Privacy Sigma Riders, Brought to You by the Cisco Security and Trust Organization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St John's JCR ALTERNATIVE PROSPECTUS ? 08 E D I S N I

St John's JCR ALTERNATIVE PROSPECTUS ? 08 e d i s n i s ' t a h W Introduction to JCR My time at John’s so far has been like a movie. But as a A day in the life prospective student in your shoes I was under barrage from rumours of John’s “elitism”. Seriously look on any online forum Academia and it’s like googling Angelina Jolie and seeing “and Brad Pitt” Living in John's being suggested – always put together but in actual reality separate (certainly now in 2020). Whilst many may have Societies lamented the separation of the two movie stars, I certainly did Equality at John's not for the separation of John’s from its “elitism”, especially as Support a kid who’d grown up like most have in state schools. Applying to John's I find John’s student life progressive and exciting. It’s a community that’s as open and welcoming as it is close knit. Like Angelina, John’s is gorgeous but I hold that this college Will - 1st year Medic stands out above others for reasons beyond that. Its special because of the people who live and define it. Modern and dynamic, our student body is large. Hi, my name is Will, I study medicine at St John’s College and am the JCR Equal With that in mind I pass you, the reader, to the student of St Opportunities officer for 2020. Before you John’s. We’ve come together to give you a taste of our college dive into this alternative prospectus, I’d like life – written by students for students. -

National Life Stories an Oral History of British Science

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH SCIENCE Professor Michael McIntyre Interviewed by Paul Merchant C1379/72 Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C1379/72 Collection title: An Oral History of British Science Interviewee’s surname: McIntyre Title: Professor Interviewee’s forename: Michael Sex: Male Occupation: Applied Date and place of birth: 28/7/1941, Sydney, mathematician Australia Mother’s occupation: / Father’s occupation: Neurophysiologist Dates of recording, tracks (from – to): 28/03/12 (track 1-3), 29/03/12 (track 4-6), 30/03/12 (track 7-8) Location of interview: Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge Name of interviewer: Dr Paul Merchant Type of recorder: Marantz PMD661 Recording format : WAV 24 bit 48kHz Total no. of tracks: 8 Mono/Stereo: Stereo Total Duration: 9:03:31 Additional material: The interview transcripts for McIntyre’s mother, Anne, father, Archibald Keverall and aunt, Anne Edgeworth are available for public access. Please contact the oral history section for more details. -

Aaa Worldwise

AAA FALL 2017 WORLDWISE Route 66 Revival p. 32 Dressing for Access p. 38 South Africa: A Tale of Two Cities p. 48 TWO OF A KIND: THE ORIGINAL COLLEGE TOWNS Cambridge MASSACHUSETTS Just north of Boston and home to Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, this city oozes intellectualism and college spirit. COURTESY OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY HARVARD OF COURTESY Harvard and the Charles River STAY SEE When celebs come to Harvard, they’re put up at Harvard University’s three venerable art the AAA Four Diamond Charles Hotel. Just museums were brought under one roof in minutes from Harvard Yard, The Charles has a 2014 and collectively dubbed the Harvard well-stocked in-house library and one of the best Art Museums. Their collections include some breakfasts in town at Henrietta’s Table. The 250,000 art works dating from ancient times to 31-room luxury Hotel Veritas—described by the present and spanning the globe. The MIT a GQ magazine review as “a classic Victorian Museum, not surprisingly, focuses on science and mansion that went to Art Deco finishing technology. It includes the Polaroid Historical school”—boasts 24-hour concierge service Collection of cameras and photographs, the COURTESY OF HOTEL VERITAS HOTEL OF COURTESY and a location in Harvard Square. Those who MIT Robotics Collection and the world’s Hotel Veritas prefer to bed down near the Massachusetts most comprehensive holography collection. Institute of Technology (MIT) should check in Beyond the universities, visit the Longfellow at The Kendall Hotel, which brings boutique House–Washington’s Headquarters, the accommodations to a converted 19th-century preserved, furnished home of 19th-century poet firehouse. -

