Evolutions of Choral Music, Frank Martin Mass for Double Choir, and Ted Hearne Sound from the Bench

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

THIRD COAST PERCUSSION with Notre Dame Vocale, Carmen-Helena Téllez, Director PRESENTING SERIES TEDDY EBERSOL PERFORMANCE SERIES SUN, JAN 26 at 2 P.M

THIRD COAST PERCUSSION with Notre Dame Vocale, Carmen-Helena Téllez, director PRESENTING SERIES TEDDY EBERSOL PERFORMANCE SERIES SUN, JAN 26 AT 2 P.M. LEIGHTON CONCERT HALL DeBartolo Performing Arts Center University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana AUSTERITY MEASURES Concert Program Mark Applebaum (b. 1967) Wristwatch: Geology (2005) (5’) Marc Mellits (b. 1966) Gravity (2012) (11’) Thierry De Mey (b. 1956) Musique de Tables (1987) (8’) Steve Reich (b. 1936) Proverb (1995) (14’) INTERMISSION Timo Andres (b. 1985) Austerity Measures (2014) (25’) Austerity Measures was commissioned by the University of Notre Dame’s DeBartolo Performing Arts Center and Sidney K. Robinson. This commission made possible by the Teddy Ebersol Endowment for Excellence in the Performing Arts. This engagement is supported by the Arts Midwest Touring Fund, a program of Arts Midwest, which is generously supported by the National Endowment for the Arts with additional contributions from the Indiana Arts Commission. PERFORMINGARTS.ND.EDU Find us on PROGRAM NOTES: Mark Applebaum is a composer, performer, improviser, electro-acoustic instrument builder, jazz pianist, and Associate Professor of Composition and Theory at Stanford University. In his TED Talk, “Mark Applebaum, the Mad Scientist of Music,” he describes how his boredom with every familiar aspect of music has driven him to evolve as an artist, re-imagining the act of performing one element at a time, and disregarding the question, “is it music?” in favor of “is it interesting?” Wristwatch: Geology is scored for any number of people striking rocks together. The “musical score” that tells the performs what to play is a watch face with triangles, squares, circles and squiggles. -

Art Works Grants

National Endowment for the Arts — December 2014 Grant Announcement Art Works grants Discipline/Field Listings Project details are as of November 24, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Art Works grants supports the creation of art that meets the highest standards of excellence, public engagement with diverse and excellent art, lifelong learning in the arts, and the strengthening of communities through the arts. Click the discipline/field below to jump to that area of the document. Artist Communities Arts Education Dance Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 168 Artist Communities Number of Grants: 35 Total Dollar Amount: $645,000 18th Street Arts Complex (aka 18th Street Arts Center) $10,000 Santa Monica, CA To support artist residencies and related activities. Artists residing at the main gallery will be given 24-hour access to the space and a stipend. Structured as both a residency and an exhibition, the works created will be on view to the public alongside narratives about the artists' creative process. Alliance of Artists Communities $40,000 Providence, RI To support research, convenings, and trainings about the field of artist communities. Priority research areas will include social change residencies, international exchanges, and the intersections of art and science. Cohort groups (teams addressing similar concerns co-chaired by at least two residency directors) will focus on best practices and develop content for trainings and workshops. -

Norfolk Chamber Music Festival Also Has an Generous and Committed Support of This Summer’S Season

