Transnational, Third World, and Global Feminisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: a Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 20 (2013-2014) Issue 1 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: 2013 Special Issue: Reproductive Article 2 Justice December 2013 Introduction: A Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications Joan C. Chrisler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Repository Citation Joan C. Chrisler, Introduction: A Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications, 20 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 1 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol20/iss1/2 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl INTRODUCTION: A GLOBAL APPROACH TO REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE—PSYCHOSOCIAL AND LEGAL ASPECTS AND IMPLICATIONS JOAN C. CHRISLER, PH.D.* INTRODUCTION I. TOPICS COVERED BY THE REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE MOVEMENT II. WHY REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IS DIFFICULT TO ACHIEVE III. WHY REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IS IMPORTANT IV. WHAT WE CAN DO IN THE STRUGGLE FOR REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE INTRODUCTION The term reproductive justice was introduced in the 1990s by a group of American Women of Color,1 who had attended the 1994 Inter- national Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), which was sponsored by the United Nations and is known as “the Cairo conference.” 2 After listening to debates by representatives of the gov- ernments of UN nation states about how to slow population growth and encourage the use of contraceptives and the extent to which women’s reproductive rights could/should be guaranteed, the group realized, as Loretta Ross later wrote, that “[o]ur ability to control what happens to our bodies is constantly challenged by poverty, racism, en- vironmental degradation, sexism, homophobia, and injustice . -

Intersectionality: T E Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community

#Intersectionality: T e Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community Intersectionality, is the marrow within the bones of fem- Tegan Zimmerman (PhD, Comparative Literature, inism. Without it, feminism will fracture even further – University of Alberta) is an Assistant Professor of En- Roxane Gay (2013) glish/Creative Writing and Women’s Studies at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. A recent Visiting Fel- This article analyzes the term “intersectional- low in the Centre for Contemporary Women’s Writing ity” as defined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw (1989, and the Institute of Modern Languages Research at the 1991) in relation to the digital turn and, in doing so, University of London, Zimmerman specializes in con- considers how this concept is being employed by fourth temporary women’s historical fiction and contempo- wave feminists on Twitter. Presently, little scholarship rary gender theory. Her book Matria Redux: Caribbean has been devoted to fourth wave feminism and its en- Women’s Historical Fiction, forthcoming from North- gagement with intersectionality; however, some notable western University Press, examines the concepts of ma- critics include Kira Cochrane, Michelle Goldberg, Mik- ternal history and maternal genealogy. ki Kendall, Ealasaid Munro, Lola Okolosie, and Roop- ika Risam.1 Intersectionality, with its consideration of Abstract class, race, age, ability, sexuality, and gender as inter- This article analyzes the term “intersectionality” as de- secting loci of discriminations or privileges, is now the fined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in relation to the overriding principle among today’s feminists, manifest digital turn: it argues that intersectionality is the dom- by theorizing tweets and hashtags on Twitter. Because inant framework being employed by fourth wave fem- fourth wave feminism, more so than previous feminist inists and that is most apparent on social media, espe- movements, focuses on and takes up online technolo- cially on Twitter. -

Her Money, My Sweat: Women Organizing to Transform Globalization

HER MONEY, MY SWEAT: WOMEN ORGANIZING TO TRANSFORM GLOBALIZATION Submitted to the School of Interdisciplinary Studies (Western College Program) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy Interdisciplinary Studies by Emily Bates Brown Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2007 APPROVED __________________________________________________ Yulonda E. Sano, Advisor ABSTRACT HER MONEY, MY SWEAT: WOMEN ORGANIZING TO TRANSFORM GLOBALIZATION Emily Bates Brown Women who live in Third World nations are disproportionately negatively affected by globalization. Moreover, theorizations of Third World women’s economic hardships are often characterized in terms of their victimization and helplessness even within Western feminist literature. Such characterizations have been intensely criticized in the last two decades by Third World and postcolonial feminist theorists who have effectively exposed the dangers of representing Third World women as a homogenized group. Western feminist discourse on gender, globalization, and Third World cultures has since made inroads toward addressing the specificity of identity issues such as race, class, and nationality, and in bridging the gap between the objectives of Western and non-Western women’s groups. Within discussions of the inequities of globalization and in efforts to organize women around globalization issues, negotiating similar identity issues and goals is a constant challenge. With an emphasis on the intersection of theory and practice, this thesis argues that for transnational feminist networks to organize constructively on globalization issues in the Third World, the agency and experience of local actors must be regarded as a primary source of legitimate knowledge. Only in this way will transnational feminist networks, which operate across both geographical and intangible borders, be successful in empowering local actors and in producing more viable, counter-hegemonic economic opportunities than currently exist under processes of globalization. -