Jesus College May Ball (Cambridge) Privacy Notice Last Modified March

Jesus College May Ball (Cambridge) Privacy Notice Last modified March 2019 About this Privacy Notice In this Privacy Notice, references to “we”, “us” and “our” are to Jesus College May Ball (Cambridge). We are committed to protecting your personal data. Personal data is any information relating to an identifiable living person who can be directly or indirectly identified by reference to this data. This privacy notice relates to our use of any personal data that you directly provide us. We will comply with data protection law which requires that personal data we hold about you is: ● used lawfully, fairly and in a transparent way; ● collected only for valid purposes that we have clearly explained to you and not used in any way incompatible with those purposes; ● relevant to the purposes we have told you about and limited only to those purposes; ● accurate and kept up to date; ● kept only as long as necessary for the purposes we have told you about; ● kept securely. This privacy notice will therefore inform you as to who we are, what personal data we collect, the purposes for which we use it, for how long we retain it and how we keep it secure, your rights in relation to you personal data, and how you can contact us to discuss, query or obtain details of the personal data we hold about you. Topics 1. Who we are 2. Whose personal data we process 3. Why we process your personal data 4. Personal data sources 5. How we will inform you about our privacy notice 6. -

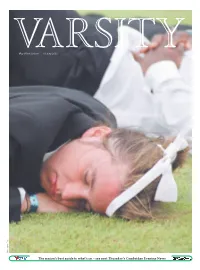

In Girton Varsity Exclusively Reveals Allegations of Student Attack During the Early Hours of March 17Th

GENERAL ELECTION 2005 - Varsity meets all your parliamentary candidates -PAGES 4 & 5 - Your Vote: Comment & Analysis -PAGES 5, 10, 18 - Howard Flight, Tessa Jowell & Lord McNally -PAGES 4 & 5 No. 619 The Independent Cambridge Student Newspaper since 1947 Friday April 29, 2005 Six undergraduates arrested over “serious sexual assault” in Girton Varsity exclusively reveals allegations of student attack during the early hours of March 17th Varsity News Reporter end-of-term bop with the title morning of the 17th and have crime scene. been careful to keep the inci- tioned by the police. They of “Rumble in the Jungle”, now been released on bail. The incident is alleged to dent discreet. No announce- have since been released on organised on March 16th by The individuals accused have occured during the early ment of the event has yet been bail pending further question- POLICE OFFICERS are the Girton College JCR. were seen returning to Girton hours in central Girton made to Girton students. ing at a later date.” investigating a report of a very Varsity has chosen not to dis- during the early hours of the College accommodation. Cambridge University Press The six male individuals serious sexual assault alleged close the names of the under- 17th wearing police overalls, Neighbouring students were Office confirmed that have been bailed to return to to have taken place in Girton graduate victim or those of his creating speculation that their particularly shocked at the “Cambridgeshire police were Parkside Police Station on College during the early hours six alleged male attackers. clothes had been confiscated fact that the event is said to called to an alleged incident at Thursday May 5th. -

Suicide Sunday Faces Police Clampdown

VarsiTV.co.uk Festival previewp7 Fashionp8-9 Check out Forget Glasto be the envy of A taste of Caesaran your frends wth the help of our thngs to Sunday round-up of edgy events come some Stores 20s-style fun onlne now n the sun FRIDAY MAY 14TH 2010 THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NESPAPER SINCE 1947 ISSUE NO 718 | VARSITY.CO.UK CAMBRIDGE HUMANITARIAN CENTRE 6 Tabs in Suicide Sunday Cameron’s faces police cabinet clampdown OAA IDDII Six out of 22 of David Cameron’s new cabinet members are Cam- bridge alumni. Authortes to restrct ‘rresponsble’ Nick Clegg, the Deputy Prime drnks o ers Minister, read Social Anthropol- ogy at Robinson. During his time at a person’s mouth, thereby banning Cambridge, Clegg reportedly acted IZAT IGG the popular drinking game known as alongside Helena Bonham Carter ‘dentist’s chair’, a traditional fi xture and Sam Mendes. Cambridge end-of-term drinking at Suicide Sunday events all over Clegg is also said to have been parties are facing a potential police Cambridge. a member of the Cambridge Uni- clampdown after a series of drunken Peter Sinclair, Cambridgeshire versity Conservative Association incidents last year. Police’s Licensing Offi cer, cautioned (CUCA) . Cambridge police have issued students to be practice responsible Also involved with CUCA during direct warnings to organisers of drinking and keep their personal his time here was Ken Clarke, the undergraduate drinking societies safety in mind. Justice Secretary, who served as and other student events that they According to PC Sinclair, “Clearly chairman of the society. Clarke read could risk breaking the law. -