Welcome To The Festival Welcome to another concerts that explore different aspects of this theme, I hope that season of “Music you come away intrigued, curious, and excited to learn and hear Among Friends” more. Professor Paul Berry returns to give his popular pre-concert at the Norfolk lectures, where he will add depth and context to the theme Chamber Music of the summer and also to the specific works on each Friday Festival. Norfolk is a evening concert. special place, where the beauty of the This summer we welcome violinist Martin Beaver, pianist Gilbert natural surroundings Kalish, and singer Janna Baty back to Norfolk. You will enjoy combines with the our resident ensemble the Brentano Quartet in the first two sounds of music to weeks of July, while the Miró Quartet returns for the last two create something truly weeks in July. Familiar returning artists include Ani Kavafian, magical. I’m pleased Melissa Reardon, Raman Ramakrishnan, David Shifrin, William that you are here Purvis, Allan Dean, Frank Morelli, and many others. Making to share in this their Norfolk debuts are pianist Wendy Chen and oboist special experience. James Austin Smith. In addition to I and the Faculty, Staff, and Fellows are most grateful to Dean the concerts that Blocker, the Yale School of Music, the Ellen Battell Stoeckel we put on every Trust, the donors, patrons, volunteers, and friends for their summer, the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival also has an generous and committed support of this summer’s season. educational component, in which we train the most promising Without the help of so many dedicated contributors, this festival instrumentalists from around the world in the art of chamber would not be possible. -

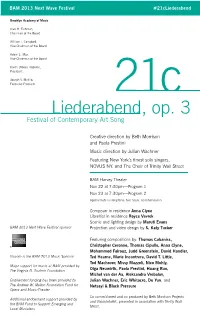

21C Liederabend , Op 3

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #21cLiederabend Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer 21c Liederabend, op. 3 Festival of Contemporary Art Song Creative direction by Beth Morrison and Paola Prestini Music direction by Julian Wachner Featuring New York’s finest solo singers, NOVUS NY, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street BAM Harvey Theater Nov 22 at 7:30pm—Program 1 Nov 23 at 7:30pm—Program 2 Approximate running time: two hours, no intermission Composer in residence Anna Clyne Librettist in residence Royce Vavrek Scenic and lighting design by Maruti Evans BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Projection and video design by S. Katy Tucker Featuring compositions by: Thomas Cabaniss, Christopher Ceronne, Thomas Cipullo, Anna Clyne, Mohammed Fairouz, Judd Greenstein, David Handler, Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Ted Hearne, Marie Incontrera, David T. Little, Tod Machover, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Major support for music at BAM provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Olga Neuwirth, Paola Prestini, Huang Ruo, Michel van der Aa, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Endowment funding has been provided by Julian Wachner, Eric Whitacre, Du Yun, and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Netsayi & Black Pressure Opera and Music-Theater Co-commisioned and co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects Additional endowment support provided by and VisionIntoArt, presented in association with Trinity Wall the BAM Fund to Support Emerging and Street. Local Musicians 21c Liederabend Op. 3 Being educated in a classical conservatory, the Liederabend (literally “Song Night” and pronounced “leader-ah-bent”) was a major part of our vocal educations. -

“Pave the Path for Your Illinois Journey”

2020 sonorities The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music “Pave the path for your Illinois journey” A Look Inside the Completed Smith Hall Renovations Dear Friends of the School of Music, Published for the alumni and friends of the School of Music at the University of Illinois at he 2019/20 academic year is my first as director of the school Urbana-Champaign. and as a member of the faculty, and in my short tenure, I’ve The School of Music is a unit of the College of been repeatedly astonished by the depth and breadth of the Fine + Applied Arts and has been an accredited world-class music programs that have been built here. From institutional member of the National Association T of Schools of Music since 1933. our Lyric Theatre program to our symphony orchestra, from the Kevin Hamilton, Dean of the College of Fine + Black Chorus to the Experimental Music Studios, from the award-winning research Applied Arts being conducted in musicology and music education to the spirited performances Jeffrey Sposato, Director of the School of Music of the Marching Illini, the students and faculty at Illinois are second to none. It’s a true honor and privilege to join them! Michael Siletti, Editor Illinois graduates play leading roles in hundreds of orchestras, choruses, bands, Jessica Buford, Copy Editor K–12 schools, and colleges and universities. The School of Music is first and foremost Design and layout by Studio 2D a resource for the state of Illinois, but our students and faculty come from around Cover photograph by Michael Siletti the world, and the impact of our alumni and faculty is global as well. -

