A Discourse Analysis of the Representation of Islam And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download

30 June 2020 ISSN: 2560-1628 2020 No. 26 WORKING PAPER Belt and Road Initiative and Platform “17+1”: Perception and Treatment in the Media in Bosnia and Herzegovina Igor Soldo Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Wu Baiyi 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 [email protected] china-cee.eu Belt and Road Initiative and Platform “17+1”: Perception and Treatment in the Media in Bosnia and Herzegovina Igor Soldo Head of the Board of Directors, Foundation for the Promotion and Development of the Belt and Road Initiative, BiH Abstract The Belt and Road Initiative, as well as cooperation China - Central and Eastern European Countries (hereinafter: CEE) through the Platform "17+1" require the creation of a higher level of awareness of citizens about all aspects of the advantages of these foreign policy initiatives aimed at mutual benefit for both China and the participating countries. Of course, the media always play a key role in providing quality information to the general public, with the aim of better understanding all the benefits that these Chinese initiatives can bring to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Also, the media can have a great influence on decision makers by creating a positive environment and by accurate and objective information. Therefore, when it comes to media articles related to these topics, it is important to look at the situation objectively and professionally. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of the media treatment of the Belt and Road Initiative and Platform "17+1" in Bosnia and Herzegovina, quantitative measuring of the total number of media releases dealing with these topics in the media with editorial board or visible editorial policy, and their qualitative analysis, as well as the analysis of additional, special relevant articles. -

Media Intervention and Transformation of the Journalism Model in Bosnia and Herzegovina Amer Džihana*

Medij. istraž. (god. 17, br. 1-2) 2011. (97-118) IZVORNI ZNANSTVENI RAD UDK: 070(497.6) Primljeno: 23. srpnja 2011. Media Intervention and Transformation of the Journalism Model in Bosnia and Herzegovina Amer Džihana* SUMMARY Transformation of a journalistic model in Bosnia and Herzegovina is a long-term challenge both for international organizations engaged in media reform and for local media professionals who strive to establish a model according to developed democratic countries. Although enormous efforts have been made to establish a model that embraces the values of impartial, correct and fair reporting, patriotic journalism - based primarily on the principle “us against them” - remains as the norm for reporting on a great number of social events. It is believed that patri- otic journalism is the essential journalistic model when reporting about contro- versial social events where opposite perspectives of ethno-political elites occur. This claim is supported by the results of analysis of reporting about the trial of Radovan Karadžić, the former president of Republika Srpska before the Inter- national Tribunal for War Crimes. The reasons for the survival of this model are found in non-reformed political spheres that generate social divisions. Key words: media intervention, news, journalistic culture, patriotic journalism, ethnocentrism in media Introduction In spite of the comprehensive media intervention in post-war Bosnia and Herze- govina (BiH) to overcome segregation in communication among the three peoples in BiH, few believe that media represent reliable partners when mitigating the ex- * Amer Džihana, MA, Director for Research and Advocacy, Internews Network Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, BiH, PhD candidate at the Faculty of Political Sciences in Sarajevo. -

The Missing Persons Institute of Bosnia-Herzegovina

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 14 August 2009 The Problem of Ethnic Politics and Trust: The Missing Persons Institute of Bosnia-Herzegovina Kirsten Juhl Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Juhl, Kirsten (2009) "The Problem of Ethnic Politics and Trust: The Missing Persons Institute of Bosnia- Herzegovina," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 4: Iss. 2: Article 14. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol4/iss2/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Problem of Ethnic Politics and Trust: The Missing Persons Institute of Bosnia-Herzegovina Kirsten Juhl Research Fellow, University of Stavanger After the violent conflict in the 1990s, between 25,000 and 30,000 persons were missing in Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH), their fates and whereabouts unknown. Solving the missing-persons issue, and thus reducing some of the damages of the conflict, has been important in the aftermath crisis management and has been considered a prerequisite to prevent recurrences. Two of the latest developments in these efforts are the adoption of the Law on Missing Persons in October 2004 and the establishment of a state-level institution, the Missing Persons Institute (the MPI BiH) in August 2005. This article examines the missing-persons issue from a risk management and societal safety perspective aimed at creating resilient societies. -

