It's Time to ACT: Countering the Impact of Covid-19 on Pupils and Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reformed GCSE, AS and a Level Subjects

Reformed GCSE, AS and A level subject content Government consultation response January 2016 Contents Introduction 3 Overview of reforms 5 Summary of responses received and the Government’s response 7 Astronomy GCSE 8 Business GCSE 12 Economics GCSE 15 Engineering GCSE 17 Geology GCSE 20 Psychology GCSE 22 Sociology GCSE 26 Design and technology AS and A level 28 Environmental science AS and A level 32 History of art AS and A level 34 Music technology AS and A level 38 Philosophy AS and A level 41 Next steps 44 Annex: list of respondents to the consultation 45 2 Introduction On 16 July 2015 the Department for Education published a consultation on proposed content for GCSEs in astronomy, business, economics, engineering, geology, psychology and sociology, and AS and A levels in design and technology, environmental science, history of art, music technology and philosophy. The proposed GCSE subject content aims to provide students with more fulfilling and demanding courses of study; new A level content aims to encourage development of the knowledge and skills needed for progression to undergraduate study and employment. The consultation sought views on the following questions: • whether the revised GCSE content in each subject is appropriate: • whether there is a suitable level of challenge • whether the content reflects what students need to know in order to progress to further academic and vocational education • whether the revised AS and A level content in each subject is appropriate: • whether the content reflects what students need to -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

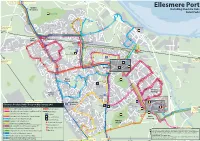

S Cheshire Oaks

Cheshire West & Chester Council Ellesmere Port Area Destination Finder/Map 272 Hooton/Neston 272 M53 1 to Birkenhead/Liverpool 1 X1 2 to Brombrough/Liverpool N M53 ort 359 from Neston High Sch 359CHESTER ROAD h R B5132 o M53 ad B5132 S Childer Ellesmere Port ch oo l (including Cheshire Oaks L a Thornton n Rivacre Road e d Poole Hall Road oa R a ll e ) a r Retail Park) L c d d Rivacre Valley H (M53) r a a d 8 a h oo le t P a o rc od c Country Park o R O o n R u h W J l s Manchester Ship Canal l o e o p W r ( Hillside Drive e 7 River Mersey 0 h NAYLOR RD 7 t 5 vale ss e 5 o N A M Warren Drive Rothe RIVACRE BROW 7 W r F H a D MERSEYTON RD 1 X1 Hillfield Road i 7 r e rw h iv a a a e 272 d ys r t 359 f M53 h a e D e CHESTER ROAD o r R n L L Sweetfiel iv 7 a d G a T ds s e a ld HILLSIDE DRIVE ne e r L y n National fi u t a es ROSSMORE RD EAST e n n r e m Fo e o r w Trains to Hooton/ i Waterways G a d L n Pou nd Road P n n i s n d Museum Birkenhead/ A l a e W Grosvenor Road L an n e R 7 Liverpool t 7 a Ave Rossbank Road t Dock St QUEEN STREET RIVACRE ROAD Station ion Dr Ch es d ter a Livingstone Road Rd o R ROSSMORE ROAD EAST ROSSMORE ROAD WEST X1 7 d l 7 O e i OVERPOOL RD Bailey Avenue l 106 S fi S Woodend Rd s i s Percival Rd t Berwick Road H CHESTER ROAD e Little Ferguson Ave Crossley o JohnGrace St Rd s i R l Straker Avenue e R l o c Ave v WESTMINSTER RD a i S r eym d r Little Sutton our e Sutton Drive D s t 106 S k R Station r o a C a 6 HAWTHORNE ROAD Overpool Wilkinson St P l d e 359LEDSHAM ROAD v m e Overpool e a 6 Rd 1 6 GLENWOOD ROAD Av -

A Showstopping Performance of the Producers Read the Full Story on Page 8 Seniors

www.kingschester.co.uk All the latest news from The King’s School, Chester | Spring 2015 The King’s School, colouring their lives forever. Learn more inside... A showstopping performance of The Producers Read the full story on page 8 Seniors A performance to be proud of King’s was crowned the top performing The GCSE results also improved after At GCSE, the decision to no longer include independent school in Chester, following corrections with 47% A*, 77% A*/A grades IGCSEs in the Government’s figures meant the publication of The Sunday Times with King’s girls achieving 52% A*, 78% that King’s score, along with most other Parent Power table for GCSE and A Level A*/A and 97% A*/B grades. academic independent schools, was very results last term. low with 14% achieving five A*-C GCSEs Government League table including Maths and English. Should IGCSEs For the second year running, King’s was In January, the Government League tables be included, the result would be 100%. placed in the top 80 independent schools were released. King’s was the highest in the country. In 2014, it was placed performing School in the Chester area with For further guidance on these performance 5th in the North West and was placed 2nd an A-average point score per A Level entry. tables, visit: for co-educational schools. www.kingschester.co.uk/academicresults The late corrections in examination papers • 100% achieving three A Levels further boosted King’s examination results. • 53% achieving AAB or higher in at The final results for A Level are now 65% least three facilitating subjects A*/A and 87% A*/B with girls at King’s (King’s offers all facilitating subjects) scoring 89% A*/B. -

170382 CVTSA Flyer V4

BECOME AN OUTSTANDING ASSOCIATE TEACHER Train to Teach with Cheshire Vale TSA We will be holding promotional events throughout the year: Tarporley High School 12th Oct 4 - 7pm Queen’s Park High School 19th Oct 4 - 7pm Please book a place by contacting Pam Bailey at [email protected] Applications to School Direct are made through UCAS For further information on how to apply for School Direct in our Alliance E-mail: [email protected] www.cvtsa.co.uk/become-teacher SCHOOL PLACES ON OFFER FOR 2016/17 Bishop Heber High School 3 www.bishopheber.cheshire.sch.uk Blacon High School 5 www.blaconhighschool.net The Catholic High School, Chester 1 www.chsc.cheshire.sch.uk Christleton High School 10 www.christletonhigh.co.uk Ellesmere Port Catholic High School 3 www.epchs.co.uk Hartford Church of England High School 11 www.hartfordhigh.org.uk Helsby High School 5 www.helsbyhigh.org.uk Neston High School 10 www.nestonhigh.cheshire.sch.uk Helsby Hillside Primary School 1 www.helsbyhillside.co.uk Manor House Primary School 1 www.manorhouse.cheshire.sch.uk Frodsham CE Primary School 1 www.frodshamce.cheshire.sch.uk Kingsley Community Primary and Nursery School 1 www.kingsleycp.cheshire.sch.uk Queen’s Park High School 7 www.qphs.cheshire.sch.uk St Nicholas Catholic High School 4 www.st-nicholas.cheshire.sch.uk Tarporley High School 9 www.tarporleyhigh.co.uk Upton-by-Chester High School 3 www.uptonhigh.co.uk Weaverham High School 5 www.weaverham.cheshire.sch.uk WE WILL OFFER PLACES IN THE FOLLOWING SUBJECTS FOR 2016/17 Maths Computer Science (ICT) Music English Drama Geography Biology Art & Design Business Chemistry MFL RE Physics D & T Primary PE History Fees for School Direct are £9,000. -

Rivacre Valley Orienteering Leaflet

During the months of February, March, April and May There are 16 permanent control points in How to find us the woodland slopes will be covered in our Native total with 1-8 being slightly easier to For all passenger travel and timetable information please contact: Cheshire West & Chester Council Bluebells either pushing their way up, in flower or locate and 9-16 a touch more difficult. receding its growth back into the bulb. They are very You will be getting out into lovely susceptible to permanent damage from trampling. countryside –often to places you Please help us to protect this beautiful native woodland wouldn’t otherwise visit and is an Rivacre plant by bearing this in mind and keeping to the main easy painless way of staying fit or g paths if you are using the course during these months. getting in shape if you ‘re not. Orienteering means maps, wooded areas and Orienteering maps are drawn to a large scale Valley adventure. You can run, jog or walk your chosen route most commonly 1:15000 (1cm=150m on the n to the control or wooden posts that you are looking for. ground). The maps are drawn using magnetic If you like excitement, fresh air and exploring the north and are printed in up to 5 i countryside then orienteering could be the sport for standard colours with the features you. There is no better way to find out about being depicted in the legend. r orienteering than to have a go at this fairly easy permanent course at Rivacre Valley Country Park and Black – is used for most man made Local Nature Reserve. -

Newsletter April 2018 Welcome to the April Edition of the Chester School Sport Partnership Newsletter

Newsletter April 2018 Welcome to the April edition of the Chester School Sport Partnership newsletter. A huge congratulations and thank you to all the teams who represented Chester at the Cheshire and Warrington Level 3 School Games this term. We have had a lot of success, with teams showing great determination, passion and respect in their events. A special mention must be made to the children from Waverton Primary School who took part in four competitions over two weeks. Also to Chester Catholic High for sending teams to three events, plus providing the amazing leaders for the tag rugby competition at Chester Rugby Club. PE and School Sport Premium Funding: please can all primary schools ensure that they update their website as the deadline has now passed to publish how you are planning to spend your funds and evidence the impact. We have a busy summer term ahead, if you want to enter any primary competitions, please do so via the Chester SSP website (www.chesterssp.co.uk) - please note that some events are already full. Playground Leaders Course Over the February half term, 27 children from years 5&6 gave up a day of their holidays to attend the Playground Leaders Training Course at Blacon High School. Here they learned about how to deliver playground games and activities to their peers and younger children in their school. The training was a mixture of practical and theory work, looking at the STEP principle and how to be a good leader. The children have now gone back to their schools confident and prepared to begin to help deliver playground games and activities. -

Youth Arts Audit: West Cheshire and Chester: Including Districts of Chester, Ellesmere Port and Neston and Vale Royal 2008

YOUTH ARTS AUDIT: WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER: INCLUDING DISTRICTS OF CHESTER, ELLESMERE PORT AND NESTON AND VALE ROYAL 2008 This project is part of a wider pan Cheshire audit of youth arts supported by Arts Council England-North West and Cheshire County Council Angela Chappell; Strategic Development Officer (Arts & Young People) Chester Performs; 55-57 Watergate Row South, Chester, CH1 2LE Email: [email protected] Tel: 01244 409113 Fax: 01244 401697 Website: www.chesterperforms.com 1 YOUTH ARTS AUDIT: WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER JANUARY-SUMMER 2008 CONTENTS PAGES 1 - 2. FOREWORD PAGES 3 – 4. WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER PAGES 3 - 18. CHESTER PAGES 19 – 33. ELLESMERE PORT & NESTON PAGES 34 – 55. VALE ROYAL INTRODUCTION 2 This document details Youth arts activity and organisations in West Cheshire and Chester is presented in this document on a district-by-district basis. This project is part of a wider pan Cheshire audit of youth arts including; a separate document also for East Cheshire, a sub-regional and county wide audit in Cheshire as well as a report analysis recommendations for youth arts for the future. This also precedes the new structure of Cheshire’s two county unitary authorities following LGR into East and West Cheshire and Chester, which will come into being in April 2009 An audit of this kind will never be fully accurate, comprehensive and up-to-date. Some data will be out-of-date or incorrect as soon as it’s printed or written, and we apologise for any errors or omissions. The youth arts audit aims to produce a snapshot of the activity that takes place in West Cheshire provided by the many arts, culture and youth organisations based in the county in the spring and summer of 2008– we hope it is a fair and balanced picture, giving a reasonable impression of the scale and scope of youth arts activities, organisations and opportunities – but it is not entirely exhaustive and does not claim to be. -

Crewe & Nantwich Health Walks Health Walks Are Aimed at People

Crewe & Nantwich Health Walks Health walks are aimed at people who do little or no exercise to try walking as a way of becoming more active, getting healthier and meeting new people. The walks cover a short distance, taking around 45 minutes, with everyone encouraged to walk at their own pace. Our programme of weekly walks is as follows: Crewe Business Park - Tuesdays 7.00pm during the summer months, 1.00pm from September, beginning from the grass verge on the opposite side of the security office on Electra Way. West End of Crewe - Wednesdays 2.00pm from the car park at the King George Vth playing fields. Wistaston - Thursdays 11.00am from the Woodside Public House car park. Parking is available. Nantwich - Sundays 11.00am from the town centre square near St Mary’s Church. For further details please contact Craig McKeith on 01270 537240 Explore the Whitegate Way The Whitegate Way is the perfect place to walk, cycle, horse ride, have a picnic, bird watch or just do nothing but listen to the wind in the trees and the birds singing! A free leaflet including a site map is available from Whitegate Station. Parking is available at Whitegate Station car park off Clay Lane, Marton near Winsford. 9.00am to 8.00pm April to September, 9.00am to 5.00pm October to March also Winsford and Over car park, New Road off A5018/A54 roundabout, Winsford. For further details contact John Cergnul on 01606 301485, email: [email protected] The Mersey Forest in Cheshire Northwich Community Woodlands is a key part of The Mersey Forest. -

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick Please Use

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick Please use the table below to check whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for a contextual offer. For more information about our contextual offer please visit our website or contact the Undergraduate Admissions Team. School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school which meets the 'Y' indicates a school which meets the Free School Meal criteria. Schools are listed in alphabetical order. school performance citeria. 'N/A' indicates a school for which the data is not available. 6th Form at Swakeleys UB10 0EJ N Y Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School ME2 3SP N Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST2 8LG Y Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton TS19 8BU Y Y Abbey School, Faversham ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent DE15 0JL Y Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool L25 6EE Y Y Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Y N Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge UB10 0EX Y N School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals Abbs Cross School and Arts College RM12 4YQ Y N Abbs Cross School, Hornchurch RM12 4YB Y N Abingdon And Witney College OX14 1GG Y NA Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Y Y Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Y Y Abraham Moss High School, Manchester M8 5UF Y Y Academy 360 SR4 9BA Y Y Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Y Y Acklam Grange -

Ellesmere Port Area Map January 2011 (09.01.11

272 272/274 Neston/Arrowe Park 274 401 401/X11 to Birkenhead/Liverpool M53 1 to Birkenhead/Liverpool 1 X11 N CHESTER ROAD M53 or th Ro B5132 ad M53 B5132 Ellesmere Port Schoo Childer l L (including Cheshire Oaks ane Thornton Rivacre Road d Poole Hall Road oa La R ll Retail Park) Rivacre Valley a cre ard La H a (M53) h Poo le d 8 c ad Country Park o ct Or o o n W R u l J Manchester Ship Canal poo r 7 7 Hillside Drive (Welsh Road) e River Mersey h NAYLOR RD 7S 7S vale oss M Net A550 7 Warren Drive 7S Rothe F RIVACRE BROW W r D H a MERSEYTON RD 1 401 Hillfield Road i 3 7 r r i v ea w 7S h 272 a a e ys rf th L 274X11 d D M53 CHESTER ROAD a r e Ro Sw iv 3 L eet e a ne field Gd a d T s HILLSIDE DRIVE l a s ne r ne fie u y est Road ROSSMORE RD EAST n m a r ee L n Fo r w Trains to Hooton/ a o Ellesmere Port G i lose d n Pound C 7 Road n P L s n Birkenhead/ l 7S d A a Grosvenor Road Boat Museum L e an n e Win R Liverpool t 7 RIVACRE ROAD a Ave t 7S Rossbank Road Dock St QUEEN STREET Station io C n Dr heste r d Livingstone Road Rd 272 a 274 o R 7 7 ROSSMORE ROAD WEST ROSSMORE ROAD EAST 7S 401 7S d l O OVERPOOL RD e i Bailey Avenue i l CHESTER ROAD S 106 f Si Ferguson Av Woodend Rd s t e Crossley s Percival Rd Berwick Road H e Ave o JohnGrace St Rd s il Straker Avenue R R l o c Little 7 ad res Seymour ve Little Sutton Drive WESTMINSTER RD t R Sutton Station 106 S o a Cl HAWTHORNE ROAD ark Dri d S 6 Overpool WILKINSON ST e ive Dr LEDSHAM ROAD Overpool v 6 e el Rd 1 6 X11 Av 272 and n Hillcrest to Black Lion Lane GLENWOOD edarROAD Station 3 401274 -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3