Language Shift and Lexical Merger: a Case Study of Ìlàjẹ and Àpóị̀

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

Introduction Urban Reproductive Health

Family Planning Effort Index Ibadan, Ilorin, Abuja, and Kaduna FPE Nigeria 2011 Introduction Nigeria has a current population of 152 million with a growth rate of 3.2%, a Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) of 15.4 and a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 5.7. Nigeria plays an important role in the socio- political context of West Africa, since it constitutes 50.2% of the total population of the region (PRB 2009, DHS 2008). In response to the pattern of high growth rates, the National Policy on Population for Sustainable Development was launched in 2005. The policy recognized that population factors, social and economic development, and environmental issues are irrevocably interconnected and addressing them are critical to the achievement of sustainable development in Nigeria. The Nigerian population policy sets specific targets aimed at addressing high rates of population growth including a reduction in the annual national growth rate to 2% or lower by 2015, a reduction in the TFR of at least 0.6 children per woman every five years, and an increase in CPR of at least 2% points per year. However, Nigeria still has a 20% unmet need for family planning (NPC and ICF Macro, 2009). Family Planning was included in the fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG) as an indicator for tracking progress of improving maternal health. This concept of integrating family planning with maternal health services is the same approach that the Nigerian Ministry of Health is utilizing with messages related to family planning highlighting the links between utilization and reduced maternal mortality. However, continuing low levels of CPR and high levels of maternal mortality highlight the importance of an increased emphasis on family planning both within the context of maternal health and other health and social benefits. -

(IITA) Oyo Road, PMB 5320 Ibadan, Nigeria Regional Cocoa Symposium

TRAVEL ADVICE International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) Oyo Road, PMB 5320 Ibadan, Nigeria Regional Cocoa Symposium Contact at IITA: [email protected] CRIN contact: [email protected] WCF contact: [email protected] Before departure You need a valid passport, a visa (depending on your nationality), and a health certificate verifying an up-to-date yellow fever inoculation1. Citizens of countries belonging to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) are exempted from the visa requirement. Kindly be aware that Ibadan is located in the Humid Tropics and that malaria is endemic in the area. It is advised to dress accordingly and take doctor’s advice before traveling. Obtaining a Nigerian Visa Applications for visas can be made at any Nigerian Embassy, Consulate, or High Commission in your country of residence or the nearest to you. The website https://portal.immigration.gov.ng/visa/freshVisa can give you more information. The application process may be time consuming. IITA will generate an invitation and visa support letter that will accompany your request. It is also possible to arrange for a visa on arrival if you reside in a country where Nigeria has no legal representation; please contact us for that one. You cannot buy a visa at the airport on arrival! Arriving at Lagos Airport Murtala Mohammed International Airport, Ikeja, is the port of disembarkation. Representatives from IITA will meet you after the baggage collection area to take you to the IITA vehicles. Airport assistance is also available (on request) to take you through immigration, customs and checking-in at a cost of USD 40 including arrival and departures. -

Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard

The case of Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard Contact: Source: CIA factbook Laurent Fourchard Institut Francais de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA), University of Ibadan Po Box 21540, Oyo State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION: THE CITY A. URBAN CONTEXT 1. Overview of Nigeria: Economic and Social Trends in the 20th Century During the colonial period (end of the 19th century – agricultural sectors. The contribution of agriculture to 1960), the Nigerian economy depended mainly on agri- the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell from 60 percent cultural exports and on proceeds from the mining indus- in the 1960s to 31 percent by the early 1980s. try. Small-holder peasant farmers were responsible for Agricultural production declined because of inexpen- the production of cocoa, coffee, rubber and timber in the sive imports and heavy demand for construction labour Western Region, palm produce in the Eastern Region encouraged the migration of farm workers to towns and and cotton, groundnut, hides and skins in the Northern cities. Region. The major minerals were tin and columbite from From being a major agricultural net exporter in the the central plateau and from the Eastern Highlands. In 1960s and largely self-sufficient in food, Nigeria the decade after independence, Nigeria pursued a became a net importer of agricultural commodities. deliberate policy of import-substitution industrialisation, When oil revenues fell in 1982, the economy was left which led to the establishment of many light industries, with an unsustainable import and capital-intensive such as food processing, textiles and fabrication of production structure; and the national budget was dras- metal and plastic wares. -

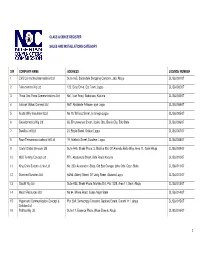

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Olubadan Centenary Anthology

