Diversity and Sustainability at Work. Policies and Practices from Culture and Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HERITAGE for PLANET EARTH® 2017 One Planet, One Origin, Many Cultures, One Shared Destiny, Or None!

19th General Assembly and International Conference of the Fondazione Romualdo Del Bianco Life Beyond Tourism Travel for Dialogue ® HERITAGE for PLANET EARTH 2017 One Planet, One Origin, Many Cultures, One Shared Destiny, Or None! “Smart Travel, Smart Architecture, Heritage and its Enjoyment for Dialogue” Florence, March 11-13, 2017 Auditorium al Duomo, via de’ Cerretani 54/r - Firenze The participation to the Assembly and Conference is allowed only by presenting the letter of invitation www.lifebeyondtourism.org/evento/946 19th General Assembly and International Conference of the Fondazione Romualdo Del Bianco Life Beyond Tourism Travel for Dialogue ® HERITAGE for PLANET EARTH 2017 One Planet, One Origin, Many Cultures, One Shared Destiny, Or None! PROGRAM AT A GLANCE Morning COMMEMORATION CEREMONIES March 11 MAIN EVENT OPENING of the 19th General Assembly of the Fondazione Romualdo Del Afternoon Bianco PANEL SESSION on TRAVEL “Smart Travel for Dialogue” INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE: parallel sessions Morning “Smart Travel, Smart Architecture, Heritage and its Enjoyment for Dialogue” March 12 Afternoon PRESENTATION of the Life Beyond Tourism Model INTRODUCTION to the web-app <DelBianco CitySmart> March 13 Morning WORKING STATION Life Beyond Tourism Model WORKING STATION web app <DelBianco CitySmart> PATRONAGES [updated on February 16, 2017] ITALIAN AUTHORITIES MAECI - Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale MIBACT – Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo Regione Toscana Municipality of Florence -

Posti INFANZIA

SCUOLA DELL'INFANZIA - DISPONIBILITA' SUPPLENZE GPS A.S. 2021/22 Tipo di Posti al Posti al Ore Sede Denominazione Scuola Comune posto 31/8 30/6 Residue FIEE260008 DD Fucecchio FUCECCHIO AN 2 10 FIEE260008 DD Fucecchio FUCECCHIO EH 4 FIIC80800B IC Marradi MARRADI AN 1 FIIC80800B IC Marradi MARRADI EH 13 GAMBASSI FIIC809007 Ic Gambassi Terme AN 12 TERME GAMBASSI FIIC809007 Ic Gambassi Terme EH 2 13 TERME CAPRAIA E FIIC81000B IC Capraia e Limite AN LIMITE CAPRAIA E FIIC81000B IC Capraia e Limite EH 1 LIMITE MONTELUPO FIIC811007 IC Montelupo Fiorentino AN 1 FIORENTINO MONTELUPO FIIC811007 IC Montelupo Fiorentino EH 13 FIORENTINO FIIC812003 IC Gandhi FIRENZE AN 2 FIIC812003 IC Gandhi FIRENZE EH 2 12 FIIC81300V IC Amerigo Vespucci FIRENZE AN 1 FIIC81300V IC Amerigo Vespucci FIRENZE EH 5 13 FIIC81400P IC Dicomano DICOMANO AN FIIC81400P IC Dicomano DICOMANO EH 1 FIIC81500E IC Vicchio VICCHIO AN 1 FIIC81500E IC Vicchio VICCHIO EH 1 2 FIIC81500E IC Vicchio VICCHIO HN 1 FIIC81600A IC Firenzuola FIRENZUOLA AN 3 FIIC81600A IC Firenzuola FIRENZUOLA EH 1 1 MONTESPERTOL FIIC817006 IC Montespertoli AN I MONTESPERTOL FIIC817006 IC Montespertoli EH 1 I BARBERINO DI FIIC818002 IC Barberino Di Mugello AN 1 MUGELLO BARBERINO DI FIIC818002 IC Barberino Di Mugello EH 1 2 MUGELLO BARBERINO FIIC81900T IC Tavarnelle AN 1 TAVARNELLE BARBERINO FIIC81900T IC Tavarnelle EH 2 1 12 TAVARNELLE FIIC820002 IC Fiesole FIESOLE AN 2 FIIC820002 IC Fiesole FIESOLE EH 1 2 FIIC82100T IC Campi - Giorgio La Pira CAMPI BISENZIO AN 1 FIIC82100T IC Campi - Giorgio La Pira CAMPI BISENZIO -

