How Good Is Your Chess? Wolfgang Unzicker Died on 20 April 2006, at the Age of 80. He Was the Leading Player in Post-War Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Column and CC News

1.e4 d5 2.e5 e6 3.d4 Nc6 4.Nf3 Bb4+ 5.c3 Be7 6.g3 Bd7 7.Bd3 ½–½ Counted among the mysteries that I just do not understand... PHILIDOR’S DEFENSE (C41) White: Matthew Ross (800) Black: Paul Rellias The Check Is in the Mail IECG 2005 DECEMBER 2006 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 f6 4. Bc4 Ne7 5. This month I honor a 25-year old dxe5 fxe5 6. 00 Bg4 7. Nxe5 Rg8 8. tradition of featuring miniature games in Bxg8 h6 9. Bf7 mate “The Check”. You may find it surprising that miniature games can Sometimes postal chess is an easy game happen to all ranks of chess players. – you just follow book for 10 to 15 They do, and here is the proof. The moves or so, and when your opponent February issue of Chess Life will also thinks for himself, you’ve got ‘em! contain some of these snowflakes, little wonders of nature. SICILIAN DEFENSE (B99) White: Olita Rause (2720) There are more tactics in this mini than Black: Vladimir Hefka (2574) you will find in three regular-sized 18th World Championship, 2003 games. 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 RUY LOPEZ (C70) 5.Nc3 a6 6.Bg5 e6 7.f4 Be7 8.Qf3 Qc7 White: Nowden 9.0–0–0 Nbd7 10.g4 b5 11.Bxf6 Nxf6 Black: Kristensen 12.g5 Nd7 13.f5 Nc5 14.f6 gxf6 15.gxf6 Correspondence 1933 Bf8 16.Rg1 h5 17.a3 Bd7 18.Kb1 Bc6 19.Bh3 Qb7 20.b4 1-0 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Bc5 5.c3 b5 6.Bc2 d5 7.d4 exd4 8.cxd4 Bb6 9.0–0 Bg4 10.exd5 Qxd5 11.Be4 Qd7 12.Qe1 0–0–0 13.Bxc6 Qxc6 14.Ne5 XABCDEFGHY Qe6 15.Qe4 c6 16.Qxg4 f5 17.Qxg7 8 +-+- ( Bxd4 18.Bf4 Bxb2 19.Nc3 Bxa1 20.Qa7 1–0 7++-++-' 6+-+& Two amateurs distill the essence of the 5+-+-+% Grandmaster draw. -

Opening Moves - Player Facts

DVD Chess Rules Chess puzzles Classic games Extras - Opening moves - Player facts General Rules The aim in the game of chess is to win by trapping your opponent's king. White always moves first and players take turns moving one game piece at a time. Movement is required every turn. Each type of piece has its own method of movement. A piece may be moved to another position or may capture an opponent's piece. This is done by landing on the appropriate square with the moving piece and removing the defending piece from play. With the exception of the knight, a piece may not move over or through any of the other pieces. When the board is set up it should be positioned so that the letters A-H face both players. When setting up, make sure that the white queen is positioned on a light square and the black queen is situated on a dark square. The two armies should be mirror images of one another. Pawn Movement Each player has eight pawns. They are the least powerful piece on the chess board, but may become equal to the most powerful. Pawns always move straight ahead unless they are capturing another piece. Generally pawns move only one square at a time. The exception is the first time a pawn is moved, it may move forward two squares as long as there are no obstructing pieces. A pawn cannot capture a piece directly in front of him but only one at a forward angle. When a pawn captures another piece the pawn takes that piece’s place on the board, and the captured piece is removed from play If a pawn gets all the way across the board to the opponent’s edge, it is promoted. -

From Los Angeles to Reykjavik

FROM LOS ANGELES CHAPTER 5: TO REYKJAVIK 1963 – 68 In July 1963 Fridrik Ólafsson seized a against Reshevsky in round 10 Fridrik ticipation in a top tournament abroad, Fridrik spent most of the nice opportunity to take part in the admits that he “played some excellent which occured January 1969 in the “First Piatigorsky Cup” tournament in games in this tournament”. Dutch village Wijk aan Zee. five years from 1963 to Los Angeles, a world class event and 1968 in his home town the strongest one in the United States For his 1976 book Fridrik picked only Meanwhile from 1964 the new bian- Reykjavik, with law studies since New York 1927. The new World this one game from the Los Angeles nual Reykjavik chess international gave Champion Tigran Petrosian was a main tournament. We add a few more from valuable playing practice to both their and his family as the main attraction, and all the other seven this special event. For his birthday own chess hero and to the second best priorities. In 1964 his grandmasters had also participated at greetings to Fridrik in “Skák” 2005 Jan home players, plus provided contin- countrymen fortunately the Candidates tournament level. They Timman showed the game against Pal ued attention to chess when Fridrik Benkö from round 6. We will also have Ólafsson competed on home ground started the new biannual gathered in the exclusive Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles for a complete a look at some critical games which against some famous foreign players. international tournament double round event of 14 rounds. -

