The Priestly Noachic Polemics in 2 Enoch and the Epistle to the Hebrews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mortality Fan Charts

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Dowd, Kevin; Blake, David; Cairns, Andrew J. G. Article The myth of Methuselah and the uncertainty of death: The mortality fan charts Risks Provided in Cooperation with: MDPI – Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, Basel Suggested Citation: Dowd, Kevin; Blake, David; Cairns, Andrew J. G. (2016) : The myth of Methuselah and the uncertainty of death: The mortality fan charts, Risks, ISSN 2227-9091, MDPI, Basel, Vol. 4, Iss. 3, pp. 1-7, http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/risks4030021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/167889 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu risks Article The Myth of Methuselah and the Uncertainty of Death: The Mortality Fan Charts Kevin Dowd 1,*, David Blake 2 and Andrew J. -

The Generations of Adam

The Generations of Adam hat is the purpose of Bible chronology? According to Philip Mauro, in Wonders of Bible Chronology, “its basis is the Bible itself; its plan is the genealogical or life line that Wstretches from the first Adam to the last Adam ... and its purpose is to bring those who follow its progress to revelations of vital truth pertaining to God’s mighty work of redemption.” Genesis 5 reveals the time span between Adam and the worldwide flood of Noah’s time. The following table summarizes this time line: Age at: Anno Hominis Adam created 0 Adam's birth of Seth (130) 130 Seth's birth of Enosh (105) 235 Enosh's birth of Kenan (90) 325 Kenan's birth of Mahalalel (70) 395 Mahalalel's birth of Jared (65) 460 Jared's birth of Enoch (162) 622 Enoch's birth of Methuselah (65) 687 Methuselah's birth of Lamech (187) 874 Lamech's birth of Noah (182) 1056 time of worldwide flood Noah's 1656 (600) Before we analyze Genesis 5 further, a few general points must be made. First, the Bible is the only reliable source book that gives history with an exact chronology for the first 4000 years of the human race. It has been about 6000 years since the creation of man. For the first 3/5ths of this period, there is no chronological information whatever except in the Bible. The histories of other peoples give an account of their beginning vaguely and in the context of myths and fables. In contrast, the Bible is a very accurate historical document. -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 4 Number 1 Article 52 1992 The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture Michael D. Rhodes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Rhodes, Michael D. (1992) "The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 52. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol4/iss1/52 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture Author(s) Michael D. Rhodes Reference Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 4/1 (1992): 120–26. ISSN 1050-7930 (print), 2168-3719 (online) Abstract Review of . By His Own Hand upon Papyrus: A New Look at the Joseph Smith Papyri (1992), by Charles M. Larson. Charles M. Larson, ••. By His Own Hand upon Papyrus: A New Look at the Joseph Smith Papyri. Grand Rapids: Institute for Religious Research, 1992. 240 pp., illustrated. $11.95. The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture Reviewed by Michael D. Rhodes The book of Abraham in the Pearl of Great Price periodically comes under criticism by non-Monnons as a prime example of Joseph Smith's inability to translate ancient documents. The argument runs as follows: (1) We now have the papyri which Joseph Smith used to translate the book of Abraham (these are three of the papyri discovered in 1967 in the Metropolitan Museum of An in New York and subsequently turned over to the Church; the papyri in question are Joseph Smith Papyri I. -

