Fetishizing Blackness: the Relationship Between Consumer Culture And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: an Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A

Penn State International Law Review Volume 23 Article 15 Number 4 Penn State International Law Review 5-1-2005 International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A. Yasmine Rassam Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Recommended Citation Rassam, A. Yasmine (2005) "International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 23: No. 4, Article 15. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol23/iss4/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A. Yasmine Rassam* I. Introduction The prohibition of slavery is non-derogable under comprehensive international and regional human rights treaties, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights'; the International Covenant on Civil and * J.S.D. Candidate, Columbia University School of Law. LL.M. 1998, Columbia University School of Law; J.D., magna cum laude, 1994, Indiana University, Bloomington; B.A. 1988, University of Virginia. I would like to thank the Columbia Law School for their financial support. I would also like to thank Mark Barenberg, Lori Damrosch, Alice Miller, and Peter Rosenblum for their comments and guidance on earlier drafts of this article. I am grateful for the editorial support of Clara Schlesinger. -

No. 280 October 11

small screen News Digest of Australian Council on Children and the Media (incorporating Young Media Australia) ISSN: 0817-8224 No. 280 October 2011 Classification update & call for action found on our website at Two significant policy reviews related asking about the process by which older http://www.youngmedia.org.au/pdf/me- to classification reach critical points this very violent games will be reclassified into dia_releases/Nov11_ALRC-proposals.pdf the new R18+ category (as promised). week. An article on this topic which appeared on- One is the review of the classification The second review is the Australian Law line in The National Times and also in The guidelines for computer games (includ- Reform Commission Review of the Na- Age, can be found on Page 6 of this small ing the proposed introduction of a new tional Classification Scheme. Their propos- screen. R18+ category). The “agreed” proposed als are out for public comment by Novem- new guidelines were released by the Min- ber 18 . ACCM wins Childrens Week Award Australian Council on Children and the ister for Home Affairs, The Hon Brendan ACCM comment: Media has won a 2011 Childrens Week O’Connor, on Friday Nov 4. [http://www. ACCM is disturbed by the underlying phi- Award for the Know Before You Go Movie classification.gov.au/www/cob/rwpattach. losphy of deregulation (that also underpins Review service for a significant contribu- nsf/VAP/] and will be debated at the meet- the Convergence Inquiry), and the argu- tion to the development and well–being ing of Federal, State and Territory Ministers ments that it’s too unwieldy and costly for of children, through provision of easily for Law and Justice in Hobart on Nov.18th. -

“The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space”: the Rise and Fall of The

Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ University of North Carolina Asheville “The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space”: The Rise and Fall of the Paper Dress in 1960s American Fashion A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History In Candidacy for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History By Virginia Knight Asheville, North Carolina November 2014 1 A woman stands in front of a mirror in a dressing room, a sales assistant by her side. The sales assistant, with arms full of clothing and a tape measure around her neck, beams at the woman, who is looking at her reflection with a confused stare. The woman is wearing what from the front appears to be a normal, knee-length floral dress. However, the mirror behind her reveals that the “dress” is actually a flimsy sheet of paper that is taped onto the woman and leaves her back-half exposed. The caption reads: “So these are the disposable paper dresses I’ve been reading about?” This newspaper cartoon pokes fun at one of the most defining fashion trends in American history: the paper dress of the late 1960s.1 In 1966, the American Scott Paper Company created a marketing campaign where customers sent in a coupon and shipping money to receive a dress made of a cellulose material called “Dura-Weave.” The coupon came with paper towels, and what began as a way to market Scott’s paper products became a unique trend of American fashion in the late 1960s. -

Bdsm) Communities

BOUND BY CONSENT: CONCEPTS OF CONSENT WITHIN THE LEATHER AND BONDAGE, DOMINATION, SADOMASOCHISM (BDSM) COMMUNITIES A Thesis by Anita Fulkerson Bachelor of General Studies, Wichita State University, 1993 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Anita Fulkerson All Rights Reserved Note that thesis work is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. Only the author has the legal right to publish, produce, sell, or distribute this work. Author permission is needed for others to directly quote significant amounts of information in their own work or to summarize substantial amounts of information in their own work. Limited amounts of information cited, paraphrased, or summarized from the work may be used with proper citation of where to find the original work. BOUND BY CONSENT: CONCEPTS OF CONSENT WITHIN THE LEATHER AND BONDAGE, DOMINATION, SADOMASOCHISM (BDSM) COMMUNITIES The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies _______________________________________ Ron Matson, Committee Chair _______________________________________ Linnea Glen-Maye, Committee Member _______________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member _______________________________________ Patricia Phillips, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my Ma'am, my parents, and my Leather Family iv When you build consent, you build the Community. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my adviser, Ron Matson, for his unwavering belief in this topic and in my ability to do it justice and his unending enthusiasm for the project. -

![[Laundry Workers]: a Machine Readable Transcription](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9035/laundry-workers-a-machine-readable-transcription-219035.webp)

[Laundry Workers]: a Machine Readable Transcription

Library of Congress [Laundry Workers] Beliefs and Customs - Folk Stuff FOLKLORE NEW YORK Forms to be Filled out for Each Interview FORM A Circumstances of Interview STATE New York NAME OF WORKER Vivian Morris ADDRESS 225 West 130th Street, N.Y.C. DATE March 9, 1939 SUBJECT Laundry Workers 1. Date and time of [?] Observation March 8th. 11:10 A.M. to 12 Noon. 2. Place of [?] observation West End Laundry 41th Street between 10th & 11th Avenues. 3. Name and address of informant 4. Name and address of person, if any, who put you in touch with informant. 5. Name and address of person, if any, accompanying you [Laundry Workers] http://www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh2.22040205 Library of Congress 6. Description of room, house, surroundings, etc. FOLKLORE NEW YORK FORM C Text of Interview (Unedited) STATE New York NAME OF WORKER Vivian Morris ADDRESS 225 West 130th Street, N.Y.C. DATE March 9, 1939 SUBJECT Laundry Workers LAUNDRY WORKERS The foreman of the ironing department of the laundry eyed me suspiciously and then curtly asked me, “what you want?” I showed him a Laundry Workers Union card (which I borrowed from an unemployed lanudry worker, in order to insure my admittance) and told him that I used to work in this laundry and I thought I would drop in and take a friend of mine who worked there, out to lunch. He squinted at the clock and sad, “Forty minutes before lunch time. Too hot in here and how. Better wait outside.” “But,” I remonstrated, “the heat doesn't bother me. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile

FETISHISM AND THE CULTURE OF THE AUTOMOBILE James Duncan Mackintosh B.A.(hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1985 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication Q~amesMackintosh 1990 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1990 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : James Duncan Mackintosh DEGREE : Master of Arts (Communication) TITLE OF THESIS: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman : Dr. William D. Richards, Jr. \ -1 Dr. Martih Labbu Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Dr. Alison C.M. Beale Assistant Professor \I I Dr. - Jerry Zqlove, Associate Professor, Department of ~n~lish, External Examiner DATE APPROVED : 20 August 1990 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Dissertation: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile. Author : -re James Duncan Mackintosh name 20 August 1990 date ABSTRACT This thesis explores the notion of fetishism as an appropriate instrument of cultural criticism to investigate the rites and rituals surrounding the automobile. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

Laundry Solutions

GIRBAU INC. WASHER-EXTRACTORS CONTINUOUS LAUNDRY SOLUTIONS WASHING SYSTEMS FOR HOSPITALITY LAUNDRIES DRYING TUMBLERS LAUNDRY SYSTEMS DESIGNED SPECIFICALLY FOR ALL SEGMENTS IRONING SYSTEMS OF THE HOSPITALITY INDUSTRY FEEDERS, FOLDERS & STACKERS THE TOTAL LAUNDRY SOLUTION FOR COMPLETE HOSPITALITY SATISFACTION At Continental Girbau Inc., we work to perfectly fit laundry equipment to the unique production, space, labor, workflow and energy needs of our clients in the hospitality industry. Our expansive product offering, including Continental Girbau and Girbau Industrial washing, drying, linen handling and ironing systems, work seamlessly together for the ultimate in reduced energy and labor costs, bolstered productivity, unmatched programmability, superior durability and ease-of-use. YOUR PRODUCTION NEEDS MATTER. We work closely with your hotel to deliver the perfect equipment mix — matching your unique needs completely. Our proven and dependable, high-performance lines of laundry equipment include the super high-volume TBS-50 Continuous Batch Washing System; high-, mid- and low-volume washer-extractors in 20- to 255-pound capacities; complementing stacked and single-pocket dryers; feeders; as well as ironing systems, folders, and stackers. GOING ‘GREEN’ MAKES GOOD BUSINESS SENSE. Thanks to our high-performance laundry equipment, water reclamation systems and ozone technologies, hotels and resorts reduce utility and labor costs, elevate green marketability and appeal, and bolster laundry productivity and quality. No wonder our laundry products qualify for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) credits, which can contribute to LEED certification! GUEST LAUNDRY SOLUTIONS FOR HAPPY GUESTS. Our small-load commercial laundry solutions are perfect for guest laundries. Choose from three powerhouse brands — Continental, LG and Econ-O — for proven durability, quiet operation, superior efficiency and ease-of-use. -

Foul Chutes: on the Archive Downriver Sarah Minor

Ninthletter.com Special Feature, October 2018 Foul Chutes: On the Archive Downriver Sarah Minor ~ The old house where I was raised for a time was exactly one hundred years older than my sister. It stood facing the river across from another white house where, in 1932, the LaRosa family had installed the very first laundry chute in Rockford, Illinois, long before our city was named the country’s third most miserable. By the mid-’90s a highway ran between my family’s ailing Victorian and its Mississippi tributary and for ten years we lived up there, where Brown’s Road ended, where the street might have tipped over the hill and rushed across the stinking river if In June of 1998, while he was renovating his someone hadn’t changed his mind. We wore kitchen-scissor home in St. Louis, Joseph Heathcott discovered bangs and liked to hang out at the dead end beside our a collection of trash in the cavity between his porch—a bald gully stained with mulberries where we played pantry and his laundry chute. It was a stack of at being orphaned, though we were far from it—past the paper scraps with sooty edges that were just broken curb where lost cars drew circles in the gravel. beginning to stick and combine. There was a box of We preferred the dead end to our yard because it collected playing cards, a train ticket from Kansas, a receipt, a the street trash and there we could sort out the best of it. diary entry, and a laundry ticket. -

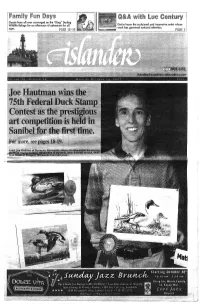

Va Islander.Coni

nir; Guests feurr c!i over cor.\fsrc<s6 or; ihe "Dirtj" Barling V'/iidiife ketuge i'-">r en cfse"~ocn cf adventure ?o: c'i I Os? {o iisiow Hie c.-cscinricd and ii;novf:five orris* whose v/crk has aarr.ered ntriio.iol ctferitio'i. va islander.coni Artist Joe Hautrrtan of Plymouth, Minnesota collects his bfue ribbon for winning the Duck Stamp Contest Harold Roe of Syfvania, Ohio finished second, while *^ot Sform of Freeport. Minnesota took third prize. - ! •. RESTAURANT 8r LOUNGE Local celebs show off footwork at WishMakers Ball '!• As the hit television show and former Ft. Myers Police Chief "Dancing With The Stars*' begins its Larry Hart. fall season, our local news personali- The evening will showcase a ties and community leaders are gear- silent auction of fantasy items it ing up for "Dancing With Our Stars" including an apartment overlooking Togo event. the Adriatic Sea, an Indy Car VIP tnc> Local celebrities will be compet- package and an autographed guitar What; ing at the 2007 WishMakers Ball — donated by rocker Sammy Hagar. 2007 WishMakers Ball © "where the magic of dance makes Other items on the auction block o wishes come true" — to benefit the include trips with airfare and VIP When: Make-A-Wish Foundation of tickets to the Masters Tournament, Saturday, Oct. 27 •E s Southern Florida. the 2008 Super Bowl, the British This second annual showcase and Open and California Wine Country. Where: Sanibei Harbour Resort and fa celebrity competition will be held on Last year's WishMakers Ball sold Saturday, Oct. -

For Each Kink Indicate with an 'X' Whether You Have Or Haven't Tried the Kink, and Where It Falls in Your Limits

Instructions: For each Kink indicate with an 'x' whether you have or haven't tried the Kink, and where it falls in your limits. Green being a Kink that you are whole heartedly okay with participating in, Soft being a Kink that you are curious about, but would only want to try under the right circumstances, and Hard being a Kink that you are wholeheartedly NOT okay with participating in. If you are unsure of what a Kink is either ask your partner or go online (or wherever) and research it. If there are any notes that you would like to make on any of the Kinks (ex. Experience you had etc.) there is a notes page at the end. Once both you and your partner have completed your lists use this as a tool to start the an indepth conversation of the Kinks that you and your partner are going to be participating in once you start playing. It is okay if you and your partner disagree on certain Kinks, not everyone is going to like the same things in life and that especially goes for peoples Kinks. There are numerous Kinks out there, and while I would like to include everyone of them, almost anything can be turned into a kink so this list does not contain every single kink out there. Kink Tried- Yes Tried-No Interested Green Soft Hard 24/7 Dynamic Adult Baby Diaper Lover (ABDL) Abduction Play Abrasion Play Age Play Anal Fisting Anal Play Anal Plugs Anal Sex Anal Training Asphyxiation Play Ball Gags Bare Bottom Spanking Bare Handed Spanking Bathroom Use Control Beastiality Behaviour Modification Biting Blindfolds Blood Play Boot Blacking Boot Worship Branding