Merger Control 2018 Seventh Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competition Bites – South-East Asia & Beyond

Client Update 2018 January Regional Competition Competition Bites – South-East Asia & Beyond Introduction Welcome to the latest edition of our competition law updates, which captures important developments in the last quarter of 2017, in South-East Asia and beyond. The last quarter has been marked by several international mergers that have been scrutinised by competition authorities in various jurisdictions, with Singapore becoming even more active. A number of mergers are being reviewed in Singapore, with some moved into a Phase 2. Separately, the Department of Justice in the US has moved to block the AT&T/Time Warner merger, while the merger has been cleared in Brazil subject to certain behavioural remedies. In Europe, eagerly awaited decisions in the internet and technology sector have been released. In particular, the European Court of Justice in its Coty decision has now confirmed that it may be permissible under certain circumstances for businesses to ban internet sales on third party platforms. The German Federal Cartel Office has also preliminarily indicated that Facebook’s collection and processing of user data could amount to an abuse of dominance. The quarter has also seen developments to the competition law regime in several countries. Amongst others, Philippines has issued its Rules on Merger Procedure, and has consulted on its draft merger notification threshold guidelines. Amendments to Australia’s Competition and Consumer Act 2010 has also entered into force, and changes to Singapore’s and South Africa’s Competition Acts are currently being consulted on. The Rajah & Tann Asia Competition & Trade Practice, which spans South-East Asia, continues to grow from strength to strength, alongside regulators who continue to be or have become more active, including in the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam. -

The Impact of the New Substantive Test in European Merger Control

April 2006 European Competition Journal 9 A New Test in European Merger Control THE IMPACT OF THE NEW SUBSTANTIVE TEST IN EUROPEAN MERGER CONTROL LARS-HENDRIK RÖLLER AND MIGUEL DE LA MANO* A. INTRODUCTION After a two-year review process, the European Commission adopted on 1 May 2004 a new Merger Regulation,1 replacing the old EU Merger Regulation of 1990. In addition, guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers were issued.2 During this review process, one of the most controversial and intensively debated issues surrounding the future regime of European merger control was the new substantive test, the so-called SIEC (“significant impediment of effective competition”) test. This paper addresses the issue of whether the new merger test has made any difference in the way the Commission evaluates the competitive effects of mergers. We approach this question by reviewing the main arguments of why the test was changed and discuss the anticipated impact. It is argued that the new test can be expected to increase both the accuracy and effectiveness of merger control in two ways: first, it may close a gap in enforcement, which may have led to underenforcement in the past; and secondly, it may add to clarity by eliminating ambiguities regarding the interpretation of the old test, which possibly led to overenforcement in some cases. The remainder of the paper looks at the evidence available to date. We review a number of cases and ask in what way—if any—the new merger regime has made a difference. In particular, we ask whether there is any evidence of the above issues of under- and overenforcement. -

Merger Control 2021

Merger Control 2021 A practical cross-border insight into merger control issues 17th Edition Featuring contributions from: Advokatfirmaet Grette AS Drew & Napier LLC Norton Rose Fulbright South Africa Inc AlixPartners ELIG Gürkaynak Attorneys-at-Law OLIVARES ALRUD Law Firm Hannes Snellman Attorneys Ltd Pinheiro Neto Advogados AMW & Co. Legal Practitioners L&L Partners Law Offices Portolano Cavallo AnesuBryan & David Lee and Li, Attorneys-at-Law PUNUKA Attorneys & Solicitors Arthur Cox LNT & Partners Schellenberg Wittmer Ltd Ashurst LLP MinterEllison Schoenherr Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP Moravčević, Vojnović i Partneri AOD Beograd in Shin & Kim LLC BUNTSCHECK Rechtsanwaltsgesellschaft mbH cooperation with Schoenherr Sidley Austin LLP DeHeng Law Offices MPR Partners | Maravela, Popescu & Asociații URBAN STEINECKER GAŠPEREC BOŠANSKÝ Dittmar & Indrenius MSB Associates Zdolšek Attorneys at law DORDA Rechtsanwälte GmbH Nagashima Ohno & Tsunematsu Table of Contents Expert Chapters Reform or Revolution? The Approach to Assessing Digital Mergers 1 David Wirth & Nigel Parr, Ashurst LLP The Trend Towards Increasing Intervention in UK Merger Control and Cases that Buck the Trend 9 Ben Forbes, Felix Hammeke & Mat Hughes, AlixPartners Q&A Chapters Albania Japan 18 Schoenherr: Srđana Petronijević, Danijel Stevanović 182 Nagashima Ohno & Tsunematsu: Ryohei Tanaka & & Jelena Obradović Kota Suzuki Australia Korea 27 MinterEllison: Geoff Carter & Miranda Noble 191 Shin & Kim LLC: John H. Choi & Sangdon Lee Austria Mexico 36 DORDA Rechtsanwälte GmbH: Heinrich -