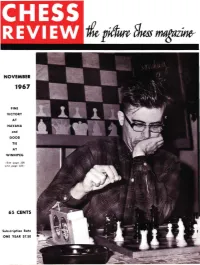

CR1967 11.Pdf

NOVEMBER 1967 FINE VICTORY AT HAVANA and GOOD TIE AT WINNIPEG ( Set PllO" ) 2$ .:ond pig" 323) 65 CENTS Subscription Rat. ONE YEAR 57.50 e wn 789 7 'h by 9 Inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 idea Yariations 1704 practical yariations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all yariations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A . HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr. Max Euwe. Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch. and many other noted authorities This latest Hild immense work, the most exhaustive of its kind, ex· plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not left hanging in mid.position with the query: What happens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. First come the moves with footnotes leading to the key positi on. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low pertinent observations, illustrated by " Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print, Practical and Supplementary Va riations, well annotated, exemplify the spaciolls paging and all the effective po::isibilities. Each line is appraised: +. - or =. The hi rge format- 71f2 x 9 inches-is designed for ease of read· other appurtenances of exqllis ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuIIling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal Jines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation-identify. ing diagrams are olher plus features. chess books! In addition to all else. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

A Game of Queens

Judit Polgar Teaches Chess 3 A Game of Queens by Judit Polgar with invaluable help from Mihail Marin Quality Chess www.qualitychess.co.uk Contents Key to Symbols used 4 Preface 5 1 Kasparov 11 2 Karpov 45 3 Korchnoi 71 4 The Rapid Match with Anand 101 5 Oliver 115 6 Hanna 141 7 The Opening 167 8 The Middlegame 199 9 The Endgame 217 10 Unexpected Moves 273 11 Official Competitions 285 12 Where It All Started 365 Records and Results 382 Name Index 384 Game Index 387 126 A Game of Queens Judit Polgar – Ivan Sokolov have relied, though, on the fact that I had never before faced it in practice. Wijk aan Zee 2005 13.d5 1.e4 e5 2.¤f3 ¤c6 3.¥b5 a6 4.¥a4 ¤f6 It looks logical to block the centre after Black 5.0–0 ¥e7 6.¦e1 b5 7.¥b3 d6 8.c3 0–0 no longer has the freeing ...c7-c6. In the long Ivan has played the Ruy Lopez throughout run, Black will have to re-develop his bishop, his career, so he has had the time to try out most likely with ...¥c8-d7. all kinds of systems: the Berlin Wall and the Marshall Attack, the Open and Bird If White wishes to maintain the tension in the variations, as well as several systems in the centre, the alternatives are 13.¤f1 ¦e8 14.¤g3 closed variations. and 13.b3. Back in 1994 in Madrid, I won my first game against Ivan by somewhat restricting his 13...g6 choice with 9.d4, but by 2005 I used to stick 13...c4 is a typical reaction after d4-d5, but to the main lines. -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

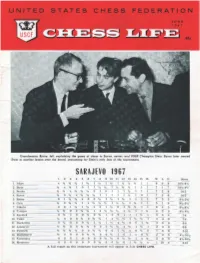

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

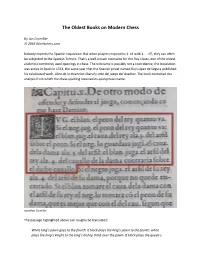

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess By Jon Crumiller © 2016 Worldchess.com Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition. But when players respond to 1. e4 with 1. … e5, they can often be subjected to the Spanish Torture. That’s a well-known nickname for the Ruy López, one of the oldest and most commonly used openings in chess. The nickname is possibly not a coincidence; the Inquisition was active in Spain in 1561, the same year that the Spanish priest named Ruy López de Segura published his celebrated work, Libro de la Invencion liberal y Arte del juego del Axedrez. The book contained the analysis from which the chess opening received its eponymous name. Jonathan Crumiller The passage highlighted above can roughly be translated: White king’s pawn goes to the fourth. If black plays the king’s pawn to the fourth: white plays the king’s knight to the king’s bishop third, over the pawn. If black plays the queen’s knight to queen’s bishop third: white plays the king’s bishop to the fourth square of the contrary queen’s knight, opposed to that knight. Or in our modern chess language: 1. e4, e5 2. Nf3, Nc6 3. Bb5. Jonathan Crumiller On the right is how the Ruy López opening would have looked four centuries ago with a standard chess set and board in Spain. This Spanish chess set is one of my oldest complete sets (along with a companion wooden set of the same era). Jonathan Crumiller Here is the Ruy López as seen with that companion set displayed on a Spanish chessboard, also from the 1600’s. -