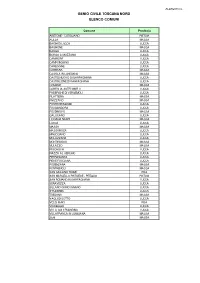

Allegato C Genio Civile Toscana Nord Elenco Comuni

ALLEGATO C GENIO CIVILE TOSCANA NORD ELENCO COMUNI Comune Provincia ABETONE - CUTIGLIANO PISTOIA AULLA MASSA BAGNI DI LUCCA LUCCA BAGNONE MASSA BARGA LUCCA BORGO A MOZZANO LUCCA CAMAIORE LUCCA CAMPORGIANO LUCCA CAREGGINE LUCCA CARRARA MASSA CASOLA IN LUNIGIANA MASSA CASTELNUOVO DI GARFAGNANA LUCCA CASTIGLIONE DI GARFAGNANA LUCCA COMANO MASSA COREGLIA ANTELMINELLI LUCCA FABBRICHE DI VERGEMOLI LUCCA FILATTIERA MASSA FIVIZZANO MASSA FORTE DEI MARMI LUCCA FOSCIANDORA LUCCA FOSDINOVO MASSA GALLICANO LUCCA LICCIANA NARDI MASSA LUCCA LUCCA MASSA MASSA MASSAROSA LUCCA MINUCCIANO LUCCA MOLAZZANA LUCCA MONTIGNOSO MASSA MULAZZO MASSA PESCAGLIA LUCCA PIAZZA AL SERCHIO LUCCA PIETRASANTA LUCCA PIEVE FOSCIANA LUCCA PODENZANA MASSA PONTREMOLI MASSA SAN GIULIANO TERME PISA SAN MARCELLO PISTOIESE - PITEGLIO PISTOIA SAN ROMANO IN GARFAGNANA LUCCA SERAVEZZA LUCCA SILLANO GIUNCUGNANO LUCCA STAZZEMA LUCCA TRESANA MASSA VAGLI DI SOTTO LUCCA VECCHIANO PISA VIAREGGIO LUCCA VILLA COLLEMANDINA LUCCA VILLAFRANCA IN LUNIGIANA MASSA ZERI MASSA ALLEGATO C GENIO CIVILE VALDARNO SUPERIORE ELENCO COMUNI Comune Provincia ANGHIARI AREZZO AREZZO AREZZO BADIA TEDALDA AREZZO BAGNO A RIPOLI FIRENZE BARBERINO DI MUGELLO FIRENZE BIBBIENA AREZZO BORGO SAN LORENZO FIRENZE BUCINE AREZZO CAPOLONA -CASTIGLION FIBOCCHI AREZZO CAPRESE MICHELANGELO AREZZO CASTEL FOCOGNANO AREZZO CASTEL SAN NICCOLO' AREZZO CASTELFRANCO - PIANDISCO' AREZZO CASTIGLION FIORENTINO AREZZO CAVRIGLIA AREZZO CHITIGNANO AREZZO CHIUSI DELLA VERNA AREZZO CIVITELLA IN VAL DI CHIANA AREZZO CORTONA AREZZO DICOMANO -