<4R^~?Z*£Iht DUTIFUL Th*^

PRICE 25 CENTS. JBlKATJTOirkH.Y H1LIL terser IRAKIS ID. <4r^~?z*£iHt <*s wa k. \ ^ ^ r4^ ^ t5*fC 'o I w , rt& DUTIFUL tH*^, vf BY s • NEW-YORK • v.:-- ill. J. UurgcB0, 22 2m\ ttvul §j] TH E LIFE AND GENIUS OF IIHMI no ffc»8erk: IU. 5. Bttrge*0, 22 Sinn 0trett 0* 4 LIFE AND GENIUS OF JENNY LIND. IN writing a memoir of this distinguished illness sho sought consolation from airs of a aongstress, whose fame has extended over the plaintive or melancholy nature. In fact, sing- whole civilized world, we are limited to fewer Ing might have been called the passion of her facts than the generality of biographers are, existence. When nine years of age she was when giving details relative to persons who, remarkably forward ill mind—so much so, like our fair subject, have achcived eminence as to be considered an extraordinary child. as public performers. This is easily ac But she was neither strong nor beautiful in counted for, by the different 's be features, though her face then, as well as it tween M . • .ii,l ai,d the majority now is, was character: ,,1 by an expression of her professional brothers and sisters, for of more than re beauty, and which has while they have aaeningiy availed them be, n frequently noticed in those persons •ry opportunity that preaentod it gifted by nature with a high degree of ge obtrude, iii a purely personal point of view- nius. world, the. with remarkable good 1'ortimatcly for the future sonirstress, and icnt, has maintained a dignl- fortunately too, for the world who were to he letireincnt; at be has charmed by llcr powers, a .Madam lamdbcrg honors and the plaudits that have heard the youthful Jenny Lind sing. -

Fourth Week Bulletin College Notices 1. VOTER

Fourth Week Bulletin College notices 1. VOTER REGISTRATION 2. Clare College, Cambridge - May Ball Ticket Offer Events 1. Regent's Fling Bar Committee 2. Oxford Africa Conference 2017 3. The 2 Trillionth Tonne: Consequences of Severe Climate Change in 2100 Arts and journalism 1. EMS production - Merrily We Roll along College notices 1. VOTER REGISTRATION Unless you’ve registered to vote since July 2016 – you will not be able to vote in the 2017 General Election!! Registering online takes less than 5 minutes – do it here now: gov.uk/register- to-vote If you want to check if you are registered to vote in Oxford, you can ring the City Council on 01865 249811 2. Clare College, Cambridge - May Ball Ticket Offer “My name is Leo, and I’m the President of the Clare May Ball in Cambridge this year, to take place on 19th June. I’ve been is talks with Eoin, the JCR president of Oriel College, Clare's sister college, and I offered them some tickets to attend the ball. He mentioned that his college was quite close with yours. Around 20 Oriel students have taken up the offer, however in order to fill a bus, we would to find 30 more students from Oxford who wanted to come to our ball too. I’m therefore writing to offer students from your college the chance to purchase tickets to the Clare May Ball 2017. With unlimited food from around the world, drinks flowing all night, 4 music stages and much more, this ball is more like a one night festival, and is set to be a brilliant night. -

The Representations of Stephen Hawking in the Biographical Movies

Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Educação em Ciências https://doi.org/10.28976/1984-2686rbpec2021u195224 The Representations of Stephen Hawking in the Biographical Movies João Fernandes, Guilherme da Silva Lima, Orlando Aguiar Jr. Keywords Abstract This article aims to analyze two biographical films of Stephen Hawking; Stephen Hawking in order to identify the representations of the Representation of scientist present in cinematographic works. For this, the investigation scientist; was based on film analysis and categorization following the main Movies; representations identified in the literature. The analysis identified the Scientific culture. most common representations present in the scenes and sequences in which the protagonist acted, taking into account the context for certain actions of the scientist. The results indicated that the analyzed works, which belong to a biographical genre, are also bound to permeate stereotypes that contribute to a distorted view of the scientist and scientific work, just as it happens in other cinematic genres. Introduction Science correlates with several different spheres of human culture, in a way that it is possible to find literary, plastic, scenic and cinematic works that make reference to the scientific universe. Such references are not based exclusively on specific issues of science and technology culture (STC); quite the contrary, they can appropriate themes, processes, languages, history, among other scientific and technological elements. This work considers as elements of scientific culture all human productions that interact with activities, processes, concepts, history and any other aspects of scientific and technological activity, even when produced in frontier territories, such as science fiction. Interfaces between STC and art occur for several reasons, among which we highlight both the interest of society in scientific themes and the appropriation of science and technology themes by the cultural industry. -

