Gender Equality?: a Transnational Feminist Analysis of the Un

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: a Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 20 (2013-2014) Issue 1 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: 2013 Special Issue: Reproductive Article 2 Justice December 2013 Introduction: A Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications Joan C. Chrisler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Repository Citation Joan C. Chrisler, Introduction: A Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications, 20 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 1 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol20/iss1/2 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl INTRODUCTION: A GLOBAL APPROACH TO REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE—PSYCHOSOCIAL AND LEGAL ASPECTS AND IMPLICATIONS JOAN C. CHRISLER, PH.D.* INTRODUCTION I. TOPICS COVERED BY THE REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE MOVEMENT II. WHY REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IS DIFFICULT TO ACHIEVE III. WHY REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IS IMPORTANT IV. WHAT WE CAN DO IN THE STRUGGLE FOR REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE INTRODUCTION The term reproductive justice was introduced in the 1990s by a group of American Women of Color,1 who had attended the 1994 Inter- national Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), which was sponsored by the United Nations and is known as “the Cairo conference.” 2 After listening to debates by representatives of the gov- ernments of UN nation states about how to slow population growth and encourage the use of contraceptives and the extent to which women’s reproductive rights could/should be guaranteed, the group realized, as Loretta Ross later wrote, that “[o]ur ability to control what happens to our bodies is constantly challenged by poverty, racism, en- vironmental degradation, sexism, homophobia, and injustice . -

Transnational, Third World, and Global Feminisms

1 Transnational, Third World, and Global Feminisms Ranjoo S. Herr Encyclopedia of Race and Racism (second ed.). Routledge, 2013 Check with the original to verify italics Third world, transnational, and global feminisms focus on the situation of racial-ethnic women originating from the third world (or the South), whether or not they reside in the first world (or the North or West). This entry refers to these women as ―third world women.‖ Most second- wave white feminisms in the West—liberal, radical, psychoanalytic, or ―care-focused‖ feminisms (Tong 2009)—have assumed that women everywhere face similar oppression merely by virtue of their sex/gender. Global feminism as it first emerged in the 1980s was largely a global application of this white feminist outlook. Third world and transnational feminisms emerged in the 1980s and early 1990s to challenge this white feminist assumption. These feminisms are predicated on the premise that women‘s oppression diverges globally due to not only gender, but also race, class, ethnicity, religion, and nation. Therefore, third world women suffer from multiple forms of oppression qualitatively different from the gender oppression experienced by middle-class white women in the West. Third world and transnational feminisms are distinct, however, not only in their origins and outlooks, but also in their goals and priorities. This entry begins by examining the genealogies of these feminisms, in the process of which their differences will be identified. It then explains four main characteristics that these feminisms share. After reviewing some instances of third world, transnational, and global feminist activities, the entry concludes by suggesting a way to resolve a potential conflict between the local and the universal facing third world, transnational, and global feminists. -

Implementing Armenian Feminist Literature Within Feminist Discourse

YOU HAVE A VOICE HERE: IMPLEMENTING ARMENIAN FEMINIST LITERATURE WITHIN FEMINIST DISCOURSE By Grace Hart A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: Applied English Studies Committee Membership Dr. Christina Accomando, Committee Chair Dr. Lisa Tremain, Committee Member Dr. Janet Winston, Program Graduate Coordinator July 2020 “Writing is dangerous because we are afraid of what the writing reveals, the fears, the angers, the strengths of a woman under a triple or quadruple oppression. Yet in that very act lies our survival because a woman who writes has power. And a woman with power is feared.” - Gloria Anzaldúa ABSTRACT YOU HAVE A VOICE HERE: IMPLEMENTING ARMENIAN FEMINIST LITERATURE WITHIN FEMINIST DISCOURSE Grace Hart This project melds personal narrative with literary criticism, as it excavates the literature of Armenian writer and political activist Zabel Yessayan, particularly with her novel My Soul in Exile and memoir The Gardens of Silihdar. I argue that the voice of Zabel Yessayan should be included in the feminist women of color discourse within institutions in the United States. I develop this argument by bringing in the works of Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa’s anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color and showing parallels in themes and lenses such as excavating traumatic histories, the importance of personal identity, and using writing as a form of resistance. Zabel Yessayan’s texts and This Bridge both comprise stories conveying the theme of residing in the “in-between,” and topics concerning womanhood, culture, identity, alienation and isolation. -

