Deliverable D1.1 Report on Trust in Government, Politics, Policy and Regulatory Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

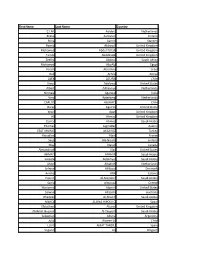

C.I.M. Aalders Netherlands Riikka Aaltonen Finland Riina Aarnio

C.I.M. Aalders Netherlands Riikka Aaltonen Finland Riina Aarnio Sweden Hamid Abboudi United Kingdom Mohamed Abdel-fattah United Kingdom Tamer Abdelrazik United Kingdom Zeelha Abdool South Africa Mohamed AboAly Egypt Yoram Abramov Israel Bob Achila Kenya ALEX ACUÑA Chile Sébastien Adamski Switzerland Amos Adelowo United States Albert Adriaanse Netherlands Nirmala Agarwal India Vera Agterberg Netherlands CARLOS AGUAYO Chile VIVIAN Aguilar United States Oscar Aguirre United States Wael Agur United Kingdom Ali Ahmad United Kingdom Gamal Ahmed Saudi Arabia Thomas Aigmüller Austria ESAT MURAT AKCAYOZ Turkey Riouallon Alain France Seija Ala-Nissilä Finland May Alarab Canada Alexandriah Alas United States AHMED ALBADR Saudi Arabia Lateefa Aldakhyel Saudi Arabia Akeel Alhafidh Netherlands Jassim Al-Hijji Kuwait Selwan Al-Kozai Denmark Annika Allik Estonia Hazem Al-Mandeel Saudi Arabia Sania Almousa Greece Marianna Alperin United States Salwan Al-Salihi Australia Ghadeer Al-Shaikh Saudi Arabia Efstathios Altanis United Kingdom Abdulah Hussein Al-Tayyem Saudi Arabia Sebastian Altuna Argentina Julio Alvarez U. Chile LLUIS AMAT TARDIU Spain Alicia Rita Amato Argentina Segaert An Belgium Lea Laird Andersen Denmark Vasanth Andrews United Kingdom MIHAELA CRISTINA ANTON Romania Beata Antosiak Poland Vanessa Apfel Brazil Catherine Appleby United Kingdom Rogério Araujo Brazil CARLOS ALFONSO ARAUJO ZEMBORAIN Argentina Rajka Argirovic Serbia Edwin Arnold New Zealand Christina Arocker Austria Juan Carlos Arone Chile Makiya Ashraf United Kingdom Kari Askestad -

Alumni @ Large

Colby Magazine Volume 99 Issue 1 Spring 2010 Article 10 April 2010 Alumni @ Large Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Recommended Citation (2010) "Alumni @ Large," Colby Magazine: Vol. 99 : Iss. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol99/iss1/10 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. ALUMNI AT LARGE 1920s-30s 1943 Meg Bernier Boyd Meg Bernier Boyd Colby College [email protected] Office of Alumni Relations Colby’s Oldest Living Alum: Waterville, ME 04901 1944 Leonette Wishard ’23 Josephine Pitts McAlary 1940 [email protected] Ernest C. Marriner Jr. Christmas did bring some communiqués [email protected] from classmates. Nathan Johnson wrote that his mother, Louise Callahan Johnson, 1941 moved to South San Francisco to an assisted Meg Bernier Boyd living community, where she gets out to the [email protected] senior center frequently and spends the John Hawes Sr., 92, lives near his son’s weekends with him. Her son’s e-mail address family in Sacramento, Calif. He enjoys eating is [email protected]. He is happy to be meals with a fellow World War II veterans her secretary. Y Betty Wood Reed lives and going to happy hour on Fridays. He has in Montpelier, Vt., in assisted living. She encountered some health problems but is is in her fourth year of dialysis and doing plugging along and looking forward to 2010! quite well. -

