Gilberto Gil's Song Lyric Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Música E Identidade De Marca: Uma Análise De Conteúdo Sobre a Atuação Da Marca Farm No Spotify

Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisuais e Publicidade Música e identidade de marca: uma análise de conteúdo sobre a atuação da marca Farm no Spotify Luana Gomes Gandra Coutinho Brasília 2019 Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisuais e Publicidade Luana Gomes Gandra Coutinho Música e identidade de marca: uma análise de conteúdo sobre a atuação da marca Farm no Spotify Projeto final em Publicidade e Propaganda apresentado à Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação em Publicidade e Propaganda. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Elton Bruno Pinheiro Brasília 2019 Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisuais e Publicidade Luana Gomes Gandra Coutinho Projeto Final aprovado em ___/___/___ para obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação Publicidade e Propaganda. BANCA EXAMINADORA ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Elton Bruno Pinheiro DAP/FAC/UnB | Orientador ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Edmundo Brandão Dantas DAP/FAC/UnB | Examinador ______________________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Suelen Brandes Marques Valente DAP/FAC/UnB | Examinadora ______________________________________________________ Prof. Me. Mauro Celso Maia FAC/UnB | Suplente Brasília 2019 Tudo o que uma marca faz pode ser entendido como um capítulo da sua história, contada com o objetivo de reforçar o seu significado e, como consequência, envolver os que se identificam com tais narrativas. (Ronaldo Fraga). Agradecimentos Aos meus pais, a minha família e amigos, pelo apoio, pelo suporte e pela companhia nessa caminhada. A Suelen, Edmundo e Mauro, por aceitarem compor a banca e participar desse projeto muito especial para mim. A Rafa e Clara por compartilharem comigo essa experiência e terem feito dela mais feliz e prazerosa. -

Minister of Counterculture

26 Guardian Weekly December 23 2005-January 5 2006 Culture Gilberto Gil is a musical legend - and now a senior Brazilian politician. He tz Minister of counterculture Gilberto Gil wears a sober suit and tie these days, and his dreadlocks are greying at the temples. But you soon remember that, as well as the serving culture minister of Brazil, you are in the presenceof one of the biggest l,atin American musicians of the 60s and 70s when you ask him about his intellectual influences and he cites Timothy l,eary. "Oh, yeah!" Gil says happily, rocking back in his chair at the Royal SocietyoftheArts in London. "Forexam- ple, all those guys at Silicon Valley - they're all coming basically from the psychedelic culture, you know? The brain-expanding processesof the crystal had a lot to do with the internet." Much as it may be currently de rigueur for journalists to ask politicians whether or not they have smoked marijuana, the question does not seem worth the effort. Gil's constant references to the hippy counterculture are not simplythe nostalgia of a 63-year-old with more than 4O albums to his name. For several years now, largely under the rest of the world's radar, the Braeilian government has been building a counterculture ofits own. The battlefield has been intellectual property - the ownership ofideas - and the revolution has touched everything, from internet file- sharing to GM crops to HIV medication. Phar- maceutical companies selling patented Aids drugs, for example, were informed that Brazil would simply ignore their claims to ownership and copy their products more cheaply if they didn't offer deep discounts. -

RETRATOS DA MÚSICA BRASILEIRA 14 Anos No Palco Do Programa Sr.Brasil Da TV Cultura FOTOGRAFIAS: PIERRE YVES REFALO TEXTOS: KATIA SANSON SUMÁRIO

