The Triumphant Progress of Market Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California State University, Northridge Exploitation

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE EXPLOITATION, WOMEN AND WARHOL A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Kathleen Frances Burke May 1986 The Thesis of Kathleen Frances Burke is approved: Louise Leyis, M.A. Dianne E. Irwin, Ph.D. r<Iary/ Kenan Ph.D. , Chair California State. University, Northridge ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Dr. Mary Kenon Breazeale, whose tireless efforts have brought it to fruition. She taught me to "see" and interpret art history in a different way, as a feminist, proving that women's perspectives need not always agree with more traditional views. In addition, I've learned that personal politics does not have to be sacrificed, or compartmentalized in my life, but that it can be joined with a professional career and scholarly discipline. My time as a graduate student with Dr. Breazeale has had a profound effect on my personal life and career, and will continue to do so whatever paths my life travels. For this I will always be grateful. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition, I would like to acknowledge the other members of my committee: Louise Lewis and Dr. Dianne Irwin. They provided extensive editorial comments which helped me to express my ideas more clearly and succinctly. I would like to thank the six branches of the Glendale iii Public Library and their staffs, in particular: Virginia Barbieri, Claire Crandall, Fleur Osmanson, Nora Goldsmith, Cynthia Carr and Joseph Fuchs. They provided me with materials and research assistance for this project. I would also like to thank the members of my family. -

Grade Four Session One – the Theme of Modernism

Grade Four Session One – The Theme of Modernism Fourth Grade Overview: In a departure from past years’ programs, the fourth grade program will examine works of art in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in preparation for and anticipation of a field trip in 5th grade to MoMA. The works chosen are among the most iconic in the collection and are part of the teaching tools employed by MoMA’s education department. Further information, ideas and teaching tips are available on MoMA’s website and we encourage you to explore the site yourself and incorporate additional information should you find it appropriate. http://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning! To begin the session, you may explain that the designation “Modern Art” came into existence after the invention of the camera nearly 200 years ago (officially 1839 – further information available at http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dagu/hd_dagu.htm). Artists no longer had to rely on their own hand (painting or drawing) to realistically depict the world around them, as the camera could mechanically reproduce what artists had been doing with pencils and paintbrushes for centuries. With the invention of the camera, artists were free to break from convention and academic tradition and explore different styles of painting, experimenting with color, shapes, textures and perspective. Thus MODERN ART was born. Grade Four Session One First image Henri Rousseau The Dream 1910 Oil on canvas 6’8 1/2” x 9’ 9 ½ inches Collection: Museum of Modern Art, New York (NOTE: DO NOT SHARE IMAGE TITLE YET) Project the image onto the SMARTboard. -

Art: Graphic Design and Illustration (ARTC) 1

Art: Graphic Design and Illustration (ARTC) 1 ARTC 165 Illustration ART: GRAPHIC DESIGN AND 3 Units (Degree Applicable, CSU) Lecture: 36 Lab: 71 ILLUSTRATION (ARTC) Prerequisite: ARTD 15A or ANIM 104 Corequisite: ARTD 20 or ARTD 21 or ARTD 17A or ANIM 101A (any of ARTC 100 Fundamentals of Graphic Design which may have been taken previously) 3 Units (Degree Applicable, CSU, C-ID #: ARTS 250) Lecture: 36 Lab: 71 Contemporary illustration with an emphasis on story, editorial, and Advisory: ARTD 15A and ARTD 20 advertising applications. Proper uses of illustrative rendering techniques in traditional drawing and painting media, paper, and their integration to Fundamentals of graphic design for the commercial art industry. electronic media. Using professional illustration software, peripherals, Technology, creativity, design, and production. Adobe Photoshop to and color laser printing, students advance to produce more complex produce effective commercial art. illustrations. ARTC 120 Print Design and Advertising ARTC 167 Visual Development 3 Units (Degree Applicable, CSU) 3 Units (Degree Applicable, CSU) Lecture: 36 Lab: 71 Lecture: 36 Lab: 71 Prerequisite: ARTC 100 Prerequisite: ARTC 163 or (ANIM 101A and ARTD 16) Corequisite: ARTD 20 (May be taken previously) Development of conceptual designs for illustration in video games, film, Theories, concepts, and skills for the design and layout of animation, and comic books, using composition, shape, value, and color printed commercial art. Covers typical printed products including as visual tools for storytelling. Students cannot receive credit for both advertisements, flyers, brochures, posters, books, and catalogs. Focuses ARTC 167 and ANIM 167. on using Adobe InDesign with additional exposure to Adobe Photoshop ARTC 169 Contemporary Illustration and Adobe Illustrator. -