Toscana Ovvero Terra D'arte E Di Cultura, Casa

www.turismo.intoscana.it Regione Toscana Regione oscana ovvero terra d’arte e di cultura, casa che racconta, incanta e si riflette nel fare della gente da Vinci e Michelangelo sono solo alcuni dei grandi Tdi culture antichissime, culla della civiltà toscana, accogliente e riservata al tempo stesso, maestri d’arte e di scienza. Visitare la Toscana occidentale e della lingua italiana. Qui il viaggiatore innamorata della sua terra, che ha reso il lavoro diventa quindi un’esperienza unica nello scoprire può vivere un’esperienza unica a contatto con un quotidiano e la cura del paesaggio vere forme d’arte. le case dei grandi artisti, le dimore patrizie, le enorme patrimonio storico-artistico disseminato Terra natale di geni che hanno lasciato attraverso cattedrali della fede, vivendo in una natura e in una su tutto il territorio, in grado di unire bellezza, le loro opere una ricchezza ineguagliabile all’intera terra che vanta molti siti riconosciuti patrimonio ricchezza e varietà, scoprendo i valori di una storia umanità: Galileo Galilei e Giacomo Puccini, Leonardo mondiale UNESCO. BORGHI-BANDIERE ARANCIONI E GIOIELLI D’ITALIA • Anghiari (AR) • Peccioli (PI) • San Gimignano (SI) • Castelfranco Piandiscò (AR) • Volterra (PI) • Trequanda (SI) • Castiglion Fiorentino (AR) • Pomarance (PI) • Sarteano (SI) • Loro Ciuffenna (AR) • Castelnuovo Val di Cecina (PI) • Collodi (PT) • Lucignano (AR) • Buonconvento (SI) • Cutigliano (PT) • Ortignano Raggiolo (AR) • Casole d’Elsa (SI) • Isola del Giglio - Giglio Castello (GR) • Poppi (AR) • Castelnuovo Berardenga -

Sheet1 Page 1 APPELLO NO EOLICO SECONDO ELENCO DI SOTTOSCRITORI AL 16.3.2021 Baccetti Silvia Firenze Baggiani Luigi Firenze Barb

Sheet1 APPELLO NO EOLICO SECONDO ELENCO DI SOTTOSCRITORI AL 16.3.2021 Baccetti Silvia Firenze Baggiani Luigi Firenze Barbugli Laura estero iscritta AIRE Vicchio Bargoni Maurizio Vicchio Belardi Grazia Pontassieve Bernoni Margherita Borgo San Lorenzo Bertieri Sandra Dicomano Berveglieri Alessandro Vaglia Biagioni Roberto Vicchio Bolognesi Simone Vicchio Bonanni Franco Vicchio Bonanni Paolo Borgo San Lorenzo Bonanni Teresa Vicchio Boncompagni Rita Borgo San Lorenzo Bosi Sara Dicomano Bracali Monica Firenze Bruttomesso Nyima San Godenzo Bucelli Laura Borgo San Lorenzo Cacopardo Augusto Firenze Camasta Antonio Rufina Cannavale Tommaso Vicchio Cannone Donato Dicomano Cantini Gastone Vicchio Capone Simone Borgo San Lorenzo Cappellini Simona Vicchio Caruana Stefano Borgo San Lorenzo Casalati Lucia Dicomano Cavaciocchi Enzo Borgo San Lorenzo Cecconi Fabrizio Vicchio Cecconi Stefano Vicchio Cerboni Antonio Borgo San Lorenzo Certini Carlo Dicomano Ciucchi Debora Vicchio Ciucchi Ida Dicomano Ciucchi Silvia Calenzano Consolati Enrico San Godenzo Contreras Saida Dicomano D’Angelo Annamaria Scarperia e San Piero Engaz Martina Pontassieve Eredi Leonardo Firenze Fabbiani Lorenzo Vicchio Fabbri Amos Borgo San Lorenzo Fabbri Beppe Borgo San Lorenzo Fabbrucci Alberto Dicomano Fabbrucci Alessandra San Godenzo Facchinetti Maria Rosa Dicomano Ferlato Giuseppe Volterra Ferracci Sara Vicchio Ferretti Stefania San Godenzo Fornai Flavia Dicomano Franceschi Sonia Vicchio Page 1 Sheet1 Francini Paolo Scarperia e San Piero Fratti Alejandra Scarperia e San Piero Gamberi -

Oggetto: Comune Di Figline E Incisa Valdarno (FI) – Conferenza

REGIONE TOSCANA Direzione Urbanistica e Politiche Abitative Giunta Regionale Settore Tutela, Riqualificazione e Valorizzazione del Paesaggio OGGETTO: Unione Montana dei Comuni del Mugello (FI) – Conferenza paesaggistica ai sensi dell'art. 21 della “Disciplina del Piano” del PIT con valenza di Piano Paesaggistico relativa alla conformazione al PIT-PPR del Piano Strutturale Intercomunale Quinta Seduta – 08/06/2020 Verbale della Riunione Nel rispetto delle misure restrittive di contrasto alla diffusione del Covid-19, di cui al DPCM 11/03/2020 e della DGR n. 324 del 11/03/2020 e successivi atti, la presente seduta di Conferenza si tiene in modalità videoconferenza mediante il collegamento al seguente link: https://rtoscana.whereby.com/s-trv-paesaggio. Il giorno 08/06/2020 sono quindi presenti in videoconferenza i seguenti membri in rappresentanza degli organi competenti convocati: per la Regione Toscana: arch. Domenico Bartolo Scrascia, Dirigente del Settore Tutela, Riqualificazione e Valorizzazione del Paesaggio; arch. Beatrice Arrigo, PO del Settore Tutela, Riqualificazione e Valorizzazione del Paesaggio; per la Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti, Paesaggio per la Città Metropolitana di Firenze e le Province di Pistoia e Prato: arch. Paola Ricco, funzionario Responsabile del Procedimento, all’uopo delegata. Alla riunione sono inoltre invitati e presenti: per l’Unione Montana dei Comuni del Mugello: Arch. Giuseppe Rosa, Responsabile del Procedimento; Giampaolo Buti Sindaco del Comune di Firenzuola; Davide Giovannini Assessore Comune di Firenzuola; Arch. Martina Celoni Ufficio Unico di Piano e referente Comune di Dicomano; Geom. Romano Chiocci Ufficio Unico di Piano e referente Comune di Borgo San Lorenzo. Sono inoltre presenti per il Gruppo esterno di progettazione: arch. -

Regolamento Zonale Per Accreditamento Dei Servizi Alla

UNIONE MONTANA dei COMUNI del MUGELLO Barberino di Mugello – Borgo S. Lorenzo – Dicomano – Firenzuola – Marradi – Palazzuolo sul Senio – Scarperia e San Piero - Vicchio Regolamento zonale per l’autorizzazione al funzionamento e l’accreditamento dei servizi educativi per la prima infanzia del Mugello SOMMARIO Art. 1 Oggetto Art. 2 Definizioni Art. 3 Ambito di applicazione Art. 4 Soggetti interessati Art. 5 Requisiti per l’autorizzazione al funzionamento Art. 6 Requisiti per l’accreditamento Art. 7 Istituzione, composizione e funzionamento della Commissione zonale multi-professionale Art. 8 Documentazione utile per la domanda di autorizzazione al funzionamento Art. 9 Fasi e tempi del procedimento di autorizzazione al funzionamento Art. 10 Documentazione utile per la domanda di accreditamento Art. 11 Fasi e tempi del procedimento di accreditamento Art.12 Verifica dei requisiti per i servizi a titolarità pubblica Art. 13 Forma e contenuti del provvedimento Art. 14 Durata, rinnovo e decadenza Art. 15 Informazione e vigilanza UNIONE MONTANA dei COMUNI del MUGELLO Barberino di Mugello – Borgo S. Lorenzo – Dicomano – Firenzuola – Marradi – Palazzuolo sul Senio – Scarperia e San Piero - Vicchio Art. 1 Oggetto Oggetto del presente regolamento è la materia dell’autorizzazione al funzionamento e dell’accreditamento dei servizi educativi per la prima infanzia secondo le disposizioni di cui alla Legge Regionale n. 32/2002 e del relativo regolamento attuativo 41/R 30 luglio 2013. Il presente regolamento, approvato con Decisione n. 1 del 26/03/2014 .da parte della Conferenza dell’Istruzione della Zona del Mugello, ha vigore nell’intero territorio della zona, in ragione e per conseguenza delle decisioni in tal senso assunte dagli Organi Consiliari dei Comuni di Barberino di Mugello, Borgo San Lorenzo, Dicomano, Firenzuola, Marradi, Palazzuolo sul Senio, Scarperia e San Piero e Vicchio (delibera C.C. -

TWELVE ITINERARIES to VISIT FLORENCE with the Art Historian and Painter ELISA MARIANINI

TWELVE ITINERARIES TO VISIT FLORENCE with the art historian and painter ELISA MARIANINI Half day (about 3 hours, maximum 4 hours) Itinerary 1 On the trail of the Medici’s family We can visit the Medici’s quarter starting from Palazzo Medici Riccardi, the first residence of the Medici family. There, we can admire the palace, the Cappella dei Magi by Benozzo Gozzoli and the Galleria degli specchi with the extraordinary Baroque frescoes by Luca Giordano. Then we can visit the Basilica of San Lorenzo, where Brunelleschi and Michelangelo worked, which includes important masterpieces by Donatello, Verrocchio, Bronzino, Rosso Fiorentino. It can also be found the burial place of the Medici's ancestor in the stupendous Old Sagrestia, Brunelleschi's Renaissance masterpiece. Itinerary 2 Discovering the religious heart of Florence We can visit the inside of the Florentine Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore and the ancient Crypt of Santa Reparata, where Brunelleschi is buried. We can also climb up the Dome, the highest point of the city, and visit the Baptistery of San Giovanni. The itinerary continues in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo which has been recently restored and renovated. Here you can admire the original famous bronze doors of the Baptistery and the sculptures of Arnolfo di Cambio, as well as many other important artists who adorned the original façade, before that it was destroyed to build the current one by Emilio De Fabris in the mid-nineteenth century in neo-gothic style. Within the Museum there are works such as the Maddalena of Donatello, the Pietà by Michelangelo, and the Donatello and Luca della Robbia’s Cantories. -

Documento Preliminare Ai Sensi Dell'art.23 Della L.R. N. 10/2010

Art. 23 della L.R. 10/2010 Sindaco Proge sta Federico Ignes Arch.Silvia Viviani Assessore urbanis ca e edilizia Collaboratori al proge o Marco Casa Arch. Francesca Masi Arch. Teresa Arrighe Responsabile del procedimento Dante Albisani Aspe geologici, geomorfologici e ididrologico idraulici GaGarante della comunicazione Geotecno studio associato Maria Cris na Can ni Se ore servizi tecnici VAS - Documento preliminare Indice 1 LA VAS: RIFERIMENTI NORMATIVI E CONTENUTI.....................................................................................................3 1.1 Contenuti generali della VAS.............................................................................................................................3 1.2 Contenuti del Rapporto Ambientale..................................................................................................................5 1.3 Riferimenti normativi.......................................................................................................................................6 2 CARATTERISTICHE DEL TERRITORIO..........................................................................................................................7 2.1 Il territorio comunale di Scarperia e San Piero a Sieve nell'ambito territoriale dell'UTOE 3 del PSIM...................7 2.2 Il Mugello, Scarperia e San Piero a Sieve nella Monografia “MUGELLO E ROMAGNA TOSCANA” del PTC della Provincia di Firenze...........................................................................................................................................................7 -

SUAP Sportello Unico Attività Produttive

UNIONE MONTANA dei COMUNI del MUGELLO Barberino di Mugello – Borgo S. Lorenzo – Dicomano – Firenzuola – Marradi – Palazzuolo sul Senio – Scarperia e San Piero – Vicchio S.U.A.P. Sportello Unico Attività Produttive ATTO SUAP n. 71/2020 del 18/6/2020 Oggetto:Richiesta di modifica e rinnovo di Autorizzazione Unica ambientale per impianto di gestione rifiuti pericolosi e non . Localizzazione intervento: Via della Resistenza n. 4 Loc. I Piani Comune di Vicchio (Fi). Richiedente: ECOLOGIA TRASPORTI DI QUINDICI ROSARIA & C. Sas Pratica SUAP: 455/2019 IL RESPONSABILE DELLO SPORTELLO UNICO PER LE ATTIVITA' PRODUTTIVE Vista la documentazione relativa all’istanza in oggetto e le dichiarazioni nella stessa contenute, pervenute a questo SUAP in data 29/03/2019, con prot. n. 6002 del 29/03/2019, da ECOLOGIA TRASPORTI DI QUINDICI ROSARIA & C. Sas, P.Iva: 04269630481, nella persona del Legale Rappresentante pro tempore, con sede legale in Via Giugni snc, Comune di Vicchio (FI); Considerato che, a seguito di verifica formale e con le modalità previste dal Regolamento di funzionamento del SUAP, in data 02/04/2019 la pratica è stata resa disponibile a Regione Toscana Direzione Ambiente ed Energia - Settore Autorizzazione Ambientali, oltre agli uffici amministrativi competenti, per l'avvio della propria istruttoria e il rilascio del relativo provvedimento; Visto: - il Decreto Dirigenziale n. 8352 e la relativa documentazione, rilasciata da Regione Toscana in data 09/06/2020 e pubblicata all'interno della pratica SUAP in oggetto, in data 16/06/2020; Visti inoltre: - la normativa di settore in merito agli endoprocedimenti attivati; - il D.Lgs. 18 agosto 2000, n. -

