Uromastyx Acanthinura Bell, 1825

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetic Relationships and Subgeneric Taxonomy of Toad�Headed Agamas Phrynocephalus (Reptilia, Squamata, Agamidae) As Determined by Mitochondrial DNA Sequencing E

ISSN 00124966, Doklady Biological Sciences, 2014, Vol. 455, pp. 119–124. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2014. Original Russian Text © E.N. Solovyeva, N.A. Poyarkov, E.A. Dunayev, R.A. Nazarov, V.S. Lebedev, A.A. Bannikova, 2014, published in Doklady Akademii Nauk, 2014, Vol. 455, No. 4, pp. 484–489. GENERAL BIOLOGY Phylogenetic Relationships and Subgeneric Taxonomy of ToadHeaded Agamas Phrynocephalus (Reptilia, Squamata, Agamidae) as Determined by Mitochondrial DNA Sequencing E. N. Solovyeva, N. A. Poyarkov, E. A. Dunayev, R. A. Nazarov, V. S. Lebedev, and A. A. Bannikova Presented by Academician Yu.Yu. Dgebuadze October 25, 2013 Received October 30, 2013 DOI: 10.1134/S0012496614020148 Toadheaded agamas (Phrynocephalus) is an essen Trapelus, and Stellagama) were used in molecular tial element of arid biotopes throughout the vast area genetic analysis. In total, 69 sequences from the Gen spanning the countries of Middle East and Central Bank were studied, 28 of which served as outgroups (the Asia. They constitute one of the most diverse genera of members of Agamidae, Chamaeleonidae, Iguanidae, the agama family (Agamidae), variously estimated to and Lacertidae). comprise 26 to 40 species [1]. The subgeneric Phryno The fragment sequences of the following four cephalus taxonomy is poorly studied: recent taxo mitochondrial DNA genes were used in phylogenetic nomic revision have been conducted without analysis analysis: the genes of subunit I of cytochrome c oxi of the entire genus diversity [1]; therefore, its phyloge dase (COI), of subunits II and IV of NADHdehydro netic position within Agamidae family remains genase (ND2 and ND4), and of cytochrome b (cyt b). -

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA CHORDATA 16SCCZO3 Dr. R. JENNI & Dr. R. DHANAPAL DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY M. R. GOVT. ARTS COLLEGE MANNARGUDI CONTENTS CHORDATA COURSE CODE: 16SCCZO3 Block and Unit title Block I (Primitive chordates) 1 Origin of chordates: Introduction and charterers of chordates. Classification of chordates up to order level. 2 Hemichordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Balanoglossus and its affinities. 3 Urochordata: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Herdmania and its affinities. 4 Cephalochordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Branchiostoma (Amphioxus) and its affinities. 5 Cyclostomata (Agnatha) General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Petromyzon and its affinities. Block II (Lower chordates) 6 Fishes: General characters and classification up to order level. Types of scales and fins of fishes, Scoliodon as type study, migration and parental care in fishes. 7 Amphibians: General characters and classification up to order level, Rana tigrina as type study, parental care, neoteny and paedogenesis. 8 Reptilia: General characters and classification up to order level, extinct reptiles. Uromastix as type study. Identification of poisonous and non-poisonous snakes and biting mechanism of snakes. 9 Aves: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Columba (Pigeon) and Characters of Archaeopteryx. Flight adaptations & bird migration. 10 Mammalia: General characters and classification up -

Biomechanical Assessment of Evolutionary Changes in the Lepidosaurian Skull

Biomechanical assessment of evolutionary changes in the lepidosaurian skull Mehran Moazena,1, Neil Curtisa, Paul O’Higginsb, Susan E. Evansc, and Michael J. Fagana aDepartment of Engineering, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX, United Kingdom; bThe Hull York Medical School, University of York, York YO10 5DD, United Kingdom; and cResearch Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom Edited by R. McNeill Alexander, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 24, 2009 (received for review December 23, 2008) The lepidosaurian skull has long been of interest to functional mor- a synovial joint with the pterygoid, the base resting in a pit (fossa phologists and evolutionary biologists. Patterns of bone loss and columellae) on the dorsolateral pterygoid surface. Thus, the gain, particularly in relation to bars and fenestrae, have led to a question at issue in relation to the lepidosaurian lower temporal variety of hypotheses concerning skull use and kinesis. Of these, one bar is not the functional advantage of its loss (13), but rather of of the most enduring relates to the absence of the lower temporal bar its gain in some rhynchocephalians and, very rarely, in lizards in squamates and the acquisition of streptostyly. We performed a (12, 14). This, in turn, raises questions as to the selective series of computer modeling studies on the skull of Uromastyx advantages of the different lepidosaurian skull morphologies. hardwickii, an akinetic herbivorous lizard. Multibody dynamic anal- Morphological changes in the lepidosaurian skull have been ysis (MDA) was conducted to predict the forces acting on the skull, the subject of theoretical and experimental studies (6, 8, 9, and the results were transferred to a finite element analysis (FEA) to 15–19) that aimed to understand the underlying selective crite- estimate the pattern of stress distribution. -