Analysis of the Media Reporting Corruption In

ANALYSIS OF THE MEDIA REPORTING CORRUPTION IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA (15 -28. August, 2011.) Meše Selimovića 55 | Banja Luka 78000 | [email protected] | T: +387 51 221 920 | F: +387 51 221 921 | 033 222 152 | Soukbunar 42 | Sarajevo 71 000 | [email protected] | T: +387 33 200 653 | T/F: +387 33 222 152 www.prime.ba PIB: 401717540009 | JIB: 4401717540009 | JIB PJ 4401717540017 | Matični broj: 1971158 METHODOLOGICAL NOTES The basis of this analysis is the media reporting in the form of news genres or press releases whose content was dedicated to corruption in Bosnia and Herzegovina (examples of corruptive actions, research and reports on the level of corruption distribution, activities towards legal proceedings and prevention of corruption, etc.). While analyzing the media excerpts, attention was aimed toward determining the qualifications of the mentioned corruptive activities, i.e., the way they were mentioned and interpreted – who is the one that points out to the examples of corruption, who interprets them, and who is named as the perpetrator of these actions. The analysis included 135 texts and features from 9 daily newspapers (Dnevni avaz, Dnevni list, Euro Blic, Fokus, Glas Srpske, Nezavisne novine, Oslobodjenje, Press, Vecernji list), 2 weekly papers (Dani, Slobodna Bosna), 3 television stations (news programme of BHT, FTV, and RTRS, with two features from OBN and TV SA) and 7 web sites (24sata.info, bih.x.info, biznis.ba, depo.ba, dnevnik-ba, Sarajevo-x.com, zurnal.info) in the period between August 15 and 28, 2011. The excerpts were cross-referenced with each date during the analyzed period in order to estimate their frequency in newspapers, assuming that the frequency is one of the indicators of importance of the topic of corruption. -

OHR Bih Media Round-Up, 14/10/2003

OHR BiH Media Round-up, 14/10/2003 CROAT RADIO HERCEG- BH TV 1 (19,00 hrs) FED TV (19,30 hrs) RT RS (19,30) BOSNA (18,00 hrs) BiH HoR session BiH HoR session BiH Steel BL Clinical Centre Free trade with SCG Hadzipasic in Tuzla Canton BiH HoR session RS Gov on Telekom Srpske EU on ICTY Negotiations on Kosovo Short supply of passports CoM Session Negotiations on Kosovo Oslobodjenje Humanitarian worker from Sarajevo indicted for terrorism; War crimes in Mostar: Jadranko Prlic threatened with the Hague; BH Human Rights Chamber: Press release on Srebrenica on Wednesday? Dnevni Avaz Investigation into the coup d’état: Sealed envelop hides the secret; Avaz learns: Constitutional Court confirmed – Bicakcic, Covic and Garib to stay without immunity Dnevni List Terzic: Croatia requested to submit deadlines for implementation of Agreement; Proposal of law on intelligence-security service rejected Vecernji List Intelligence service needs supervision; Army left without helicopters Slobodna Features Croatia related headlines Dalmacija Glas Srpske Medicine Faculty in Banjaluka: Police on test; In Kozarac and Vlasenica: Drinks then fists Nezavisne Novine Bosko Ceko, Republika Srpska Chief Auditor: Ivanic Government was deliberately violating the laws; Representatives of the BIH House of Representatives: Public hearing of those responsible for alleged coup d’etat; The Republika Srpska Government adopted Action Plan on Telekom Srpske: Replacement of leadership was left on share-holders Blic Mladen Ivanic: When assessing the budget deficit they mixed apples -