Under Western Eyes Revisited: Feminist Solidarity Through

“Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles Author(s): Chandra Talpade Mohanty Reviewed work(s): Source: Signs, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Winter 2003), pp. 499-535 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/342914 . Accessed: 11/04/2012 00:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs. http://www.jstor.org Chandra Talpade Mohanty “Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles write this essay at the urging of a number of friends and with some trepidation, revisiting the themes and arguments of an essay written I some sixteen years ago. This is a difficult essay to write, and I undertake it hesitantly and with humility—yet feeling that I must do so to take fuller responsibility for my ideas, and perhaps to explain whatever influence they have had on debates in feminist theory. “Under Western Eyes” (1986) was not only my very first “feminist stud- ies” publication; it remains the one that marks my presence in the inter- national feminist community.1 I had barely completed my Ph.D. -

TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ITINERARIES NEXT WAVE NEW DIRECTIONS in WOMEN’S STUDIES a Series Edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman TRANSNATIONAL

TRANSNATIONAL Ashwini Tambe and Millie Thayer, editors FEMINIST Situating Theory and Activist Practice ITINERARIES TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ITINERARIES NEXT WAVE NEW DIRECTIONS IN WOMEN’S STUDIES A series edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman TRANSNATIONAL Situating Theory FEMINIST ITINERARIES and Activist Practice Edited by ashwini tambe and millie thayer DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS DURHAM AND LONDON 2021 © 2021 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Proj ect editor: Lisa Lawley Designed by Aimee C. Harrison Typeset in Minion Pro and ITC Franklin Gothic by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Tambe, Ashwini, editor. | Thayer, Millie, editor. Title: Transnational feminist itineraries : situating theory and ac tivist practice / Ashwini Tambe and Millie Thayer, eds. Other titles: Next wave (Duke University Press) Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2021. | Series: Next wave | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2020051607 (print) lccn 2020051608 (ebook) isbn 9781478013549 (hardcover) isbn 9781478014430 (paperback) isbn 9781478021735 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Feminist theory. | Transnationalism. | National- ism and feminism. | Intersectionality (Sociology) Classification: lcc hq1190 .t739 2021 (print) | lcc hq1190 (ebook) | ddc 305.42— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020051607 lc ebook rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020051608 -

Feminism and International Law in the Post- 9/11 Era

ARTICLE FEMINISM AND INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE POST- 9/11 ERA Jayne Huckerby* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 533 I. FEMINIST LEGAL CRITIQUES OF NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE POST-9/11 MOMENT .......................... 541 II. FEMINISM AND INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE LONG SHADOW OF 9/11 ................................................................. 547 A. The Role of Victimhood and Gendered Vulnerability ....... 547 B. Formalism and Inattentiveness to Gender-Based National Security Violations ............................................. 559 C. Which Women’s Rights Count and How: The Conjoining of Feminism and National Security ................ 569 D. Feminist Methods and Fractured Feminisms ...................... 584 CONCLUSION: FEMINISM, INTERNATIONAL LAW, AND NATIONAL SECURITY MOVING FORWARD ................. 588 INTRODUCTION Accounts of the role and influence of feminism in international law and global governance from the 1990s onward have tended to vacillate between analyses of the marginalization of feminist perspectives1 and the narrative of “governance feminism,”2 the idea * Associate Professor of Clinical Law, Duke University School of Law. I am very grateful for the comments of Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, Simon Thomas, and Katharine Young, and to Daria Anichkova, Eleni Bakst, and Yvonne Wang for outstanding research assistance. 1. See, e.g., Dianne Otto, Power and Danger: Feminist Engagement with International Law through the UN Security Council, 32 AUSTL. FEMINIST L.J. 97, 97–100, 118–21 (2010) [hereinafter Power and Danger] (noting that a common approach in many feminist analyses of international law and its institutions is to “tell a saga of ‘marginalisation’, ‘silencing’, and ‘talking to ourselves’”). 2. See Janet Halley et al., From the International to the Local in Feminist Legal Responses to Rape, Prostitution/Sex Work, and Sex Trafficking: Four Studies in Contemporary 533 534 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. -