Tilburg University a Pastoral Psychology of Lament Blaine

Tilburg University A pastoral psychology of lament Blaine-Wallace, W. Publication date: 2009 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Blaine-Wallace, W. (2009). A pastoral psychology of lament. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. okt. 2021 A Pastoral Psychology of Lament A PASTORAL PSYCHOLOGY OF LAMENT Pastoral Method-Priestly Act-Prophetic Witness Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Tilburg, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op maandag 15 juni 2009 om 14.15 uur door William Blaine-Wallace geboren op 22 mei 1951 te Salisbury, North Carolina, USA 2 A Pastoral Psychology of Lament Promotores Prof. -

An Earthly Cosmology

Forum on Religion and Ecology Indigenous Traditions and Ecology Annotated Bibliography Abram, David. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York and Canada: Vintage Books, 2011. As the climate veers toward catastrophe, the innumerable losses cascading through the biosphere make vividly evident the need for a metamorphosis in our relation to the living land. For too long we’ve ignored the wild intelligence of our bodies, taking our primary truths from technologies that hold the living world at a distance. Abram’s writing subverts this distance, drawing readers ever closer to their animal senses in order to explore, from within, the elemental kinship between the human body and the breathing Earth. The shape-shifting of ravens, the erotic nature of gravity, the eloquence of thunder, the pleasures of being edible: all have their place in this book. --------. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. New York: Vintage, 1997. Abram argues that “we are human only in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human” (p. ix). He supports this premise with empirical information, sensorial experience, philosophical reflection, and the theoretical discipline of phenomenology and draws on Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of perception as reciprocal exchange in order to illuminate the sensuous nature of language. Additionally, he explores how Western civilization has lost this perception and provides examples of cultures in which the “landscape of language” has not been forgotten. The environmental crisis is central to Abram’s purpose and despite his critique of the consequences of a written culture, he maintains the importance of literacy and encourages the release of its true potency. -

AFI PREVIEW Check for Updates

THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE Oct. 29-Dec. 30, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 14 AFIPREVIEW European Union Film Showcase Oct 29-Nov 7 Plus: HEARTS AND MINDS EASY RIDER THE BIG RED ONE HEAVEN’S GATE George Stevens Centennial 50th Anniversary! Also: New Films from the Czech Republic, Tribute to Elia Kazan, ON THE WATERFRONT New 35mm Restoration Yuletide Classics, Washington Jewish Film Festival Much More! NOW PLAYING FEATURED FILMS Features 30th Anniversary! “HEARTS AND New Academy-Restored 2 HEARTS AND MINDS, Restored MINDS is not only 35mm Print! the best documentary 2EASY RIDER Academy Award-Winning 3 THE BIG RED ONE, Restored Documentary! I have ever seen, 3 ON THE WATERFRONT, 50th it may be the best Anniversary Restoration HEARTS AND MINDS movie ever... a film Film Festivals Opens Friday, October 22 that remains every bit “The ultimate victory will depend on the hearts and as relevant today. 4 EU SHOWCASE Required viewing for 13 Washington Jewish Film Festival: minds of the people.”—Lyndon Baines Johnson. Four films plus THE DIARY OF ANNE Documentarian Peter Davis (THE SELLING OF THE anyone who says, FRANK (p.11) PENTAGON) combined newsreel clips, TV reports, and ‘I am an American.’” striking color footage shot here and in a still war-torn —MICHAEL MOORE Film Series Vietnam, eschewing narration to let raw footage paint (2004) its own vivid portrait of the South and North 7 George Stevens Centennial Vietnamese, the Americans engineering the war here and abroad—and its critics. The 11 New from the Czech Republic -