Seven & I Holdings' Market Share in Japan

Financial Data of Seven & i Holdings’ Major Retailers in Japan Market Share in Japan Major Group Companies’ Market Share in Japan ( Nonconsolidated ) In the top 5 for total store sales at convenience stores FY00 Share (Billions of yen) (%) Convenience stores total market ,1.1 100.0 Others Ministop 1.% 1 Seven-Eleven Japan 2,533.5 34.1 .% Seven-Eleven Japan Lawson 1,. 1. 34.1% Circle K Sunkus 11.% FamilyMart 1,0. 1. Circle K Sunkus . 11. FamilyMart Lawson 1.% 1.% Ministop .1 . Top Combined ,11. In the top 5 for net sales at superstores FY00 Share (Billions of yen) (%) Superstores total market 1,9. 100.0 AEON 1.% 1 AEON 1,. 1. Ito-Yokado 2 Ito-Yokado 1,487.4 11.8 11.8% Others .0% Daiei .9 . Daiei .% UNY 9. UNY .% Seiyu Seiyu . .% Top Combined ,0. .0 In the top 5 for net sales at department stores FY00 Share (Billions of yen) (%) Department stores total market ,1.0 100.0 Takashimaya 9.% Mitsukoshi 1 Takashimaya . 9. .% Sogo 5.7% Mitsukoshi 9. Others Daimaru 3 Sogo 494.3 5.7 .1% .% Seibu Daimaru 0. 5.3% 5 Seibu 459.0 5.3 Top Combined ,00.1 .9 Source: 1. The Current Survey of Commerce (Japan Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) . Public information from each company 38 Financial Data of Major Retailers in Japan Convenience Stores Total store sales (Millions of yen) Gross margin (%) ,00,000 ,000,000 1,00,000 0 1,000,000 00,000 0 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 FY00 Seven-Eleven Japan ,11,01 ,1,9 ,,1 ,0, ,9, ,, Seven-Eleven Japan 0. -

Prohibition Criteria in Merger Control – Dominant Position Versus Substantial Lessening of Competition?

Prohibition Criteria in Merger Control – Dominant Position versus Substantial Lessening of Competition? - Discussion Paper - Bundeskartellamt Discussion paper for the meeting of the Working Group on Competition Law1 on 8 and 9 October 2001 Prohibition Criteria in Merger Control - Dominant Position versus Substantial Lessening of Competition? translated version 1 Each year in autumn the Bundeskartellamt invites the Working Group on Competition Law, a group of university professors from faculties of law and economics, to participate in a two-day discussion on a current issue relating to competition policy or competition law. As the basis for their discussion the participants receive a working paper prepared by the Bundeskartellamt in advance of the conference. The present document contains the working paper prepared for the 2001 conference as well as a brief summary of the conclusions of the conference. - I - TABLE OF CONTENTS page A. Introduction 1 B. Concepts for the evaluation of mergers 2 I. Germany 2 II. European Union 4 III. United States 6 IV. Australia 10 V. United Kingdom / New Zealand 11 VI. Intermediate result 13 C. Evaluation of "problematic" mergers in practice 15 I. Oligopolies 15 1. Economic background 16 2. Evaluation in practice 17 3. Intermediate result 23 II. Vertical integration 24 1. Economic background 24 2. Evaluation in practice 25 3. Intermediate result 28 III. Conglomerate mergers 29 1. Economic background 29 2. Evaluation in practice 30 3. Intermediate result 33 D. Conclusions 34 ANNEX: Evaluation criteria in merger control II BIBLIOGRAPHY VI ABBREVIATIONS X - 1 - A. Introduction The preconditions for prohibiting company mergers are completely identical in only a few legal systems. -