1 Dedication This book is dedicated to His Royal Majesty Oba (Dr) Samuel Odulana, Odugade 1- An Icon of Peace and Justice All Rights Reserved © Ibadan Book Club - 2014 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication 2 Preface 5 Evolution in the unique system of selecting the Olubadan of Ibadan 6 Introduction 6 Ibadan‘s Unique System 7 Causative Factors of Longevity 9 Areas of Reform 11 A Bright Horizon Ahead 13 Origin of Ibadanland 14 Ibadan- A New Political Power in Yoruba Land 19 Olubadan 26 Ruling Lines 27 Accession Process 28 Today 28 List of Olubadan 29 Poems 35-41 Art Works 42-48 About Ibadan Book Club 48-51 4 PREFACE We thank God for the Gift of Long Life given to our Father, His Royal Majesty Oba (Dr) Samuel Odulana, Odugade 1. The memory of Baba will forever lingers in the memory of the sons and daughters of Ibadan land for his huge contributions and peaceful coexistence of Ibadan people. Ibadan is the citadel of literacy and literary art in Nigeria as it first accommodated the first literary Society ―Mbari Mayo‖ in Nigeria and the whole of Africa. We the members of the Society of Young Nigerian Writers and Ibadan Book Club congratulates our King, His Royal Majesty Oba (Dr) Samuel Odulana, Odugade 1 on his successful celebration of Baba‘s Centenary anniversary. We wish Baba more years ahead. Wole Adedoyin © 2014. 5 EVOLUTION IN THE UNIQUE SYSTEM OF SELECTING THE OLUBADAN OF IBADAN By Chief T.A. AKINYELE Introduction Each time an Olubadan is to be crowned many people who do not know the background history and the nature of the chieftaincy system in Ibadan have always wondered why Ibadan people choose to have very old men to lead them as their Oba and consequently almost every ten years a coronation ceremony occurs. -

Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba

Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba Suzanne Preston Blier rtists the world over shape knowledge and ancient works alongside diverse evidence on this center’s past material into works of unique historical and the time frame specific to when these sculptures were made. importance. The artists of ancient Ife, ances- In this way I bring art and history into direct engagement with tral home to the Yoruba and mythic birthplace each other, enriching both within this process. of gods and humans, clearly were interested in One of the most important events in ancient Ife history with creating works that could be read. Breaking respect to both the early arts and later era religious and political the symbolic code that lies behind the unique meanings of Ife’s traditions here was a devastating civil war pitting one group, the Aancient sculptures, however, has vexed scholars working on this supporters of Obatala (referencing today at once a god, a deity material for over a century. While much remains to be learned, pantheon, and the region’s autochthonous populations) against thanks to a better understanding of the larger corpus of ancient affiliates of Odudua (an opposing deity, religious pantheon, Ife arts and the history of this important southwestern Nigerian and newly arriving dynastic group). The Ikedu oral history text center, key aspects of this code can now be discerned. In this addressing Ife’s history (an annotated kings list transposed from article I explore how these arts both inform and are enriched by the early Ife dialect; Akinjogbin n.d.) indicates that it was during early Ife history and the leaders who shaped it.1 In addition to the reign of Ife’s 46th king—what appears to be two rulers prior core questions of art iconography and symbolism, I also address to the famous King Obalufon II (Ekenwa? Fig. -

UC Irvine Journal for Learning Through the Arts

UC Irvine Journal for Learning through the Arts Title UNITY IN DIVERSITY: THE PRESERVED ART WORKS OF THE VARIED PEOPLES OF ABEOKUTA FROM 1830 TO DATE Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2fp9m1q6 Journal Journal for Learning through the Arts, 16(1) Authors Ifeta, Chris Funke Idowu, Olatunji Adenle, John et al. Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.21977/D916138973 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Unity in Diversity: Preserved Art Works of Abeokuta from 1830 to Date and Developmental Trends * Chris Funke Ifeta, **Bukola Odesiri Ochei, *John Adenle, ***Olatunji Idowu, *Adekunle Temu Ifeta * Tai Solarin University of Education, Ijagun, Ijebu-Ode, Ogun State, Nigeria. **Faculty of Law, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria ** *University of Lagos, Lagos State Please address correspondence to funkeifeta @gmail.com additional contacts: [email protected] (Ochei); [email protected] (Adenle); [email protected] (Ifeta, A.) Abstract Much has been written on the history of Abeokuta and their artworks since their occupation of Abeokuta. Yoruba works of art are in museums and private collections abroad. Many museums in the Western part of Nigeria including the National Museum in Abeokuta also have works of art on display; however, much of these are not specific to Abeokuta. Writers on Abeokuta works of art include both foreign and Nigerian scholars. This study uses historical theory to study works of art collected and preserved on Abeokuta since inception of the Egba, Owu and Yewa (Egbado) occupation of the town and looks at implications for development in the 21st century. The study involved the collection of data from primary sources within Abeokuta in addition to secondary sources of information on varied works of art including Ifa and Ogboni paraphernalia. -

A Perception Study of Development Control Activities in Ibadan, Osogbo and Ado-Ekiti

