, 2:30-3:50 P.M., KIJP 215 Dr

PJS 494, Human Rights: History and Theory Spring 2015, Tuesday-Thursday, 2:30-3:50 p.m., KIJP 215 Dr. Everard Meade, Director, Trans-Border Institute Office Hours: Tuesdays, 4-5:30 p.m., or by appointment, KIJP 126 ixty years after the passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, there’s widespread agreement over what human rights should be. And yet, what human rights are – where they come from, how best to achieve their promise, S and what they mean to people living through war, atrocity, and poverty – remains more contentious than ever. This course explores where human rights come from and what they mean by integrating them into a history of attempts to alleviate and prevent human suffering and exploitation, from the Conquest of the Americas and the origins of the Enlightenment, through the First World War and the rise of totalitarianism, a period before the widespread use of the term “human rights,” and one that encompasses the early heyday of humanitarianism. Many attempts to alleviate human suffering and exploitation do not articulate a set of rights-based claims, nor are they framed in ways that empower individual victims and survivors, or which set principled precedents to be applied in future cases. Indeed, lumping human rights together with various humanitarian interventions risks watering down the struggle for justice in the face of power at the core of human rights praxis, rendering the concept an empty signifier, a catch-all for “doing good” in the world. On the other hand, the social movements and activists who invest human rights with meaning are often ideologically eclectic, and pursue a mix of principled and strategic actions. -

Margaret Macmillan Author / Historian

Margaret MacMillan Author / Historian Margaret MacMillan is the Warden of St Antony’s College and a Professor of International History at the University of Oxford. She is the author of numerous books including PARIS 1919: Six Months that Changed the World, which won the 2003 Governor General's Award, the Samuel Johnson Prize, the PEN Hessell Tiltman Prize, the Duff Cooper Prize and was a New York Times Editors' Choice for 2002. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a Senior Fellow of Massey College, University of Toronto, Honorary Fellow of St Hilda's, University of Oxford, and sits on the Agents Caroline Dawnay Assistant Kat Aitken [email protected] 02032140931 Publications Non-Fiction Publication Details Notes HISTORY'S PEOPLE The book accompanying the 2015 Massey Lectures, HISTORY'S PEOPLE 2016 interrogates the past to ask very big questions about the role of individuals Profile and their behaviour. It really matters: the personalities of the powerful can affect-for better or worse-millions of people and the future of countries. Like all the best history, this book colours the way you see not only the past but the present. THE WAR THAT This masterful exploration of how Europe chose its path towards war will ENDED PEACE change and enrich how we see this defining moment in our history. 2013 Profile United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Publication Details Notes THE USES AND If misrepresented, the past can cause confusion, conflict and tragedy. -

2017 Halifax International Security Forum Plenary 1 Transcript Peace? Prosperity? Principle? Securing What Purpose?

2017 Halifax International Security Forum Plenary 1 Transcript Peace? Prosperity? Principle? Securing What Purpose? SPEAKERS: Ms. Jane Harman, Director, President and Chief Executive Officer, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Ambassador Kay Bailey Hutchison, United States Permanent Representative, United States Mission to NATO Dr. Margaret MacMillan, Professor of History, University of Toronto Dr. Constanze Stelzenmüller, Robert Bosch Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution MODERATOR: Dr. Gideon Rose, Editor, Foreign Affairs Dr. Gideon Rose: Hello everybody and welcome. My name is Gideon Rose, I'm the editor of Foreign Affairs, and we have a great panel for you today. Before we get into that, I want to make three quick points. First, as I said, I'm the editor of Foreign Affairs, and for many years, as many of you know, Foreign Affairs has been a proud media partner and sponsor of the Halifax International Security Forum. This year, I'm proud to say we are joined by a sister peer institution of foreign policy as another proud media sponsor and I'm delighted to say that because I can also delightedly say that Foreign Policy is now under the able management of somebody who's very familiar to the Halifax audience, Jonathan Tepperman, the new editor of Foreign Policy. And so we've done this as a tag team in many years past, and we're doing it again, but now we're doing it from different institutions. So welcome Foreign Policy to Halifax officially. Second, it's worth pointing out that in these times where stories of piggishness and abuse and harassment are nearly not just daily, but hourly revelations, it is nice to know that it, we can demonstrate here in Halifax that it doesn't have to be that way. -