Feminism Approach in Novel Salah Pilih by Nur St

FEMINISM APPROACH IN NOVEL SALAH PILIH BY NUR ST. ISKANDAR Fitriani Lubis Medan State University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Feminism began to develop in society, especially women who have higher education. Even so there are also some people who do not understand the understanding of feminism. Feminism is born from the unfair treatment felt by women. Through literary work, feminism was born as a thought to change the unfavorable situation for women. This paper examines the approach of feminism in the novel Salah Pilih by Nur St. Iskandar. Keywords: Literary Criticism, Feminism, Novel Feminism is a movement that demands the emancipation or equality and justice of rights by men. Feminism comes from Latin, femina or female. This term began to be used in the 1890s, referring to the theory of equality of men and women and the movement to obtain women's rights. The widespread definition of feminism is the advocacy of equality of women's rights in political, social, and economic matters. The feminist movement began in the late 18th century and flourished throughout the twentieth century beginning with the equality of women's political rights. Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is considered one of the earliest feminist writings containing criticisms of the French Revolution which applies only to men but not to women. A century later in Indonesia, Raden Ajeng Kartini co-authored his thoughts on the criticism of the situation of Javanese women who were not given the opportunity to attain equal education with men other than criticism of Dutch colonialism. -

Intersectionality: T E Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community

#Intersectionality: T e Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community Intersectionality, is the marrow within the bones of fem- Tegan Zimmerman (PhD, Comparative Literature, inism. Without it, feminism will fracture even further – University of Alberta) is an Assistant Professor of En- Roxane Gay (2013) glish/Creative Writing and Women’s Studies at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. A recent Visiting Fel- This article analyzes the term “intersectional- low in the Centre for Contemporary Women’s Writing ity” as defined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw (1989, and the Institute of Modern Languages Research at the 1991) in relation to the digital turn and, in doing so, University of London, Zimmerman specializes in con- considers how this concept is being employed by fourth temporary women’s historical fiction and contempo- wave feminists on Twitter. Presently, little scholarship rary gender theory. Her book Matria Redux: Caribbean has been devoted to fourth wave feminism and its en- Women’s Historical Fiction, forthcoming from North- gagement with intersectionality; however, some notable western University Press, examines the concepts of ma- critics include Kira Cochrane, Michelle Goldberg, Mik- ternal history and maternal genealogy. ki Kendall, Ealasaid Munro, Lola Okolosie, and Roop- ika Risam.1 Intersectionality, with its consideration of Abstract class, race, age, ability, sexuality, and gender as inter- This article analyzes the term “intersectionality” as de- secting loci of discriminations or privileges, is now the fined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in relation to the overriding principle among today’s feminists, manifest digital turn: it argues that intersectionality is the dom- by theorizing tweets and hashtags on Twitter. Because inant framework being employed by fourth wave fem- fourth wave feminism, more so than previous feminist inists and that is most apparent on social media, espe- movements, focuses on and takes up online technolo- cially on Twitter. -

Her Money, My Sweat: Women Organizing to Transform Globalization

HER MONEY, MY SWEAT: WOMEN ORGANIZING TO TRANSFORM GLOBALIZATION Submitted to the School of Interdisciplinary Studies (Western College Program) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy Interdisciplinary Studies by Emily Bates Brown Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2007 APPROVED __________________________________________________ Yulonda E. Sano, Advisor ABSTRACT HER MONEY, MY SWEAT: WOMEN ORGANIZING TO TRANSFORM GLOBALIZATION Emily Bates Brown Women who live in Third World nations are disproportionately negatively affected by globalization. Moreover, theorizations of Third World women’s economic hardships are often characterized in terms of their victimization and helplessness even within Western feminist literature. Such characterizations have been intensely criticized in the last two decades by Third World and postcolonial feminist theorists who have effectively exposed the dangers of representing Third World women as a homogenized group. Western feminist discourse on gender, globalization, and Third World cultures has since made inroads toward addressing the specificity of identity issues such as race, class, and nationality, and in bridging the gap between the objectives of Western and non-Western women’s groups. Within discussions of the inequities of globalization and in efforts to organize women around globalization issues, negotiating similar identity issues and goals is a constant challenge. With an emphasis on the intersection of theory and practice, this thesis argues that for transnational feminist networks to organize constructively on globalization issues in the Third World, the agency and experience of local actors must be regarded as a primary source of legitimate knowledge. Only in this way will transnational feminist networks, which operate across both geographical and intangible borders, be successful in empowering local actors and in producing more viable, counter-hegemonic economic opportunities than currently exist under processes of globalization. -