China: Retail Foods

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/28/2017 GAIN Report Number: GAIN0036 China - Peoples Republic of Retail Foods Increasing Change and Competition but Strong Growth Presents Plenty of Opportunities for U.S. Food Exports Approved By: Christopher Bielecki Prepared By: USDA China Staff Report Highlights: China remains one of the most dynamic retail markets in the world, and offers great opportunities for U.S. food exporters. Exporters should be aware of several new trends that are changing China’s retail landscape. Imported food consumption growth is shifting from China’s major coastal metropolitan areas (e.g., Shanghai; Beijing) to dozens of emerging market cities. China is also experimenting with new retail models, such as 24-hour unstaffed convenience stores and expanded mobile payment platforms. E-commerce sales continue to grow, but major e-commerce retailers are competing for shrinking numbers of new consumers. We caution U.S. exporters not to consider China as a single retail market. Over the past 10 years, the Chinese middle-class has grown larger and more diverse, and China has become a collection of 1 niche markets separated by geography, culture, cuisine, demographics, and commercial trends. Competition for these markets has become fierce. Shanghai and the surrounding region continues to lead national retail trends, however Beijing and Guangzhou are also important centers of retail innovation. Chengdu and Shenyang are two key cities leading China’s economic expansion into international trade and commerce. -

1 September 29, 2017 ITOCHU Corporation (Code No. 8001, Tokyo

This document is an English translation September 29, 2017 of a statement written initially in Japanese. The Japanese original should be considered as the primary version. ITOCHU Corporation (Code No. 8001, Tokyo Stock Exchange 1st Section) Representative Director and President: Masahiro Okafuji Contact: Kazuaki Yamaguchi General Manager, Investor Relations Department (TEL. +81-3-3497-7295) Announcement in Relation to Commencement of Joint Tender Offer Bid for Share Certificates of Pocket Card Co., Ltd. (Code No. 8519) by a Wholly Owned Subsidiary of ITOCHU Corporation As announced in the press releases, “Announcement in Relation to Commencement of Joint Tender Offer Bid for Share Certificates of Pocket Card Co., Ltd. (Code No. 8519) by a Wholly Owned Subsidiary of ITOCHU Corporation,” dated August 3, 2017, and “Announcement in Relation to Determination of Tender Offeror in Joint Tender Offer Bid for Share Certificates of Pocket Card Co., Ltd. (Code No. 8519) by a Wholly Owned Subsidiary of FamilyMart,” dated today, it has been determined that GIT Corporation (Head office: Minato-ku, Tokyo; Representative Director and President : Kazuhiro Nakano; hereinafter referred to as “GIT”), a wholly owned subsidiary of ITOCHU Corporation (hereinafter referred to as “ITOCHU”) and BSS Co., Ltd. (Head Office: Toshima-ku, Tokyo; President & Chief Executive Officer: Hiroaki Tamamaki; hereinafter referred to as “BSS”), a wholly owned subsidiary of FamilyMart Co., Ltd. (Head office: Toshima-ku, Tokyo; President & Chief Executive Officer: Takashi Sawada; hereinafter referred to as “FamilyMart”), will jointly acquire common shares of Pocket Card Co., Ltd. (Code No. 8519, Tokyo Stock Exchange, 1st Section) through a tender offer (hereinafter referred to as “Tender Offer”) stipulated in the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (Act No.25 of 1948; including revisions thereafter). -

The Merger Control Review

[ Exclusively for: Suncica Vaglenarova | 09-Sep-15, 07:52 AM ] ©The Law Reviews The MergerThe Control Review Merger Control Review Sixth Edition Editor Ilene Knable Gotts Law Business Research The Merger Control Review The Merger Control Review Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. This article was first published in The Merger Control Review - Edition 6 (published in July 2015 – editor Ilene Knable Gotts) For further information please email [email protected] The Merger Control Review Sixth Edition Editor Ilene Knable Gotts Law Business Research Ltd PUBLISHER Gideon Roberton BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Nick Barette SENIOR ACCOUNT MANAGERS Katherine Jablonowska, Thomas Lee, Felicity Bown ACCOUNT MANAGER Joel Woods PUBLISHING MANAGER Lucy Brewer MARKETING ASSISTANT Rebecca Mogridge EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Shani Bans HEAD OF PRODUCTION Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne Borthwick SUBEDITOR Caroline Herbert MANAGING DIRECTOR Richard Davey Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 2015 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided is accurate as of July 2015, be advised that this is a developing area. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to Law Business Research, at the address above. -

Global Consumer Survey List of Brands June 2018

Global Consumer Survey List of Brands June 2018 Brand Global Consumer Indicator Countries 11pingtai Purchase of online video games by brand / China stores (past 12 months) 1688.com Online purchase channels by store brand China (past 12 months) 1Hai Online car rental bookings by provider (past China 12 months) 1qianbao Usage of mobile payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 1qianbao Usage of online payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 2Checkout Usage of online payment methods by brand Austria, Canada, Germany, (past 12 months) Switzerland, United Kingdom, USA 7switch Purchase of eBooks by provider (past 12 France months) 99Bill Usage of mobile payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 99Bill Usage of online payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) A&O Grocery shopping channels by store brand Italy A1 Smart Home Ownership of smart home devices by brand Austria Abanca Primary bank by provider Spain Abarth Primarily used car by brand all countries Ab-in-den-urlaub Online package holiday bookings by provider Austria, Germany, (past 12 months) Switzerland Academic Singles Usage of online dating by provider (past 12 Italy months) AccorHotels Online hotel bookings by provider (past 12 France months) Ace Rent-A-Car Online car rental bookings by provider (past United Kingdom, USA 12 months) Acura Primarily used car by brand all countries ADA Online car rental bookings by provider (past France 12 months) ADEG Grocery shopping channels by store brand Austria adidas Ownership of eHealth trackers / smart watches Germany by brand adidas Purchase of apparel by brand Austria, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Statista Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. -

Wikipedia List of Convenience Stores

List of convenience stores From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of convenience stores organized by geographical location. Stores are grouped by the lowest heading that contains all locales in which the brands have significant presence. NOTE: These are not ALL the stores that exist, but a good list for potential investors to research which ones are publicly traded and can research stock charts back to 10 years on Nasdaq.com or other related websites. [edit ] Multinational • 7-Eleven • Circle K [edit ] North America Grouping is by country or united States Census Bureau regional division . [edit ] Canada • Alimentation Couche-Tard • Beckers Milk • Circle K • Couch-Tard • Max • Provi-Soir • Needs Convenience • Hasty Market , operates in Ontario, Canada • 7-Eleven • Quickie ( [1] ) [edit ] Mexico • Oxxo • 7-Eleven • Super City (store) • Extra • 7/24 • Farmacias Guadalajara [edit ] United States • 1st Stop at Phillips 66 gas stations • 7-Eleven • Acme Express gas stations/convenience stores • ampm at ARCO gas stations • Albertsons Express gas stations/convenience stores • Allsup's • AmeriStop Food Mart • A-Plus at Sunoco gas stations • A-Z Mart • Bill's Superette • BreakTime former oneer conoco]] gas stations • Cenex /NuWay • Circle K • CoGo's • Convenient Food Marts • Corner Store at Valero and Diamond Shamrock gas stations • Crunch Time • Cumberland Farms • Dari Mart , based in the Willamette Valley, Oregon Dion's Quik Marts (South Florida and the Florida Keys) • Express Mart • Exxon • Express Lane • ExtraMile at -

