One-Locus-Several-Primers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artículos Publicados En Revistas Científicas Con Mención Expresa Al Proyecto Migranet En Los Agradecimientos

ARTÍCULOS PUBLICADOS EN REVISTAS CIENTÍFICAS CON MENCIÓN EXPRESA AL PROYECTO MIGRANET EN LOS AGRADECIMIENTOS PROYECTO MIGRANET- “OBSERVATORIO DE LAS POBLACIONES DE PECES MIGRADORES EN EL ESPACIO SUDOE” 1.- Araújo MJ, Ozório ROA, Antunes C (submitted). Linking ecology and nutrition: considerations on spawning migrations of diadromous fish species in Iberian Peninsula. Review. Limnetica. 2.- Araújo MJ, Ozório ROA, Bessa RJB, Kijjoa A, Gonçalves JFM, Antunes C. (submitted). Nutritional status of adult sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus Linnaeus, 1758) during spawning migration in the Minho River, NW Iberian Peninsula. Journal Applied Ichthiology. 3.- Cobo, F., Sánchez-Hernández, J., Vieira-Lanero, R., & Servia, MJ. 2012. Organic pollution induces domestication-like characteristics in feral populations of brown trout (Salmo trutta). DOI 10.1007/s10750-012-1386-4. 4.- Dias E, Morais P, Antunes C, Hoffman JC (submitted). Organic matter sources supporting the high secondary production of the bivalve Corbicula fluminea in an invaded ecosystem. Biological Invasions. 5.- Sánchez-Hernández, J., Servia, MJ., Vieira-Lanero, R., & Cobo, F. 2012. New record of translocated Phoxinus bigerri Kottelat, 2007 from a river basin in the North- West Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula. BioInvasions Records, 1 (1): 37–39. 6.- Sánchez-Hernández, J., Servia, MJ., Vieira-Lanero, R., & Cobo, F. 2012. Aplicación del análisis de los rasgos ecológicos (“traits”) de las presas para el estudio del comportamiento alimentario en peces bentófagos: el ejemplo del espinoso (Gasterosteus gymnurus Cuvier, 1829). Limnetica, 31 (1): 59-76. 7.- Sánchez-Hernández, J., Servia, MJ., Vieira-Lanero, R., Barca-Bravo, S., & Cobo, F 2012. References data on the growth and population parameters of brown trout in siliceous rivers of Galicia (NW Spain). -

Guidance Document on the Strict Protection of Animal Species of Community Interest Under the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC

Guidance document on the strict protection of animal species of Community interest under the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC Final version, February 2007 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 I. CONTEXT 6 I.1 Species conservation within a wider legal and political context 6 I.1.1 Political context 6 I.1.2 Legal context 7 I.2 Species conservation within the overall scheme of Directive 92/43/EEC 8 I.2.1 Primary aim of the Directive: the role of Article 2 8 I.2.2 Favourable conservation status 9 I.2.3 Species conservation instruments 11 I.2.3.a) The Annexes 13 I.2.3.b) The protection of animal species listed under both Annexes II and IV in Natura 2000 sites 15 I.2.4 Basic principles of species conservation 17 I.2.4.a) Good knowledge and surveillance of conservation status 17 I.2.4.b) Appropriate and effective character of measures taken 19 II. ARTICLE 12 23 II.1 General legal considerations 23 II.2 Requisite measures for a system of strict protection 26 II.2.1 Measures to establish and effectively implement a system of strict protection 26 II.2.2 Measures to ensure favourable conservation status 27 II.2.3 Measures regarding the situations described in Article 12 28 II.2.4 Provisions of Article 12(1)(a)-(d) in relation to ongoing activities 30 II.3 The specific protection provisions under Article 12 35 II.3.1 Deliberate capture or killing of specimens of Annex IV(a) species 35 II.3.2 Deliberate disturbance of Annex IV(a) species, particularly during periods of breeding, rearing, hibernation and migration 37 II.3.2.a) Disturbance 37 II.3.2.b) Periods -

Cenozoic Tectonic and Climatic Events in Southern Iberian Peninsula: Implications