Stellio' in Herpetology and a Comment on the Nomenclature and Taxonomy of Agamids of the Genus Agama (Sensu Lato) (Squamata: Sauria: Agamidae)

©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at HERPETOZOA 8 (1/2): 3 - 9 Wien, 30. Juli 1995 A brief review of the origin and use of 'stellio' in herpetology and a comment on the nomenclature and taxonomy of agamids of the genus Agama (sensu lato) (Squamata: Sauria: Agamidae) Kurzübersicht über die Herkunft und Verwendung von "stellio" in der Herpetologie und Kommentar zur Nomenklatur und Taxonomie von Agamen, Gattung Agama (sensu lato) (Squamata: Sauria: Agamidae) KLAUS HENLE ABSTRACT The name 'stellio' has received a wide and variable application in herpetology. Its use antedates modern nomenclature. The name was applied mainly to various agamid and gekkonid species. In modern usage, confu- sion exists primarily with its use as a genus, i. e., Siellio. To solve this problem, STEJNEGER (1936) desig- nated Siellio saxatilis of LAURENTI, 1768 which is based on a figure in SEBA (1734) as the type species. This species is unidentifiable. In an unpublished thesis, MOODY (1980) split the genus Agama (s. 1.) into six genera. He overlooked STEJNEGER's (1936) designation and reused Stellio for the stellio-group of agamid lizards. Many authors followed MOODY (1980). Recently, some authors pointed out that Siellio is unavailable but did not fully dis- cuss the implications for agamid nomenclature. It is argued that a satisfactory nomenclature is difficult with current knowledge of agamid taxonomy. It is suggested to restrict Laudakia to L. tuberculata and to use Ploce- denna for the stellio-group (sensu stricto). KURZFASSUNG Der Name "stellio" sah eine breite und vielfältige Verwendung in der Herpetologie, die weit über die moderne Nomenklatur zurückreicht. -

Report on Species/Country Combinations Selected for Review by the Animals Committee Following Cop16 CITES Project No

AC29 Doc. 13.2 Annex 1 UNEP-WCMC technical report Report on species/country combinations selected for review by the Animals Committee following CoP16 CITES Project No. A-498 AC29 Doc. 13.2 Annex 1 Report on species/country combinations selected for review by the Animals Committee following CoP16 Prepared for CITES Secretariat Published May 2017 Citation UNEP-WCMC. 2017. Report on species/country combinations selected for review by the Animals Committee following CoP16. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge. Acknowledgements We would like to thank the many experts who provided valuable data and opinions in the compilation of this report. Copyright CITES Secretariat, 2017 The UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) is the specialist biodiversity assessment centre of UN Environment, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. The Centre has been in operation for over 30 years, combining scientific research with practical policy advice. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission, provided acknowledgement to the source is made. Reuse of any figures is subject to permission from the original rights holders. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose without permission in writing from UN Environment. Applications for permission, with a statement of purpose and extent of reproduction, should be sent to the Director, UNEP-WCMC, 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 0DL, UK. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UN Environment, contributory organisations or editors. The designations employed and the presentations of material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UN Environment or contributory organisations, editors or publishers concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries or the designation of its name, frontiers or boundaries. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Uromastyx by Catherine Love, DVM Updated 2021

Uromastyx By Catherine Love, DVM Updated 2021 Natural History Uromastyx, also known as spiny-tailed or dabb lizards, are a genus of herbivorous, diurnal lizards found in northern Africa, the Middle East, and northwest India. This genus of lizard is in the agamid family, the same family as bearded dragons and frilled lizards. There are 13 recognized uromastyx species, but not all are commonly kept in captivity in the United States. U. aegyptia (Egyptian), U. ornatus (ornate), U. geyri (saharan), U. nigriventris (Moroccan), U. dispar (Mali), and U. ocellata (ocellated) are some of the most commonly kept. Uros dig burrows or spend time in rocky crevices to protect themselves from the elements in their desert habitats. These lizards naturally inhabit rocky terrain in very arid climates and are often found basking in direct sunlight. Characteristics and Behavior Uros tend to be quite docile and tolerant of handling, with some owners even claiming their lizard seeks out interaction. These lizards don’t tend to bite, but can be skittish if time is not taken to tame them. Ornate uromastyx have been noted to be bolder, while Egyptian and Moroccan uromastyx may be more shy. As with other members of the agamid family, uromastyx do not possess tail autotomy (they can’t drop their tails). Uros are heat loving, mid-day basking lizards that thrive in arid environments. Uros have a gland near their nose that excretes salt, which may cause a white build-up near their nostrils (keepers affectionately refer to this build-up as “snalt”). They are fairly hardy and handleable lizards that make good pets for intermediate keepers. -