RETRATOS DA MÚSICA BRASILEIRA 14 anos no palco do programa Sr.Brasil da TV Cultura FOTOGRAFIAS: PIERRE YVES REFALO TEXTOS: KATIA SANSON SUMÁRIO PREFÁCIO 5 JAMELÃO 37 NEY MATOGROSSO 63 MARQUINHO MENDONÇA 89 APRESENTAÇÃO 7 PEDRO MIRANDA 37 PAULINHO PEDRA AZUL 64 ANTONIO NÓBREGA 91 ARRIGO BARNABÉ 9 BILLY BLANCO 38 DIANA PEQUENO 64 GENÉSIO TOCANTINS 91 HAMILTON DE HOLANDA 10 LUIZ VIEIRA 39 CHAMBINHO 65 FREI CHICO 92 HERALDO DO MONTE 11 WAGNER TISO 41 LUCY ALVES 65 RUBINHO DO VALE 93 RAUL DE SOUZA 13 LÔ BORGES 41 LEILA PINHEIRO 66 CIDA MOREIRA 94 PAULO MOURA 14 FÁTIMA GUEDES 42 MARCOS SACRAMENTO 67 NANA CAYMMI 95 PAULINHO DA VIOLA 15 LULA BARBOSA 42 CLAUDETTE SOARES 68 PERY RIBEIRO 96 MARIANA BALTAR 16 LUIZ MELODIA 43 JAIR RODRIGUES 69 EMÍLIO SANTIAGO 96 DAÍRA 16 SEBASTIÃO TAPAJÓS 44 MILTON NASCIMENTO 71 DORI CAYMMI 98 CHICO CÉSAR 17 BADI ASSAD 45 CARLINHOS VERGUEIRO 72 PAULO CÉSAR PINHEIRO 98 ZÉ RENATO 18 MARCEL POWELL 46 TOQUINHO 73 HERMÍNIO B. DE CARVALHO 99 CLAUDIO NUCCI 19 YAMANDU COSTA 47 ALMIR SATER 74 ÁUREA MARTINS 99 SAULO LARANJEIRA 20 RENATO BRAZ 48 RENATO TEIXEIRA 75 MILTINHO EDILBERTO 100 GERMANO MATHIAS 21 MÔNICA SALMASO 49 PAIXÃO CÔRTES 76 PAULO FREIRE 101 PAULO BELLINATI 22 CONSUELO DE PAULA 50 LUIZ CARLOS BORGES 76 ARTHUR NESTROVSKI 102 TONINHO FERRAGUTTI 23 DÉRCIO MARQUES 51 RENATO BORGHETTI 78 JÚLIO MEDAGLIA 103 CHICO MARANHÃO 24 SUZANA SALLES 52 TANGOS &TRAGEDIAS 78 SANTANNA, O Cantador 104 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) PAPETE 25 NÁ OZETTI 52 ROBSON MIGUEL 79 FAGNER 105 (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil) ANASTÁCIA 26 ELZA SOARES 53 JORGE MAUTNER 80 OSWALDO MONTENEGRO 106 Refalo, Pierre Yves Retratos da música brasileira : 14 anos no palco AMELINHA 26 DELCIO CARVALHO 54 RICARDO HERZ 80 VÂNIA BASTOS 106 do programa Sr. -

A Trajetória De José Penalva Anna Stella Schic Entrevista Darius

REVISTA QUADRIMESTRAL DA ACADEMIA BRASILEIRA DE MÚSICA IACAFTIA BRASILEIRA • DE IC) A Trajetória de José Penalva Saudades de Mário Tavares Anna Stella Schic entrevista Reavaliando o Romantismo Darius Milhaud Musical Brasileiro Saudações a Ilza Nogueira e Atividades da ABM em 2002 Lutero Rodrigues Ácadernia (Brasileira de Música 'Desc(e 1945 a serviço da música no Brasil- Diretoria: 1 ‘hno baieger 1 iiiesidenie), Nlereedes Beis Pequeno (vice-presidente), Roberto Duarte 11 " secretario), Jocy de Oliveira `2" seuetarm 1 ir .u du 1aeuehian t1" . 1 Haiti Aguiar (2 tesoureira; Comissão de contas: Titulares: Amaral Vieira. Aylton Escobar e \,'asco Nlarii. Suplentes: 1.rost Mahle e orton Nlorozowiet. (ladeira Patrono Fundador Sucessores 1. José de Anchieta Heitor Villa-Lobos Ademar Nobrega - Marlos Nobre 9, Luiz Álvares Pinto Fructuoso Vianna Waldemar Henrique - Vicente Salles 3. Domingos Caldas Barbosa J'ayme Ovalle e Radamés Gnattali Bidu Sazão - Cecilia Conde 4. J. J. E. Lobo de Mesquita Oneyda Alvarenga Ernani Aguiar 5. José Mauricio Nunes Garcia Fr. Pedro Sinzig Pe. João Batista Lehmann - Cleofe P. de Mattos - Roberto Tibiriçá 6. Sigismund Neukomm Garcia de Miranda Neto Ernst Mahle 7. Francisco Manuel da Silva Martin Braunwieser Mercedes Reis Pequeno 8, Dom Pedro 1 Luis Cosme José Siqueira - Arnaldo Senise 9. Thomáz Cantuária Paulino Chaves Brasílio Itiberê - Osvaldo Lacerda 10. Cândido lgnácio da Silva Octavio Maul Armando Albuquerque - Régis Duprat 11. Domingos R. Mussurunga Savino de Benedictis Mário Ficarelli 12. José Maria Xavier Otavio Bevilacqua José Maria Neves - 13. José Amat Paulo Silva e Andrade Muricy Ronaldo Miranda 14. Elias Álvares Lobo Dinorá de Carvalho Eudoxia de Barros 15. -