Research paper Cenozoic tectonic and climatic events in southern Iberian Peninsula: implications for the evolutionary history of freshwater fish of the genus Squalius (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) Silvia Perea 1*, Marta Cobo-Simon2 and Ignacio Doadrio1 1 Biodiversity and Evolutionary Group. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, C/ José Gutiérrez Abascal, 2. 28006, Madrid, Spain 2 National Center of Biotechnology, Systems Biology Department, C/ Darwin 3. 28049, Madrid, Spain. *Corresponding author: Silvia Perea; Tel.: +34 91 4111328; fax: +34 91 5645078. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, Biodiversity and Evolutionary Group, C/ José Gutiérrez Abascal, 2. 28006, Madrid, Spain E-mail addresses: SP: [email protected] (Corresponding author) ID: [email protected] MCS: [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT Southern Iberian freshwater ecosystems located at the border between the European and African plates represent a tectonically complex region spanning several geological ages, from the uplifting of the Betic Mountains in the Serravalian-Tortonian periods to the present. This area has also been subjected to the influence of changing climate conditions since the Middle-Upper Pliocene when seasonal weather patterns were established. Consequently, the ichthyofauna of southern Iberia is an interesting model system for analyzing the influence of Cenozoic tectonic and climatic events on its evolutionary history. The cyprinids Squalius malacitanus and Squalius pyrenaicus are allopatrically distributed in southern Iberia and their evolutionary history may have been defined by Cenozoic tectonic and climatic events. We analyzed MT-CYB (510 specimens) and RAG1 (140 specimens) genes of both species to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships and to estimate divergence times and ancestral distribution ranges of the species and their populations. -

Publis14-Mistea-007 {5E1DA239

Bayesian hierarchical model used to analyze regression between fish body size and scale size: application torare fish species Zingel asper Bénédicte Fontez Nguyen The, Laurent Cavalli To cite this version: Bénédicte Fontez Nguyen The, Laurent Cavalli. Bayesian hierarchical model used to analyze regression between fish body size and scale size: application to rare fish species Zingel asper. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems, EDP sciences/ONEMA, 2014, pp.10P1-10P8. 10.1051/kmae/2014008. hal-01499072 HAL Id: hal-01499072 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01499072 Submitted on 30 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems (2014) 413, 10 http://www.kmae-journal.org c ONEMA, 2014 DOI: 10.1051/kmae/2014008 Bayesian hierarchical model used to analyze regression between fish body size and scale size: application to rare fish species Zingel asper B. Fontez(1),(2), L. Cavalli(3), Received May 24, 2013 Revised February 20, 2014 Accepted February 21, 2014 ABSTRACT Key-words: Back-calculation allows to increase available data on fish growth. The ac- hierarchical curacy of back-calculation models is of paramount importance for growth Bayes model, analysis. -

Population Genomics Data Supports Introgression Between Western Iberian

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/585687; this version posted March 22, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Population genomics data supports introgression between Western Iberian 2 Squalius freshwater fish species from different drainages 3 4 Sofia L. Mendes1, Maria M. Coelho1†, Vitor C. Sousa1†* 5 1 cE3c – Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes, Departamento de 6 Biologia Animal, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, 7 1749-016 Lisbon, Portugal 8 † equal contribution 9 *corresponding authors: [email protected] and [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/585687; this version posted March 22, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 10 Abstract 11 12 In freshwater fish, processes of population divergence and speciation are often linked 13 to the geomorphology of rivers and lakes that create barriers isolating populations. 14 However, current geographical isolation does not necessarily imply total absence of 15 gene flow during the divergence process. Here, we focused on four species of the 16 genus Squalius in Portuguese rivers: S. carolitertii, S. pyrenaicus, S. aradensis and S. 17 torgalensis. Previous studies based on eight nuclear and mitochondrial markers 18 revealed incongruent patterns, with nuclear loci suggesting that S. -

Genetic Structure of Fragmented Populations of a Threatened Endemic Percid of the Rhoˆne River: Zingel Asper