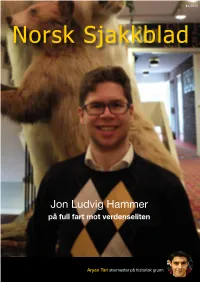

Norsk Sjakkblad

#4/2015 Norsk Sjakkblad Jon Ludvig Hammer på full fart mot verdenseliten Aryan Tari stormester på historisk grunn Sjakksett i topp- klasse til god pris: ENDA Klassisk Staunton Mahogny de luxe 55 mm En fin utgave av det BEDRE de store spiller med! SJAKK! Kr 1270 Vi har alltid gode sjakk- Endelig en ny og sterk nok produkter til deg selv og sjakkcomputer andre! Kanskje hente (rating ca 2000): gleder og fagimpulser fra en ny bok, eller en CHESS GENIUS Kr 1330 klassiker? Et sjakksett til glede for både øyne og hender? En lærerik DVD? Rykende ferske Fritz 15? Førsteklasses fersk repertoarbok for Et bra reisesjakkspill, en svart mot Spansk: skikkelig sjakk-klokke, Bologan’s Ruy Lopez Kr 300 eller en sjakkcomputer? La deg trygt friste i Ny og litt revo- Sjakkbutikken.no. lusjonerende treningspart- Vi har det største utvalget ner: Skyhøy i Norden med 3500 spillestyrke og forskjellige produkter, og 2 mill. partier vi kan gjerne gi deg FRITZ 15 gode råd! Her ser du Kr 690 noen av høstens aktuelle nyheter, som du kan lese mer om i nettbutikken. NB: Klubber i NSF og USF har 10% rabatt på sjakkmateriell ved Eller kom innom alle samlede kjøp minst kr 2000 og får ekstra gode tilbud på i Drammen! større kjøp. Og alltid gunstige bokpremiepakker til turneringer! Se også tilbud på www.sjakk.no Butikk: Hauges gate 84A, 3019 Drammen. Tlf. 32 82 10 64. Mandag – fredag kl 10 – 1630, torsdag til kl 1830. Epost: [email protected] Nr. 4/2015. 81. årgang. Norsk Sjakkblad et medlemsblad for Norges Sjakkforbund Faste spalter Artikler www.sjakk.no 04 LEDER 06 EM FOR LANDSLAG PÅ Redaktør Redaksjonen har ordet. -

The Modernized Ruy Lopez

The Modernized Ruy Lopez Volume 2 A Complete Repertoire for White First edition 2021 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2021 Dariusz Świercz All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. All sales or enquiries should be directed to Thinkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. Email: [email protected] Website: www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor: Romain Edouard Assistant Editor: Daniël Vanheirzeele Typesetting: Mark Haast Proofreading: Bob Holliman Software: Hub van de Laar Cover Design: Iwan Kerkhof Graphic Artist: Philippe Tonnard Production: BESTinGraphics ISBN: 9789464201086 D/2021/13730/6 The Modernized Ruy Lopez Volume 2 A Complete Repertoire for White Dariusz Świercz Thinkers Publishing 2021 I dedicate this book to my lovely wife Keyla, with whom I share my life and who loves me and supports me every day, my parents, Mamuś Ela and Tati Jurek, without whom I would have never achieved anything, my sister Ola, BIL Wit, Otylia and Marek, who root for me in every game I play, my R.I.P grandma Irena, who always believed in me, my R.I.P grandpa Rysiek, who taught me the game of chess. I wanted to say thank you and I love you! Key to Symbols ! a good move ? a weak move !! an excellent move ?? a blunder !? an interesting move ?! a dubious move □ only move N novelty ⟳ lead in development ⨀ zugzwang = equality ∞ unclear position © with compensation for the sacrificed material ⩲ White stands slightly better ⩱ Black stands slightly better ± White has a serious advantage ∓ Black has a serious advantage +- White has a decisive advantage -+ Black has a decisive advantage → with an attack ↑ with initiative ⇆ with counterplay ∆ with the idea of ⌓ better is ≤ worse is + check # mate Table of Contents Key to Symbols .................................................................................................... -

Chess-Moves-July-Aug

July / August 2006 NEWSLETTER OF THE ENGLISH CHESS FEDERATION £1.50 Magnificent Bequest to the British Chess Federation John Robinson the well known and much esteemed chess organiser and arbiter died on 1st February 2006. John dedicated much of his life to chess in many forms, now comes the news of a magnificent bequest to the British Chess Federation of the order of £650,000. Of this sum about £120,000 will be invested in the British Chess Federation Permanent Invested Fund enabling John’s expressed wish of support for the British Championship to be carried out, the remainder of the bequest will be invested in the John Robinson Youth Chess Trust a Charitable Trust which means no inheritance tax is payable on John’s bequest. It is proposed that this money should be invested in such a way that the capital may be retained and the accumulated income used for grants from the Trust. This Legacy provides stability for the future of the Championship and for Junior Chess. If anyone wishes to consider a bequest to ECF/BCF please contact the Office for further details. Editorial The establishment of the National Chess Library is progressing well. The rooms have now been cleared and the specialised ECF News shelving is in place. The books are in the process of being unpacked with book plates Nominations for being added. As soon as an opening date is fixed this will be announced. There are many Election at the ECF AGM other exciting projects, other than books The voluntary posts to be elected at being discussed with Hastings University, 0YD no later than 13.30 on Wednesday it is amazing how one venture can lead to the AGM on 1 October 006 are: 13 September 2006.