First Name Last Name Country C.I.M. Aalders Netherlands Riikka

First Name Last Name Country C.I.M. Aalders Netherlands Riikka Aaltonen Finland Riina Aarnio Sweden Hamid Abboudi United Kingdom Mohamed Abdel-fattah United Kingdom Tamer Abdelrazik United Kingdom Zeelha Abdool South Africa Mohamed AboAly Egypt Yoram Abramov Israel Bob Achila Kenya ALEX ACUÑA Chile Amos Adelowo United States Albert Adriaanse Netherlands Nirmala Agarwal India Vera Agterberg Netherlands CARLOS AGUAYO Chile Oscar Aguirre United States Wael Agur United Kingdom Ali Ahmad United Kingdom Gamal Ahmed Saudi Arabia Thomas Aigmüller Austria ESAT MURAT AKCAYOZ Turkey Riouallon Alain France Seija Ala-Nissilä Finland May Alarab Canada Alexandriah Alas United States AHMED ALBADR Saudi Arabia Lateefa Aldakhyel Saudi Arabia Akeel Alhafidh Netherlands Selwan Al-Kozai Denmark Annika Allik Estonia Hazem Al-Mandeel Saudi Arabia Sania Almousa Greece Marianna Alperin United States Salwan Al-Salihi Australia Ghadeer Al-Shaikh Saudi Arabia MERCE ALSINA HIPOLITO Spain Efstathios Altanis United Kingdom Abdulah Hussein Al-Tayyem Saudi Arabia Sebastian Altuna Argentina Julio Alvarez U. Chile LLUIS AMAT TARDIU Spain Segaert An Belgium Lea Laird Andersen Denmark Vasanth Andrews United Kingdom Beata Antosiak Poland Vanessa Apfel Brazil Catherine Appleby United Kingdom Rogério Araujo Brazil CARLOS ALFONSO ARAUJO ZEMBORAIN Argentina Rajka Argirovic Serbia Edwin Arnold New Zealand Christina Arocker Austria Juan Carlos Arone Chile Makiya Ashraf United Kingdom Kari Askestad Norway R Phil Assassa United Kingdom LESTER ASTUDILLO Chile Leyla Atay Denmark STAVROS -

Feature Guide

FEATURE GUIDE Issue 20 autumn/winter 2021 difficult and expensive it is to try to do this by yourself, which is the concept behind the magazine: it allows artists to share space in the publication and reach our database of art gallery curators and directors. It’s a great way of capturing the attention of industry leaders; similar to exhibiting your work at an art fair where the visitors are directors and curators of the UK’s top galleries. It would be impossible to get all of these people in one room for obvious reasons, so the magazine is a great way of showcasing your work through the platform of a publication. Inside Artists covers a broad spectrum of the art world. • Exclusive interviews with artists. • Curated profiles of talented emerging and established artists. • Previews of upcoming events & exhibitions. Mission Statement We believe art to be one of the most important parts of humanity and culture. About Us It inspires, guides and challenges us, making people and society better and happier. Art should be accessible for everyone, as well as the opportunity to Inside Artists is a national contemporary arts and culture magazine, experience viewing work directly from the artist’s perspective. showcasing talented emerging and established artists to industry leaders and art lovers alike. Copies are sent out to over 600 of the UKs top galleries and Our publication encourages the contemporary arts by connecting artists, agencies, directly to curators and directors. Digital copies are also sent to galleries and exhibitions to industry leaders and art lovers alike. curators and directors at over 400 galleries across selected European cities and over 600 USA galleries. -

Beyond Boston

“Sitting in my offi ce with a partner from one of “I always got the mes- Boston’s prominent law sage that the reputation fi rms, I heard laughter we wanted was for doing come rippling along the absolutely fi rst-quality corridor and through the legal work. open door. “That isn’t to say we “My companion noticed haven’t been near other it. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘my matters. Don Hurley was partners and our juniors absolutely instrumental in often speak of how fre- getting the Massachusetts quently they hear laughter “I think anybody in the Business Development here in your offi ce.’ fi rm ought to stop and Corporation started. “He went on to say he think why you’re here, That was a very important thought it was a splen- and why is it a good legislative step. Charlie did thing, and I agreed. “I’m on the Hiring Post was instrumental in Committee. I enjoy it. thing to be practicing at Happiness in the day’s Goodwin Procter? What the fashioning of tax work is an essential ingre- The reason I enjoy it is legislation. that basically I like the are you looking for? “As far as new associates dient of any organization “Of course you want “But they were always place, not just because not are concerned, my advice that aspires to excellence.” to make money. But functioning as lobby- I’m a partner but because not is, ‘Don’t be intimidated.’ what do you want ists, as offi ceholders, it’s a very friendly place. -