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Olowoporoku, Oluwaseun; Daramola, Oluwole; Agbonta, Wilson; Ogunleye, John Article Urban jumble in three Nigerian cities: A perception study of development control activities in Ibadan, Osogbo and Ado-Ekiti Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES) Provided in Cooperation with: Opole University Suggested Citation: Olowoporoku, Oluwaseun; Daramola, Oluwole; Agbonta, Wilson; Ogunleye, John (2017) : Urban jumble in three Nigerian cities: A perception study of development control activities in Ibadan, Osogbo and Ado-Ekiti, Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES), ISSN 2081-8319, Opole University, Faculty of Economics, Opole, Vol. 17, Iss. 4, pp. 795-811, http://dx.doi.org/10.25167/ees.2017.44.10 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193043 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

28 Sustaining Aspects of Cultural Heritage

International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions Vol.6, No.1, pp.28-40, February 2018 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) SUSTAINING ASPECTS OF CULTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT IN NIGERIA: CASE STUDY OF WOODEN OBJECTS IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM IN ORON, NIGERIA Michael Abiodun Oyinloye Department of Fine and Applied Arts, OlabisiOnabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Nigeria ABSTRACT: The care and management of cultural, as well as natural heritage against wane, loss or damage is paramount to Cultural Resource Management. The system of caring and preserving objects and materials in the museum is through preventive conservation to ensure longer lifespan of the objects. This method involves housekeeping and daily inspection of objects in the store and galleries of the Museum in order to detect infection and deterioration. The study, therefore, examined types and functions of carved wooden objects, as well as methods and adequacies with a view to determining their effects at the National Museum in Oron, Nigeria. The study observed more than 3,000 collections in the store, galleries and courtyard of the museum, with about 80% of collections as wooden objects. It also takes cognisance of wooden objects in the museum as national treasure from ancient times as a benefit to our knowledge of tourists, researchers and coming generations. The study gives an overview of the activities of care in the National Museum Oron. It highlights the challenges faced by the museum. It concluded by imploring National Commission for Museums and Monuments in the country to come to the aid of Oron museum by providing conservation laboratory, modern equipment and facilities to improve the level of conservation. -

Ibadan Study of Ageing (Isa): Rationale and Methods

IBADAN STUDY OF AGEING (ISA): RATIONALE AND METHODS Oye Gureje Professor of Psychiatry University of Ibadan Nigeria Introduction • The Ibadan Study of Ageing consists of two components: – Baseline cross‐sectional study: conducted in 2003/2004 to determine the profile and availability of informal care for elderly persons in need of care – A longitudinal cohort study: conducted in three annual waves (2007 – 2009) to examine profile and determinants of successful aging – Both components are supported by the Wellcome Trust Setting… – Eight contiguous states in the south‐west and north‐ central regions of Nigeria • Population: > 25 million (representing 22% of the Nigerian population) • Predominant language is Yoruba (one of the three major Nigerian languages) Subjects… – Persons aged 65 years and over • Residing in households (i.e. non‐institutionalized) • Speak Yoruba, the study language • Able to undergo a face‐to‐face interview • Consenting Sampling • Selection of elderly respondents – Multistage cluster sampling • Local government areas • Enumeration areas (geographical units demarcated by the National Population Commission) • Households • (Stratification on the basis of state, size of local government areas) – One eligible person per household • Selected using the Kish method when > 1 in household • No replacement for refusals • Result of selection procedure – Sample: 2152 – Response: 74% Age distribution of the respondents compared with the general population by post‐stratification variables Age, yrs Unweighte Weighted National census* -

02. Ado and Ekiti Parapo Wars

European Journal of Political Science Studies ISSN: 2601 - 2766 ISSN-L: 2601 - 2766 Available on-line at: www.oapub.org/soc doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1117761 Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2017 ADO AND EKITI PARAPO WARS Soetan, Stephen Olayiwolai Department of History and International Studies, Ekiti State Suniversity, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti, Nigeria Abstract: The paper focuses on the roles of Ado Ekiti in the Ekiti Parapo war. The 19th century history of Yorubaland was characterized with series of wars and crises. The war which was a bold step to throw away the Ibadan hegemony over the eastern Yorubaland saw the coming together of all towns in the eastern Yorubaland, hence the appellation of Ekitiparapo. The coming together of the people however saw the absence of Ado Ekiti in the grand alliance. The reason for Ado Ekiti not participating in the war is highlighted here. This paper therefore examines the factors that are responsible for Ado Ekiti absence in the war. Keywords: Ekiti parapo, Ibadan, war, Eastern Yorubaland Introduction The Yoruba Ekiti Parapo War was an epic and chronic civil war between two powerful Yoruba confederate armies of mainly Western Yoruba and its Allies (Ibadan and its allies) and its Eastern Yoruba (Ijesha) Ekiti and the Igbomina Countries) The main action of the war took place in the North-East. It was a war that put an end to all manners of wars and semblance of war in Yorubaland. Indeed, it was a war for supremacy between Ilesha, Ekiti, Igbomina and Ibadan. It started on 30th July 1877. In the beginning of the nineteenth century, the old Oyo Empire which was on the verge of decay eventually collapsed under the onslaught of the Muslim Fulani Emirate established at Ilorin.