OHR Bih Media Round-Up, 7/11/2005

OHR BiH Media Round-up, 7/11/2005 Latest radio news broadcast at 12.00 on 7 November RADIO HERCEG-BOSNA (12,00 hrs) BH Radio 1 (12,00 hrs) Incidents in France and Germany EU Foreign Ministers mtg Igman Initiative mtg started FBiH HoR on Enegropetrol FBiH HoR on Energopetrol today Violence in Paris TV news broadcast on 6 November RADIO HERCEG-BOSNA (18,00 hrs) TV PINK (18,00 hrs) BHT 1 (19,00 hrs) World news EU to discuss EC recommendations Decision on SAA negotiations Igman initiative session Igman Initiative session in Sarajevo Cavic on BiH SAA chief negotiator FBIH HoR session announcement BiH poultry industry suffers losses SCG negotiations on SAA EU Foreign Affairs Ministers meeting Feature on Banja LukaUniversity Igman initiative session commenced NTV Hayat (19,00 hrs) FTV (19,30 hrs) RTRS (19,30 hrs) Igman Initiative session in Sarajevo Igman initiative session in Sarajevo EU Foreign Affairs Ministers meeting Feature on foreign donations to BiH Marovic and Mesic visit Sarajevo Cavic on Chief SAA Negotiator World news: riots in France Brussels meeting on Const. changes Igman initiative session World Assoc. of Diaspora session Meeting on tolerance in Balkans RS POW on Ashdown Oslobodjenje Bosnians should change Dayton Agreement by their own Dnevni Avaz Croatian President Mesic: Third Entity in BiH not logical Dnevni List Vrankic denies journalists of information Vecernji List Fake invalids on Croatian budget Slobodna Dalmacija Croatia related headlines Glas Srpske Franjo was torching, Alija was encouraging Nezavisne Novine BiH should withdraw the lawsuit against SiCG Blic They are looking for a job while they are working illegally Vecernje Novosti Serbia related headlines LATEST NEWS OF TODAY EU Foreign Ministers BH Radio 1 Elvir Bucalo – EU Foreign Ministers started their meeting in to approve start of Brussels, which is expected to result with an approval of the EC’s SAA talks with BiH recommendation for opening the SAA talks with BiH. -

OHR Bih Media Round-Up, 6/10/2005

OHR BiH Media Round-up, 6/10/2005 Latest radio news broadcast at 12.00 on 6 October RADIO HERCEG-BOSNA (12,00 hrs) BH Radio 1(12,00 hrs) RTRS (12,00 hrs) HR Ashdown on RSNA’s decision Jelavic sentence RS NA regular session US welcome defence reform in BiH Prosecutors’ conference in Sa USA welcomes police ref. adoption BiH CoM in session OHR, US on police reform, SAA talks Jelavic sentenced to 10 years TV news broadcast on 5 October RADIO HERCEG-BOSNA (18,00 hrs) TV PINK (18,00 hrs) BHT 1 (19,00 hrs) BIH HoP session BIH HoP adopted Draft law on PBS RS NA discusses Cavic’s proposal HoP deputy on Croat rights Cavic’s proposal on police reform BiH HoP adopted PBS Law RS NA session RS Government on Cavic’s proposal Verdict in Mostar shells case BIH Presidency session Celebration of Dayton anniversary Kazani case trial commences NTV Hayat (19,00 hrs) FTV (19,30 hrs) RTRS (19,30 hrs) Cavic’s proposal on police reform Children/Youth centre affair Bush promises support to BIH EC on Cavic’s proposal BiH HoP adopted PBS Law RS NA adopts police reform proposal RS NA members on Cavic’s proposal FTV on new PBS Law BIH HoP session BIH HoP adopted Law on PBS BiH HoP adopted Defence law 21 arrested for organised car theft Oslobodjenje RS accepted European principles on police reform Dnevni Avaz How the quartet ‘broke’ Cavic Dnevni List Mostar mortar rounds case : 4 years in prison to Bajgoric Vecernji List House of Peoples rejected TV channel for Croats Slobodna Dalmacija Butcher from Vitez is displaced person from Zenica Nezavisne Novine RS Parliament -