Heredity (2004) 92, 329–334 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/04 $25.00 www.nature.com/hdy Genetic structure of fragmented populations of a threatened endemic percid of the Rhoˆne river: Zingel asper J Laroche1,2 and JD Durand1,3 1Laboratoire d’Ecologie des Hydrosyste`mes Fluviaux, UMR CNRS 5023, Universite´ Claude Bernard, 43 bd du 11 Novembre 1918, 69622 Villeurbanne cedex, France; 2Laboratoire Ressources Halieutiques – Poissons Marins, Institut Universitaire Europe´en de la Mer, Place Nicolas Copernic, 29280, Plouzane´, France; 3IRD/Laboratoire Ge´nome, Populations, Interactions, UMR CNRS 5000, Universite´ Montpellier II, Station Me´diterrane´enne de l’Environnement Littoral 1, quai de la Daurade F-34200 Se`te, France Zingel asper is an endemic percid of the Rhoˆne basin equilibrium between mutation and drift. Thus, this population considered to be critically endangered. This species was shows an apparently better evolutionary potential for long- continuously distributed throughout the Rhoˆne in 1900, but term survival. Since 1930, a marked fragmentation of the today only occupies 17% of its initial area. In the present whole Rhoˆne system has appeared, related to the develop- study, five microsatellite loci were used to assess the level of ment of dams, and we assume that the significant genetic genetic variability within and among populations localized in differentiation detected between the populations could different sub-basins. Contrasting results were obtained for mainly reflect the impact of this fragmentation. -

Actualisation Des Connaissances Sur La Population D'aprons Du Rhône (Zingel Asper) Dans Le Doubs Franco-Suisse

Master Sciences de la Terre, de l'Eau et de l'Environnement Ingénierie des Hydrosystèmes et des Bassins Versants Parcours IMACOF Rapport de stage pour l'obtention de la 2ème année de Master Actualisation des connaissances sur la population d’aprons du Rhône (Zingel Asper) dans le Doubs franco-suisse - linéaire du futur Parc Naturel Régional transfrontalier - Propositions d’actions en faveur de l’espèce et de son milieu Florian BONNAIRE Septembre, 2012 Maître de stage : François BOINAY Organisme : Centre Nature Les Cerlatez Photo, 1ère de couverture : deux aprons vus le 13 août 2012 sur les gravières de Saint- Ursanne, dont le seul jeune individu observé au cours de cette campagne 2012. Photo prise par : Florian Bonnaire REMERCIEMENTS Nombreux sont ceux qui m’ont soutenu jusqu’à l’aboutissement de cette étude. Mes prochains remerciements iront donc à ces gens passionnants qui m’ont ouvert leurs portes et enrichi à leur manière cette belle aventure. Tout d’abord, mes remerciements vont à François Boinay, mon maître de stage mais aussi directeur du Centre Nature les Cerlatez. Merci pour m’avoir offert l’opportunité de faire ce stage passionnant au cœur des paysages grandioses de la vallée du Doubs franco-suisse. Merci pour ton aide précieuse mais aussi ton humour formidable que je n’oublierai pas. À Mickael Béjean, cet homme entièrement dévoué à l’apron sans qui cette étude n’aurait pas pris tout son sens. Merci pour tous ces conseils et partages d’expériences plus que bénéfiques, ainsi que pour ces quelques prospections nocturnes et subaquatiques. À Marianne Georget, animatrice du Plan National d’Action en faveur de l’apron du Rhône, pour m’avoir ouvert les portes des spécialistes, sans quoi le déroulement de ce stage n’aurait certainement pas pris cette dimension transfrontalière. -