Pop Artists Andy Warhol (1925 – 1987) Is the Standard Bearer of Pop Art and Now One of the Most Famous Artists in the World

Moxie University Shares: University Pop Artists Andy Warhol (1925 – 1987) is the standard bearer of Pop Art and now one of the most famous artists in the world. He was born to immigrant parents from Eastern Europe and was frail, solitary and unpopular as a child. He contracted scarlet fever and the subsequent complications kept him in bed for a lengthy time. While in bed he listened to the radio and collected pictures of movie stars. This experience would set his career-path. He would get a degree in commercial art and work in NY at commercial advertising agencies. His first “works” were whimsical illustrations of women’s fashion shoes, he seemed to give the shoes a unique personality of their own. In the early 60’s Warhol would start a revolution in art by depicting ordinary items of consumption as “Art.” This would become the catalyst for “pop” art. In general Warhol sought (By Jack Mitchell, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15047586) out the most ironic and cynical elements to satirize in American society. His works were his way of “thumbing his nose” at American Exceptionalism in an age when America was at its zenith in terms of global cultural power and influence. In the end he wanted to be a celebrity more than he wanted to be an artist, fame was its own-just- reward. He is also responsible for creating an industrial method of producing works with his “factory” process. Warhol’s later life could be thought of as the first instance of a Reality-TV-Show, just the act of living was an “Art” on its own. -

College Articulation Agreements Commercial Art & Advertising

College Articulation Agreements Commercial Art & Advertising Design CIP Code: 50.0402 Art Institute of Pittsburgh: • FNDA11O Observational Drawing (3 credits) • FNDA150 Digital Color Theory (3 credits) • GWDA101 Applications & Industry (3 credits) • PHOA101 Principles of Photography (3 credits) • FND135 Introduction to Web Design (3 credits) • FNDA105Design Fundamentals (3 credits) • FNDA135 Image Manipulation (3 credits) • G131 Typography (3 credits) Bucks County Community College: • VAFA160 – Introduction to Printmaking or VAFA 161 – Printmaking/Silkscreen (3 credits) • VAMM100 – Digital Imaging (3 credits) • VAGD999 – Graphic Design elective (3 credits) Harrisburg University Science & Technology • IMED 170, Visual Design Fundamentals (4 credits) Hussian College: • Eligible students shall receive up to 9 elective credit hours in a B.F.A in Specialized Technology degree program o FAD103 Fundamentals of 2D Design: Design Elements o GDD202 Graphic Design 1 o DMD202 Web Programming 1: Advanced Styling with CSS New and updated agreements will be added to this document on an on-going basis. In addition to agreements between MBIT and the post-secondary schools, agreements have been initiated state-wide through the Pennsylvania Department of Education SOAR (Students Occupationally and Academically Ready) Initiative. These agreements can be found online at www.collegetransfer.net and by searching PA Bureau of CTE SOAR Programs. Students are also eligible for three (3) college credits through the National College Credit Recommendation Service based on their NOCTI written score. Students must receive at least a 70% on the written component of the Commercial and Advertising Art PA NOCTI Post-Test to receive college credit. A list of cooperating colleges and universities can be found online at www.nationalccrs.org and by searching Colleges and Universities. -