The Christian Comforter

The Christian Comforter Enoch the seventh from Adam In the book of Genesis, there are two Enoch’s; one from the line of Cain, in Genesis 4:17, and one from the line of Seth, who is the Enoch that we are concerned with here. The lineage is Adam — Seth — Enos — Cainan — Mahalaleel — Jared — Enoch. Enoch walked with God, and after 365 years God took him — he did not die. Genesis 5:23-24 And all the days of Enoch were three hundred sixty and five years: And Enoch walked with God: and he was not; for God took him. This fact is expanded upon in Hebrews chapter 11 — among those who walked in faith. Hebrews 11:5 By faith Enoch was translated that he should not see death; and was not found, because God had translated him: for before his translation he had this testimony, that he pleased God. Enoch is also found in the genealogy of Jesus. Luke 3:37 Which was the son of Mathusala, which was the son of Enoch, which was the son of Jared, which was the son of Maleleel, which was the son of Cainan. Note; above the names are spelt differently in the New Testament which was originally written in Greek. In the time of the early church fathers, the book of Enoch was widely accepted as inspired scripture by Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Athenagoras, Tertullian, Origen and Lactantius. They all referenced Enoch in their own writings, probably because of Jude’s reference that it was a prophetic text. Jude 1:14-15 And Enoch also, the seventh from Adam, prophesied of these, saying, Behold, the Lord cometh with ten thousands of his saints, to execute judgment upon all, and to convince all that are ungodly among them of all their ungodly deeds which they have ungodly committed, and of all their hard speeches which ungodly sinners have spoken against him. -

Rewritten Bible?

CHAPTER FOUR REWRITTEN BIBLE? Introduction Philo did not only interpret small biblical units, but gave compre hensive presentations of the Laws of Moses to such an extent that one might claim that he largely rewrote the Pentateuch in the set of treatises called the Exposition qf ehe Laws qf Moses. Does he here place himself within the wider context of Jewish expository traditions? It has been attempted to group such traditions into a genre. In bis definition of the 'rewritten Bib1e' genre Ph.S. Alexander states that its framework is an account of events, and so they may be described broadly as histories. This genre is different from theological treatises, though the account of events may serve theological ends. 1 Does Philo's Exposition agree with this criterion? Philo begins with the story of Creation. He writes the who1e treatise Opif. on Gen 1-3, using the biblical form of hexaemeron, and rewrites in biblica1 sequence the stories about the Garden, the Serpent, the Fall and its consequences. He follows the biblical order in AbT. 7-16 in his account of Enos, Enoch, Noah and the Deluge, and in AbT. 17- 276 on Abraham. Several events in the life of Abraham are recorded, his migration, his adventures in Egypt, the three angelic visitors, the destruction of the cities of the Plain, the sacrifice of Isaac, the settle ment of the dispute with Lot, his victory over the four kings, Sarah and Hagar, and Sarah's death. In Jos. 1 Philo refers back to Abraham, Isaac andJacob, and in Jos. 2-156 he deals with the story ofJoseph.2 Several events in Joseph's career are included in the treatise: Joseph's dream, bis being sold to merchants, who in turn sold bim to Potiphar. -

Sermon Notes

Welcome to Rehoboth New Life Center Sunday May 5th 2019 PART 1 “HA SHEM” Proverbs 18:10 ¶The name of the LORD is a strong tower: the righteous runneth into it, and is safe. Ha Shem: The Name THE NAME OF GOD • Philippians 2:6 • Wherefore God also hath highly exalted him, and given him a name which is above every name: • 10 That at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth; Names THE NAME OF GOD • Adam God has created through the divine inspiration of the bible a • Seth method of establishing its • Enos authorship. And one of the many textual ways he does this is the • Kenan use of names and naming • Mahaleleel • Jared • Enoch NAMES THE NAME OF GOD • “RED EARTH “Adam” • “MANKIND” • Genesis 1:27 So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them. • Genesis 2:7 And the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul. NAMES THE NAME OF GOD “Seth” • “APPOINTED” • Genesis 4:25 ¶And Adam knew his wife again; and she bare a son, and called his name Seth: For God, said she, hath appointed me another seed instead of Abel, whom Cain slew. Genesis 5:4 And the days of Adam after he had begotten Seth were eight hundred years: and he begat sons and daughters: NAMES THE NAME OF GOD “Enos” • “MORTAL” or “SICK” • Genesis 5:6 ¶And Seth lived an hundred and five years, and begat Enos: • 7 And Seth lived after he begat Enos eight hundred and seven years, and begat sons and daughters: • 8 And all the days of Seth were nine hundred and twelve years: and he died. -

