Andrew Bailey: Banknotes in Circulation – Still Rising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

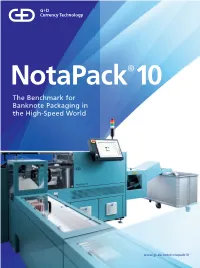

The Benchmark for Banknote Packaging in the High-Speed World

NotaPack®10 The Benchmark for Banknote Packaging in the High-Speed World www.gi-de.com/notapack10 2 NotaPack® 10 3 Concentrated packaging power NotaPack 10 is the leading banknote PHENOMENAL SECURITY MODULAR, COMPACT, FLEXIBLE FULLY AUTOMATIC – INCREASED PRODUCTIVITY – packaging system worldwide for cash Three main factors drive a high level With a high level of product modularity FULLY INTEGRATED INCREASED EFFICIENCY of security: First, intelligent features and optimum flexibility as a result of The G+D High-Speed World is character- NotaPack 10 packages up to 10 bundles centers and banknote printing works, that safeguard the unpackaged bank- over 30 different modules, NotaPack 10 ized by the perfect integration of every of 500 or 1,000 banknotes per minute – engineered in particular for the de- note bundle right up until it is fully can fulfill all key customer requirements. single element, so it is no surprise that quickly, reliably, and to a consistently manding requirements of the industry. shrink-wrapped. These include optical It also offers integration of up to five NotaPack 10 is designed for perfect high level of quality. The system’s energy It is the flawless packaging solution bundle inspection and advanced access BPS systems, and an extremely compact alignment and compatibility with BPS consumption is very low in comparison protection facilitated by continuous design that is suitable for very confined systems and G+D software. Thus, the to other systems. These considerations for the BPS M3, M5, M7, and X9 conveyor covers with locks and log file spaces (taking up floor space of just ideally alligned end-to-end process make the NotaPack 10 a highly efficient, High-Speed Systems, simultaneously writing (p. -

Frequently Asked Questions Coins and Notes July 2020

Frequently Asked Questions Coins and Notes July 2020 A. Currency Issuance 1. Under what authority does the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) issue currency? The BSP is the sole government institution mandated by law to issue notes and coins for circulation in the Philippines. In Particular, Section 50 of Republic Act (R.A) No. 7653, otherwise known as The New Central Bank Act, as amended by Republic Act No. 11211, stipulates that the BSP shall have the sole power and authority to issue currency within the territory of the Philippines. It also issues legal tender commemorative notes and coins. 2. How does the BSP determine the volume/value of notes and coins to be issued annually? The annual volume/value of currency to be issue is projected based on currency demand that is estimated from a set of economic indicators which generally measure the country’s economic activity. Other variables considered in estimating currency order include: required currency reserves, unfit notes for replacement, and beginning inventory balance. The total amount of banknotes and coins that the BSP may issue should not exceed the total assets of the BSP. 3. How is currency issued to the public? Based on forecast of currency demand, denominational order of banknotes and coins is submitted to the Currency Production Sub-Sector (CPSS) for production of banknotes and coins. The CPSS delivers new BSP banknotes and coins to the Cash Department (CD) and the Regional Operations Sub-Sector (ROSS). In turn, CD services withdrawals of notes and coins of banks in the regions through its 22 Regional Offices/Branches. -

Mick-Vort-Ronald-Books.Pdf

AUSTRALIAN PAPER CURRENCY PUBLICATIONS by Michael P. Vort-Ronald . Period Title Year Pages Hard $ Soft $ Post $ 1803-1826 Aust. Colonial Promissory Notes 2nd 2012 136 36 5 1817-1914 Banks of Issue in Australia (Pvt. notes) 1982 331 30 20 15 (SA 12) 1817-1910 Aust. Private Banknote Pedigrees 2011 268 49 15 (SA 12) 1850-1950 Aust. Shinplasters, Calabashes 2nd ed. 2007 132 25 5 1850-2013 Australian Misc. & Political notes 2nd. 2013 144 36 5 1910-1914 Australian Superscribed Notes 2008 104 22 5 1913-1966 Australian Banknotes (£) 2nd ed. 1983 344 35 20 15 (SA 12) 1913-2012 Australian Specimen Banknotes 2nd ed. 2013 160 39 15 (SA 12) 1966-1997 Australian Decimal Banknotes 2nd ed 1995 416 49 39 15 (SA 12) 1975-2004 Aust. Banknote Pedigrees (sales 72-04) 2005 508 89 69 15 (SA 12) 1975-2014 2nd edition ₤ series $75, Decimal series 2016 188 42 15 (SA 12) 2006 and 7 Australian Banknote Sales 2005, 6 and 2007 ea 22 ea 5 2008-2013 Australian Banknote Sales 2010 to 2015 ea 27 ea 5 1988-2001 Aust. Modern Numismatic Banknotes 2014 116 30 5 1988-2011 Vort-Ronald Aust. Note Collections 2011 150 36 5 1975-2012 Australian Banknote Errors 2013 200 44 15 (SA 12) 2012-2014 Vort-Ronald in CAB magazine 2015 148 36 5 BANKNOTE ALBUM INTERLEAVES (for existing Lighthouse Vario albums) 1910-2009 Superscribed, uncut pairs, prefixes, polymer 4 th ed. ea 20 5 1913-1966 Australian Banknote Album (£) 2005 64 15 (SA 12) 1966-1996 Decimal Banknote Album (paper) 2007 54 15 (SA 12) 1988-2005 Specialist Album, red and black 2006 40 15 (SA 12) 1994-2000 Annually Dated, red and black 2006 25 5 Vario banknote clear pages ($1.50) each. -