Gross Trade in Appendix II FAUNA (Direct Trade Only), 1999-2010 (For

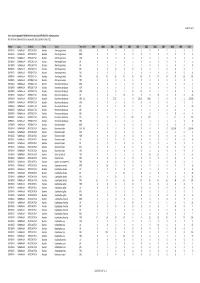

AC25 Inf. 5 (1) Gross trade in Appendix II FAUNA (direct trade only), 1999‐2010 (for selection process) N.B. Data from 2009 and 2010 are incomplete. Data extracted 1 April 2011 Phylum Class TaxOrder Family Taxon Term Unit 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Total CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia BOD 0 00001000102 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia BON 0 00080000008 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia HOR 0 00000110406 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia LIV 0 00060000006 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKI 1 11311000008 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKP 0 00000010001 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKU 2 052101000011 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia TRO 15 42 49 43 46 46 27 27 14 37 26 372 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Antilope cervicapra TRO 0 00000020002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae BOD 0 00100001002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae HOP 0 00200000002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae HOR 0 0010100120216 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae LIV 0 0 5 14 0 0 0 30 0 0 0 49 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae MEA KIL 0 5 27.22 0 0 272.16 1000 00001304.38 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae MEA 0 00000000101 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae -

Deep‐Time Convergent Evolution in Animal Communication Presented

Received: 18 November 2020 | Revised: 15 April 2021 | Accepted: 19 April 2021 DOI: 10.1111/ele.13773 LETTER Deep- time convergent evolution in animal communication presented by shared adaptations for coping with noise in lizards and other animals Terry J. Ord1 | Danielle A. Klomp1 | Thomas C. Summers1 | Arvin Diesmos2 | Norhayati Ahmad3 | Indraneil Das4 1Evolution & Ecology Research Centre Abstract and the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New Convergence in communication appears rare compared with other forms of ad- South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia aptation. This is puzzling, given communication is acutely dependent on the envi- 2Herpetology Section, Zoology Division, National Museum of the Philippines, ronment and expected to converge in form when animals communicate in similar Manila, Philippines habitats. We uncover deep- time convergence in territorial communication between 3Department of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Universiti Kebangsaan two groups of tropical lizards separated by over 140 million years of evolution: Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia the Southeast Asian Draco and Caribbean Anolis. These groups have repeatedly 4Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation, Universiti converged in multiple aspects of display along common environmental gradients. Malaysia Sarawak, Kota Samarahan, Malaysia Robot playbacks to free- ranging lizards confirmed that the most prominent con- vergence in display is adaptive, as it improves signal detection. We then provide Correspondence Terry J. Ord, Evolution & Ecology evidence from a sample of the literature to further show that convergent adap- Research Centre and the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental tation among highly divergent animal groups is almost certainly widespread in Sciences, University of New South Wales, nature. -

Uromastyx Ocellata Lichtenstein, 1823

AC22 Doc. 10.2 Annex 6e Uromastyx ocellata Lichtenstein, 1823 FAMILY: Agamidae COMMON NAMES: Eyed Dabb Lizard, Ocellated Mastigure, Ocellated Uromastyx, Eyed Spiny-tailed Lizard, Smooth-eared (English); Fouette-queue Ocellé (French); Lagarto de Cola Espinosa Ocelado (Spanish) GLOBAL CONSERVATION STATUS: Currently being assessed by IUCN Global Reptile Assessment. SIGNIFICANT TRADE REVIEW FOR: Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan Range States selected for review Range Exports* Urgent, Comments States (1994-2003) possible or least concern Djibouti 0 Least concern No trade reported Egypt 4 528 Least concern Export of species banned since 1992. No exports recorded since 1995. Eritrea 0 Least concern No trade reported Ethiopia 477 Least concern Ethiopia’s CITES Authorities confirm its presence. Trade levels low. Export quotas in place based on population surveys. Somalia 0 Least concern No trade reported Sudan 11,702 Least concern Main exporter; low levels of trade (<3000 yr-1). No systematic population monitoring in place to determine non-detriment. SUMMARY Uromastyx ocellata, commonly known in the pet trade as the Ocellated Spiny-tailed Lizard, is recorded from Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan. Ethiopia’s CITES Scientific Authority also report that the species is found in that country. It is found in wadis in rocky mountainous desert with acacia trees. U. ocellata is reportedly fairly common in some range States, although regarded as declining in some areas. If it occurs at population densities comparable to those of other Uromastyx species, its population is likely to number at minimum several hundred thousand individuals. Reported exports of U. ocellata during the period 1994-2003 were mainly from Sudan (11,702) and Egypt (4,528) with Ethiopia also exporting specimens.