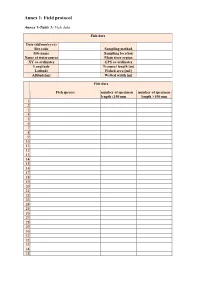

Annex 1: Field Protocol

Annex 1: Field protocol Annex 1-Table 1: Fish data Fish data Date (dd/mm/yyyy) Site code Sampling method Site name Sampling location Name of watercourse Main river region XY co-ordinates GPS co-ordinates Longitude Transect length [m] Latitude Fished area [m2] Altitude[m] Wetted width [m] Fish data Fish species number of specimen number of specimen length ≤150 mm length >150 mm 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 Annex 1-Table 2: Abiotic and method data Reference fields Site code Date dd/mm/yyyy Site name Name of watercourse or River name River region XY co-ordinates or longitude, latitude GPS co-ordinates Altitude m Sampling location Main channel/Backwaters/Mixed Sampling method Boat/Wading Fished area m2 Wetted width m Abiotic variables Altitude m Lakes upstream affecting Yes / No the site Distance from source km Flow regime Permanent / Summer dry/Winter dry/Intermittent Geomophology Naturally constrained no modification/ Braided/Sinuous/Meand regular/Meand tortuous Former floodplain No/Small/Medium/Large/Some waterbodies remaining/ Water source type Glacial/Nival/Pluvial/Groundwater Former sediment size Organic/Silt/Sand/ Gravel-Pebble-Cobble/Boulder-Rock Upstream drainage area km2 Distance from source km River slope m/km (‰) Mean air temperature Celsius (°C) Annex 1-Table 3: Human impact data (optional) Site code hChemical data Name watercourse Oxygen (mg/l or % saturation) XYZ co-ordinates or X:……………………(N) Conductivity (mS/cm) longitude latitude altitude Y:……………………(E) Z :…………………….m -

Deliverable D5.D: Report on the Position of Exotic Species in the Context of Estuaries, Rivers and Lakes Multi-Stressors and Regarding Ecosystem Services

Deliverable D5.D – Exotic species in multi-stressor context Funded by the European Union within the 7th Framework Programme, Grant Agreement 603378. Duration: February 1st, 2014 – January 31th, 2018 Deliverable D5.D: Report on the position of exotic species in the context of estuaries, rivers and lakes multi-stressors and regarding ecosystem services Lead contractor: Irstea Contributors: Maxime Logez, Benjamin Agaciak, Christine Argillier, Mario Lepage, Nils Teichert (Irstea), Rafaela Schinegger, Stefan Schmutz (BOKU), Pedro Segurado, Maria Teresa Ferreira (ULisboa), Guillem Chust, Ainhize Uriarte, Angel Borja (AZTI) Due date of deliverable: Month 33 Actual submission date: Month 37 Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Page 1/51 Deliverable D5.D – Exotic species in multi-stressor context Content Non-technical summary ............................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 Methods ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Available data ........................................................................................................................ -

Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats Convention Relative À La Conservation De La Vie Sauvage Et Du Milieu Naturel De L'europe

European Treaty Series - No. 104 Série des traités européens – n° 104 Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats Convention relative à la conservation de la vie sauvage et du milieu naturel de l'Europe Bern/Berne, 19.IX.1979 Appendix II – STRICTLY PROTECTED FAUNA SPECIES Annexe II – ESPÈCES DE FAUNE STRICTEMENT PROTÉGÉES (*) (Med.) = in the Mediterranean/en Méditerranée VERTEBRATES/VERTÉBRÉS Mammals/Mammifères Birds/Oiseaux Reptiles Amphibians/Amphibiens Fish/Poissons INVERTEBRATES/INVERTÉBRÉS Arthropods/Arthropodes Molluscs/Mollusques Echinoderms/Échinodermes Cnidarians/Cnidaires Sponges/Éponges Notes to Appendix II / Notes à l'annexe II _____ (*) Status in force since 1 March 2002. Appendices are regularly revised by the Standing Committee. Etat en vigueur depuis le 1er mars 2002. Les annexes sont régulièrement révisées par le Comité permanent. ETS/STE 104 – Bern Convention / Convention de Berne (Appendix/Annexe II), 19.IX.1979 __________________________________________________________________________________ VERTEBRATES/VERTÉBRÉS Mammals/Mammifères INSECTIVORA Erinaceidae * Atelerix algirus (Erinaceus algirus) Soricidae * Crocidura suaveolens ariadne (Crodidura ariadne) * Crocidura russula cypria (Crocidura cypria) Crocidura canariensis Talpidae Desmana moschata Galemys pyrenaicus (Desmana pyrenaica) MICROCHIROPTERA all species except Pipistrellus pipistrellus toutes les espèces à l'exception de Pipistrellus pipistrellus RODENTIA Sciuridae Pteromys volans (Sciuropterus russicus) Sciurus anomalus -