Alumni at Large

Colby Magazine Volume 90 Issue 2 Spring 2001 Article 13 April 2001 Alumni at Large Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Recommended Citation (2001) "Alumni at Large," Colby Magazine: Vol. 90 : Iss. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol90/iss2/13 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. '20s/'30s-1940�1umni at large NEWSMAKERS kept them from joining us, and now 1940s Correspondents they're awaiting the birth of a first The Portland, Maine, Kiwanis honored Edward S. Boulos Jr. '39 on great-grandchild.... John and I thor 1940 Ernest C. Marriner Jr. November 14, 2000, with the club's 2000 Distinguished Service Award. A oughly enjoyed our trip to Provence 10 Walnut Drive but didn't get to hike as much as lifetime member of Disabled American Veterans, Boulos has served as Augusta, ME 04330-6032 expected. Highlights were the town director of Catl10lic Charities of Maine and on tl1e United Fund Construc [email protected] tion Division, the Greater Portland Development Com!1Ussion and other ofTourettes, the Canyon ofVerdun, a cooking class and several memo 1941 boards and committees primarily involved with Mercy Hospital. rable meals. L1 the spring we'll be Bonnie Roberts Hathaway 400 Atlantic Avenue #34C visiting Spain, followed by a week MILESTONES Leominster, MA 01453 with a son in Germany .... I wish 978-343-4259 more of you would send me news. -

1999 Newsletter the University of Texas at Austin Department of Geological Sciences Mark Cloos, Chairman Department of Geological Sciences

1999 Newsletter The University of Texas at Austin Department of Geological Sciences Mark Cloos, Chairman Department of Geological Sciences William L. Fisher, Director Geology Foundation Mary Koch Managing Editor Margaret L. Evans Layout and Design Photos by Joseph Jaworski No State-appropriated funds were used to publish this newsletter. This Page: Old fence showing cedar posts exhumed by Hurricane Carla waves at Gulf Beach, Port Aransas, September 1961, after burial by dunes for unknown period of time but possibly 60 to 70 years. There was no trace of wire or staples on the fence posts. Photo provided by Ernest L. Lundelius. 1999 Newsletter The University of Texas at Austin Department of Geological Sciences Cover: See related story inside. (1). An aerial tramway takes workers from the mill area at a 10,000-foot elevation to the Ertsberg office complex 2 3 next to the Ertsberg pit at 12,000 feet. Photo provided by 1 4 Mark Cloos. (2). Roy Luck (right) leads field trip in 1998 for PT Freeport Indonesia geologists at the Lime Quarry, the site of some of his M.S. thesis work. Photo provided by 7 55 Mark Cloos. (3). View looking south near the top of the Heavy Equipment Access Trail (HEAT Road) at 13,000-foot elevation with Ridge Camp barracks and workshops in the distance at 7,000-foot elevation. This road provides 8 6 direct vehicle access to the Grasberg Mine. Benyamin Sapiie mapped every structural feature along this winding road as part of his dissertation studies. Photo provided by Mark Cloos. (4). -

Final Program 8Th European Congress on Violence in Clinical Psychiatry “New Horizons in Interdisciplinary Approaches”