The Uses and Abuses of History

Praise for The Uses and Abuses of History “This is an eminently sensible and humane book, lucidly and enjoyably written and argued. It is addressed to the general reader, and anyone interested in history should find it an engaging, quick read.” —The Globe and Mail “The author maintains a tone of measured, reasoned and scholarly approachability … This is history used as its own best argument.” —Toronto Star “A good quick read … a timely read.” —Guelph Mercury Praise for Margaret MacMillan “MacMillan’s approach to history is to get under the skin of figures, to see them not so much as good or evil but as all-too-human actors struggling with a task of monumental difficulty even as they represented varying and conflicting interests.” —The New York Times “MacMillan is a worldly historian with a supreme gift for seeing the big picture … and telling the best story.” —The Globe and Mail “MacMillan provides a highly readable narrative which combines detail and approachability.” —The Guardian ALSO BY MARGARET MacMILLAN Nixon in China: The Week That Changed the World Women of the Raj Canada and NATO: Uneasy Past, Uncertain Future (editor) Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World Parties Long Estranged: Canada and Australia in the Twentieth Century (editor) The Uneasy Century: International Relations 1900–1990 (editor) Canada’s House: Rideau Hall and the Invention of a Canadian Home (with Marjorie Harris and Anne L. Desjardins) Extraordinary Canadians: Stephen Leacock Based on the Joanne Goodman Lecture Series of the University of Western Ontario PENGUIN CANADA Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.) Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. -

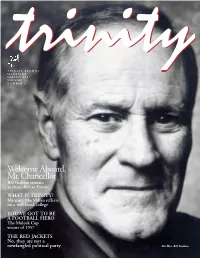

Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor

17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 1 TRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING 2007 VOLUME 44 NUMBER 2 Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor Bill Graham returns, as chancellor, to Trinity WHAT IS TRINITY? Margaret MacMillan reflects on a well-loved college YOU’VE GOT TO BE A FOOTBALL HERO The Mulock Cup victors of 1957 THE RED JACKETS No, they are not a newfangled political party The Hon. Bill Graham 17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 2 FromtheProvost The Last Word In her final column as Provost, Margaret MacMillan takes her leave with a fervent ‘Thank you, all’ hen I became Provost of this college five years not mean slavishly keeping every tradition, but picking out what was ago, I discovered all sorts of unexpected duties, important in what we inherited and discarding what was not. Estab- such as the long flower bed along Hoskin lished ways of doing things should never become a straitjacket. In W Avenue. When Bill Chisholm, then the build- my view, Trinity’s key traditions are its openness to difference, ing manager, told me on a cold January day that the Provost whether in ideas or people, its generous admiration for achievement always chose the plants, I did the only sensible thing and called in all fields, its tolerance, and its respect for the rule of law. my mother. She has looked after it ever since, with the results that I have made some changes while I have been here. Perhaps the so many of you have admired every summer. I also learned that I ones I feel proudest of are creating a single post of Dean of Students had to write this letter three times a year for the magazine. -

1 PARIS 1919 Study Guide About The

PARIS 1919 Study Guide About the Film Inspired by Margaret MacMillan’s landmark book, Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed The World, this film takes viewers inside the Paris Peace Conference offering a compelling reflection on post‐WWI history and how the decisions made during those six fateful months in 1919 continue to haunt us, for better or worse. In January 1919, Paris became the centre of the world. Armistice had been declared just a few months earlier in the most devastating war of all time. Almost ten million were dead. Two empires had collapsed. The old world order lay in tatters and a new one desperately needed to be created. Driven by unprecedented urgency, delegations from over 30 nations descended upon Paris for the most ambitious peace talks in history. The French capital became the destination of emirs and presidents, newsmen and royalty, ambitious socialites and enterprising arms dealers, each with their own agenda. At the helm of the conference were the “Big Four” of the allied victors: U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando. They endeavoured to engineer a peace treaty for all time. While the Big Four staggered under this mind‐boggling agenda, separate committees assessed war reparations and realigned national borders, forming new countries such as Iraq and Yugoslavia with little chance for reflection. Meanwhile, the streets were teeming with starving widows and war amputees – and Germany was rearming. In viewing Paris 1919 audiences will gain insight into the monumental task that lay before the Big Four and their diplomatic teams, the lasting legacies that were accomplished in the peace settlement, and the inherent weaknesses of the Paris Peace Conference. -