Familymart, Where You Are One of the Family

FamilyMart, Where You Are One of the Family Sustainability Report 2019 1 Contents Contents / Editorial Policy Contents Materiality 2 34 Evolving as a Regional Revitalization Base Close to People 1 Contents / Editorial Policy 35 Contributing to Create Safe, Secure Neighborhoods 2 Corporate Message Editorial Policy 38 Supporting the Development of the Next Generation / Responding to an Aging Society About this Report 3 Top Message Materiality 3 This is the Sustainability Report of FamilyMart Co., Ltd. Becoming a 42 Creating Safe and Reliable Products and Services to Bring In this publication, we report on the entire range of sustainability initiatives Chain More Convenience and Richness to Everyday Life that FamilyMart pursues to ensure we continue growing sustainably with society. Beloved by the 43 Improvement of Customer Satisfaction / Promotion of Digitalization Before issuing this report, we ask the head of our Society & Environment to Improve Convenience Committee, an advisory body to our Representative Director and President, to Community Than 45 Provision of Products and Services to Improve Health and Well-being Any Other review it. Materiality 4 Readers should note that the subject of our reporting is different than in 48 Working with Suppliers to Pursue a Sustainable Supply Chain earlier years. This is because in September 2019, we effected organizational Sustainability Management 49 Fair and Transparent Business / changes to an operating company that runs convenience store business as our 7 Value Creation Model Building Good Relationships -

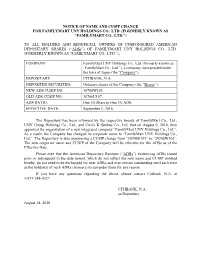

Notice of Name and Cusip Change for Familymart Uny Holdings Co., Ltd

NOTICE OF NAME AND CUSIP CHANGE FOR FAMILYMART UNY HOLDINGS CO., LTD. (FORMERLY KNOWN AS “FAMILYMART CO., LTD.”) TO ALL HOLDERS AND BENEFICIAL OWNERS OF UNSPONSORED AMERICAN DEPOSITARY SHARES (“ADSs”) OF FAMILYMART UNY HOLDINGS CO., LTD. (FORMERLY KNOWN AS “FAMILYMART CO., LTD.”), COMPANY: FamilyMart UNY Holdings Co., Ltd. (formerly known as “FamilyMart Co., Ltd.”), a company incorporated under the laws of Japan (the “Company”). DEPOSITARY: CITIBANK, N.A. DEPOSITED SECURITIES: Ordinary shares of the Company (the “Shares”). NEW ADS CUSIP NO: 30706W103. OLD ADS CUSIP NO: 30706U107. ADS RATIO: One (1) Share to One (1) ADS. EFFECTIVE DATE: September 1, 2016. The Depositary has been informed by the respective boards of FamilyMart Co., Ltd., UNY Group Holdings Co., Ltd., and Circle K Sunkus Co., Ltd. that on August 9, 2016, they approved the organization of a new integrated company “FamilyMart UNY Holdings Co., Ltd.”. As a result, the Company has changed its corporate name to “FamilyMart UNY Holdings Co., Ltd.” The Depositary is also announcing a CUSIP change from “30706U107” to “30706W103”. The new corporate name and CUSIP of the Company will be effective for the ADSs as of the Effective Date. Please note that the American Depositary Receipts (“ADRs”) evidencing ADSs issued prior or subsequent to the date hereof, which do not reflect the new name and CUSIP notified hereby, do not need to be exchanged for new ADRs and may remain outstanding until such time as the holder(s) of such ADRs choose(s) to surrender them for any reason. If you have any questions regarding the above, please contact Citibank, N.A.