Final Program 8th European Congress on Violence in Clinical Psychiatry “New horizons in interdisciplinary approaches” Wednesday 23 October 2013 09.00 – 18.00 Registration Room Baekeland 1 Baekeland 3 10.00 – 13.30 Pre-Congress Pre-Congress Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Dr. Frans Fluttert Dr. Michiel de Vries Robbé (Netherlands): & Dr. Vivienne de Vogel The black box of (Netherlands): aggression unravelled: The Assessment of protective application of the Early factors for violence risk: Recognition Method The SAPROF 13.30 – 14.30 Lunch on one’s own Room Baekeland 1 Baekeland 3 14.30 – 18.00 Pre-Congress Pre-Congress Workshop 3 Workshop 4 Mr David Jones (UK): Dr. H.P.B. Lodewijks Violence in the workplace: (Netherlands): An endemic but not an Improvement of risk inevitable problem of 21st assessment and risk century healthcare delivery management in violent youth using the SAVRY Thursday 24 October 2013 08.00 – 18.00 Registration 08.00 – 09.00 Setting up Poster Display and Exhibition 09.00 – 18.00 Poster Display and Exhibition Room Auditorium 09.00 – 09.45 Opening & Welcome by Henk Nijman, Tom Palmstierna, Roger Almvik & Bart Thomas (chairs) Jo Vandeurzen, Vlaams Minister van Welzijn, Volksgezondheid en Gezin Prof.Dr. Eric Mortier, afgevaardigd bestuurder UZ Gent Country flag parade by Nico Oud (Organiser) 09.45 – 10.30 Keynote 1: Risk Assessment of Spousal Violence: What approach should we use? Prof. Henrik Belfrage (Sweden) Chair: Tom Palmstierna 10.30 – 11.00 Keynote 2: Assaulting behaviour: a personal story about the violence no one should experience at work Ms. Kelly Mclean (USA) Chair: Tom Palmstierna 11.00 – 11.30 Break 11.30 – 12.00 Keynote 3: Compulsive Care: Measures taken in regard to people who have been interned and others in need of care Mr. -

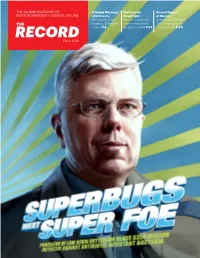

Record Fall 2016 Fall 2016 Inside the Record

THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF A Happy Marriage Fighting the Annual Report BOSTON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW of Interests Good Fight of Giving MIT and BU share Four BU Law alumni Building on Excellence: THE Intellectual Property share their passion The Campaign for BU clinics. P.8 for social justice. P.14 School of Law. P.54 RECORD FALL 2016 FALL 2016 INSIDE THE RECORD BU Law The alumni Maureen A. O’Rourke Dean, Professor of Law, receives grant magazine of Michaels Faculty to combat Boston Research Scholar antimicrobial University Oice of Development resistance School of Law & Alumni Relations Lillian Bicchieri, 2 Development Associate Thomas Damiani, Senior Sta A Happy Coordinator Marriage of Terry McManus, 8 Assistant Dean for Interests: Development & BU Law’s IP Alumni Relations Curriculum Oice of Communications & Marketing Ann Comer-Woods, Assistant Dean for Communications & Marketing Lauren Eckenroth, 12 Senior Writer Opportunity in Failure Contributors Rebecca Binder 14 (LAW’06) Patrick L. Kennedy (COM’04) Fighting the Meghan Laska Good Fight: Trevor Persaud (STH’18) Alumni in Indira Priyadarshini Public Service 20 (COM’16) The Right Sara Rimer to Innovate Corinne Steinbrenner (COM’06) Photography Josh Andrus Alex Boerner BU Photography School News John Gillooly & & Updates Professional Event Images, Inc. Max Hirshfeld Tim Llewellyn 22 Chris McIntosh Mark Ostow Photography Melissa Ostrow Class Notes & Jackie Ricciardi Chris Sorensen In Memoriam Michael D. Spencer Dan Watkins Design Ellie Steever, Boston University Creative Services Cover art and Tell us what you illustrations think! Complete our 54 The Red Dress Annual Report Owen Gildersleeves reader survey at of Giving Peter Hoey bit.ly/bulawrecord.