4803874-4038F5-809730509322.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

Mariinsky Orchestra

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM A NOTES Friday, October 14, 2011, 8pm Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) fatalistic mockery of the enthusiasm with which Zellerbach Hall Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13, it was begun, this G minor Symphony was to “Winter Dreams” cause Tchaikovsky more emotional turmoil and physical suffering than any other piece he Composed in 1866; revised in 1874. Premiere of ever wrote. Mariinsky Orchestra complete Symphony on February 15, 1868, in On April 5, 1866, only days after he had be- Valery Gergiev, Music Director & Conductor Moscow, conducted by Nikolai Rubinstein; the sec- gun sketching the new work, Tchaikovsky dis- ond and third movements had been heard earlier. covered a harsh review in a St. Petersburg news- paper by César Cui of his graduation cantata, PROGRAM A In 1859, Anton Rubinstein established the which he had audaciously based on the same Russian Musical Society in St. Petersburg; a year Ode to Joy text by Schiller that Beethoven had later his brother Nikolai opened the Society’s set in his Ninth Symphony. “When I read this Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13, branch in Moscow, and classes were begun al- terrible judgment,” he later told his friend Alina “Winter Dreams” (1866; rev. 1874) most immediately in both cities. St. Petersburg Bryullova, “I hardly know what happened to was first to receive an imperial charter to open me.... I spent the entire day wandering aimlessly Reveries of a Winter Journey: Allegro tranquillo a conservatory and offer a formal -

The Cause of P. I. Tchaikovsky's (1840 – 1893) Death: Cholera

Esej Acta med-hist Adriat 2010;8(1);145-172 Essay UDK: 78.071.1 Čajkovski, P. I. 616-092:78.071.1 Čajkovski, P. I. THE CAUSE OF P. I. TCHAIKOVSKY’S (1840 – 1893) DEATH: CHOLERA, SUICIDE, OR BOTH? UZROK SMRTI P. I. ČAJKOVSKOG (1840.–1893.): KOLERA, SAMOUBOJSTVO ILI OBOJE? Pavle Kornhauser* SUMMARY The death of P. I. Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893) excites imagination even today. According to the »official scenario«, Tchaikovsky had suffered from abdominal colic before being infected with cholera. On 2 November 1893, he drank a glass of unboiled water. A few hours later, he had diarrhoea and started vomiting. The following day anuria occured. He lost conscious- ness and died on 6 November (or on 25 Oktober according to the Russian Julian calendar). Soon after composer's death, rumors of forced suicide began to circulate. Based on the opin- ion of the musicologist Alexandra Orlova, the main reason for the composer's tragic fate lies in his homosexual inclination. The author of this article, after examining various sources and arguments, concludes that P. I. Tchaikovsky died of cholera. Key words: History of medicine 19th century, pathografy, cause of death, musicians, P. I. Tchaikovsky, Russia. prologue In symphonic music, the composer’s premonition of death is presented in a most emotive manner in the Black Mass by W. A. Mozart and G. Verdi (which may be expected taking into account the text: Requiem aeternum dona eis …), in the introduction to R. Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde and in the last movement of G. Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. -

CHAN 10024 BOOK.Qxd 24/4/07 1:06 Pm Page 2

CHAN 10024 Front.qxd 24/4/07 1:05 pm Page 1 CHAN 10024 CHANDOS CHAN 10024 BOOK.qxd 24/4/07 1:06 pm Page 2 Anton Stepanovich Arensky (1861–1906) 1 Overture to ‘Un songe sur le Volga’, Op. 16 7:03 A Dream on the Volga Maestoso – Moderato assai – Allegro – Maestoso 2 Introduction to ‘Nal and Damayanti’, Op. 47 6:48 Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht Andante sostenuto – Allegretto – Allegro moderato – Presto – Andante sostenuto – Allegretto Suite No. 3 ‘Variations’, Op. 33 28:27 À Monsieur le Baron N. de Korff 3 Theme. Andante con moto 1:34 4 I Dialogue. Andante sostenuto 2:20 5 II Valse. Allegro 1:27 6 III Marche triomphale. Maestoso 2:18 7 IV Menuet (XVIIIème siècle) 1:22 8 V Gavotte. Allegro 4:07 9 VI Scherzo. Presto 3:54 10 VII Marche funèbre. Adagio non troppo 4:26 11 VIII Nocturne. Andantino 3:37 12 IX Polonaise. Allegro moderato 3:11 Darius Battiwalla piano Anton Stepanovich Arensky 13 Intermezzo for Orchestra, Op. 13 3:06 Dedicated to the Moscow Musical Circle in G minor • in G-Moll • en sol mineur Presto – Meno mosso – Presto – Coda. Prestissimo 3 CHAN 10024 BOOK.qxd 24/4/07 1:06 pm Page 4 Arensky: Symphony No. 2 and other works Symphony No. 2, Op. 22 21:55 Anton Arensky belongs to that unique band of 1895 to 1901 and then retired with a in A major • in A-Dur • en la majeur Russian composers (Glazunov, Lyadov, comfortable pension of six thousand roubles. 14 I Allegro giocoso 6:20 Grechaninov, Ippolitov-Ivanov and others) who Although this gave him more time to compose, 15 II Romance. -

