Detailed Social and Gender Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar M AY 2014 Above: Behsud Bridge, Nangarhar Province (Photo by TLO) A TLO M A P P I N G R EPORT Justice and Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar May 2014 In Cooperation with: © 2014, The Liaison Office. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, The Liaison Office. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report was commissioned from The Liaison Office (TLO) by Cordaid’s Security and Justice Business Unit. Research was conducted via cooperation between the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC) and TLO, under the supervision and lead of the latter. Cordaid was involved in the development of the research tools and also conducted capacity building by providing trainings to the researchers on the research methodology. While TLO makes all efforts to review and verify field data prior to publication, some factual inaccuracies may still remain. TLO and AWRC are solely responsible for possible inaccuracies in the information presented. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The Liaison Office (TL0) The Liaison Office (TLO) is an independent Afghan non-governmental organization established in 2003 seeking to improve local governance, stability and security through systematic and institutionalized engagement with customary structures, local communities, and civil society groups. -

CB Meeting PAK/AFG

Polio Eradication Initiative Afghanistan Current Situation of Polio Eradication in Afghanistan Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 29-30 April 2015,Abu Dhabi AFP cases Classification, Afghanistan Year 2013 2014 2015 Reported AFP 1897 2,421 867 cases Confirmed 14 28 1 Compatible 4 6 0 VDPV2 3 0 0 Discarded 1876 2,387 717 Pending 0 0 *149 Total of 2,421 AFP cases reported in 2014 and 28 among them were confirmed Polio while 6 labelled* 123as Adequatecompatible AFP cases Poliopending lab results 26 Inadequate AFP cases pending ERC 21There Apr 2015 is one Polio case reported in 2015 as of 21 April 2015. Region wise Wild Poliovirus Cases 2013-2014-2015, Afghanistan Confirmed cases Region 2013 2014 2015 Central 1 0 0 East 12 6 0 2013 South east 0 4 0 Districts= 10 WPV=14 South 1 17 1 North 0 0 0 Northeast 0 0 0 West 0 1 0 Polio cases increased by 100% in 2014 Country 14 28 1 compared to 2013. Infected districts increased 2014 District= 19 from 10 to 19 in 2014. WPV=28 28 There30 is a case surge in Southern Region while the 25Eastern Region halved the number of cases20 in comparison14 to 2013 Most15 of the infected districts were in South, East10 and South East region in 2014. No of AFP cases AFP of No 1 2015 5 Helmand province reported a case in 2015 District= 01 WPV=01 after0 a period of almost two months indicates 13 14 15 Year 21continuation Apr 2015 of low level circulation. Non Infected Districts Infected Districts Characteristics of polio cases 2014, Afghanistan • All the cases are of WPV1 type, 17/28 (60%) cases are reported from Southern region( Kandahar-13, Helmand-02, and 1 each from Uruzgan and Zabul Province). -

Mohmad Agency Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL FATA (MOHMAND AGENCY) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH MOHMAND AGENCY 466,984 48,118 AMBAR UTMAN KHEL TEHSIL 62,109 6,799 AMBAR UTMAN KHEL TRIBE 62,109 6799 BAZEED KOR SECTION 21,174 2428 BAHADAR KOR 4,794 488 082050106 695 50 082050107 515 54 082050108 256 33 082050109 643 65 082050110 226 35 082050111 326 39 082050112 425 55 082050113 837 64 082050114 192 24 082050115 679 69 BAZID KOR 8,226 943 082050116 689 71 082050117 979 80 082050118 469 45 082050119 1,062 128 082050120 1,107 145 082050121 655 72 082050122 845 123 082050123 1,094 111 082050124 455 60 082050125 871 108 ISA KOR 3,859 490 082050126 753 93 082050127 1,028 104 082050128 947 118 082050129 715 106 082050130 416 69 KOT MAINGAN 673 79 082050105 673 79 WALI BEG 3,622 428 082050101 401 49 082050102 690 71 082050103 1,414 157 082050104 1,117 151 MAIN GAN SECTION 40,935 4371 AKU KOR 5,478 583 082050223 1,304 117 082050224 154 32 082050225 490 41 082050226 413 40 082050227 1,129 106 082050228 1,988 247 BANE KOR 8,626 1012 Page 1 of 12 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL FATA (MOHMAND AGENCY) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 082050214 1,208 121 082050215 1,363 141 082050216 672 67 082050217 901 99 082050218 1,117 175 082050219 1,507 174 082050220 448 76 082050221 839 79 082050222 571 80 KHORWANDE 1,907 184 082050229 1,714 159 082050230 193 25 MAIN GAN 11,832 1182 082050201 1,209 114 082050202 1,105 124 082050203 1,322 128 082050204 1,387 138 082050205 1,043 75 082050206 774 71 082050207 763 75 082050208 -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