Under Western Eyes Revisited: Feminist Solidarity Through

“Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles Author(s): Chandra Talpade Mohanty Reviewed work(s): Source: Signs, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Winter 2003), pp. 499-535 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/342914 . Accessed: 11/04/2012 00:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs. http://www.jstor.org Chandra Talpade Mohanty “Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles write this essay at the urging of a number of friends and with some trepidation, revisiting the themes and arguments of an essay written I some sixteen years ago. This is a difficult essay to write, and I undertake it hesitantly and with humility—yet feeling that I must do so to take fuller responsibility for my ideas, and perhaps to explain whatever influence they have had on debates in feminist theory. “Under Western Eyes” (1986) was not only my very first “feminist stud- ies” publication; it remains the one that marks my presence in the inter- national feminist community.1 I had barely completed my Ph.D. -

TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ITINERARIES NEXT WAVE NEW DIRECTIONS in WOMEN’S STUDIES a Series Edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman TRANSNATIONAL

TRANSNATIONAL Ashwini Tambe and Millie Thayer, editors FEMINIST Situating Theory and Activist Practice ITINERARIES TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ITINERARIES NEXT WAVE NEW DIRECTIONS IN WOMEN’S STUDIES A series edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman TRANSNATIONAL Situating Theory FEMINIST ITINERARIES and Activist Practice Edited by ashwini tambe and millie thayer DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS DURHAM AND LONDON 2021 © 2021 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Proj ect editor: Lisa Lawley Designed by Aimee C. Harrison Typeset in Minion Pro and ITC Franklin Gothic by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Tambe, Ashwini, editor. | Thayer, Millie, editor. Title: Transnational feminist itineraries : situating theory and ac tivist practice / Ashwini Tambe and Millie Thayer, eds. Other titles: Next wave (Duke University Press) Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2021. | Series: Next wave | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2020051607 (print) lccn 2020051608 (ebook) isbn 9781478013549 (hardcover) isbn 9781478014430 (paperback) isbn 9781478021735 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Feminist theory. | Transnationalism. | National- ism and feminism. | Intersectionality (Sociology) Classification: lcc hq1190 .t739 2021 (print) | lcc hq1190 (ebook) | ddc 305.42— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020051607 lc ebook rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020051608 -

Feminism and International Law in the Post- 9/11 Era

ARTICLE FEMINISM AND INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE POST- 9/11 ERA Jayne Huckerby* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 533 I. FEMINIST LEGAL CRITIQUES OF NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE POST-9/11 MOMENT .......................... 541 II. FEMINISM AND INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE LONG SHADOW OF 9/11 ................................................................. 547 A. The Role of Victimhood and Gendered Vulnerability ....... 547 B. Formalism and Inattentiveness to Gender-Based National Security Violations ............................................. 559 C. Which Women’s Rights Count and How: The Conjoining of Feminism and National Security ................ 569 D. Feminist Methods and Fractured Feminisms ...................... 584 CONCLUSION: FEMINISM, INTERNATIONAL LAW, AND NATIONAL SECURITY MOVING FORWARD ................. 588 INTRODUCTION Accounts of the role and influence of feminism in international law and global governance from the 1990s onward have tended to vacillate between analyses of the marginalization of feminist perspectives1 and the narrative of “governance feminism,”2 the idea * Associate Professor of Clinical Law, Duke University School of Law. I am very grateful for the comments of Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, Simon Thomas, and Katharine Young, and to Daria Anichkova, Eleni Bakst, and Yvonne Wang for outstanding research assistance. 1. See, e.g., Dianne Otto, Power and Danger: Feminist Engagement with International Law through the UN Security Council, 32 AUSTL. FEMINIST L.J. 97, 97–100, 118–21 (2010) [hereinafter Power and Danger] (noting that a common approach in many feminist analyses of international law and its institutions is to “tell a saga of ‘marginalisation’, ‘silencing’, and ‘talking to ourselves’”). 2. See Janet Halley et al., From the International to the Local in Feminist Legal Responses to Rape, Prostitution/Sex Work, and Sex Trafficking: Four Studies in Contemporary 533 534 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. -