Tchaikovsky Concerto #1

Tchaikovsky Concerto #1 Friday, March 29, 2019 at 11 am Francesco Lecce-Chong, Guest conductor Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B‐flat Major, Op. 23 Andrew von Oeyen, piano Shostakovich Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93 (select movements) Tchaikovsky concerto #1 According to Gerard The Composers McBurney in a 2006 article for The Guardian: “At the heart of both Tchaikovsky's Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich's music is (1840—1893) superlative technique and fluency, coupled with a pro- Pyotr Tchaikovsky was born on May 7, 1840 in nounced fondness for mix- Votkinsk, Russia, the second son of Ilya and Al- ing highbrow contexts, ide- exandra. Ilya was a mine inspector and this was the second marriage for as and tunes with a some- Ilya whose first wife times startlingly lowbrow Mariya had died leaving him with a young flavor (scraps of operetta, daughter, Zinaida. At pop tunes, cheap marches the time, Votkinsk Pyotr Tchaikovsky and barrel-organ noises). (about 600 miles south- east of Moscow) was This combination of high- famous for its ironworks and Ilya had considera- brow and kitsch is not ble authority as the factory manager of the Kam- theirs alone, of course. sko-Votkinsk Ironworks. Both Ilya and Alexan- dra had interests in the arts and had purchased an Many composers have orchestrion (a type of barrel organ that could The Tchaikovsky family in joined in the fun, including simulate orchestral effects) after moving to the remote Votkinsk. Tchaikovsky was particularly 1848 Mozart, Schubert and Mah- entranced by the instrument that played works of Mozart as well as the ler. -

Program Notes | All Tchaikovsky

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, January 31, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, February 1, at 2:00 Saturday, February 2, at 8:00 Kensho Watanabe Conductor Edgar Moreau Cello Tchaikovsky Capriccio italien, Op. 45 Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op. 33, for cello and orchestra Intermission Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13 (“Winter Daydreams”) I. Allegro tranquillo (Dreams of a Winter Journey) II. Adagio cantabile ma non tanto (Land of Desolation, Land of Mists) III. Scherzo: Allegro scherzando giocoso IV. Finale: Andante lugubre—Allegro moderato—Allegro maestoso—Andante lugubre—Allegro vivo This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. LiveNote® 2.0, the Orchestra’s interactive concert guide for mobile devices, will be enabled for these performances. The January 31 concert is sponsored by Jack and Ramona Vosbikian. The February 2 concert is sponsored by Ms. Elaine Woo Camarda. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 ® Getting Started with LiveNote 2.0 » Please silence your phone ringer. » Make sure you are connected to the internet via a Wi-Fi or cellular connection. » Download the Philadelphia Orchestra app from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. » Once downloaded open the Philadelphia Orchestra app. » Tap “OPEN” on the Philadelphia Orchestra concert you are attending. » Tap the “LIVE” red circle. The app will now automatically advance slides as the live concert progresses. -