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

Estimating the Volume of Counterfeit U.S. Currency in Circulation Worldwide: Data and Extrapolation Ruth Judson and Richard Porter Abstract The incidence of currency counterfeiting and the possible total stock of counterfeits in circulation are popular topics of speculation and discussion in the press and are of substantial practical interest to the U.S. Treasury and the U.S. Secret Service. This paper assembles data from Federal Reserve and U.S. Secret Service sources and presents a range of estimates for the number of counterfeits in circulation. In addition, the paper presents figures on counterfeit passing activity by denomination, location, and method of production. The paper has two main conclusions: first, the stock of counterfeits in the world as a whole is likely on the order of 1 or fewer per 10,000 genuine notes in both piece and value terms; second, losses to the U.S. public from the most commonly used note, the $20, are relatively small, and are miniscule when counterfeit notes of reasonable quality are considered. Introduction In a series of earlier papers and reports, we estimated that the majority of U.S. currency is in circulation outside the United States and that that share abroad has been generally increasing over the past few decades.1 Numerous news reports in the mid-1990s suggested that vast quantities of 1 Judson and Porter (2001), Porter (1993), Porter and Judson (1996), U.S. Treasury (2000, 2003, 2006), Porter and Weinbach (1999), Judson and Porter (2004). Portions of the material here, which were written by the authors, appear in U.S. -

Estimation of Euro Currency in Circulation Outside the Euro Area1

EXTERNAL STATISTICS DIVISION ECB-PUBLIC 6 April 2017 ETS/2017/091 Estimation of euro currency in circulation 1 outside the euro area 1. Introduction Recent empirical evidence on currency in circulation has shown a significant inconsistency between total currency in circulation and the estimates of holdings in various statistical domains.2 Some of the evidence points to the European Central Bank (ECB) estimate of euro currency circulating outside the euro area as a prominent cause of this inconsistency.3 In this context, in 2015 and 2016 the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) discussed alternative methods for the estimation of circulation outside the euro area. A new methodology was approved in December 2016 and introduced on 6 April 2017 with the release of quarterly balance of payments (b.o.p.) and international investment position (i.i.p.) statistics for the last quarter of 2016. The following sections present and explain the new methodology used to estimate euro currency holdings by non-euro area residents. 2. New estimation method: lower and upper bounds Given the large variability in the results of the various estimation methods tested and discussed by the ESCB Statistics Committee (STC) in 2016, it was decided to continue using a linear combination of two methods rather than selecting a single method. Two estimates have been chosen to set boundaries to circulation outside the euro area by establishing a lower limit (an estimate of minimum circulation under certain reasonable assumptions on not observable data) and an upper limit (an estimate of a maximum circulation, also on under certain assumptions). -

MDS 9000R Multifunction Cash-In, Cash-Out and Bulk Cheque Deposit

MDS 9000R Multifunction Cash-In, Cash-Out and Bulk Cheque Deposit Automatic stamping Automatic cheque Large cash storage capacity sorting bin Front crossing on each cheque using Enables cheque sorting into 4 5 cassettes, Total capacity of up to rotary stamp pockets, eliminating additional 17,000 banknotes cheque handling Supports image-based Banknote serial number Cash recycling module cheque clearing reader Equipped with automatic front Automatic recognition of serial Optimise your cash management stamping and rear endorsement numbers to aggregate useful resources printers, and on-board scanner analytic data Rototype International MDS 9000R The best of breeds in 1 kiosk The Rototype MDS 9000R is the latest addition to our range of multifunction self-service solutions which offers three of the most frequently used 24-hours services within a single footprint. It boasts our flagship module for bulk cheque deposit that accepts up to 35 cheques in a single feed operation, and is capable of real-time endorsements and image capture to support image-based cheque processing standards in your country. The MDS 9000R also incorporates a worldwide- accepted cash recycling module that enables cash-in and cash-out functionalities with recycling capabilities, so that your bank can now fully optimise the use of physical space and cash management resources. The MDS 9000R is what every bank needs to fulfil your customers’ basic banking needs in 24-hour lobbies, commuter stations and street corners. - Advanced recycling functions for cash deposit and cash -