Oslobodjenje Prezentacija

Oslobodjenje 1st issue (August 30, 1943) Oslobodjenje Facts ● Oslobodjenje ("liberation") was founded on August 30, 1943 in Bosnia and Herzegovina ● One of the oldest daily newspapers in South-East Europe ● Recognized by its ethnic inclusiveness and unbiased reporting during the 1992-95 war in BiH ● Global activist action in 1993, when the front cover of Oslobodjenje was printed as a supplement in newspapers all over the world ● In 2006, the company was bought by one of the leading city company Sarajevska Pivara (Sarajevo Brewery) ● Sports, cultural and specialized supplements: Sport, Biznis Plus, Auto Svijet, Kun, Antena, Pogledi, San ● In June 2016 we published the 25.000th issue of Oslobodjenje ● 2016 - Makeover and successful implementation of the StoryEditor editorial system, a Content Management System which merge database of articles, media content, page planing and ads management with Adobe applications through StoryLink client application, used by the most important media in Croatia and Slovenia War cover of Oslobodjenje Oslobodjenje Awards (selection) ● "April 6th" Award by the City of Sarajevo, 1984 (BiH)The Paper of the Year in 1989 (Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) ● The Paper of the Year Award in 1992, BBC and Granada TV (Great Britain) ● Freedom Award by Dagens nyheter-Stockholm and Politiken Copenhagen, 1993 (Denmark) ● Oscar Romero Award, The Rothko Chapel, 1993 (Houston, Texas) ● Nieman Foundation's Louis M. Lyons Award for conscience and integrity in journalism in 1993 (Harvard University - USA) ● Achievements -

Evropska Unija, Mediji I Bih / Mladen Mirosavljević. Evropska Unija U

Mladen Mirosavljević Biljana Bogdanić Izdavač Friedrich Ebert Stift ung Sarajevo Lektorka Zinaida Lakić Naslovna strana Aleksandar Aničić Priprema za štampu Friedrich Ebert Stift ung Štampa Amosgraf d.o.o Sarajevo Tiraž 300 Mladen Mirosavljević Evropska unija, mediji i BiH Biljana Bogdanić Evropska unija u štampanim medijima u BiH Sarajevo, 2010. Sadržaj Mladen Mirosavljević EVROPSKA UNIJA, MEDIJI I BiH Evropska unija, mediji i BiH ......................................................6 Medijska pismenost.....................................................................7 Štampani mediji .........................................................................10 Izvori ...........................................................................................12 Preporuka o medijskoj pismenosti .........................................12 Zabrinutost Evropskog parlamenta zbog načina izvještavanja o EU .........................................................13 EU, mediji i BiH .........................................................................14 Zaključak ....................................................................................16 Izvori ...........................................................................................19 Biljana Bogdanić EVROPSKA UNIJA U ŠTAMPANIM MEDIJIMA U BiH 1. Uvod ........................................................................................22 2. Metoda istraživanja ...............................................................23 3. Rezultati istraživanja .............................................................24 -

Bosnia-Herzegovina by Jasna Jelisic´

Bosnia-Herzegovina by Jasna Jelisic´ Capital: Sarajevo Population: 3.8 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$8,770 Source: The data above was provided by The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Electoral Process 4.25 3.75 3.50 3.25 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.25 3.25 Civil Society 4.25 4.00 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 Independent Media 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.25 4.50 4.50 4.75 Governance* 5.50 5.25 5.00 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a 4.75 4.75 4.75 5.00 5.00 5.25 5.25 Local Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.75 Judicial Framework and Independence 5.25 5.00 4.50 4.25 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.25 Corruption 5.50 5.00 4.75 4.50 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.50 4.50 4.50 Democracy Score 4.83 4.54 4.29 4.18 4.07 4.04 4.11 4.18 4.25 4.32 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Znaju O Politici?