Read the LIVE 2018 Disc 8 Notes

MILY BALAKIREV (1837–1910) Octet for Winds, Strings, and Piano, op. 3 (1855–1856) As a child, Mily Balakirev demonstrated promising musical Creative Capitals 2018: Liner notes, disc 8. aptitude and enjoyed the support of Aleksandr Ulïbïshev [pro- nounced Uluh- BYSHev], the most prominent musical figure The sixteenth edition of Music@Menlo LIVE visits seven of and patron in his native city of Nizhny Novgorod. Ulïbïshev, Western music’s most flourishing Creative Capitals—London, the author of books on Mozart and Beethoven, introduced the Paris, St. Petersburg, Leipzig, Berlin, Budapest, and Vienna. young Balakirev to music by those composers as well as by Cho- Each disc explores the music that has emanated from these cul- pin and Mikhail Glinka. In 1855, Balakirev traveled to St. Peters- tural epicenters, comprising an astonishingly diverse repertoire burg, where Ulïbïshev introduced him to Glinka himself. Glinka spanning some three hundred years that together largely forms became a consequential mentor to the eighteen-year-old pianist the canon of Western music. Many of history’s greatest com- and composer. That year also saw numerous important con- posers have helped to define the spirit of these flagship cities cert appearances for Balakirev. In February, he performed in St. through their music, and in this edition of recordings, Music@ Petersburg as the soloist in the first movement of a projected Menlo celebrates the many artistic triumphs that have emerged piano concerto; later that spring, also in St. Petersburg, he gave from the fertile ground of these Creative Capitals. a concert of his own solo piano and chamber compositions. -

Radio 3 Listings for 6 – 12 August 2011 Page 1

Radio 3 Listings for 6 – 12 August 2011 Page 1 of 22 SATURDAY 06 AUGUST 2011 I Crisantemi for string quartet Moyzes Quartet SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b012x18f) Jonathan Swain presents the Diamond Ensemble with Nikolaj 5:17 AM Znaider playing Mozart. Strauss, Johann Jr (1825-1899) Rosen aus dem Süden, waltz (Op.388) 1:01 AM Danish Radio Concert Orchestra, Roman Zeilinger (conductor) Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus [1756-1791] Quintet for strings (K.516) in G minor 5:27 AM Diamond Ensemble with guest Nikolaj Znaider, violin Scarlatti, Domenico [1685-1757] Sonata (Kk. 87) in B minor 1:36 AM Eduard Kunz (piano) Bartok, Bela (1881-1945) 2 Pictures for orchestra (Sz.46) (Op.10) 5:33 AM Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra in Bratislava, Bystrik Mendelssohn, Felix (1809-1847) Rezucha (conductor) Symphony for string orchestra in B minor, No.10 Risor Festival Strings 1:52 AM Prokofiev, Sergey (1891-1953) 5:43 AM Symphony No.1 in D major (Op.25), 'Classical' Wikander, David, (1884-1955) Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Michel Tabachnik (conductor) King Lily of the Valley Swedish Radio Choir, Eric Ericson (conductor) 2:07 AM Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus [1756-1791] 5:47 AM Serenade (K.361) in B flat major Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il'yich (1840-1893) Diamond Ensemble with guest Nikolaj Znaider (director) The Nutcracker: Waltz of the Flowers Slovenian Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra, Marko 3:01 AM Munih (conductor) Bizet, Georges (1838-1875) Symphony in C major 5:54 AM Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Othmar Maga (conductor) Weill, Kurt (1900-1950) Kleine Dreigroschenmusik -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 15, 2015, at 8:00 Friday, January 16, 2015, at 1:30 Saturday, January 17, 2015, at 8:00 Riccardo Muti Conductor Yefim Bronfman Piano Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major, Op. 83 Allegro non troppo Allegro appassionato Andante John Sharp, cello Allegretto grazioso YEFIM BRONFMAN INTERMISSION Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 13 (Winter Daydreams) Daydreams of a Winter Journey: Allegro tranquillo Land of Desolation, Land of Mists: Adagio cantabile ma non tanto Scherzo: Allegro scherzando giocoso Finale: Andante lugubre—Allegro maestoso These concerts are generously sponsored by the Zell Family Foundation. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major, Op. 83 Like Dürer, Goethe, and of the ideas for the piano concerto, and, at the a number of German same time, gave birth to new ones that he would composers before him, use when he returned to it. Back in Italy several Brahms found inspiration months later, Brahms was filled with feelings he in Italy. His first trip was could hardly name; he returned to Vienna noting in the spring of 1878, that it seemed “wrong” to call it home after days and, as he wrote home to of such unexpected contentment elsewhere. -

