A Transnational Feminist Perspective of US Health Coloniality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: a Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 20 (2013-2014) Issue 1 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: 2013 Special Issue: Reproductive Article 2 Justice December 2013 Introduction: A Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications Joan C. Chrisler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Repository Citation Joan C. Chrisler, Introduction: A Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications, 20 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 1 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol20/iss1/2 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl INTRODUCTION: A GLOBAL APPROACH TO REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE—PSYCHOSOCIAL AND LEGAL ASPECTS AND IMPLICATIONS JOAN C. CHRISLER, PH.D.* INTRODUCTION I. TOPICS COVERED BY THE REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE MOVEMENT II. WHY REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IS DIFFICULT TO ACHIEVE III. WHY REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IS IMPORTANT IV. WHAT WE CAN DO IN THE STRUGGLE FOR REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE INTRODUCTION The term reproductive justice was introduced in the 1990s by a group of American Women of Color,1 who had attended the 1994 Inter- national Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), which was sponsored by the United Nations and is known as “the Cairo conference.” 2 After listening to debates by representatives of the gov- ernments of UN nation states about how to slow population growth and encourage the use of contraceptives and the extent to which women’s reproductive rights could/should be guaranteed, the group realized, as Loretta Ross later wrote, that “[o]ur ability to control what happens to our bodies is constantly challenged by poverty, racism, en- vironmental degradation, sexism, homophobia, and injustice . -

Transnational, Third World, and Global Feminisms

1 Transnational, Third World, and Global Feminisms Ranjoo S. Herr Encyclopedia of Race and Racism (second ed.). Routledge, 2013 Check with the original to verify italics Third world, transnational, and global feminisms focus on the situation of racial-ethnic women originating from the third world (or the South), whether or not they reside in the first world (or the North or West). This entry refers to these women as ―third world women.‖ Most second- wave white feminisms in the West—liberal, radical, psychoanalytic, or ―care-focused‖ feminisms (Tong 2009)—have assumed that women everywhere face similar oppression merely by virtue of their sex/gender. Global feminism as it first emerged in the 1980s was largely a global application of this white feminist outlook. Third world and transnational feminisms emerged in the 1980s and early 1990s to challenge this white feminist assumption. These feminisms are predicated on the premise that women‘s oppression diverges globally due to not only gender, but also race, class, ethnicity, religion, and nation. Therefore, third world women suffer from multiple forms of oppression qualitatively different from the gender oppression experienced by middle-class white women in the West. Third world and transnational feminisms are distinct, however, not only in their origins and outlooks, but also in their goals and priorities. This entry begins by examining the genealogies of these feminisms, in the process of which their differences will be identified. It then explains four main characteristics that these feminisms share. After reviewing some instances of third world, transnational, and global feminist activities, the entry concludes by suggesting a way to resolve a potential conflict between the local and the universal facing third world, transnational, and global feminists. -

Lai CV April 24 2018 Ucalg For

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Curriculum Vitae Date: April 2018 1. SURNAME: Lai FIRST NAME: Larissa MIDDLE NAME(S): -- 2. DEPARTMENT/SCHOOL: English 3. FACULTY: Arts 4. PRESENT RANK: Associate Professor/ CRC II SINCE: 2014 5. POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION University or Institution Degree Subject Area Dates University of Calgary PhD English 2001 - 2006 University of East Anglia MA Creative Writing 2000 - 2001 University of British Columbia BA (Hon.) Sociology 1985 - 1990 Title of Dissertation and Name of Supervisor Dissertation: The “I” of the Storm: Practice, Subjectivity and Time Zones in Asian Canadian Writing Supervisor: Dr. Aruna Srivastava 6. EMPLOYMENT RECORD (a) University, Company or Organization Rank or Title Dates University of Calgary, Department of English Associate Professor/ CRC 2014-present II in Creative Writing University of British Columbia, Department of English Associate Professor 2014-2016 (on leave) University of British Columbia, Department of English Assistant Professor 2007-2014 University of British Columbia, Department of English SSHRC Postdoctoral 2006-2007 Fellow Simon Fraser University, Department of English Writer-in-Residence 2006 University of Calgary, Department of English Instructor 2005 University of Calgary, Department of Communications Instructor 2004 Clarion West, Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop Instructor 2004 University of Calgary, Department of Communications Teaching Assistant 2002-2004 University of Calgary, Department of English Teaching Assistant 2001-2002 Writers for Change, Asian Canadian Writers’ -

TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ITINERARIES NEXT WAVE NEW DIRECTIONS in WOMEN’S STUDIES a Series Edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman TRANSNATIONAL

TRANSNATIONAL Ashwini Tambe and Millie Thayer, editors FEMINIST Situating Theory and Activist Practice ITINERARIES TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ITINERARIES NEXT WAVE NEW DIRECTIONS IN WOMEN’S STUDIES A series edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman TRANSNATIONAL Situating Theory FEMINIST ITINERARIES and Activist Practice Edited by ashwini tambe and millie thayer DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS DURHAM AND LONDON 2021 © 2021 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Proj ect editor: Lisa Lawley Designed by Aimee C. Harrison Typeset in Minion Pro and ITC Franklin Gothic by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Tambe, Ashwini, editor. | Thayer, Millie, editor. Title: Transnational feminist itineraries : situating theory and ac tivist practice / Ashwini Tambe and Millie Thayer, eds. Other titles: Next wave (Duke University Press) Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2021. | Series: Next wave | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2020051607 (print) lccn 2020051608 (ebook) isbn 9781478013549 (hardcover) isbn 9781478014430 (paperback) isbn 9781478021735 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Feminist theory. | Transnationalism. | National- ism and feminism. | Intersectionality (Sociology) Classification: lcc hq1190 .t739 2021 (print) | lcc hq1190 (ebook) | ddc 305.42— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020051607 lc ebook rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020051608 -

Stories in Selected 20Th-Century Texts by Québécois Women Writers Jessica Mcbride University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 12-1-2017 Alternative Biographies: (Re)telling Feminine (Hi)stories in Selected 20th-Century Texts by Québécois Women Writers Jessica McBride University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation McBride, Jessica, "Alternative Biographies: (Re)telling Feminine (Hi)stories in Selected 20th-Century Texts by Québécois Women Writers" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1655. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1655 Alternative Biographies: (Re)telling Feminine (Hi)stories in Selected 20th-Century Texts by Québécois Women Writers Jessica A. McBride, PhD University of Connecticut, 2017 The objective of this dissertation is to examine the tendency on the part of several québécois women authors from the 20th century to create alternative feminine biographies for forgotten, undervalued, or misrepresented women from the past. Given the complex relationship the Québécois have with their provincial history, and the central role chauvinistic representations of women and the “Québec national text” play in safeguarding the québécois cultural identity, contemporary women writers from Québec are singularly poised to resurrect, recreate, revive, and rewrite the feminine historical experience into the traditional discourse of History. From Québec’s most famous woman writer, Anne Hébert, to a lesser known militant lesbian playwright, Jovette Marchessault, and other québécois women writers along the spectrum, there exists a common trope: plays and novels in which homo- or heterodiegetic women narrators feel compelled to (re)tell another woman’s feminine (hi)story. Some examples of this practice appear initially to be somewhat traditional works of historical fiction, others ignore almost entirely the referential world beyond the confines of their pages. -

New Books on Women & Feminism

NEW BOOKS ON WOMEN & FEMINISM No. 50, Spring 2007 CONTENTS Scope Statement .................. 1 Politics/ Political Theory . 31 Anthropology...................... 1 Psychology ...................... 32 Art/ Architecture/ Photography . 2 Reference/ Bibliography . 33 Biography ........................ 3 Religion/ Spirituality . 34 Economics/ Business/ Work . 6 Science/ Mathematics/ Technology . 37 Education ........................ 8 Sexuality ........................ 37 Film/ Theater...................... 9 Sociology/ Social Issues . 38 Health/ Medicine/ Biology . 10 Sports & Recreation . 44 History.......................... 12 Women’s Movement/ General Women's Studies . 44 Humor.......................... 18 Periodicals ...................... 46 Language/ Linguistics . 18 Index: Authors, Editors, & Translators . 47 Law ............................ 19 Index: Subjects ................... 58 Lesbian Studies .................. 20 Citation Abbreviations . 75 Literature: Drama ................. 20 Literature: Fiction . 21 New Books on Women & Feminism is published by Phyllis Hol- man Weisbard, Women's Studies Librarian for the University of Literature: History & Criticism . 22 Wisconsin System, 430 Memorial Library, 728 State Street, Madi- son, WI 53706. Phone: (608) 263-5754. Email: wiswsl @library.wisc.edu. Editor: Linda Fain. Compilers: Amy Dachen- Literature: Mixed Genres . 25 bach, Nicole Grapentine-Benton, Christine Kuenzle, JoAnne Leh- man, Heather Shimon, Phyllis Holman Weisbard. Graphics: Dan- iel Joe. ISSN 0742-7123. Annual subscriptions are $8.25 for indi- Literature: Poetry . 26 viduals and $15.00 for organizations affiliated with the UW Sys- tem; $16.00 for non-UW individuals and non-profit women's pro- grams in Wisconsin ($30.00 outside the state); and $22.50 for Media .......................... 28 libraries and other organizations in Wisconsin ($55.00 outside the state). Outside the U.S., add $13.00 for surface mail to Canada, Music/ Dance .................... 29 $15.00 elsewhere; or $25.00 for air mail to Canada, $55.00 else- where. -

Izabella Penier Culture-Bearing Women

Izabella Penier Culture-bearing Women: The Black Women Renaissance and Cultural Nationalism This monograph was written during Marie Curie-Sklodowska Fellowship 2016-2018 (European Union’s Horizon 2020 grant agreement No 706741) Izabella Penier Culture-bearing Women The Black Women Renaissance and Cultural Nationalism Managing Editor: Katarzyna Grzegorek Language Editor: Adam Leverton ISBN 978-83-956095-4-1 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-83-956095-5-8 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-83-956095-6-5 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go 4o http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. © 2019 Izabella Penier Published by De Gruyter Poland Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Grzegorek Language Editor: Adam Leverton www.degruyter.com Cover illustration: https://unsplash.com/@jeka_fe by Jessica Felicio Contents Preface 1 1 Introduction: The Black Women Renaissance, Matrilineal Romances and the “Volkish Tradition” 16 1.1 African Americans as an “Imagined” Community and the Roots of the “Volkish” Tradition 32 1.2 Two Versions of the National “Family Plot”: Black National Theatre and the Historical /Heritage Writing of the Black Women’s Renaissance 40 1.3 The Black Women’s Renaissance and Black Cultural Nationalism: Can Nationalism and Feminism Merge? -

Word and Image

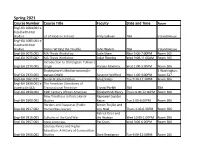

Word and Image Topics in Literary Theory II: Digital Engl-GA 2958.002 Literary Studies David Hoover Thurs 6:20-9:20PM TBA Gabriela Basterra & PUBHM-GA 1001 Theorizing Public Humanities Helga Tawil-Souri TBA TBA Michael Beckerman PUBHM-GA 1101 Practicing Public Humanities and Sophie Gonick TBA TBA Spring 2021 Course Descriptions Engl.GA 2270.001 Introduction to Old English: Tolkien's Origin Haruko Momma This course has two purposes: first, to introduce students to Old English language and literature and also to the culture and history in which this language was prospered; second, to use Old English as an entry point to explore J. R. R. Tolkien’s work, both academic and creative. This course will be divided into three parts. In the first part, we will go over basic Old English grammar and read, with the help of translations, passages from Old English prose including The Apollonius of Tyre, which Tolkien edited in 1958. Since Old English is noticeably different from its descendant Modern English, it needs to be approached almost as a foreign language: students will therefore be encouraged to memorize basic grammatical endings and core vocabulary (but not as intensely as Tolkien did). We will use Henry Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer and Anglo-Saxon Reader, two textbooks that Tolkien used to study Old English as a student, although there will be contemporary teaching materials to supplement them. In the second part, we will read shorter Old English poems while studying somewhat more advanced grammar, syntax, and versification. We will be reading Tolkien’s writing related to these poetic texts: for instance, we will read The Battle of Maldon, a poem about the English army’s defeat by the Viking invaders, side by side with Tolkien’s The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son, which is a fascinating dramatization of the poem; we will read some of the Advent Lyrics and discuss Tolkien’s use of one of the lyrics in The Lord of the Rings. -

Unthinking the Transnational

WGSS 494TI Integrative Experience Capstone: Professor Alex Deschamps Spring 2013 Unthinking the Transnational – Political Tue & Thu 2:30 – 3:45 pm Schedule#: 24813 Activism, Geographies of Development and Bartlett 274 Power Office: Bartlett 7B » Wednesdays 2:30 – 4:00 pm & by appointment Telephone: 545-1958 0r 57-0842 ▪ Email: [email protected] E-Reserves: wgss494ti▪ Course Description This course is about the framework of transnational women’s and gendered activisms and scholarship. We will survey the field of transnational feminist research and praxis, locating structures of power, practices of resistance, and the geographies of development at work in a range of theories and social movements. The course will not only examine the implementation of feminist politics and projects that have sought to ensure some measurable social, cultural, and economic changes, but also explore the ways conceptions of the ‘global’ and ‘transnational’ have informed these efforts. Students will have the opportunity to assess which of these practices can be applicable, transferable, and/or travel on a global scale. We will focus not only on the agency of individuals, but also on the impact on people’s lives and their communities as they adopt strategies to improve material, social, cultural, and political conditions of their lives. The relationship between academic theorizing and community organizing for productive social and political change is a vital, complex and ever-changing source of feminist inquiry. We will build on this relationship by interweaving activist social and political work with the theoretical interventions as well as feminist research methodology. We hope students will gain a fuller picture of the ways the framework of the “transnational” has informed and transformed theoretical, social and political spaces in both productive and problematic ways. -

Introducing Women's and Gender Studies: a Collection of Teaching

Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 1 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Collection of Teaching Resources Edited by Elizabeth M. Curtis Fall 2007 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 2 Copyright National Women's Studies Association 2007 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 3 Table of Contents Introduction……………………..………………………………………………………..6 Lessons for Pre-K-12 Students……………………………...…………………….9 “I am the Hero of My Life Story” Art Project Kesa Kivel………………………………………………………….……..10 Undergraduate Introductory Women’s and Gender Studies Courses…….…15 Lecture Courses Introduction to Women’s Studies Jennifer Cognard-Black………………………………………………………….……..16 Introduction to Women’s Studies Maria Bevacqua……………………………………………………………………………23 Introduction to Women’s Studies Vivian May……………………………………………………………………………………34 Introduction to Women’s Studies Jeanette E. Riley……………………………………………………………………………...47 Perspectives on Women’s Studies Ann Burnett……………………………………………………………………………..55 Seminar Courses Introduction to Women’s Studies Lynda McBride………………………..62 Introduction to Women’s Studies Jocelyn Stitt…………………………….75 Introduction to Women’s Studies Srimati Basu……………………………………………………………...…………………86 Introduction to Women’s Studies Susanne Beechey……………………………………...…………………………………..92 Introduction to Women’s Studies Risa C. Whitson……………………105 Women: Images and Ideas Angela J. LaGrotteria…………………………………………………………………………118 The Dynamics of Race, Sex, and Class Rama Lohani Chase…………………………………………………………………………128 -

World Economic Forum on Africa

World Economic Forum on Africa List of Participants As of 7 April 2014 Cape Town, South Africa, 8-10 May 2013 Jon Aarons Senior Managing Director FTI Consulting United Kingdom Muhammad Programme Manager Center for Democracy and Egypt Abdelrehem Social Peace Studies Khalid Abdulla Chief Executive Officer Sekunjalo Investments Ltd South Africa Asanga Executive Director Lakshman Kadirgamar Sri Lanka Abeyagoonasekera Institute for International Relations and Strategic Studies Mahmoud Aboud Capacity Development Coordinator, Frontline Maternal and Child Health Empowerment Project, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Sudan Fatima Haram Acyl Commissioner for Trade and Industry, African Union, Addis Ababa Jean-Paul Adam Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Seychelles Tawia Esi Director, Ghana Legal Affairs Newmont Ghana Gold Ltd Ghana Addo-Ashong Adekeye Adebajo Executive Director The Centre for Conflict South Africa Resolution Akinwumi Ayodeji Minister of Agriculture and Rural Adesina Development of Nigeria Tosin Adewuyi Managing Director and Senior Country JPMorgan Nigeria Officer, Nigeria Olufemi Adeyemo Group Chief Financial Officer Oando Plc Nigeria Olusegun Aganga Minister of Industry, Trade and Investment of Nigeria Vikram Agarwal Vice-President, Procurement Unilever Singapore Anant Agarwal President edX USA Pascal K. Agboyibor Managing Partner Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe France Aigboje Managing Director Access Bank Plc Nigeria Aig-Imoukhuede Wadia Ait Hamza Manager, Public Affairs Rabat School of Governance Morocco & Economics -

51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA

Northeast Modern Language Association 51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA Local Host: Boston University Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo SUNY 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Carole Salmon | University of Massachusetts Lowell First Vice President Brandi So | Department of Online Learning, Touro College and University System Second Vice President Bernadette Wegenstein | Johns Hopkins University Past President Simona Wright | The College of New Jersey American and Anglophone Studies Director Benjamin Railton | Fitchburg State University British and Anglophone Studies Director Elaine Savory | The New School Comparative Literature Director Katherine Sugg | Central Connecticut State University Creative Writing, Publishing, and Editing Director Abby Bardi | Prince George’s Community College Cultural Studies and Media Studies Director Maria Matz | University of Massachusetts Lowell French and Francophone Studies Director Olivier Le Blond | University of North Georgia German Studies Director Alexander Pichugin | Rutgers, State University of New Jersey Italian Studies Director Emanuela Pecchioli | University at Buffalo, SUNY Pedagogy and Professionalism Director Maria Plochocki | City University of New York Spanish and Portuguese Studies Director Victoria L. Ketz | La Salle University CAITY Caucus President and Representative Francisco Delgado | Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY Diversity Caucus Representative Susmita Roye | Delaware State University Graduate Student Caucus Representative Christian Ylagan | University