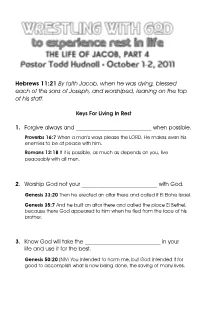

Hebrews 11:21 by Faith Jacob, When He Was Dying, Blessed Each of The

4. Trust that God is your __________________________ even when it doesn’t seem like it. Genesis 48:15 (NIV) “May the God before whom my fathers Abraham and Isaac walked, the God who has been my shepherd all my life to this day.” Hebrews 11:21 By faith Jacob, when he was dying, blessed 5. Expect God to fulfill His __________________________ without your manipulation. each of the sons of Joseph, and worshiped, leaning on the top of his staff. Genesis 48:14 (NIV) But Israel reached out his right hand and put it on Ephraim’s head, though he was the younger, and crossing his arms, he put his left hand on Manasseh’s head, even though Manasseh was Keys For Living In Rest the firstborn. 1. Forgive always and __________________________ when possible. Proverbs 16:7 When a man’s ways please the LORD, He makes even his enemies to be at peace with him. Group Discussion Questions Romans 12:18 If it is possible, as much as depends on you, live 1. Read Romans 12:18. What is the difference between living peaceably with all men. peaceably and being reconciled? Are there any relationships in your life where you need to establish peace? Are there any relationships in your life where you 2. Worship God not your __________________________ with God. need to reconcile? What do you think you need to do? Genesis 33:20 Then he erected an altar there and called it El Elohe Israel. 2. Why is it important to worship God and not your experience Genesis 35:7 And he built an altar there and called the place El Bethel, with God? Has that ever been a problem for you? Explain. -

The Book of Hebrews

The Book of Hebrews Introduction to Study: Who wrote the Epistle to the Hebrews? A. T. Robertson, in his Greek NT study, quotes Eusebius as saying, “who wrote the Epistle God only 1 knows.” Though there is an impressive list of early Bible students that attributed the epistle to the apostle Paul (i.e., Pantaenus [AD 180], Clement of Alexander [AD 187], Origen [AD 185], The Council of Antioch [AD 264], Jerome [AD 392], and Augustine of Hippo in North Africa), there is equally an impressive list of those who disagree. Tertullian [AD 190] ascribed the epistle of Hebrews to Barnabas. Those who support a Pauline epistle claim that the apostle wrote the book in the Hebrew language for the Hebrews and that Luke translated it into Greek. Still others claim that another author wrote the epistle and Paul translated it into Greek. Lastly, some claim that Paul provided the ideas for the epistle by inspiration and that one of his contemporaries (Luke, Barnabas, Apollos, Silas, Aquila, Mark, or Clement of Rome) actually composed the epistle. The fact of the matter is that we just do not have enough clear textual proof to make a precise unequivocal judgment one way or the other. The following notes will refer to the author as ‘the author of Hebrews,’ whether that be Paul or some other. Is the Book of Hebrews an Inspired Work? Bible skeptics have questioned the authenticity (canonicity) of Hebrews simply because of its unknown author. There are three proofs that should suffice the reader of the inspiration of Hebrews as it takes its rightful place in the NT. -