Word and Image

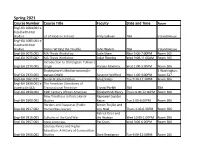

Word and Image Topics in Literary Theory II: Digital Engl-GA 2958.002 Literary Studies David Hoover Thurs 6:20-9:20PM TBA Gabriela Basterra & PUBHM-GA 1001 Theorizing Public Humanities Helga Tawil-Souri TBA TBA Michael Beckerman PUBHM-GA 1101 Practicing Public Humanities and Sophie Gonick TBA TBA Spring 2021 Course Descriptions Engl.GA 2270.001 Introduction to Old English: Tolkien's Origin Haruko Momma This course has two purposes: first, to introduce students to Old English language and literature and also to the culture and history in which this language was prospered; second, to use Old English as an entry point to explore J. R. R. Tolkien’s work, both academic and creative. This course will be divided into three parts. In the first part, we will go over basic Old English grammar and read, with the help of translations, passages from Old English prose including The Apollonius of Tyre, which Tolkien edited in 1958. Since Old English is noticeably different from its descendant Modern English, it needs to be approached almost as a foreign language: students will therefore be encouraged to memorize basic grammatical endings and core vocabulary (but not as intensely as Tolkien did). We will use Henry Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer and Anglo-Saxon Reader, two textbooks that Tolkien used to study Old English as a student, although there will be contemporary teaching materials to supplement them. In the second part, we will read shorter Old English poems while studying somewhat more advanced grammar, syntax, and versification. We will be reading Tolkien’s writing related to these poetic texts: for instance, we will read The Battle of Maldon, a poem about the English army’s defeat by the Viking invaders, side by side with Tolkien’s The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son, which is a fascinating dramatization of the poem; we will read some of the Advent Lyrics and discuss Tolkien’s use of one of the lyrics in The Lord of the Rings. -

Global Feminisms: Speaking & Acting About Women

I AM MALALA: A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS THEME 8: Global Feminisms: Speaking and Acting about Women and Girls For more information or to submit feedback about the resource guide, visit malala.gwu.edu. To expand the reach of Malala’s memoir—I am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban—and spread Malala’s message to young people and activists, the Global Women’s Institute (GWI) of the George Washington University (GW), in collaboration with the Malala Fund, developed a resource guide for high school and college students around the world. Building on the content of Malala’s memoir, the resource guide supports global efforts to mobilize women and men to address women’s and girls’ rights to an education. Malala’s memoir opens the door to some of the greatest challenges of our modern world. It is about politics, education, culture, religion and violence against women and girls. It is a moment in the life of a young girl and in the history of a country. To do these broad themes justice, faculty from a wide range of disciplines contributed to the development of the resource guide. The resource guide challenges students to think deeply, share their experiences, and engage with their communities. Each theme is divided into 4 parts: • Part 1 is the narrative with learning objectives to frame the conversation and help plan lessons; • Part 2 lists the resources to help students and teachers deepen their knowledge about the theme; • Part 3 lists individual and group activities, including some to be done outside of class if students are interested; • Part 4 is the high school supplement intended to help high school teachers introduce and discuss some of the concepts and context that appear in the theme narratives. -

Unthinking the Transnational

WGSS 494TI Integrative Experience Capstone: Professor Alex Deschamps Spring 2013 Unthinking the Transnational – Political Tue & Thu 2:30 – 3:45 pm Schedule#: 24813 Activism, Geographies of Development and Bartlett 274 Power Office: Bartlett 7B » Wednesdays 2:30 – 4:00 pm & by appointment Telephone: 545-1958 0r 57-0842 ▪ Email: [email protected] E-Reserves: wgss494ti▪ Course Description This course is about the framework of transnational women’s and gendered activisms and scholarship. We will survey the field of transnational feminist research and praxis, locating structures of power, practices of resistance, and the geographies of development at work in a range of theories and social movements. The course will not only examine the implementation of feminist politics and projects that have sought to ensure some measurable social, cultural, and economic changes, but also explore the ways conceptions of the ‘global’ and ‘transnational’ have informed these efforts. Students will have the opportunity to assess which of these practices can be applicable, transferable, and/or travel on a global scale. We will focus not only on the agency of individuals, but also on the impact on people’s lives and their communities as they adopt strategies to improve material, social, cultural, and political conditions of their lives. The relationship between academic theorizing and community organizing for productive social and political change is a vital, complex and ever-changing source of feminist inquiry. We will build on this relationship by interweaving activist social and political work with the theoretical interventions as well as feminist research methodology. We hope students will gain a fuller picture of the ways the framework of the “transnational” has informed and transformed theoretical, social and political spaces in both productive and problematic ways. -