ZÉ DO CAIXÃO: SURREALISMO E HORROR CAIPIRA Ana Carolina

ZÉ DO CAIXÃO: SURREALISMO E HORROR CAIPIRA Ana Carolina Acom — Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná UNIOESTE 29 Denise Rosana da Silva Moraes Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná — UNIOESTE Resumo: Esta pesquisa apresentará como o personagem Zé do Caixão, criado por José Mojica Marins, traduz um imaginário de medos e crenças tipicamente nacionais. Figura típica do cinema brasileiro, ele criou um personagem aterrorizante: a imagem agourenta do agente funerário, que traja-se todo em preto. Distante de personagens do horror clássico, que pouco possuem referências com a cultura latino-americana, Zé do Caixão parece vir diretamente do imaginário ―caipira‖ e temente ao sobrenatural, sempre relacionado ao receio de cemitérios, datas ou rituais religiosos. O estudo parte de conceitos vinculados à cultura e cotidiano, presente em autores como Raymond Williams e Michel de Certeau, para pensarmos de que forma o imaginário popular e a própria cultura são transpostos à tela. Com isso, a leitura cinematográfica, perpassa pelo conceito de imagem-sonho citado por Gilles Deleuze, e intrinsecamente ligado à matéria surrealista. Pensar o cinema de horror através do surrealismo é trazer imagens perturbadoras, muitas vezes oníricas de violência e fantasia. Nesse sentido, temos cenas na trilogia de Zé do Caixão povoadas de alucinações, cores, sonhos e olhos, só comparadas à Buñuel, Jodorowsky, Argento ou Lynch. No entanto, o personagem é um sádico e cético no limiar entre a sóbria realidade e a perplexidade de um sobrenatural que se concretiza em estados anômalos. Palavras-chave: Zé do Caixão; Cultura; Imagem-sonho; Surrealismo Cinema de Horror Brasileiro ou Notas sobre Cultura Popular [...] vi num sonho um vulto me arrastando para um cemitério. -

BAM Presents Brazilian Superstar Marisa Monte in Concert, May 1 & 2

BAM presents Brazilian superstar Marisa Monte in concert, May 1 & 2 SAMBA NOISE Marisa Monte With special guests Arto Lindsay, Seu Jorge, and more TBA BAM Howard Gilman Opera House (30 Lafayette Ave) May 1 & 2 at 8pm Tickets start at $35 April 8, 2015/Brooklyn, NY—Renowned Brazilian singer/songwriter Marisa Monte makes her BAM debut with two nights of contemporary Brazilian popular music in a show specifically conceived for the BAM Howard Gilman Opera House. The performances feature Monte’s hand-picked band and guest artists. Praised by The New York Times as possessing “one of the most exquisite voices in Brazilian music,” Marisa Monte has been the benchmark for excellence among female singers in Brazil since she burst upon the scene in 1987. As she approaches the 30-year mark of her career, she still commands the same admiration and prestige that greeted her stunning debut. Her 12 CDs and seven DVDs have sold over 10 million copies worldwide and garnered 11 Latin Grammy Award nominations (winning four) and eight Video Music Brazil awards. For her BAM debut, she will perform with artists that are closely associated with her, including American producer/composer Arto Lindsay, Brazilian singer/songwriter/actor Seu Jorge, and others to be announced. About the Artists Born in Rio de Janeiro, the home of samba, Marisa Monte honed her singing skills with operatic training in in Italy. Her work embraces the traditions of MPB (música popular brasileira) and samba within a pop format that is modern and sophisticated. Aside from being a talented composer—she recorded her own work starting with her second album, Mais (EMI-Odeon, 1991), produced by Arto Lindsay—Monte is considered one of the most versatile performers in Brazil. -