Hebrews 11-23-31

Hebrews 11-23-31 Prayer for illumination: please join me in prayer…. Sermon introduction: If you live long enough you will face a crisis. Many of you have faced multiple crises in the last year. Some of you have faced a health crisis. Some of you have faced a family crisis. Some of you have lost loved ones. Some of you have faced a work crisis. Some of you have faced a significant relational crisis. Some of you have faced a financial crisis. Some of you have experienced a school crisis. Unfortunately, crises come in all shapes and sizes. How do you respond when a crisis strikes? Some people panic, others plan like crazy, some work harder, others isolate themselves, manipulate others, or medicate with substances, food, or media. None of these responses brings joy and peace! How should we respond? This brings us to the book of Hebrews once again. The recipients of this letter faced a crisis. Hebrews 10:32–34 (ESV) — 32 But recall the former days when, after you were enlightened, you endured a hard struggle with sufferings, 33 sometimes being publicly exposed to reproach and affliction, and sometimes being partners with those so treated. 34 For you had compassion on those in prison, and you joyfully accepted the plundering of your property, since you knew that you yourselves had a better possession and an abiding one. The original audience experienced persecution and affliction simply for being Christians. Some even had their personal property vandalized. They were outcasts. This was a crisis. How should they respond to this crisis? How should you respond to crisis? We find the answer in Hebrews 11:23-31. -

The Watchers in Jewish and Christian Traditions

1 Mesopotamian Elements and the Watchers Traditions Ida Fröhlich Introduction By the time of the exile, early Watchers traditions were written in Aramaic, the vernacular in Mesopotamia. Besides many writings associated with Enoch, several works composed in Aramaic came to light from the Qumran library. They manifest several specific common characteristics concerning their literary genres and content. These are worthy of further examination.1 Several Qumran Aramaic works are well acquainted with historical, literary, and other traditions of the Eastern diaspora, and they contain Mesopotamian and Persian elements.2 Early Enoch writings reflect a solid awareness of certain Mesopotamian traditions.3 Revelations on the secrets of the cosmos given to Enoch during his heavenly voyage reflect the influence of Mesopotamian 1. Characteristics of Aramean literary texts were examined by B.Z. Wacholder, “The Ancient Judeo- Aramaic Literature 500–164 bce: A Classification of Pre-Qumranic Texts,” in Archaeology and History in , JSOTSup8, ed. L.H. Schiffman (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990), 257–81. the Dead Sea Scrolls 2. The most outstanding example is 4Q242, the Prayer of Nabonidus that suggests knowledge of historical legends on the last Neo-Babylonian king Nabunaid (555–539 bce). On the historical background of the legend see R. Meyer, , SSAW.PH 107, no. 3 (Berlin: Akademie, Das Gebet des Nabonid 1962). 4Q550 uses Persian names and the story reflects the influence of the pattern of the Ahiqar novel; see I. Fröhlich, “Stories from the Persian King’s Court. 4Q550 (4QprESTHARa-f),” . 38 Acta Ant. Hung (1998): 103–14. 3. H. L. Jansen, , Skrifter utgitt av Die Henochgestalt: eine vergleichende religionsgeschichtliche Untersuchung det Norske videnskaps-akademi i Oslo. -

Cain and Abel – Sermon 8Th November 2015

1 Cain and Abel – Sermon 8th November 2015 Reading: Genesis 4: 1 – 26 Cain and Abel Adam made love to his wife Eve, and she became pregnant and gave birth to Cain. She said, 2 “With the help of the LORD I have brought forth a man.” Later she gave birth to his brother Abel. Now Abel kept flocks, and Cain worked the soil. 3 In the course of time Cain brought some of 4 the fruits of the soil as an offering to the LORD. And Abel also brought an offering—fat portions from some of the firstborn of his flock. The LORD looked with favour on Abel and his offering, 5 but on Cain and his offering he did not look with favour. So Cain was very angry, and his face was downcast. 6 7 Then the LORD said to Cain, “Why are you angry? Why is your face downcast? If you do what is right, will you not be accepted? But if you do not do what is right, sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you must rule over it.” 8 Now Cain said to his brother Abel, “Let’s go out to the field.” While they were in the field, Cain attacked his brother Abel and killed him. 9 Then the LORD said to Cain, “Where is your brother Abel?” “I don’t know,” he replied. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” 10 The LORD said, “What have you done? Listen! Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground.