Morocco Page 1 of 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jehovah's Witnesses

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: MAR32111 Country: Morocco Date: 27 August 2007 Keywords: Morocco – Christians – Catholics – Jehovah’s Witnesses – French language This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. What is the view of the Moroccan authorities to Catholicism and Christianity (generally)? Have there been incidents of mistreatment because of non-Muslim religious belief? 2. In what way has the attitude of the authorities to Jehovah’s Witnesses and Christians changed (if it has) from 1990 to 2007? 3. Is there any evidence of discrimination against non-French speakers? RESPONSE 1. What is the view of the Moroccan authorities to Catholicism and Christianity (generally)? Have there been incidents of mistreatment because of non-Muslim religious belief? Sources report that foreigners openly practice Christianity in Morocco while Moroccan Christian converts practice their faith in secret. Moroccan Christian converts face social ostracism and short periods of questioning or detention by the authorities. Proselytism is illegal in Morocco; however, voluntary conversion is legal. The information provided in response to these questions has been organised into the following two sections: • Foreign Christian Communities in Morocco; and • Moroccan Christians. -

MOROCCO COUNTRY REPORT (In French) ETAT DES LIEUX DE LA CULTURE ET DES ARTS

MOROCCO Country Report MOROCCO COUNTRY REPORT (in French) ETAT DES LIEUX DE LA CULTURE ET DES ARTS Decembre 2018 Par Dounia Benslimane (2018) This report has been produced with assistance of the European Union. The content of this report is the sole responsibility of the Technical Assistance Unit of the Med- Culture Programme. It reflects the opinion of contributing experts and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. 1- INTRODUCTION ET CONTEXTE Le Maroc est un pays d’Afrique du Nord de 33 848 242 millions d’habitants en 20141, dont 60,3% vivent en milieux urbain, avec un taux d’analphabétisme de 32,2% et 34,1% de jeunes (entre 15 et 34 ans), d’une superficie de 710 850 km2, indépendant depuis le 18 novembre 1956. Le Maroc est une monarchie constitutionnelle démocratique, parlementaire et sociale2. Les deux langues officielles du royaume sont l’arabe et le tamazight. L’islam est la religion de l’État (courant sunnite malékite). Sa dernière constitution a été réformée et adoptée par référendum le 1er juillet 2011, suite aux revendications populaires du Mouvement du 20 février 2011. Données économiques3 : PIB (2017) : 110,2 milliards de dollars Taux de croissance (2015) : +4,5% Classement IDH (2016) : 123ème sur 188 pays (+3 places depuis 2015) Le Maroc a le sixième PIB le plus important en Afrique en 20174 après le Nigéria, l’Afrique du Sud, l’Egypte, l’Algérie et le Soudan, selon le top 10 des pays les plus riches du continent établi par la Banque Africaine de Développement. -

Hassani-Ouassima-Tesis15.Pdf (4.423Mb)

UNIVERSIDAD PABLO DE OLAVIDE DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA Y TRADUCCIÓN TESIS DOCTORAL LA TRADUCCIÓN AUDIOVISUAL EN MARRUECOS: ESTUDIO DESCRIPTIVO Y ANÁLISIS TRADUCTOLÓGICO Sevilla, 2015 Presentada por: Ouassima Bakkali Hassani Dirigida por: Dr. Adrián Fuentes Luque Esta tesis fue realizada gracias a una beca de la Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional (AECID). AGRADECIMIENTOS La realización de este trabajo de investigación me ha hecho pasar por momentos duros y difíciles, y ha supuesto ser un verdadero reto tanto personal como profesional. Por ello, es menester agradecer y reconocer la ayuda crucial brindada por aquellas personas y que de una manera u otra han contribuido para llevar a buen puerto la presente Tesis. Son muchas las que han estado a mi lado en momentos difíciles y en los que en más de una ocasión pensé tirar la toalla. Pude hacer frente a ellos y he podido seguir adelante y superar todos los obstáculos que se me pusieron en frente. En primer lugar, quiero agradecer al Dr. Adrián Fuentes Luque, quien ha creído y apostado por mí y en el tema de la investigación desde el primer momento, me ha ayudado a mantener el ánimo y ha seguido con lupa e interés todo el proceso de elaboración de la Tesis. 7DPELpQDO&HQWUR&LQHPDWRJUi¿FR0DUURTXtSRUHOPDWHULDOIDFLOLWDGR\ODVHQWUHYLVWDVFRQFHGLGDV en especial al que fuera su director, D. Nouredine Sail, y al Jefe del departamento de Cooperación y Promoción, D. Tariq Khalami. Asimismo, quiero dar un especial agradecimiento a todos los profesionales del sector audiovisual \GHODWUDGXFFLyQDXGLRYLVXDOHQ0DUUXHFRVDORVTXHKHWHQLGRODRFDVLyQ\HOJXVWRGHHQWUHYLVWDUHQ HVSHFLDOD'xD+LQG=NLNGLUHFWRUDGH3OXJ,Q'(O+RXVVLQH0DMGRXELGLUHFWRUGHOSHULyGLFRAlif Post y académico, Dña. Saloua Zouiten, secretaria general de la Fondation du Festival International du )LOPGH0DUUDNHFK',PDG0HQLDULHMHFXWLYRHQOD+DXWH$XWRULWpGH&RPPXQLFDWLRQ$XGLRYLVXHO D. -

MOROCCO Morocco Is a Monarchy with a Constitution, an Elected

MOROCCO Morocco is a monarchy with a constitution, an elected parliament, and a population of approximately 34 million. According to the constitution, ultimate authority rests with King Mohammed VI, who presides over the Council of Ministers and appoints or approves members of the government. The king may dismiss ministers, dissolve parliament, call for new elections, and rule by decree. In the bicameral legislature, the lower house may dissolve the government through a vote of no confidence. The 2007 multiparty parliamentary elections for the lower house went smoothly and were marked by transparency and professionalism. International observers judged that those elections were relatively free from government- sponsored irregularities. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. Citizens did not have the right to change the constitutional provisions establishing the country's monarchical form of government or those designating Islam the state religion. There were reports of torture and other abuses by various branches of the security forces. Prison conditions remained below international standards. Reports of arbitrary arrests, incommunicado detentions, and police and security force impunity continued. Politics, as well as corruption and inefficiency, influenced the judiciary, which was not fully independent. The government restricted press freedoms. Corruption was a serious problem in all branches of government. Child labor, particularly in the unregulated informal sector, and trafficking in persons remained problems. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were no reports that the government or its agents committed any politically motivated killings; however, there were reports of deaths in police custody. -

Sustainability Index 2006/2007

MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2006/2007 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in the Middle East and North Africa MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2006/2007 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in the Middle East and North Africa www.irex.org/msi Copyright © 2008 by IREX IREX 2121 K Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20037 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (202) 628-8188 Fax: (202) 628-8189 www.irex.org Project manager: Leon Morse IREX Project and Editorial Support: Blake Saville, Mark Whitehouse, Christine Prince Copyeditors: Carolyn Feola de Rugamas, Carolyn.Ink; Kelly Kramer, WORDtoWORD Editorial Services Design and layout: OmniStudio Printer: Kirby Lithographic Company, Inc. Notice of Rights: Permission is granted to display, copy, and distribute the MSI in whole or in part, provided that: (a) the materials are used with the acknowledgement “The Media Sustainability Index (MSI) is a product of IREX with funding from USAID and the US State Department’s Middle East Partnership Initiative, and the Iraq study was produced with the support and funding of UNESCO.”; (b) the MSI is used solely for personal, noncommercial, or informational use; and (c) no modifications of the MSI are made. Acknowledgment: This publication was made possible through support provided by the United States Department of State’s Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No. #DFD-A-00-05-00243 (MSI-MENA) via a Task Order by the Academy for Educational Development. Additional support for the Iraq study was provided by UNESCO. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the panelists and other project researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, MEPI, UNESCO, or IREX. -

L'emprise De La Monarchie Marocaine Entre

L'Année du Maghreb III (2007) Dossier : Justice, politique et société ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Thierry Desrues L’emprise de la monarchie marocaine entre fin du droit d’inventaire et déploiement de la « technocratie palatiale » ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Avertissement Le contenu de ce site relève de la législation française sur la propriété intellectuelle et est la propriété exclusive de l'éditeur. Les œuvres figurant sur ce site peuvent être consultées et reproduites sur un support papier ou numérique sous réserve qu'elles soient strictement réservées à un usage soit personnel, soit scientifique ou pédagogique excluant toute exploitation commerciale. La reproduction devra obligatoirement mentionner l'éditeur, le nom de la revue, l'auteur et la référence du document. Toute autre reproduction est interdite sauf accord préalable de l'éditeur, en dehors des cas prévus par la législation en vigueur en France. Revues.org est un portail de revues en sciences humaines et sociales développé par le Cléo, Centre pour l'édition électronique -

CASABLANCA, Morocco Hmed Reda Benchemsi, the 33-Year-Old

Posted July 3, 2007 CASABLANCA, Morocco A hmed Reda Benchemsi, the 33-year-old publisher of the independent Moroccan weekly TelQuel, sensed someone was trying to send him a message. In a matter of months, two judges had ordered him to pay extraordinarily high damages in a pair of otherwise unremarkable defamation lawsuits. It started in August 2005, when a court convicted Benchemsi of defaming pro- government member of parliament Hlima Assali, who complained about a short article that made light of her alleged experience as a chiekha, or popular dancer. At trial, Benchemsi and his lawyer never put up a defense—because they weren’t in court. The judge had reconvened the trial 15 minutes before scheduled and, with no one representing the defense, promptly issued a verdict: two-month suspended jail terms for Benchemsi and another colleague and damages of 1 million dirhams (US$120,000). Two months later, another court convicted Benchemsi of defamation, this time after the head of a children’s assistance organization sued TelQuel and three other Moroccan newspapers for erroneously reporting that she was under investigation for suspected embezzlement. TelQuel, which had already issued a correction and apology, was ordered to pay 900,000 dirhams (US$108,000)—several times the amounts ordered against the other three publications. At the time, the damages were among the highest ever awarded in a defamation case in Morocco—and more than nine times what Moroccan lawyers and journalists say is the national norm in such cases. A puzzled Benchemsi said he learned from a palace source several months later what had triggered the judicial onslaught. -

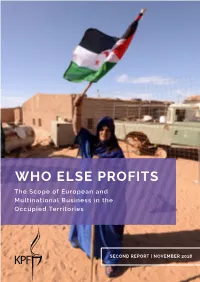

Who Else Profits the Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories

WHO ELSE PROFITS The Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories SECOND RepORT | NOVEMBER 2018 A Saharawi woman waving a Polisario-Saharawi flag at the Smara Saharawi refugee camp, near Western Sahara’s border. Photo credit: FAROUK BATICHE/AFP/Getty Images WHO ELse PROFIts The Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories This report is based on publicly available information, from news media, NGOs, national governments and corporate statements. Though we have taken efforts to verify the accuracy of the information, we are not responsible for, and cannot vouch, for the accuracy of the sources cited here. Nothing in this report should be construed as expressing a legal opinion about the actions of any company. Nor should it be construed as endorsing or opposing any of the corporate activities discussed herein. ISBN 978-965-7674-58-1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 WORLD MAp 7 WesteRN SAHARA 9 The Coca-Cola Company 13 Norges Bank 15 Priceline Group 18 TripAdvisor 19 Thyssenkrupp 21 Enel Group 23 INWI 25 Zain Group 26 Caterpillar 27 Biwater 28 Binter 29 Bombardier 31 Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. 33 Western Union 35 Transavia Airlines C.V. 37 Atlas Copco 39 Royal Dutch Shell 40 Italgen 41 Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica 43 NAgoRNO-KARABAKH 45 Caterpillar 48 Airbnb 49 FLSmidth 50 AraratBank 51 Ameriabank 53 ArmSwissBank CJSC 55 Artsakh HEK 57 Ardshinbank 58 Tashir Group 59 NoRTHERN CYPRUs 61 Priceline Group 65 Zurich Insurance 66 Danske Bank 67 TNT Express 68 Ford Motor Company 69 BNP Paribas SA 70 Adana Çimento 72 RE/MAX 73 Telia Company 75 Robert Bosch GmbH 77 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION On March 24, 2016, the UN General Assembly Human Rights Council (UNHRC), at its 31st session, adopted resolution 31/36, which instructed the High Commissioner for human rights to prepare a “database” of certain business enterprises1. -

Liste Des Participants 26-27.11.07

Nom Fonction Pays/institution 1 Mme LEVESQUE Michèle Ambassadeur Ambassade du Canada 2 Mr. BEKIC Darko Ambassadeur Ambassade de Croatie 3 Mr. RYTOVUORI Antti Ambassadeur Ambassade de la Finlande 4 Mr. PAP Laszlo Csaba Ambassadeur Ambassade de Hongrie 5 Mr. TOKOVININE Alexandre Ambassadeur Ambassade de Russie 6 Mr. ILICAK Haluk Ambassadeur Ambassade de Turquie 7 Mr. CLAVIER Frederic Deuxième conseiller Ambassade de France 8 Mr. FARHAT Bahroun Ministre conseiller Ambassade de Tunisie 9 Mr. BELHARIZI El Hadj Ministre Plénipotentiaire Ambassade de l’Algérie 10 Mr. MIHALACHE Catalin Constantin Attaché Militaire, Naval et de l’Air Ambassade de Roumanie 11 Mr. BRAHAM Mahmoud Conseiller Ambassade de l’Algérie 12 Mr. EVRARD Antoine Conseiller Ambassade de Belgique 13 Mr. MARCELLO Mori Conseiller Délégation de la Commission Européenne au Maroc 14 Mme SCHOUW Anne Conseiller Ambassade de Danemark 15 Mr. MARTIN YAGÜE José Luis Conseiller Politique Ambassade d’Espagne 16 Mme. ARI Nilgün Conseiller Ambassade de Turquie 17 Mr. MARIN Nicolae 1er Conseiller Ambassade de Roumanie 18 Mr. DAHROUG Tarek 1er Secrétaire Ambassade d’Egypte 19 Mr. ROMSLOE Borge Olav Premier Secrétaire Ambassade de Norvège 20 Mr. ARI Türker 1er Secrétaire Ambassade de Turquie 21 Mr. OREKHOV Nikolay 1er Secrétaire Ambassade de Russie 22 Melle KOELBEL Andrea Attaché de la Section Politique Ambassade de l’Allemagne 23 Mme Maria WOJTKIEWICZ Fonctionnaire Ambassade de Pologne 24 Mr. MELIANI Mohamed Doyen Faculté des Sciences Juridiques Economiques et Sociales Université Mohammed 1er Oujda 25 Mr. FARISSI Esserrhini Doyen Faculté des Sciences Juridiques Economiques et Sociales Université Mohammed Ben 26 Mr. BENHADDOU Abdeslam Doyen Faculté des Sciences Juridiques Economiques et Sociales Université Tanger 27 Mr. -

ARRETES Cdvm

Arrêté du ministre des finances et des investissements n° 2893-94 du 18 joumada I 1415 (24 octobre 1994) fixant la liste des journaux d'annonces légales prévue à l’article 39 du dahir portant loi n° 1-93-212 du 4 rabii II 1414 (21 septembre 1993) relatif au Conseil Déontologique des Valeurs Mobilières et aux informations exigées des personnes morales faisant appel public à l’épargne. (Modifié et complété par les arrêtés 1178-96 /1547-98 /939-99 /1142-00 / 1433-01 / 1601-01 / 872-02 /1288-02/2605-10/560-11/1930-11) Le ministre des finances et des investissements. Vu le dahir portant loi n° 1-93 212 du 4 rabii II 1414 (21 septembre 1993) relatif au conseil déontologique des valeurs mobilières et aux informations exigées des personnes morales faisant appel public à l'épargne, notamment son article 39, Arrête : Article premier : La liste des journaux d'annonces légales prévue à l'article 39 du dahir portant loi susvisé n° 1-93-212 du 4 rabii II 1414 (21 septembre 1993) est la suivante : 1. Al-Alam ; 2. Al-Bayane ; 3. Al-Ittihad Al-Ichtiraki ; 4. Al-Magrhib ; 5. Al-Rissalat Al-Ouma ; 6. Bayane Al-Youm ; 7. La Vie économique ; 8. L'Economiste ; 9. Le Matin du Sahara et du Maghreb ; 10. Libération ; 11. L'Opinion. 12. La Nouvelle Tribune 13. La Gazette du Maroc 14. Le journal 15. Finances News 16. Le Reporter 17. Le Quotidien du Maroc 18. Maroc hebdo International 19. La vérité 20. Rissalat al oumma 21. Aujourd’hui le Maroc 22. -

Système National D'intégrité

Parlement Exécutif Justice Les piliersduSystèmenationald’intégrité Administration Institutions chargées d’assurer le respect de la loi Système national d’intégrité Étude surle Commissions de contrôle des élections Médiateur Les juridictions financières Autorités de lutte contre la corruption Partis politiques Médias Maroc 2014 Maroc Société civile Entreprises ÉTUDE SUR LE SYSTÈME NATIONAL D’INTÉGRITÉ MAROC 2014 Transparency International est la principale organisation de la société civile qui se consacre à la lutte contre la corruption au niveau mondial. Grâce à plus de 90 chapitres à travers le monde et un secrétariat international à Berlin, TI sensibilise l’opinion publique aux effets dévastateurs de la corruption et travaille de concert avec des partenaires au sein du gouvernement, des entreprises et de la société civile afin de développer et mettre en œuvre des mesures efficaces pour lutter contre ce phénomène. Cette publication a été réalisée avec l’aide de l’Union européenne. Le contenu de cette publication relève de la seule responsabilité de TI- Transparency Maroc et ne peut en aucun cas être considéré comme reflétant la position de l’Union européenne. www.transparencymaroc.ma ISBN: 978-9954-28-949-5 Dépôt légal : 2014 MO 3858 © Juillet 2014 Transparency Maroc. Tous droits réservés. Photo de couverture: Transparency Maroc Toute notre attention a été portée afin de vérifier l’exactitude des informations et hypothèses figurant dans ce -rap port. A notre connaissance, toutes ces informations étaient correctes en juillet 2014. Toutefois, Transparency Maroc ne peut garantir l’exactitude et le caractère exhaustif des informations figurantdans ce rapport. 4 REMERCIEMENTS L’Association Marocaine de Lutte contre la Corruption -Transparency Maroc- (TM) remercie tout ministère, institution, parti, syndicat, ONG et toutes les personnes, en particulier les membres de la commission consultative, le comité de pilotage et les réviseurs de TI pour les informations, avis et participations constructives qui ont permis de réaliser ce travail. -

Demobilization in Morocco: the Case of the February 20 Movement by © 2018 Sammy Zeyad Badran

Demobilization in Morocco: The Case of The February 20 Movement By © 2018 Sammy Zeyad Badran Submitted to the graduate degree program in Political Science and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chairperson: Dr. Hannah E. Britton Co-Chairperson: Dr. Gail Buttorff Dr. Gary M. Reich Dr. Nazli Avdan Dr. Alesha E. Doan Date Defended: 31 May 2018 ii The dissertation committee for Sammy Zeyad Badran certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Demobilization in Morocco: The Case of The February 20 Movement Chairperson: Dr. Hannah E. Britton Co-Chairperson: Dr. Gail Buttorff Date Approved: 31 May 2018 iii Abstract This dissertation aims to understand why protests lessen when they do by investigating how and why social movements demobilize. I do this by questioning the causal link between consistent state polices (concessions or repression) and social movement demobilization. My interviews with the February 20 Movement, the main organizer of mass protests in Morocco during the Arab Spring, reveals how ideological differences between leftist and Islamist participants led to the group’s eventual halt of protests. During my fieldwork, I conducted 46 semi-structured elite interviews with civil society activists, political party leaders, MPs, and independent activists throughout Morocco. My interviews demonstrate that the February 20 Movement was initially united, but that this incrementally changed following the King’s mixed-policy of concessions and repression. The King’s concessionary policies convinced society that demands were being met and therefore led to the perception that the February 20 Movement was no longer needed, while repression highlighted internal divides.