Avviso Di Appalto Aggiudicato

AVVISO DI APPALTO AGGIUDICATO Amministrazione appaltante ed aggiudicatrice: Consorzio di Bonifica 3 Medio Valdarno, sede legale in Firenze, Via Giuseppe Verdi n. 16, Codice Fiscale 06432250485. Procedura di affidamento: Procedure negoziate senza bando ex art. 36 c. 2 lett b e c) d. lgs. 50/2016 finalizzate alla stipula di numero due accordi quadro e precisamente: Oggetto: 1) Lotto 13_1_38: accordo quadro per l’affidamento di interventi di m.o. di tipo incidentale lungo il reticolo idrografico in gestione al CBMV ex comprensorio 21 Val d’Elsa (lavori di tipo forestale), di importo complessivo fino a concorrenza di € 122.919,90 (di cui € 117.100,00 come importo lavori ed € 5.819,90 per oneri della sicurezza) (CIG: 6839806278). 2) Lotto 13_1_66: accordo quadro per l’affidamento di interventi di m.o. di tipo incidentale lungo il reticolo idrografico in gestione al CBMV nel bacino del T. Mugnone e del T. Sieci (lavori di tipo forestale), di importo complessivo fino a concorrenza di € 69.790,00 (di cui € 66.450,00 come importo lavori ed € 3.340,00 per oneri della sicurezza) (CIG: 6839829572). Determina a contrarre, ex art. 32 co. 2 del D.Lgs 50/2006: Determina del Dirigente n. 507 del 19/10/2016. Operatori economici invitati: STELLA MAURIZIO Via Trucione, 4/2 - Montespertoli (FI) BAGLIONI MAURO Via Pisana, 623 - Firenze COOPERATIVA RURALE CASOLESE SOC. COOP A R. L. - Loc. Cavallano Fontanella, 8 - 53031 Casole d'Elsa (SI) AZIENDA AGRICOLA COLOGNOLE DI G. SPALLETTI SOC. SGR. A R.L. - Via del Palagio, 15 Pontassieve (FI) AGRICOLA FORESTALE ORLANDINI ANTONIO Via Saturnana, 50 - Pistoia FAGGIOLI VALENTINO - Via Volterrana, 269 – San Casciano Val di Pesa (FI) AZIENDA AGRICOLA DI PALMA ANTONIO TONINO - Via di Castello Loc. -

Report Piano Ispezioni Mensili Marzo 2017

1 di 67 REPORT PIANO ISPEZIONI MENSILI MARZO 2017 PARTI D'IMPIANTO ISPEZIONATE COD. IMPIANTO DENOMINAZIONE MESE COMUNE VIA/PIAZZA RETE RETE BP IDU IDU GRUPPO DISTRIBUZIONE IMPIANTO DISTRIBUZIONE ISPEZIONE AP/MP INTERRATO AEREO DI MISURA 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa LOCALITA' CIPRESSINO 435,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa LOCALITA' LINARI SANTA 42,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 MARIA 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa LOCALITA' SANT' APPIANO 537,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa PIAZZA LETO FRATINI ( VICO 14,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 D' ELSA ) 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa PIAZZA SANT' ANDREA ( VICO 11,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 D' ELSA ) 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa PIAZZA TORRIGIANI ( VICO D' 101,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 ELSA ) 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa S.C. DI LINARI 2.652,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa S.C. DI POPPIANO 604,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa S.C. DI SANT' APPIANO 1.772,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 35128 Barberino Val d'Elsa 03/2017 Barberino Val d'Elsa S.R.