Life-Cycle Responses of a Mediterranean Non-Migratory

Received: 28 July 2017 Revised: 15 April 2018 Accepted: 29 May 2018 DOI: 10.1002/eco.1998 RESEARCH ARTICLE Life‐cycle responses of a Mediterranean non‐migratory cyprinid species, the Northern Iberian chub (Squalius carolitertii Doadrio, 1988), to streamflow regulation Carlos M. Alexandre1 | Maria T. Ferreira2 | Pedro R. Almeida1,3 1 Universidade de Évora, MARE–Centro de Ciências do Mar e do Ambiente, Évora, Abstract Portugal Streamflow is considered a driver of interspecific and intraspecific life‐history differ- 2 Universidade de Lisboa, Centro de Estudos ences among freshwater fish. Therefore, dams and related flow regulation can have Florestais, Instituto de Agronomia, Lisboa, Portugal deleterious impacts on their life cycles. The main objective of this study was to assess 3 Universidade de Évora, Departamento de existing differences in the growth and reproduction patterns of a non‐migratory fish Biologia, Escola de Ciências e Tecnologia, species (the Northern Iberian chub, Squalius carolitertii, Doadrio, 1988), between non- Évora, Portugal Correspondence regulated and regulated watercourses. For 1 year, samples were collected from two Carlos M. Alexandre, MARE–Centro de populations of Iberian chub, inhabiting rivers with nonregulated and regulated flow Ciências do Mar e do Ambiente, Universidade de Évora, Largo dos Colegiais 2, 7004‐516, regimes. Flow regulation for water storage promoted changes in chub's condition, Évora, Portugal. duration of spawning, fecundity, and oocyte size. However, this non‐migratory spe- Email: [email protected] cies was less responsive to streamflow regulation than other native potamodromous Funding information Portuguese Science Foundation, Grant/Award species. Findings from this study are important to understand changes imposed by Numbers: SFRH/BPD/108582/2015 and regulated rivers and can be used to support the implementation of suitable river man- UID/MAR/04292/2013 agement practices. -

Zingel Streber): Implications for Conservation

Erschienen in: Aquatic Conservation : Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems ; 28 (2018), 3. - S. 587-599 https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2878 River damming drives population fragmentation and habitat loss of the threatened Danube streber (Zingel streber): Implications for conservation Alexander Brinker1,2 | Christoph Chucholl3 | Jasminca Behrmann‐Godel2 | Michaela Matzinger4 | Timo Basen1 | Jan Baer1 1 Fisheries Research Station of Baden‐Württemberg, Langenargen, Germany Abstract ‐ 2 University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany 1. The Danube streber, Zingel streber, is a threatened and data deficient percid fish endemic to 3 EcoSurv, Schnaitsee, Germany the Danube catchment. The study provides the first data on distribution, life history, and ‐ 4 Office of the State Government of Upper genetic structure of the species at the upstream limit of its historic distribution (south western Austria, Linz, Austria Germany). Correspondence 2. A 3‐year survey effort with 143 fishing events identified several small, fragmentary popula- Alexander Brinker, Fisheries Research Station tions covering only 7% of the historical range of the species. Census population sizes (N )of of Baden‐Württemberg, Argenweg 50/1, c 88085 Langenargen, Germany. these subpopulations were estimated from mark–recapture data at <200 individuals. Effective Email: [email protected] population sizes (Ne), calculated from genetic data (microsatellite genotyping), were much Funding information smaller still, at <15 individuals, resulting in an Nc/Ne ratio of <0.25, strongly indicating that Fischereiabgabe Baden‐Württemberg populations are seriously affected by genetic drift and inbreeding, and are thus facing a severe extinction risk. 3. Life‐history parameters recorded during the study indicate a rapid life cycle, with both sexes probably attaining sexual maturity at the age of 1 year or older.