Cal Poly Magazine, Fall 1997

) I .r ~ '- r ~~ Fall 1997. Vol 1. Issue 1 '..--... EDITOR'S NOTES elcome to the inaugural issue of Cal Poly Carruth Goes to Washington"), in interviews of three Magazine, which replaces Cal Poly Today freshmen completing their first year ("Making the W with a new format and a fresh look at the Most of Year One: Bubba, Sarah and Matt on Their university's traditions, current pursuits, and future Own"), and in "University News" and "Alumni directions. News" stories. This first issue reexamines Cal Poly's special The magazine you hold is itself emblematic of approach to applied research, and highlights the Cal Poly's learn-by-doing credo. Not only has it been learn-by-doing experience that informs the studies printed by the student-operated University Graphic of all Cal Poly students. In our main feature, Systems, but our own staff has developed expertise "The Practical Scholar: Balancing Research and in new areas. Over many months we have planned, Learning," we report how students collect written, edited, and produced a publication that data for a California toll-road project, create attempts to blend the best of the past with a more 3-D videos in an art and design computer dynamic approach to campus news, resulting in a class, and act as marketing consultants for a variety of design innovations. local bicycle-touring company. "From the President," a column by President Hands-on learning is also the recurring motif Warren J. Baker, will run as an occasional feature, and in our open letter from a White House intern ("Ms. -

May Week Review 2003

May Week Review 19 June 2003 Christopher Tidy The region’s best guide to what’s on – see next Thursday’s Cambridge Evening News 19 June 2003 May Week Review A www.varsity.co.uk Mick Heyes Mick May Week 02 Madness and messiness Every year at around this time I find myself asking the same questions: why can’t Tim win Wimbledon, why does alcohol hurt so much and why didn’t I spend more of my time in the UL rather than in a dingy underground club? Another of my annual May Week mindsets is my Finesse Fantasy. Whilst imprisoning myself in the library for six weeks solid, I managed to construct wild illusions of myself floating around Trinity May Ball in the style of a Grecian goddess; making the boys crazy and the girls sick with envy. In reality, as I lurched and stumbled home, like a cow in the latter stages of BSE, wearing my date’s shoes and hitching my dress up above my knees, it occurred to me that I might be slightly delusional. What’s more striking though is how this kind of blind belief and optimism seems to permeate our culture. We live in a world where Darius can win fame and fortune, women aspire to the computer-enhanced images in their magazines and the winner of Big Brother is awarded twenty pages of tabloid coverage along with vast sums of money. It’s hard- ly surprising then that we tend to instil belief in our fantasies, despite our past fail- ures and awareness of our current situations. -

CHRIST's COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE Christs.Cam.Ac.Uk

CHRIST'S COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE CATALOGUE OF FELLOWS’ PAPERS Last updated 31 March 2020 by John Wagstaff 1 CONTENTS Box Number 1. Fragments found during the restoration of the Master's Lodge + Bible Box 2. Fragments and photocopies of music 3. Letter from Robert Hardy to his son Samuel 4. Photocopies of the title pages and dedications of ‘A Digest or Harmonie...’ W. Perkins 5. Facsimile of the handwriting of Lady Margaret (framed in Bodley Library) 6. MSS of ‘The Foundation of the University of Cambridge’ 1620 John Scott 7. Extract from the College “Admission Book” showing the entry of John Milton facsimile) 8. Milton autographs: three original documents 9. Letter from Mrs. R. Gurney 10. Letter from Henry Ellis to Thomas G. Cullum 11. Facsimile of the MS of Milton's Minor Poems 12. Thomas Hollis & Milton 13. Notes on Early Editions of Paradise Lost by C. Lofft 14. Copy of a letter from W.W. Torrington 15. Milton Tercentenary: Visitors' Book 16. Milton Tercentenary: miscellaneous material, (including "scrapbook") 17. Milton Tercentenary: miscellaneous documents 18. MS of a 17th century sermon by Alsop? 19. Receipt for a contribution by Sir Justinian Isham signed by M. Honywood 20. MS of ‘Some Account of Dr. More's Works’ by Richard Ward 21. Letters addressed to Dr. More and Dr. Ward (inter al.) 22. Historical tracts: 17th. century Italian MS 23. List of MSS in an unidentified hand 24. Three letters from Dr. John Covel to John Roades 25. MS copy of works by Prof. Nicholas Saunderson [in MSS safe] + article on N.S.