Reuse and Recycling Systems for Selected Beverage Packaging From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Packing and Crating Basics C2C Care Webinar to Begin With

Packing and Crating Basics C2C Care Webinar To begin with... ● Determine the needs of your object ○ What is your object made out of? ○ How will your crate be used? ■ Storage? ■ Traveling? ● How many times will the crate travel? ○ Single venue vs. multi-venue Storage vs. Traveling Crates ● There is a difference between crates for storage and crates for transit ● Different materials will be used for storage vs. transit ● Types of foam: ○ Thermal insulating foams for transit ■ U-foam ■ Esterfoam ■ Polystyrene Extruded foam ○ Shock absorbing foams for transit and storage ■ Ethafoam (various densities) ■ Volara Storage Concerns ● Off-gassing inside the storage crate ○ Avoid using Esterfoam, U-foam, and Polystyrene foams. ■ Objects should not be stored in closed crates with these foams for more than 90 days. ○ Be aware of the materials the object will be contact with. ○ Be aware of the composition of the object itself. ● Object should be easy to access and identify Transit Concerns ● Vibration and shock ○ Use an appropriate amount and type of foam ● Changes in temperature and climate ○ Line crates with thermal insulating foam such as U-foam, Esterfoam, or Polystyrene Extruded foam ● Handling ○ Crate should have clear stencils, skids, and handles to encourage safe handling ● Ease of packing/unpacking ○ Clear packing/unpacking instructions/diagrams Flatworks Common packing solutions for flatworks: ● Trays ○ Usually for framed works ○ allows multiple objects to be packed in the same crate ● Travel frames ○ For unframed canvases, or objects that -

Structures and Exterior Envelope

Integration: Structure and Envelope Integrated Building Systems Part I: Integration Principles Part II: Structure and the Exterior Envelope Part III: Integration Case Studies 4.405Building Systems Building Systems: Definitions 1. Foundation/Subgrade (SITE) 2. Superstructure (STRUCTURE) Daly, Genik: Valley Center, CA, 2000. 3. Exterior Envelope (SKIN) 4. Interior Partitions (SPACE PLAN) 5. Mechanical Systems (SERVICES) 6. Furnishings (STUFF) Stuff Space Plan Services Structure Sources: Brand, Howard, Skin How Buildings Learn. Site Also see Turner, Gregory, Construction Economics and Building Design Bensonwood Timber Frame: 1996. Image by MIT OCW. 4.405Building Systems Building Systems: Definitions 1. Foundation/Subgrade (SITE) 2. Superstructure (STRUCTURE) 3. Exterior Envelope (SKIN) 4. Interior Partitions (SPACE PLAN) 5. Mechanical Systems (SERVICES) 6. Furnishings (STUFF) Rush specifies only four systems; • Structure • Envelope • Interior • Mechanical Source: Rush, Richard, The Building Systems Integration Handbook Curtainwall and raised floor construction. Image by MIT OCW. Integration Levels Definitions 1. Remote: systems are Remote physically separated from one another but yet still coordinated functionally Touching 2. Touching: One system rests on another Connected 3. Connected: one system is mechanically fastened and dependent on another Meshed 4. Meshed: systems occupy the same space Unified 5. Unified: systems share the same physical elements Five Levels of Integration Image by MIT OCW. Image by MIT OCW. Performance Mandates Roof Assembly: Performance is, generally, the Roof structure and measurement of achievement structural deck (S) Roofing (E) E against intention. Ceiling (I) Lighting (MI) Roof Assembly S Wall Assembly: 1. Spatial Performance Wall structure (the support plus any lateral bracing, shear panels, I MI 2. Thermal Performance or sheathing) (S) I Exterior wall covering (EI) 3. -