“Brazil, Show Your Face!”: AIDS, Homosexuality, and Art in Post-Dictatorship Brazil1

“Brazil, Show Your Face!”: AIDS, Homosexuality, and Art in Post-Dictatorship Brazil1 By Caroline C. Landau Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the Department of History at Brown University Thesis Advisor: James N. Green April 14, 2009 1 Cazuza, “Brasil,” Ideologia, Universal Music Group, 1988. My translation Acknowledgements Writing this thesis would not have been possible without the help, guidance, and support of many people. While in Brazil, I had the tremendous pleasure of getting to know the archivists at Associação Brasileira Interdisciplinar de AIDS (ABIA) in Rio de Janeiro, particularly Aline Lopes and Heloísa Souto, without whose help, patience, enthusiasm, goodwill, suggestions, and encyclopedic knowledge of AIDS in Brazil this thesis would never have come to fruition. Thank you also to Veriano Terto, Jr. from ABIA for agreeing to speak with me about AIDS grassroots organization in an interview in the fall of 2007. I am grateful to Dr. Vânia Mercer, who served as a sounding board for many of my questions and a font of sources on AIDS in Brazil in the early 1990s and presently. Thank you to Patricia Figueroa, who taught me the ins-and-outs of the Brown University library system early on in the research of this thesis. Thank you also to the Brown University Department of History for the stipend granted to thesis writers. Part of my research is owed to serendipity and luck. I count as one of my blessings the opportunity to have met Jacqueline Cantore, a longtime friend of Caio Fernando Abreu’s and former MTV executive in Brazil. -

Rádio Nacional Fm De Brasília

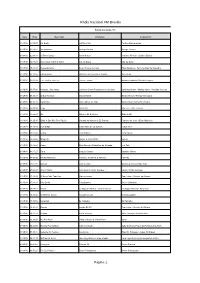

Rádio Nacional FM Brasília RÁDIO NACIONAL FM Data Hora Descrição Intérprete Compositor 01/09/16 00:02:27 For Emily Luiz Eça Trio Pacífico Mascarenhas 01/09/16 01:56:02 Ser Brasileiro George Durand George Durand 01/09/16 02:54:31 A Última Dança Paula Nunes Vanessa Pinheiro / Lidiana Enéias 01/09/16 04:01:21 Uma Gaita Sobre O Morro Edu da Gaita Edu da Gaita 01/09/16 05:00:26 Pressentimento Grupo Toque de Salto Elton Medeiros / Hermínio Belo de Carvalho 01/09/16 06:00:56 Fita Amarela Martinho da Vila & Aline Calixto Noel Rosa 01/09/16 06:03:38 Tim Tim Por Tim Tim Leonel Laterza Haroldo Barbosa / Geraldo Jaques 01/09/16 06:07:43 Verdade, Uma Ilusão Carlinhos Brown/Paralamas do Sucesso Carlinhos Brown / Marisa Monte / Arnaldo Antunes 01/09/16 06:11:31 O Que Se Quer Marisa Monte Marisa Monte / Rodrigo Amarante 01/09/16 06:14:12 Geraldofla Mário Adnet & Lobão Mário Adnet / Bernardo Vilhena 01/09/16 06:18:14 Pagu Maria Rita Rita Lee / Zélia Duncan 01/09/16 06:22:27 Ela Gilberto Gil & Moska Gilberto Gil 01/09/16 06:25:16 Onde A Dor Não Tem Razão Mariana de Moraes & Zé Renato Paulinho da Viola / Elton Medeiros 01/09/16 06:29:06 Dois Cafés Tulipa Ruiz & Lulu Santos Tulipa Ruiz 01/09/16 06:32:46 Lenha Zeca Baleiro Zeca Baleiro 01/09/16 06:36:42 Milagreiro Djavan & Cássia Eller Djavan 01/09/16 06:42:26 Capitu Zélia Duncan & Hamilton de Holanda Luiz Tatit 01/09/16 06:47:27 Terra Caetano Veloso Caetano Veloso 01/09/16 06:53:55 Pavão Misterioso Ednardo, Amelinha & Belchior Ednardo 01/09/16 06:57:56 Estrelar Marcos Valle Marcos & Paulo Sérgio Valle 01/09/16 -