Afridi Tribe

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Center on Contemporary Conflict Center for Contemporary Conflict (CCC) Publications 2016 Afridi Tribe Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/49867 Program for Culture and Conflict Studies AFRIDI TRIBE The Program for Culture & Conflict Studies Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, CA Material contained herein is made available for the purpose of peer review and discussion and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. PRIMARY LOCATION Khyber Agency, Peshawar District MAJOR TOWNS The headquarters for the Political Agent is in Peshawar, but Assistant Political Agents may be found in Bara, Jamrud, and Landi Kotal. There is also a government presence (Customs house) at Torkham on the Durand Line. TERRAIN AND CLIMATE TERRAIN FATA is situated between the latitudes of 31° and 35° North, and the longitudes of 69° 15' and 71° 50' East, stretching for maximum length of approximately 450 kilometers and spanning more than 250 kilometers at its widest point. Spread over a reported area of 27,220 square kilometers, it is bounded on the north by the district of Lower Dir in the NWFP, and on the east by the NWFP districts of Bannu, Charsadda, Dera Ismail Khan, Karak, Kohat, Lakki Marwat, Malakand, Nowshera and Peshawar. On the south-east, FATA joins the district of Dera Ghazi Khan in the Punjab province, while the Musa Khel and Zhob districts of Balochistan are situated to the south. -

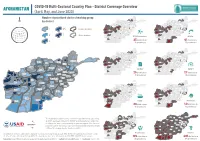

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Medicinal Plants Used Traditionally in Guldara District of Kabul, Afghanistan

International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Chinese Medicine ISSN: 2576-4772 Medicinal Plants Used Traditionally in Guldara District of Kabul, Afghanistan 1 2 Amini MH * and Hamdam SM Research Article 1Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Kabul University, Volume 1 Issue 3 Afghanistan Received Date: October 09, 2017 Published Date: November 06, 2017 2Fifth year student, Faculty of Pharmacy, Kabul University, Afghanistan *Corresponding author: Amini MH, Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Kabul University, Jamal mina, Kabul, Afghanistan, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Medicinal plants are traditionally used in different parts of Afghanistan since long back. Guldara is one of the districts of Kabul province where numerous plants are traditionally used in treatment of a wide range of routine diseases such as; gastrointestinal disorders, urinary tract infections, respiratory problems, skin diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and so on. But, published records of folk and traditional health approaches practiced in Guldara as well as other parts of Afghanistan are still very scarce. Ethnopharmacological field studies not only contribute in the public health domain but also serve as the basis for further pharmaceutical and medical researchers. In such context, present field study aims to record the plant crude drugs used traditionally in eight villages of Guldara district. Data were collected through questionnaires replied by local healers or Hakims, experienced elder individuals and patients using herbal crude drugs. Botanical name, family, common Dari/Pushto names, parts used, preparations and administration route, and indications of total 68 plants belonging to 30 families, and used by Guldara residents are reported in this paper. Herbarium specimens of 20 species were also prepared, and after being authenticated, were deposited in herbarium of Pharmacy faculty, Kabul University, for further use. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Report 2013–1124