Paper 101 with Courtney Cerruti

Paper 101 with Courtney Cerruti Chapter 1 - Paper 101 Paper 101 (pop drum music) - Paper is one of those medium's that really is so versatile, and can be used for so many projects. I love to make a-million-and-one different things out of paper. Anywhere from book crafts, to paper crafts, things like making cards, doing collages, or even something like making paper flowers. And for all of those projects, I would use a different weight of paper. And it's really helpful to understand a little bit more about paper when you start to work with it. How to find grain and what projects should be used with which types of paper. If you're familiar with the concept that fabric has a grain, paper also has a grain. And that just indicates which way the fibers of the paper, when it's made, are running. If they're predominantly running vertically or horizontally. So, we do this things called the "bounce test," which always you to just fold the paper in one direction, and just gently bounce it to see how much resistance you have, and then you would turn it the opposite direction, and do the same thing. And you can see, that I really press this down. So, that means, that my grain is going parallel to where I'm creating this little fold. So, my grain runs this way. If we go back to that other direction, we can see how hard that is to press it down. And that's against the grain. -

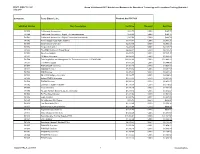

Festo Didactic, Inc. SKU/Part Number Item Description List Price Discount

FESTO DIDACTIC, INC. Group 38224-Award 23077 Materials and Equipment for Educational Technology and Occupational Training (Statewide) July 2019 Contractor: Festo Didactic, Inc. Contract No: PC67815 SKU/Part Number Item Description List Price Discount Net Price 581539 Cables and Accessories $258.71 5.00% $245.77 581540 Cables and Accessories - Digital Telecommunications $574.89 5.00% $546.15 581541 Cables and Accessories - Digital Communications Add-On $467.09 5.00% $443.74 581542 Power Supply / Dual Audio Amplifier $3,018.17 5.00% $2,867.26 581549 Dual Function Generator $2,903.19 5.00% $2,758.03 581552 Frequency Counter $2,249.25 5.00% $2,136.79 581555 True RMS Voltmeter / Power Meter $2,292.37 5.00% $2,177.75 581558 Spectrum Analyzer $8,407.76 5.00% $7,987.37 581561 RF/Noise Generator $4,024.23 5.00% $3,823.02 581564 Data Acquisition and Management for Telecommunications (LVDAM-COM) $23,642.33 5.00% $22,460.21 581571 TTS Power Supply $1,415.66 5.00% $1,344.88 581574 AM/DSB/SSB Generator $4,804.25 5.00% $4,564.04 581577 AM/DSB Receiver $3,370.14 5.00% $3,201.63 581580 SSB Receiver $3,370.14 5.00% $3,201.63 581583 Direct FM Multiplex Generator $5,162.77 5.00% $4,904.63 581586 Indirect FM/PM Generator $4,517.43 5.00% $4,291.56 581589 FM/PM Receiver $6,740.28 5.00% $6,403.27 581592 Enclosure / Supply Regulator $1,178.53 5.00% $1,119.60 581593 Clock Generator $2,486.40 5.00% $2,362.08 581596 Pseudo-Random Binary Sequence Generator $3,233.76 5.00% $3,072.07 581599 Bit Error Rate Indicator $1,624.06 5.00% $1,542.86 581602 Logic Analyzer $1,997.74 -

KMR Catalogue 2021

The partner of craftsmen Catalogue 2021 New! www.kmr-group.eu Company history Welcome to KMR! 1914 Karl Mathias Reich founded the business with 5 employees and started manufacturing wire and equipment that uses wire. 1925 The first stationary carpentry equipment. 1960s New creations like the first portable pneumatic nailers. 2000 Foundation of the Karl M. Reich GmbH production and distribution company. 2013 The Karl M. Reich Verbindungstechnik brand was taken over by the German BeA group. 2016 The products bear the initials of the founder Karl Mathias Reich: KMR. 2018 Introduction of gas nailers into the product range 2020 Relaunch of the KMR homepage, state-of-the-art technique: modern, quick, user-friendly and all information on tools and fasteners at your disposal any time and anywhere! 2021 Introduction of the new KMR 3-in-1 Multi tool AC/90-942C. The unique nailing tool for 3 different nail collation types. KMR – The partner of craftsmen All information concerning our tools and fasteners can be retrieved as of now on mobile devices at any time. Our product information is at your disposal exactly when you need it - in the office, on the construction site, in the factory or when visiting a client. www.kmr-group.eu gives you quick and easy all information on our product range: Our tools for professionals and fasteners in different materials and dimensions. Furthermore you will find all technical details on our tools, helpful application hints for your projects as well as a huge download area. The download area contains all important documents and declarations of performance (DoPs), CE-label, ETA approvals, as well as manuals - all these documents are available online at any time. -