PROJETO DE DECRETO LEGISLATIVO N.º 478, DE 2020 (Do Sr

CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS PROJETO DE DECRETO LEGISLATIVO N.º 478, DE 2020 (Do Sr. José Guimarães) Susta a Portaria nº 189 de 10 de novembro de 2020, que Estabelece as diretrizes para a seleção das personalidades notáveis negras, nacionais ou estrangeiras, a serem divulgadas no sítio eletrônico da Fundação Cultural Palmares DESPACHO: ÀS COMISSÕES DE: CULTURA E CONSTITUIÇÃO E JUSTIÇA E DE CIDADANIA (MÉRITO E ART. 54, RICD) APRECIAÇÃO: Proposição Sujeita à Apreciação do Plenário PUBLICAÇÃO INICIAL Art. 137, caput - RICD Coordenação de Comissões Permanentes - DECOM - P_6748 CONFERE COM O ORIGINAL AUTENTICADO 2 O Congresso Nacional decreta: Art. 1º Fica sustada, nos termos do art. 49, inciso V, da Constituição Federal, a Portaria nº 189 de 10 de novembro de 2020, que Estabelece as diretrizes para a seleção das personalidades notáveis negras, nacionais ou estrangeiras, a serem divulgadas no sítio eletrônico da Fundação Cultural Palmares. Art. 2º Este Decreto Legislativo entra em vigor na data de sua publicação. JUSTIFICAÇÃO O Projeto de Decreto Legislativo ora apresentado pretende sustar a Portaria nº 189 de 10 de novembro de 2020, que Estabelece as diretrizes para a seleção das personalidades notáveis negras, nacionais ou estrangeiras, a serem divulgadas no sítio eletrônico da Fundação Cultural Palmares. Vê-se mais uma vez que tal procedimento visa atender setores fascistas e faz parte de um conjunto de "politicagem" deste governo. Ora afirmar que a lista passará a fazer apenas homenagens póstumas, ou seja, vai conter somente nomes de personalidades já mortas. Em uma rede social Sérgio Camargo, presidente da Fundação Palmares informou que no dia 1º de dezembro vai comunicar todas as exclusões e inclusões na lista. -

I Knew That Music Was My Language, That Music Would Take Me to See the World, Would Take Me to Other Lands

"I knew that music was my language, that music would take me to see the world, would take me to other lands. For I thought there was the music of the earth and the music from heaven." Gil, about his childhood in the city where he lived, in Bahia, where he used to race to the first clarinet sound of the band, which started the religious celebrations, and seemed to invade everything. His career began with the accordion, still in the 50s, inspired by Luiz Gonzaga, the sound of the radio and the religious parades in town. Within the Northeast he explored a folk country sound, until Joao Gilberto emerges, the bossa nova, as well as Dorival Caymmi, with its coastal beach sound, so different from that world of wilderness he was used to. Influenced, Gil leaves aside the accordion and holds the guitar, then the electric guitar, which harbors the particular harmonies of his work until today. Since his early songs he portrayed his country, and his musicianship took very personal rhythmic and melodic forms. His first LP, “Louvação” (Worship) , released in 1967, concentrated his particular ways of translating regional components into music, as seen in the renown songs Louvação, Procissão, Roda and Viramundo. In 1963 after meeting his friend Caetano Veloso at the University of Bahia, Gil begins with Caetano a partnership and a movement that contemplated and internationalized music, theater, visual arts, cinema and all of Brazilian art. The so-called Tropicália or Tropicalist movement, involves talented and plural artists such as Gal Costa, Tom Ze, Duprat, José Capinam, Torquato Neto, Rogério Duarte, Nara Leão and others. -