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-Ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017 Compact Discs 2L Records Under The Wing of The Rock. 4 sound discs $24.98 2L Records ©2016 2L 119 SACD 7041888520924 Music by Sally Beamish, Benjamin Britten, Henning Kraggerud, Arne Nordheim, and Olav Anton Thommessen. With Soon-Mi Chung, Henning Kraggerud, and Oslo Camerata. Hybrid SACD. http://www.tfront.com/p-399168-under-the-wing-of-the-rock.aspx 4tay Records Hoover, Katherine, Requiem For The Innocent. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4048 681585404829 Katherine Hoover: The Last Invocation -- Echo -- Prayer In Time of War -- Peace Is The Way -- Paul Davies: Ave Maria -- David Lipten: A Widow’s Song -- How To -- Katherine Hoover: Requiem For The Innocent. Performed by the New York Virtuoso Singers. http://www.tfront.com/p-415481-requiem-for-the-innocent.aspx Rozow, Shie, Musical Fantasy. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4047 2 681585404720 Contents: Fantasia Appassionata -- Expedition -- Fantasy in Flight -- Destination Unknown -- Journey -- Uncharted Territory -- Esme’s Moon -- Old Friends -- Ananke. With Robert Thies, piano; The Lyris Quartet; Luke Maurer, viola; Brian O’Connor, French horn. http://www.tfront.com/p-410070-musical-fantasy.aspx Zaimont, Judith Lang, Pure, Cool (Water) : Symphony No. 4; Piano Trio No. 1 (Russian Summer). 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4003 2 888295336697 With the Janacek Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Winograd, violin; Peter Wyrick, cello; Joanne Polk, piano. http://www.tfront.com/p-398594-pure-cool-water-symphony-no-4-piano-trio-no-1-russian-summer.aspx Aca Records Trios For Viola d'Amore and Flute. -

SOUND from the BENCH Music by Ted Hearne Conducted by Donald Nally

SOUND FROM THE BENCH Music by Ted Hearne conducted by Donald Nally Performed by The Crossing Katy Avery Michael Jones Jessica Beebe Heather Kayan Karen Blanchard Mark Laseter Steven Bradshaw Chelsea Lyons Colin Dill Maren Montalbano Micah Dingler Rebecca Myers Robert Eisentrout Becky Oehlers Allie Faulkner Daniel Schwartz Ryan Fleming Rebecca Siler Joanna Gates Daniel Spratlan Dimitri German Elisa Sutherland Steven Hyder Jason Weisinger with instrumentalists Taylor Levine, electric guitar James Moore, electric guitar Ron Wiltrout, drums/percussion lighting design by Ian King sound design by Garth MacAleavey text for Sound from the Bench by Jena Osman produced by Beth Morrison Morrison Projects creative producer Beth Morrison general manager Jecca Barry production manager James Fry associate producer Mariel O’Connell company manager Liene Camarena Fogele Produced in association with The Crossing Special Thanks to Frederick Morrsion and Catherine Lord Sound from the Bench, an album recorded by Ted Hearne, Donald Nally and The Crossing and produced by Nick Tipp, will be released next month on Cantaloupe Music. See cantaloupemusic.com for more details. PROGRAM Consent (2014) Ripple (2012) Privilege (2010) 1. motive/mission 2. casino 3. burning tv song 4. they get it 5. we cannot leave [Break] Sound from the Bench (2014, rev. 2016) 1. How to throw your voice 2. Mouth piece 3. (Ch)oral argument 4. Simple surgery 5. When you hear ABOUT THE ARTISTS: TED HEARNE (b. 1982, Chicago) is a Los Angeles-based composer, singer and bandleader noted for his “voracious curiosity” (NewMusicBox), “tough edge and wildness of spirit,” and “fresh and muscular” music (The New York Times), who “writes with…technical assurance and imaginative scope” (San Francisco Chronicle). -