Vacuum Pump Page 6 IMPORTANT: Read All Instructions Before Using

Festool GmbH Wertstraße 20 D-73240 Wendlingen www.festoolusa.com Instruction manual - Vacuum pump Page 6 IMPORTANT: Read all instructions before using. Guide d’utilisation - Pompe à vide Page 14 IMPORTANT: Lire toutes les instructions avant de démarrer les travaux. Manual de instrucciones - Bomba de vacío Página 23 IMPORTANTE: Lea todas las instrucciones antes de usar. Instruction manual Guide d’utilisation Manual de instrucciones VAC PMP 708410_001 1-1 1-2 1 1-4 1-3 2-5 2-4 2-3 2-2 2-6 2-1 2 Contents Functional description.......................... 8 Symbols................................................ 6 Preparing for use ................................. 9 About this manual................................ 6 Service and maintenance ..................... 11 Safety instructions ............................... 7 Environment ......................................... 11 Intended use ........................................ 8 Troubleshooting.................................... 12 Technical data ...................................... 8 Symbols Symbol Significance Symbol Significance Vvolts Warning of general danger A amperes Risk of electric shock W Watt Hz hertz Read operating instructions and safety rpm rounds per minute notices! ~ a.c. alternating current Do not dispose of as domestic waste. d.c. direct current ft feet Warning: Hot surface! in inch lb pound Tip or advice mbar airpressure in millibar Handling instruction °F temperature in degrees Fahrenheit About this manual Save these instructions It is important for you to read and understand this manual. The information it contains relates to protecting your safety and preventing problems. The symbols below are used to help you recognize this information. DANGER Description of imminent haz- NOTICE Statement including nature of ard and failure to avoid hazard hazard and possible result. will result in death. HINT Indicates information, notes, WARNING Description of hazard and or tips for improving your suc- possible resulting injures or cess using the tool. -

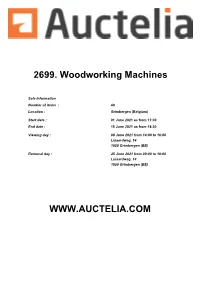

2699. Woodworking Machines

2699. Woodworking Machines Sale Information Number of items : 40 Location : Grimbergen (Belgium) Start date : 01 June 2021 as from 17:00 End date : 15 June 2021 as from 18:30 Viewing day : 08 June 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 Luiaardweg, 14 1850 Grimbergen (BE) Removal day : 25 June 2021 from 09:00 to 16:00 Luiaardweg, 14 1850 Grimbergen (BE) WWW.AUCTELIA.COM The General Terms and Conditions and the Specific conditions of sale apply to this online Auction SPECIFIC CONDITIONS - 2699. Woodworking Machines START DATE 01 June 2021 as from 17:00 END DATE 15 June 2021 as from 18:30 VIEWING 08 June 2021 from 14:00 to 16:00 Luiaardweg, 14 1850 Grimbergen (BE) REMOVAL 25 June 2021 from 09:00 to 16:00 Luiaardweg, 14 1850 Grimbergen (BE) In order to be able to pick up the Lots, the total amount due has to be paid. The Lots can only be removed if the Buyer shows on the removal day the proforma invoice and signs the delivery note. WARNING: The Buyer is fully responsible for the dismantling, loading and transportation of the bought Lots. WARNING: If Buyers do not collect their goods at the removal date, time and address mentioned above, extra storage and transport costs will be charged. AUCTION FEES Auction Fees (based on Final Selling Price per Piece) - Amounts less than €15,000 17% of the final selling price - Amounts more than €15,000 12% of the final selling price VAT 0.00 % on the highest bid and/or accepted by the Seller and on the Auction fees PAYMENT Within 3 business days of reception by e-mail of the proforma invoice, the Buyer must transfer the total amount due to the bank account below and mention the invoice number: Auctelia ING 363-4520918-79 / IBAN : BE58 3634 5209 1879 / BIC BBRUBEBB BNPPF 035-7704702-33 / IBAN : BE79 0357 7047 0233 / BIC : GEBABEBB ORGANIZER AUCTELIA Rue Emile Francqui 6/3 B-1435 Mont-Saint-Guibert, Belgique, 6 1435 Mont-Saint-Guibert (BE) SUPERVISION EXTENSION OF If there is at least one Bid within the last 5 minutes of a sale, the closing time is extended by 5 minutes until there is no more ONLINE AUCTION Bid. -