Dulcinéia Catadora: Cardboard Corporeality and Collective Art in Brazil

Vol. 15, Num. 3 (Spring 2018): 240-268 Dulcinéia Catadora: Cardboard Corporeality and Collective Art in Brazil Elizabeth Gray Brown University Eloísa Cartonera and Cardboard Networks From a long history of alternative publishing in Latin America, Eloísa Cartonera emerged in Argentina in 2003, and sparked a movement that has spread throughout South and Central America and on to Africa and Europe. The first cartonera emerged as a response to the debt crisis in Argentina in 2001 when the country defaulted causing the Argentine peso to plummet to a third of its value. Seemingly overnight, half of the country fell into living conditions below the poverty line, and many turned to informal work in order to survive. The cartoneros, people who make their living salvaging and reselling recyclable materials, became increasingly present in the streets of Buenos Aires. With the onset of neoliberal policies, people mistrusted and rejected everything tied to the government and economic powers and saw the need to build new societal, political, and cultural models. Two such people were the Argentine poet, Washington Cucurto, and artist Javier Barilaro. Distressed by the rising number of cartoneros and the impossible conditions of the publishing market, Cucurto and Barilaro founded Eloísa Cartonera. Thirteen years later, Eloísa is still printing poetry and prose on Xeroxed paper and binding it in cardboard bought from cartoneros at five times the rate of the recycling Gray 241 centers. The cardboard covers are hand-painted in tempera by community members, including cartoneros, and then sold on the streets for a minimal price, just enough to cover production costs. -

A Autora Paulistana Lygia Fagundes

ASPECTOS DA VIOLÊNCIA EM AS MENINAS, DE LYGIA FAGUNDES TELLES Sandrine Robadey Huback (UFMT) Resumo: Em As meninas (1973), tanto a enunciação da autora quanto o enredo da narrativa encontram-se contextualizados em um ambiente opressor, marcado pelo silenciamento das alteridades. Lygia Fagundes Telles alinha a vida conturbada das três jovens, personagens principais do romance, ao meio externo assinalado, sendo este mesmo meio uma das molas propulsoras do processo imaginativo da autora. Observando que a violência é o elemento recorrente na vida das meninas, analisamos como essa temática devém elemento estruturante da obra (em diálogo com o seu contexto de publicação), a qual pode apresentar-se como um estímulo à reflexão contemporânea de nossa memória histórica e cultural. Palavras-chave: Literatura; História; Violência; Memória. A autora paulistana Lygia Fagundes Telles, quando questionada acerca da função social de seu ofício, afirma que o papel do escritor é “ser testemunha do seu tempo e da sua sociedade, testemunha e participante”. Assim, partindo de tal declaração, refletimos acerca do alcance de sua obra As meninas, publicada em 1973, durante a fase política ditatorial de intensificação da suspensão da liberdade e do abuso de poder. O romance, complexo e pulsante, revela aos leitores o universo particular de três personagens femininas que moram no pensionato católico Nossa Senhora de Fátima. “A época é o ano de 1969, indicado indiretamente pela referência ao célebre sequestro do embaixador americano Charles Elbrick” (TEZZA apud TELLES, 2009, p. 288). Conforme Cristovão Tezza (2009), o contexto histórico do lançamento do romance é o Brasil “jurássico”, onde ainda prevaleciam os valores individuais pequeno- burgueses, em meio ao aparecimento de movimentos sociais e culturais que contestavam a ordem tradicional vigente.