Concert Program Booklet 2016-2017

DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CARLETON COLLEGE CONCERT PROGRAM BOOKLET 2016-2017 NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA 2016-2017 CONCERT PROGRAMS CONCERT SERIES AND VISITING ARTISTS pgs. 8-52 CHRISTOPHER U. LIGHT LECTURESHIP I September 16 Composer Andrea Mazzariello, Mobius Percussion, & Nicola Melville, piano CHRISTOPHER U. LIGHT LECTURESHIP II September 17 Symmetry and Sharing film screening Featured artists Andrea Mazzariello & Mobius Percussion GUEST ARTIST CONCERT September 30 Dúo Mistral plays Debussy Featuring pianists Paulina Zamora & Karina Glasinovic WOODwaRD CONCERT SERIES October 16 Larry Archbold Concert and Colloquium FaculTY AND GUEST ARTIST CONCERT October 29 “Music of China” Featuring Spirit of Nature & the Carleton Chinese Music Ensemble GUEST ARTIST CONCERT January 20 The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra Featuring Jonathan Biss, piano & composer Sally Beamish GUEST ARTIST LECTURE February 1 Musicians from the Beijing Bamboo Orchestra LauDIE D. PORTER CONCERT SERIES February 9 MONTAGE: Great Film Composers and the Piano film screening Featuring Gloria Cheng, piano 2016-2017 CONCERT PROGRAMS CONCERT SERIES AND VISITING ARTISTS (Cont.) GUEST ARTIST CONCERT April 28 Malcolm Bilson, keyboard virtuoso ARTS @ CARLETON VISITING ARTISTS pgs. 53-57 THIRD COAST PERCUSSION April 11 Sponsored by Arts @ Carleton and the Department of Art and Art History FACULTY RECITALS pgs. 58-72 CONTEMPORARY VOICES FROM LATIN AMERICA January 15 Matthew McCright, piano Featuring Guest Artist Francesca Anderegg, violin CHINGLISH: Gao Hong, Chinese pipa April 7 HOMAGES: Nicola -

2011 – 2012 Hymns and Songs

ABOUT BNMI The Boston New Music Initiative is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization dedicated to maintaining an international network of composers, performers, conductors, directors, and champions of music in order to generate new music concerts, compositions, collaborations, and commissions. Incorporated in 2010, the organization aims to advance the careers of its members in the field of new music by serving as a resource for networking, commissioning, Nathan Lofton, Music Director collaboration, and programming. Jennifer Lester, Guest Conductor The Boston New Music Initiative, Inc. 2011 – 2012 2011-2012 Board of Directors Michael Anmuth (chair); Todd Minns; Erin Smith; Kirsten Volness Hymns and Songs 2011-2012 Staff Featuring the works of: Administration Artistic/Production Staff Timothy A. Davis, Chief Executive Officer Erin Smith, Artistic Director Curtis Minns, Chief Financial Officer Nathan Lofton, Music Director Lembit BEECHER Jeremy Spindler, Vice President Rebecca Smith, Production Manager N. Lincoln HANKS Kirsten Volness, Director of Publicity/Marketing Liora Holley, Orchestra Manager Jean Y. Foo, Director of Development Stephen Jean, Orchestra Librarian Ted HEARNE Sara Townsend, Event Coordinator Kyle Phipps, Stage Manager Jessica RUDMAN Nate Wakefield, Marketing Associate Jacob Richman, Media Specialist Mike SOLOMON Naoki Okoshi, Marketing Associate Nick Gleason, General Staff Aaron Kirschner, Membership Coordinator Jared Field, Licensing Coordinator Sid Richardson, General Staff Saturday, November 19, 2011 8:00 pm Pickman Hall Longy School of Music 27 Garden Street Cambridge, Massachusetts Concert 2 Season 3 The Boston New Music Initiative Concert Series 2 Become involved with BNMI! To join BNMI: To join our organization’s network of composers, performers, conductors, collaborators, and champions of new music, please visit our website (URL listed below). -