Anton Stepanovich Arensky

Mária Vojtovičová Anton Stepanovich Arensky Violin concerto in A minor, op. 54 Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Music Music Bachelor’s Thesis 16.05.2017 Abstract Mária Vojtovičová Author(s) Anton Stepanovich Arensky Title 24 pages + 1 appendix + CD: A. Arensky – Violin Concerto in A Number of Pages minor Date 23 April 2017 Degree Bachelor of Music Degree Programme Music Specialisation option Music Pedagogy Instructor(s) MuT Annu Tuovila I have chosen Anton Stepanovich Arensky and his Violin Concerto in A minor as an object of my practical and theoretical final project in Metropolia University of Applied Sciences for a very simple reason and that is, I believe he and his concert never got the attention they deserve. In the beginning of the thesis I go briefly through Arensky’s life and his entire work as there is not a lot known of him and we have very limited sources of information due to his short life and lack of interest in him. I provide a brief inside to the author’s life and work. The main part of the thesis is focused on the analysis of the concerto from the violinist’s point of view and analysis of my practicing process, suggested fingerings, bowings, and ways of interpretation. The recording of my performance of the concerto is also a part of this Bachelor’s Thesis. I believe this thesis will bring more attention to the author and this piece, as in its founda- tion it is a good repertoire choice that gives an opportunity to demonstrate the interpreter’s technical and lyrical qualities. -

Night on Bald Mountain (Original 1867 Version) (1839–1881)

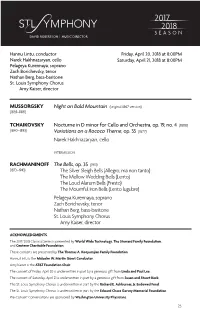

2017 2018 SEASON Hannu Lintu, conductor Friday, April 20, 2018 at 8:00PM Narek Hakhnazaryan, cello Saturday, April 21, 2018 at 8:00PM Pelageya Kurennaya, soprano Zach Borichevsky, tenor Nathan Berg, bass-baritone St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director MUSSORGSKY Night on Bald Mountain (original 1867 version) (1839–1881) TCHAIKOVSKY Nocturne in D minor for Cello and Orchestra, op. 19, no. 4 (1888) (1840–1893) Variations on a Rococo Theme, op. 33 (1877) Narek Hakhnazaryan, cello INTERMISSION RACHMANINOFF The Bells, op. 35 (1913) (1873–1943) The Silver Sleigh Bells (Allegro, ma non tanto) The Mellow Wedding Bells (Lento) The Loud Alarum Bells (Presto) The Mournful Iron Bells (Lento lugubre) Pelageya Kurennaya, soprano Zach Borichevsky, tenor Nathan Berg, bass-baritone St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The 2017/2018 Classical Series is presented by World Wide Technology, The Steward Family Foundation, and Centene Charitable Foundation. These concerts are presented by The Thomas A. Kooyumjian Family Foundation. Hannu Lintu is the Malcolm W. Martin Guest Conductor. Amy Kaiser is the AT&T Foundation Chair. The concert of Friday, April 20 is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Linda and Paul Lee. The concert of Saturday, April 21 is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Susan and Stuart Keck. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Richard E. Ashburner, Jr. Endowed Fund. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Edward Chase Garvey Memorial Foundation. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. 23 RUSSIAN ORIGINALS BY RENÉ SPENCER SALLER TIMELINKS “My music is the product of my temperament, and so it is Russian music,” Serge Rachmaninoff declared. -

Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture by Tony Hsiu Lin a Disserta

Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture By Tony Hsiu Lin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anne Nesbet, Co-Chair Professor David Frick, Co-Chair Professor Robert P. Hughes Professor James Davies Spring 2014 Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture © 2014 by Tony Hsiu Lin Abstract Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture by Tony Hsiu Lin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Anne Nesbet, Co-Chair Professor David Frick, Co-Chair Fryderyk Chopin’s fame today is too often taken for granted. Chopin lived in a time when Poland did not exist politically, and the history of his reception must take into consideration the role played by Poland’s occupying powers. Prior to 1918, and arguably thereafter as well, Poles saw Chopin as central to their “imagined community.” They endowed national meaning to Chopin and his music, but the tendency to glorify the composer was in a constant state of negotiation with the political circumstances of the time. This dissertation investigates the history of Chopin’s reception by focusing on several events that would prove essential to preserving and propagating his legacy. Chapter 1 outlines the indispensable role some Russians played in memorializing Chopin, epitomized by Milii Balakirev’s initiative to erect a monument in Chopin’s birthplace Żelazowa Wola in 1894.