Reusable Vs Single-Use Packaging

REUSABLE VS A review of SINGLE-USE environmental PACKAGING impacts EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 A REVIEW OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS As the global population has grown and Currently, most waste management society has become more fast-paced, there systems prioritise recycling as the has been an increased demand for, and main method of reducing the amount therefore production of, more convenient, of waste going to disposal, which, in easy-to-use, on-the-go products. This terms of circular economy strategies, demand, coupled with globalisation and should be considered as one of the last trade liberalisation, has translated into management options, after it has been consumption patterns that are taking a toll determined that the product (or parts of on Earth’s capacity to replenish itself. In it) can no longer be reused, repurposed, Europe, packaging alone represents 36% remanufactured or reinserted into the of municipal solid waste1. While individual production line. On top of that, materials countries attempt to solve their waste are not being recycled at a high enough management issues and resources continue rate to ensure that our waste is managed to be depleted at a rate faster than they can sustainably. Reuse avoids the need for be regenerated, the global economy loses resource extraction and reduces energy about $80-120 billion in packaging that use compared to the manufacturing of could be reused or recycled2. new products and recycling. In addition, it can incentivise a shift toward more conscious consumption and reshape our relationship to products. This report aims at understanding the benefits of reuse by evaluating the multi-layered environmental impacts of both single-use and reusable types of packaging through an in-depth comparative analysis of 32 Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies. -

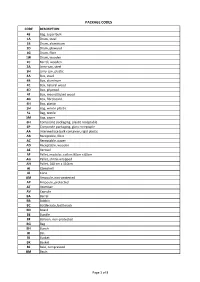

Package Codes

PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION 43 Bag, super bulk 1A Drum, steel 1B Drum, aluminium 1D Drum, plywood 1G Drum, fibre 1W Drum, wooden 2C Barrel, wooden 3A Jerry-can, steel 3H Jerry-can, plastic 4A Box, steel 4B Box, aluminum 4C Box, natural wood 4D Box, plywood 4F Box, reconstituted wood 4G Box, fibreboard 4H Box, plastic 5H Bag, woven plastic 5L Bag, textile 5M Bag, paper 6H ComposIte packaging, plastic receptable 6P Composite packaging, glass receptaple AA Intermediate bulk container, rigid plastic AB Receptable, fibre AC Receptable, paper AD Receptable, wooden AE Aerosol AF Pallet, modular, collars 80cm x 60cm AG Pallet, shrink-wrapped AH Pallet, 100 cm x 110cm AI Clamshell AJ Cone AM Ampoule, non-protected AP Ampoule, protected AT Atomiser AV Capsule BA Barrel BB Bobbin BC Bottlecrate, bottlerack BD Board BE Bundle BF Balloon, non-protected BG Bag BH Bunch BI Bin BJ Bucket BK Basket BL Bale, compressed BM Basin Page 1 of 8 PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION BN Bale, non-compressed BO Bottle, non-protected, cylindrical BP Balloon, protected BQ Bottle, protected cylindrical BR Bar BS Bottle, non-protected, bulbous BT Bolt BU Butt BV Bottle, protected bulbous BW Box, for liquids BX Box BY Board, in bundle/bunch/truss, BZ Bars, in bundle/bunch/truss CA Can, rectangular CB Beer crate CC Churn CD Can, with handle and spout CE Creel CF Coffer CG Cage CH Chest CI Canister CJ Coffin CK Cask CL Coil CM Collis CN Container not otherwise specified as transport equipment CO Carboy, non-protected CP Carboy, protected CQ Cartdidge CR Crate CS Case CT -