Šta stanovnici Bosne i Hercegovine (ne) znaju o politici? Ova publikacija je nastala kao rezultat istraživačkog projekta „Koliko građani Bosne i Hercegovine znaju o politici”, koji je u potpunosti podržala Fondacija „Friedrich Ebert Stiftung”. 1 Šta stanovnici Bosne i Hercegovine (ne) znaju o politici? Izdavač Art print, Banja Luka Recenzenti prof. dr Zdravko Zlokapa prof. dr Miodrag Živanović Autori Srđan Puhalo doc. dr Berto Šalaj mr Biljana Bogdanić Lektorka Nataša Savanović Naslovna strana Srđan Puhalo Priprema za štampu Vedran Čičić Štampa Art print, Banja Luka Za izdavača i štampariju Milan Stijak Tiraž 300 primjeraka 2 Šta stanovnici Bosne i Hercegovine (ne) znaju o politici? Šta stanovnici Bosne i Hercegovine (ne) znaju o politici? Priredio: Srđan Puhalo Banja Luka 2009 3 Šta stanovnici Bosne i Hercegovine (ne) znaju o politici? 4 Šta stanovnici Bosne i Hercegovine (ne) znaju o politici? Ako ne poznajete pravila igre, niti igrače, i nije vas briga za rezultat, teško da ćete sami probati da igrate. Robert D. Patnam 5 Šta stanovnici Bosne i Hercegovine (ne) znaju o politici? 6 Šta stanovnici Bosne i Hercegovine (ne) znaju o politici? SADRŽAJ Zašto ovo istraživati? ................................................................................. 9 Dr Berto Šalaj POLITIČKO ZNANJE I DEMOKRACIJA 1. Uvod ..................................................................................................... 13 2. Suvremeno razumijevanje demokracije ............................................... 13 3. Političko znanje i demokracija ............................................................ -

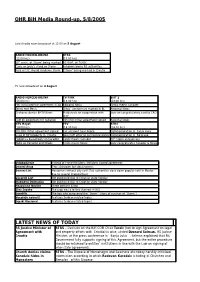

OHR Bih Media Round-Up, 5/8/2005

OHR BiH Media Round-up, 5/8/2005 Latest radio news broadcast at 12.00 on 5 August RADIO HERCEG-BOSNA RTRS (12,00 hrs) (12,00 hrs) 10th anniv. of ‘Storm’ being marked RS Govt. on Terzic Cavic on Jovic’s stand on Storm Ashdown warns RS authorities Serb ref.:IC should condemn Storm “Storm” being marked in Croatia TV news broadcast on 4 August RADIO HERCEG-BOSNA TV PINK BHT 1 (18,00 hrs) (18,00 hrs) (19,00 hrs) PMs Initialized the agreement in Zg Regional News Terzic meets Sanader Terzic met Mesic ‘Oluja’ anniversary marked in BL Regional News Grahovac denies BHTV News Matijasevic on cooperation with Jovic on congratulatory card to CRO ICTY CoM on equipment for radiation BiH-CRO initial agreement signed Regional News NTV Hayat FTV RTRS (19,00 hrs) (19,30 hrs) (19,30 hrs) BiH-CRO initial agreement signed Car accident near Zepce Commemoration in Banja Luka Issue of BiH property in Croatia New CoM affair re car licence plates Commemoration in Belgrade Podgorica based daily on Karadzic Terzic meets Sanader 10th Storm anniversary Tadic on Karadzic and Mladic Terzic meets Mesic Jovic congratulates Sanader & Mesic Oslobodjenje Instead of Prime Ministers, Ministers signed agreement Dnevni Avaz Tihic: Ashdown lost decisiveness Dnevni List Mostarians without city café (Tax authorities close down popular café in Mostar due to several irregularities) Vecernji List Not published due to Croatian state holiday Slobodna Dalmacija Not published due to Croatian state holiday Nezavisne Novine Three persons killed Glas Srpske The crop was a failure (harvest in RS) EuroBlic The boy who conquered the “Storm” (story of survivor of “Storm”) Vecernje novosti Features Serbian related topics Srpski Nacional Features Serbian related topics LATEST NEWS OF TODAY RS Justice Minister of RTRS – Decision on the BiH COM Chair Terzic (not to sign Agreement on legal Agreement with and property affairs with Croatia) is wise, stated Dzerard Selman, RS Justice Croatia Minister, at the press conference in Banja Luka .