1 Imagining Women's Lives: Feminism, Temporality, and the Metaphor Of

1 Imagining Women’s Lives: Feminism, Temporality, and the Metaphor of Waves The Pueblo people and the indigenous people of the Americas see time as round, not as a long linear string. If time is round, if time is an ocean, then something that happened 500 years ago may be quite immediate and real, whereas something inconsequential that happened an hour ago could be far away. Think of time as an ocean always moving . Leslie Marmon Silko, Interview Now begins to rise in me the familiar rhythm; words that have lain dormant now lift, now toss their crests, and fall and rise, and fall again. I am made and remade continually. Different people draw different words from me. Virginia Woolf, The Waves In spring 2013 the majority of the one hundred students in my undergraduate course on diversity in American culture responded to my question “What is feminism?” with positive and accurate definitions such as “feminism is the belief that women and men are of equal value and that they deserve equal rights and opportunities in society.” Most of the students were vaguely conservative; they were diverse in terms of race, nationality, gender, and academic fields; only a handful were majoring in the humanities; and yet, for the first time in my thirty years of teaching, the term “feminist” elicited almost no resistance or hostility. This surprising situation appears to represent a sea change from the typical experience that Toril Moi pinpointed in her 2006 essay, “‘I Am Not a Feminist, But . .’: How Feminism Became the F-Word.” Like many feminist faculty, Moi observed that since the mid-1990s, “most of my students no longer make feminism their central political and personal project” (1735). -

To Be a Black Woman, a Lesbian, and an Afro-Feminist in Cuba Today

To Be a Black Woman, a Lesbian, and an Afro-Feminist in Cuba Today Norma R. Guillard Limonta Estar juntas las mujeres no era suficiente, éramos distintas Estar juntas las mujeres gay no era suficiente, éramos distintas Estar juntas las mujeres negras no era suficiente, éramos distintas Estar juntas las mujeres lesbianas y negras no era suficiente, éramos distintas Cada una de nosotras teníamos sus propias necesidades y sus objetivos y alianzas muy diversas—Audre Lorde (cited by D’Atri, 2002, p. 1)1 Introduction Before talking about Afro-feminism in Cuba as a concept, there has to be an accounting of the history of struggle by women and the diverse processes through which global feminism underwent. The concept of feminism, whose significance does not only pertain to contemporary societies, has existed throughout centuries in different forms, although since industrialization it moved to a global scale. Cuba was not somehow disconnected from this process. Since the Middle Ages, philosophy and history has named different figures that, even if one did not call them such, were taking steps toward feminism. They were questioning male power like the women—e.g., Pitagóricas, Theano, Phintys, 1 [From the editor: The original reads (italics included) Being women together was not enough. We were different. Being gay-girls together was not enough. We were different. Being Black together was not enough. We were different. Being Black dykes together was not enough. We were different. (Lorde, 1984, p. 226) I left the Spanish translation of this for a very specific reason, of all the translations of the various author’s work, this is the only one that is not exactly a direct translation. -

A Transnational Feminist Perspective of US Health Coloniality

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2019 Dominating the Disease: A Transnational Feminist Perspective of U.S. Health Coloniality Jessica Ann Johnson University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Jessica Ann, "Dominating the Disease: A Transnational Feminist Perspective of U.S. Health Coloniality" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1586. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1586 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Dominating the Disease: A Transnational Feminist Perspective of U.S. Health Coloniality __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Jessica A. Johnson June 2019 Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Calafell, PhD ©Copyright by Jessica A. Johnson 2019 All Rights Reserved Author: Jessica A. Johnson Title: Dominating the Disease: A Transnational Feminist Perspective of U.S. Health Coloniality Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Calafell, PhD Degree Date: June 2019 Abstract HIV has been a pandemic since the 1980s with 70 million people infected since the beginning, about 35 million people have died of complications resulting from HIV, and an estimated 36.9 million people living with HIV in 2017 (WHO, “HIV and AIDS”).