Quiet Rumours: an Anarcha-Feminist Reader Ebook, Epub

QUIET RUMOURS: AN ANARCHA-FEMINIST READER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Emma Goldman,Voltairine De Cleyre,Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz,Jo Freeman | 136 pages | 11 Dec 2012 | AK Press | 9781849351034 | English | Edinburgh, United Kingdom Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader PDF Book Refresh and try again. Emma Goldman's "A Woman Without a Country," though a great text, mentioned nothing of feminism, let alone anarchist feminism. View all 9 comments. Quiet Rumors provides anarcha-feminists and other readers with a solid archive of political inquiry stretching across two centuries and engaging the debates, disappointments, and dreams expressed within critical moments in multiple liberation movements. Nor is a fringe mention of intersectionality enough to make our feminism intersectional. Why were they picked for this anthology? Most these essays didn't have any context introducing them: what year were they written? Aug 04, Ariel rated it really liked it Recommended to Ariel by: Lambert. Known as a rebel, a labor agitator, an ardent proponent of birth control and free speech, a feminist, a lecturer and a writer, Goldman is the author of countless essays, as well as several collections of writings published posthumously, and her 2-volume autobiography, Living My Life. Some of the classical stuff was kinda boring. The articles from the s, which ought to be the most interesting since they are from new left feminists dis This is mainly of historical interest, and in the meantime probably all of the documents collected here are freely available online. Technopranks: Carving out a message in electronic space. A: Its policy, it aims, its principles. -

FEMINIST LITERARY THEORY a Reader

FEMINIST LITERARY THEORY A Reader Second Edition Edited by Mary Eagleton P u b I i s h e r s Contents Preface xi Acknowledgements xv 1 Finding a Female Tradition Introduction 1 Extracts from: A Room of One's Own VIRGINIA WOOLF 9 Literary Women ELLEN MOERS 10 A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Bronte to Lessing ELAINE SHOW ALTER 14 'What Has Never Been: An Overview of Lesbian Feminist Literary Criticism' BONNIE ZIMMERMAN 18 'Compulsory Heterosexuality andXesbian Existence' ADRIENNE RICH 24 'Saving the Life That Is Your Own: The Importance of Models in the Artist's Life ALICE WALKER 30 Title Essay In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens ALICE WALKER 33 Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory CHRIS WEEDON 36 'Race and Gender in the Shaping of the American Literary Canon: A Case Study from the Twenties' PAUL LAUTER 39 Women's Oppression Today: Problems in Marxist Feminist Analysis MICHELE BARRETT 45 'Writing "Race" and the Difference it Makes' HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR 46 'Parables and Politics: Feminist Criticism in 1986' NANCY K. MILLER 48 Reading Woman: Essays in Feminist Criticism MARY JACOBUS 51 'Happy Families? Feminist Reproduction and Matrilineal Thought' LINDA R. WILLIAMS 52 'What Women's Eyes See' VIVIANE FORRESTER 56 'Women and Madness: The Critical Phallacy' SHOSHANA FELMAN 58 vi CONTENTS 'French Feminism in an International Frame' GAYATRI CHAKRAVORTY SPIVAK 59 Feminist Literary History: A Defence JANET TODD 62 2 Women and Literary Production Introduction 66 Extracts from: A Room of One's Own VIRGINIA WOOLF 73 'Professions for, Women' VIRGINIA WOOLF 78 Silences TILLIE OLSEN 80 'When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision' ADRIENNE RICH 84 The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination SANDRA M. -

Word and Image

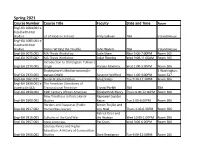

Word and Image Topics in Literary Theory II: Digital Engl-GA 2958.002 Literary Studies David Hoover Thurs 6:20-9:20PM TBA Gabriela Basterra & PUBHM-GA 1001 Theorizing Public Humanities Helga Tawil-Souri TBA TBA Michael Beckerman PUBHM-GA 1101 Practicing Public Humanities and Sophie Gonick TBA TBA Spring 2021 Course Descriptions Engl.GA 2270.001 Introduction to Old English: Tolkien's Origin Haruko Momma This course has two purposes: first, to introduce students to Old English language and literature and also to the culture and history in which this language was prospered; second, to use Old English as an entry point to explore J. R. R. Tolkien’s work, both academic and creative. This course will be divided into three parts. In the first part, we will go over basic Old English grammar and read, with the help of translations, passages from Old English prose including The Apollonius of Tyre, which Tolkien edited in 1958. Since Old English is noticeably different from its descendant Modern English, it needs to be approached almost as a foreign language: students will therefore be encouraged to memorize basic grammatical endings and core vocabulary (but not as intensely as Tolkien did). We will use Henry Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer and Anglo-Saxon Reader, two textbooks that Tolkien used to study Old English as a student, although there will be contemporary teaching materials to supplement them. In the second part, we will read shorter Old English poems while studying somewhat more advanced grammar, syntax, and versification. We will be reading Tolkien’s writing related to these poetic texts: for instance, we will read The Battle of Maldon, a poem about the English army’s defeat by the Viking invaders, side by side with Tolkien’s The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son, which is a fascinating dramatization of the poem; we will read some of the Advent Lyrics and discuss Tolkien’s use of one of the lyrics in The Lord of the Rings.