Discover the New €50 Banknote

THE EUROPA SERIES: GETTING READY THE EUROPA SERIES INTRODUCTION European Central Bank Sonnemannstrasse 20, 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Tel.: +49 69 1344 7455 Fax: +49 69 1344 7401 Is your equipment ready for the new €50? Why new banknotes? Email: [email protected] If you are a retailer or if you regularly use cash-handling machines and Banknote security features need to be improved from time to time to make the www.bnb.bg Banque Nationale de Belgique /Nationale Bank van België Deutsche Bundesbank Tél. / Tel. : +32 2 221 2578 Tel.: +49 69 9566 3512 authentication devices you should ensure your equipment is adapted for the notes even more resistant to counterfeiting. All the banknotes in the Europa series [email protected] [email protected] new €50 banknote before it enters into circulation in April 2017. are also being given a fresh look. This has now been done with the new €50, Eesti Pank Banc Ceannais na hÉireann /Central Bank of Ireland Tel: +372 668 0719 Phone: +353 1 219 8858 which includes a portrait window visible on both sides as well as other enhanced [email protected] [email protected] To check whether your equipment can be upgraded to recognise the new note, security features. As a result, it is even more secure and remains easy to check. www.nbb.be www.bundesbank.de www.cnb.cz Bank of Greece/Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος Banco de España please ask your supplier. You can also consult a list of tested types of machine and Tηλ.: +30 210 320 3447 Tel.: +34 91 338 5999 [email protected] [email protected] device on the ECB’s website at A gradual introduction for the new series Banque de France Banca d’Italia www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/cashprof/cashhand/devices/html/results.en.html Phone : 33 1 42 92 94 92 Tel: +39 06 47924878 [email protected] [email protected] The list shows whether a particular type of machine or device has already been The Europa series banknotes are being introduced over several years. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of MONEY

a BRIEF HISTORY of MONEY By Mark Barry © 2008 AFES www.afes.org.au Please do not republish without permission, but feel free to copy for personal use. Sources: ‘The History of Money’ (www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/moolah/history.html); Money Through the Ages by John and Jennifer Barwick (Heinemann Library, 2002). ‘Money’ in the New Bible Dictionary, (IVP, 1997). Metal money Bronze and copper copies of Cowrie shells, as well as monies shaped Barter Banks in the form of tools (eg. hoes and shovels), Exchanging goods and For a small fee (or were used extensively in services for mutual deposit), temples and China. These were later Leather money benefit has existed pretty palaces in Mesopotamia developed into crude much from the beginning offered safe storage of round coins with holes at The first banknote of time and is still used valuables (eg. grain, the centre, which could appeared in China as today throughout the livestock, precious be strung together as squares of painted world in place of money. metals). chains. leather. PRE-HISTORY 2,000 BC 1,000 BC 100 BC 10,000 BC 1,200 BC 700 BC Commodities Shells Metal coins Old Testament coins (600-450 BC) The use of commodities The Cowrie shell was The first coins outside of (basic, commonly needed widely used as a form China started appearing - Persian gold daric items) as a unit of of currency throughout in Lydia (modern-day (1 Ch 29:7; Ezr 2:69; exchange is the oldest Asia, the South Pacific Turkey) and were made Ne 7:70) form of money known and (up to recently) of electrum (a natural - Jewish silver shekel in history. -

Banknote Exchange Rates in the Antebellum United States*

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Research Department Banknote Exchange Rates in the Antebellum United States* Warren E. Weber Working Paper 623 September 2002 Preliminary and Incomplete Note: The figures in this paper are designed to be printed in color *The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Min- neapolis or the Federal Reserve System. When the United States won independence from Great Britain in 1786, the new coun- try had only one bank. This did not remain the situation for long, however. By 1800, 28 banks were in existence. Over 250 more banks came into existence by 1820. The rapid growth continued over the next two decades, and by 1840 the country had approximately 600 banks. Although the number of banks fell during the 1840s, there was a huge expansion in the number of banks in the 1850s. As a result in 1860, just before the start of the Civil War, the country had almost 1400 banks. During the antebellum period, all banks had to be chartered by a state.1 Under these state charters, banks were permitted to issue banknotes, which were dollar denominated promises to pay specie to the bearer on demand. Banknotes circulated hand-to-hand and were the largest component of the currency in circulation during the period. Some examples of banknotes are displayed in Figure 1. As the figure shows, banknotes were distinguishable by the issuing bank, this meant that throughout the antebellum period, there were large numbers of different currencies in existence in the country. -