THE DAY THAT CHANGED the WORLD Introduction

9/11: THE DAY THAT CHANGED THE WORLD Introduction Each day the boy would look out his mountains along the Afghanistan- Focus classroom window in Brooklyn Heights Pakistan border. Five years after the with the comfort of knowing that his But some experts believe that, five attacks of Septem- father was working on the other side of years after the invasion of Afghanistan, ber 11, 2001, the world has changed the East River in the World Trade the U.S. has botched the job, leaving dramatically. This Center’s South Tower. But on this day NATO allies like Canada to do the dirty News in Review all feelings of consolation were gone. work of destroying the last vestiges of story looks at the For nine-year-old Nile Berry comfort the Taliban regime and stabilizing a significance of 9/11 was suddenly replaced by horror. As he nation that is still poverty-stricken and from its tragic beginning five looked across the river, he could see in dire need of infrastructure develop- years ago to what that both World Trade Center towers ment and financial aid. While the it might mean for were on fire. Just after 10:00 a.m., the United States continues to scale back its the world in the tower where Nile’s father worked troop commitment, many people won- 21st century. succumbed to the heat and flames that der if any nation, including Canada, has engulfed it and collapsed to the ground. the will to persevere in Afghanistan. Later that day, when David Berry failed Did you know . -

Literary Review of Canada a JOURNAL of IDEAS How Will the Next Indie Book Inspire You?

$7.95 1 2 MARLO ALEXANDRA BURKS Democracy Now KRZYSZTOF PELC Information Overload 0 2 H SHANNON HENGEN MARK LOVEWELL Atwood the Poet London, We Have a Problem C R A M Literary Review of Canada A JOURNAL OF IDEAS How will the next indie book inspire you? Expand your world. Immerse yourself. Discover new stories crafted by some of Canada’s most provocative and passionate writers. Read up. Canadian Indie Literary Publishers. AllLitUp.ca/lpg MARCH 2021 ◆ VOLUME 29 ◆ NUMBER 2 A JOURNAL OF IDEAS FIRST WORD BYGONE DAYS THIS AND THAT A Pronounced Problem The History Books Pack Together, Pack Apart Kyle Wyatt On the Cundill Prize short list Down at the dog park 3 Christopher Moore Dan Dunsky 15 FURTHERMORE 28 Robert A. Stairs, Lawrence Wardroper, At Daggers Drawn HEALTH AND WELLNESS Antanas Sileika, Joel Henderson, Margaret MacMillan soldiers on J. L. Granatstein Fragments Ian Waddell When your mother can’t 17 5 remember your name THE PUBLIC SQUARE Jigging for Answers Katherine Leyton Scratched records of 29 Slouching toward Democracy a Métis family Where have all the wise men gone? Heather Menzies LITERATURE Marlo Alexandra Burks 19 The Prophet 6 OUR NATURAL WORLD Atwood’s poetic voice Royal Descent Shannon Hengen Rideau Hall is brought down to earth Thereby Hangs a Tail 31 Mark Lovewell With the ghosts of Madagascar Alexander Sallas On the Rocks 7 Peter Unwin’s new novel 20 RULES AND REGULATIONS Larry Krotz Around the Bend 34 Wait, Wait. Don’t Tell Me The many ways rivers run through it The pros and cons of disclosure Robert Girvan Home Sweet Unhomely The latest from André Alexis Krzysztof Pelc 21 8 Spencer Morrison CLIMATE CRISIS 35 POLITICKING Whatever the Cost May Be BACKSTORY Share and Share Alike Preparing for the fight of our life How Ottawa slices the pie John Baglow Trash Talk Murray Campbell 24 Myra J. -

The Revenge of History

Bruno Tertrais The Revenge of History Vladimir Putin justifies the annexation of Crimea by its alleged role as the cradle of Russia. ISIS announces that it has erased the Sykes-Picot colonial border. Sunni Arabs see Iranian expansionism as the return of the Safavid empire. China justifies its claims in the South China Sea by “historical evidence” dating as far back as the 21st Century B.C. Throughout the world, history is making a comeback—with a vengeance. And the West is not ready. After they closed the wound open during the years 1914–1945—a true war of thirty years, three decades of self-destruction—Western countries turned their backs on major war, believing they entered an era of progress and liberty that would be freed from the barbarism of previous centuries. As a consequence, in the modern bourgeois and consumer-oriented West, the tragic nature of history risks being dangerously easy to forget, especially in “ ” Europe which would like to be post-historical, or in nstant news, crises, the United States with its relatively short history and I prevalence of lawyers in national decision-making and short election (about whom Henry Kissinger once regretted how cycles make history much they tended to be “deficient in history”).1 After a proper examination of conscience and coming to easy to overlook, if terms with their own past, liberal democracies now not forget. live in the present of instant news, current crises, and short election cycles, making history sometimes easy for decision-makers to at least overlook, if not forget. This does not mean that history is forgotten everywhere or by everyone.