Is Your Water Bottle Continually Dripping Or Emptying

Thank you for purchasing a 64 oz dog or rabbit bottle Follow these tips and instructions for a better water bottle experience Bottles include a plastic cap with stainless steel tube and ball bearings, bottle is BPA free. Please note, a 64 oz bottle works best when used on an outside cage, because of the capacity of the bottle it will drip easier than a smaller bottle. For bottles to be used on a crate or xpen inside of the home we recommend a smaller size bottle, or a bottle that works on a valve not a vacuum. It is very important that you use both wires that come with the bottle, because of the weight of the water bottle when full you do not want to rest the tube on a cage wire, it should be held up by the support wire. Follow these steps, 1. Check inside the cap of your bottle, inside the cap will be a rubber gasket. Wide Mouth 64 oz bottles have a yellow gasket If the gasket is missing or damaged your bottle will drip, drip, drip, call for a gasket if yours is missing. 2. It is recommend you position both wires using an empty bottle, once you have the wires where you want them pinch the hooks closed so each time you take bottle on and off you do not have to re-position the wires. 3. Fill water bottle completely full with room temperature water, a bottle filled part way or with cold water will take longer to create a vacuum and will drip more. -

Fine Art Logistics Packing Catalogue Table of Content

Fine Art Logistics Packing catalogue Table of content The hasenkamp group 5 The hasenkamp Padding System 28 Edge protection ................................................................................................................. 28 The art of packing 6 Foams ................................................................................................................................. 30 haska FP17.01 ......................................................................................................................................30 The hasenkamp packages 8 haska EF220 / haska EF400 ............................................................................................................31 haska FB20 / haska FB40 .................................................................................................................32 Softpacking / cardboard softpacking .................................................................................8 haska FS150 .........................................................................................................................................33 Softpacking.............................................................................................................................................. 8 Vacuum cushions .............................................................................................................. 34 Cardboard softpacking ......................................................................................................................... 9 The -

Primitive Central PA Grandpa's Portable Wood Tool Carry Box W Pair Vintage 18C Antique Style Solid Brass Victorian Saw Hole Storage Andirons Chippendale Urns

Primitive Central PA Grandpa's Portable Wood Tool Carry Box w Pair Vintage 18c Antique Style Solid Brass Victorian Saw Hole Storage Andirons Chippendale Urns Antique Pre-1950 Central PA Stained Glass RIBBONS Window Vintage VG Blue White Delft Pottery Ceramic Inkwell Ink Well Panel 44 WIDE x 24 TALL Raised Tray Set 28" Antique 1900s Amber Glass Bottle Embossed Icons Set Bookends Mid Century Modern Glass Block Ice Cube Etched Advertising Store Dispenser Columbia University Lot 173 NOS Vintage Harvard Standard Metal Typer Medals Vintage 1960s Nude Nymphs Bathing Relief Carved Coffee Tray Good Luck Clover Tokens Table Smaller 29" W Vtg 1987 Oak Ridge Studio MCM Stain Glass Leaded Shade Vintage 1960s Grungie Medium Size Painters Carpenters 30"T Hanging Lamp - FOR REPAIR Ladder Planter Stand Antique Office c1929 "Johnson Chair Co Chicago" Oak Banker Vintage Crouse Hinds Explosion Proof Light w Cage Glass Jury Desk Arm Chair 4 Cover Marked Antique Office 1920s SIKES Quartersawn Oak Jury Banker Vintage 1950s Small Wood & Metal Supports Ladder Grungie Windsor Desk Arm Chair Paint Drips Strong Bruning Drafting Machine 2699 Clamp Desk Arm w Ruler RARE 1895d Victorian Photo Album Centennial Revival Liberty Bell & Writing Desk Antique Grandpa's Shop Class Farm Country Barn Milking Stool Bucket Bench 24" W Vtg Mid Century Drink Coke Yellow Red 1966 Coca Cola Bottle Carrier Crate Box Antique Great Grandpa Made Primitive Wood Garden Carrier Tool Organizer Old Nail Dated 1965 All Metal Milk Crate Martin Century Farms Pennsylvania Green Square Vintage c1949 Grandpa's Handmade Antique Big Old Wood Tool Box Holder Carrier Pair Bookends Mid Century Modern Glass Block Ice Cube Etched Columbia University Antique Office 1920s Marble Shattuck OH Quartersawn Oak Banker Desk Arm Chair Vintage Portable Coal Stove Perfection No.