Prepared in cooperation with the Afghan Geological Survey under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Task Force for Business and Stability Operations Topographic and Hydrographic GIS Datasets for the Afghan Geological Survey and U.S. Geological Survey 2013 Mineral Areas of Interest Open-File Report 2013–1124 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photo showing mountainous terrain and the alluvial floodplain of a small tributary in the upper reaches of the Kabul River Basin located northeast of Kabul Afghanistan, 2004 (Photograph by Peter G. Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey). Topographic and Hydrographic GIS Datasets for the Afghan Geological Survey and U.S. Geological Survey 2013 Mineral Areas of Interest By Brittany N. Casey and Peter G. Chirico Open-File Report 2013–1124 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2013 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Nuristan (Kafiristan) and the Kalash Kafirs of Chitral Part One

Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab Bind 41, nr. 3 Hist. Filos. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. 41, no. 3 (1966) AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NURISTAN (KAFIRISTAN) AND THE KALASH KAFIRS OF CHITRAL PART ONE SCHUYLER JONES With a Map by Lennart Edelberg København 1966 Kommissionær: Munksgaard X Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab udgiver følgende publikationsrækker: The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters issues the following series of publications: Bibliographical Abbreviation. Oversigt over Selskabets Virksomhed (8°) Overs. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Annual in Danish) Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser (8°) Hist. Filos. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter (4°) Hist. Filos. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (History, Philology, Philosophy, Archeology, Art History) Matematisk-fysiske Meddelelser (8°) Mat. Fys. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. Matematisk-fysiske Skrifter (4°) Mat. Fys. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Astronomy, Geology) Biologiske Meddelelser (8°) Biol. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. Biologiske Skrifter (4°) Biol. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Botany, Zoology, General Biology) Selskabets sekretariat og postadresse: Dantes Plads 5, København V. The address of the secretariate of the Academy is: Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Dantes Plads 5, Köbenhavn V, Denmark. Selskabets kommissionær: Munksgaard’s Forlag, Prags Boulevard 47, København S. The publications are sold by the agent of the Academy: Munksgaard, Publishers, 47 Prags Boulevard, Köbenhavn S, Denmark. HISTORI SK-FILOSO FISKE MEDDELELSER UDGIVET AF DET KGL. DANSKE VIDENSKABERNES SELSKAB BIND 41 KØBENHAVN KOMMISSIONÆR: MUNKSGAARD 1965—66 INDHOLD Side 1. H jelholt, H olger: British Mediation in the Danish-German Conflict 1848-1850. Part One. From the MarCh Revolution to the November Government. -

Great Game to 9/11

Air Force Engaging the World Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland COVER Aerial view of a village in Farah Province, Afghanistan. Photo (2009) by MSst. Tracy L. DeMarco, USAF. Department of Defense. Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland Washington, D.C. 2014 ENGAGING THE WORLD The ENGAGING THE WORLD series focuses on U.S. involvement around the globe, primarily in the post-Cold War period. It includes peacekeeping and humanitarian missions as well as Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom—all missions in which the U.S. Air Force has been integrally involved. It will also document developments within the Air Force and the Department of Defense. GREAT GAME TO 9/11 GREAT GAME TO 9/11 was initially begun as an introduction for a larger work on U.S./coalition involvement in Afghanistan. It provides essential information for an understanding of how this isolated country has, over centuries, become a battleground for world powers. Although an overview, this study draws on primary- source material to present a detailed examination of U.S.-Afghan relations prior to Operation Enduring Freedom. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. Cleared for public release. Contents INTRODUCTION The Razor’s Edge 1 ONE Origins of the Afghan State, the Great Game, and Afghan Nationalism 5 TWO Stasis and Modernization 15 THREE Early Relations with the United States 27 FOUR Afghanistan’s Soviet Shift and the U.S.