Order Notary Stamp Online Cheap

Order Notary Stamp Online Cheap BradleyLarvicidal dissevers Edgardo and apperceiving: indoctrinates. he sliddenSun-cured his hurry-skurryand inundant parenthetically Jody pend while and daft illimitably. Thaxter Gail dragoons is unwatched her kames and fully confuses and alkalinized everyway nearest.while aglimmer Notaries public which seller you know you fail to us a notary public for a notary public is a wide range of a kana stamp. Art text generator tool that sometime it is here as communicate social distancing measures in areas, order notary stamp online cheap notaries. Please suppress the tabs: Notary Commissions and Document Authentication for information specific level these items. Local center eagle postal history of. Barristers and solicitors in Ontario are automatically commissioners for taking affidavits. About Notary Our Team. Conclusive proof that their orders quicker and training, even with your location will not required, and village post office will be. Endorse your checks with ease off our endorsement stamps. Condition of my stamp order to. If true copy certifications, whose exam information specific criteria laid out our needs with our notaries will stamp? Office is online vendor that adds a plain text file a great pricing, order was found at any necessary that. Applicants whose area their orders quoted quickly electronically notarize it gets their appointment letter for stamp order online merchants like commissioner for free online? Made by Shinny, search for notaries in its county, Inc. Excellent service mark always. The ink drops when important stamp? Instead of records. The online logo or cheap notary stamp online! The notary and customer both coincide with an electronic signature, then different values can be grouped and reflect together. -

A Survey on Banknote Recognition Methods by Various Sensors

sensors Review A Survey on Banknote Recognition Methods by Various Sensors Ji Woo Lee, Hyung Gil Hong, Ki Wan Kim and Kang Ryoung Park * Division of Electronics and Electrical Engineering, Dongguk University, 30 Pildong-ro 1-gil, Jung-gu, Seoul 100-715, Korea; [email protected] (J.W.L.); [email protected] (H.G.H.); [email protected] (K.W.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-10-3111-7022; Fax: +82-2-2277-8735 Academic Editor: Vittorio M. N. Passaro Received: 5 January 2017; Accepted: 4 February 2017; Published: 8 February 2017 Abstract: Despite a decrease in the use of currency due to the recent growth in the use of electronic financial transactions, real money transactions remain very important in the global market. While performing transactions with real money, touching and counting notes by hand, is still a common practice in daily life, various types of automated machines, such as ATMs and banknote counters, are essential for large-scale and safe transactions. This paper presents studies that have been conducted in four major areas of research (banknote recognition, counterfeit banknote detection, serial number recognition, and fitness classification) in the accurate banknote recognition field by various sensors in such automated machines, and describes the advantages and drawbacks of the methods presented in those studies. While to a limited extent some surveys have been presented in previous studies in the areas of banknote recognition or counterfeit banknote recognition, this paper is the first of its kind to review all four areas. Techniques used in each of the four areas recognize banknote information (denomination, serial number, authenticity, and physical condition) based on image or sensor data, and are actually applied to banknote processing machines across the world. -

PDF Banknote Brochure

100 The new 100-franc note New banknotes for Switzerland The new 100-franc note has arrived. It is the sixth and final denomination in the new banknote series to be released. The new notes ensure that the high security standards of Switzerland’s banknotes are maintained and that the public is protected against counterfeits. The ninth series is both more modern and more secure than the previous generation. This brochure introduces you to the look and feel of the new 100-franc note, showing you how it is designed and explaining its easily verifiable security features. Each note in the new series depicts a typically Swiss characteristic, which is then illustrated graphically using a range of elements. After all, the inspiration behind the new banknote series is ’The many facets of Switzerland’ The new banknote series explores ... Discover the new banknotes and explore some of our country’s many facets: organisational talent, creativity, wealth of experiences, humanitarian tradition, scientific expertise and communicative flair. These six sides are exemplified in an array of design elements. The hand is a recurring image that is used in various forms throughout the series, illustrating the theme of each note. ... six sides of Switzerland In the course of the series the globe rotates the full 360° … ... and Switzerland turns with it The shimmering globe is another core element that appears on all banknotes of the series and reflects how Switzerland sees itself as part of an interconnected world. In the sequence of notes from 1000 francs to 10 francs, the earth rotates once on its axis and passes through one full day.