SOUND from the BENCH Music by Ted Hearne Conducted by Donald Nally

SOUND FROM THE BENCH Music by Ted Hearne conducted by Donald Nally Performed by The Crossing Katy Avery Michael Jones Jessica Beebe Heather Kayan Karen Blanchard Mark Laseter Steven Bradshaw Chelsea Lyons Colin Dill Maren Montalbano Micah Dingler Rebecca Myers Robert Eisentrout Becky Oehlers Allie Faulkner Daniel Schwartz Ryan Fleming Rebecca Siler Joanna Gates Daniel Spratlan Dimitri German Elisa Sutherland Steven Hyder Jason Weisinger with instrumentalists Taylor Levine, electric guitar James Moore, electric guitar Ron Wiltrout, drums/percussion lighting design by Bruce Steinberg sound design by Garth MacAleavey text for Sound from the Bench by Jena Osman produced by Beth Morrison Morrison Projects creative producer Beth Morrison general manager Jecca Barry production manager James Fry associate producer Mariel O’Connell company manager Liene Camarena Fogele Produced in association with The Crossing Special Thanks to Frederick Morrsion and Catherine Lord Sound from the Bench, an album recorded by Ted Hearne, Donald Nally and The Crossing and produced by Nick Tipp, will be released next month on Cantaloupe Music. See cantaloupemusic.com for more details. PROGRAM Consent (2014) Ripple (2012) Privilege (2010) 1. motive/mission 2. casino 3. burning tv song 4. they get it 5. we cannot leave [Break] Sound from the Bench (2014, rev. 2016) 1. How to throw your voice 2. Mouth piece 3. (Ch)oral argument 4. Simple surgery 5. When you hear ABOUT THE ARTISTS: TED HEARNE (b. 1982, Chicago) is a Los Angeles-based composer, singer and bandleader noted for his “voracious curiosity” (NewMusicBox), “tough edge and wildness of spirit,” and “fresh and muscular” music (The New York Times), who “writes with…technical assurance and imaginative scope” (San Francisco Chronicle). -

SFCMP Presents an Evening of Cage Variations with Special Guest Ted

Contact: Sheryl Lynn Thomas [email protected] (415) 633-8802 View Press Kits SFCMP PRESENTS AN EVENING OF CAGE VARIATIONS WITH SPECIAL GUEST TED HEARNE Concert Includes Works by Ted Hearne, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Molly Joyce, Timo Andres, and Ingram Marshall preceded by “How Music is Made” open rehearsal and composer talk with Ted Hearne SAN FRANCISCO (December 20, 2018) - San Francisco Contemporary Music Players (SFCMP) announces its January 18, 2019, six-work concert, including special guest 2018 Pulitzer Prize finalist, composer, and singer Ted Hearne. This concert is part of SFCMP’s ongoing in the LABORATORY concert series, which showcases large-ensemble contemporary works that push the boundaries of the concert experience. For this performance, we explore several points of connectivity along experimentalist paths, laid down by composers all seeking to fuse a variety of music forms and personal experiences into multi-faceted sonic narratives. An epigrammatic song by Charles Ives serves as a jumping-off point for Ted Hearne’s ‘The Cage’ Variations, a panoply of musical influence and memory that incorporates the work of numerous others in addition to his own. Hearne will join this special SFCMP concert as both a performer and a composer, singing the vocal portion of his variations while including an auto-tuning effect. His use of auto-tuning is as much for the specificity and curiosity of its sound as for its connection to our associations with its use in pop, hip-hop and mass media. Other featured pieces include works by Ingram Marshall, Molly Joyce, Timo Andres, and Mark-Anthony Turnage as they join together in further exploration of the theme - the direct interaction of live performers with pre-recorded sound materials from places across the globe.