GUIDE to MAJORS at YESHIVA: ART What Is the Art Major? What

GUIDE TO MAJORS AT YESHIVA: ART Choosing a major can be stressful, but it is important to understand that you can pursue almost any career regardless of which major you choose. While there are some exceptions, most entry-level positions simply require general transferable skills—those that can be learned in one setting and applied in another. Relevant experience through internships and activities is generally more important to employers than a major. It is best to choose an area that you find interesting and where you have the ability to do well. What is the Art Major? The Art department at Stern College for Women offers students an opportunity to develop a Shaped Major with a focus in either Art History (34 credits) or Studio Art (40-41 credits). Art History is the study of art from various periods, cultures, and parts of the world. It teaches students to interpret and understand works of art of many types, by learning about artists' lives and their societies. Studio Art aims to strengthen a student’s natural talent in either the fine arts or the various design fields by offering courses in painting, design, architecture, fashion, drawing, sculpture, or computer graphics. The student develops a Shaped Major based on her particular art interest. Students also may sign up for an 18-credit Art Minor. Furthermore, any Stern College student who wishes to explore her artistic side is welcome in classes. Majors may take up to ten credits at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), and minors may take five credits. What can I do with a Major in Art? Graduates with a focus on Art History can enter a wide range of professional careers including museums, galleries, auction houses, education, publishing and more. -

POP ART: FOCUS (Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, and Claes Oldenburg)

CHALLENGING TRADITION: POP ART: FOCUS (Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, and Claes Oldenburg) TITLE or DESIGNATION: Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? ARTIST: Richard Hamilton CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Pop Art DATE: 1956 C.E. MEDIUM: collage on paper ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthistory.kha nacademy.org/campbell s-soup-cans.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Campbell’s Soup Cans ARTIST: Andy Warhol CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Pop Art DATE: 1962 C.E. MEDIUM: synthetic polymer paint on 32 canvases ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthistory.khana cademy.org/pop-art.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Gold Marilyn Monroe ARTIST: Andy Warhol CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Pop Art DATE: 1962 C.E. MEDIUM: synthetic polymer paint, silkscreened, and oil on canvas ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/ artworks/warhol-marilyn- diptych-t03093/text- illustrated-companion TITLE or DESIGNATION: Marilyn Diptych ARTIST: Andy Warhol CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Pop Art DATE: 1962 C.E. MEDIUM: oil, acrylic, and silkscreen enamel on canvas ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://www.yale.edu/publicart/lipstick. html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks ARTIST: Claes Oldenburg CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Pop Art DATE: 1969-74 C.E. MEDIUM: weathering steel CHALLENGING TRADITION: POP ART: SELECTED TEXT (Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, and Claes Oldenburg) ANDY WARHOL and the POP ART MOVEMENT Online Links: Andy Warhol - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia YouTube - Andy Warhol Empire YouTube - andy warhol – sleep YouTube - andy warhol – kiss YouTube - Artist Spotlight: Andy Warhol Eats a Hamburger Pop art - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Kitsch - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Roy Lichtenstein - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Claes Oldenburg - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coosje van Bruggen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Richard Hamilton. -

How Does Contemporary Artists Consolidate Their Success And

Sotheby's Institute of Art Digital Commons @ SIA MA Theses Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2019 How does contemporary artists consolidate their success and achievements through social media platform such as Instagram? : Case study of successful co-existing relationship developed between contemporary artists Ai Weiwei and KAWS with their Instagram account Rouchen Yao Sotheby's Institute of Art Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses Part of the Arts Management Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, and the Technology and Innovation Commons Recommended Citation Yao, Rouchen, "How does contemporary artists consolidate their success and achievements through social media platform such as Instagram? : Case study of successful co-existing relationship developed between contemporary artists Ai Weiwei and KAWS with their Instagram account" (2019). MA Theses. 57. https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses/57 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Digital Commons @ SIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How does contemporary artists consolidate their success and achievements through social media platform such as Instagram? Case study of successful co-existing relationship developed between contemporary artists Ai Weiwei and KAWS with their Instagram account Ruochen Yao Word Count: 11311 Abstract In the following thesis, I would compare and contrast the two art world phenomenon:Ai Weiwei and KAWS, whom have very distinctive artistic focus and style. And how the two artists utilize their social media platform to achieve different purposes and reflect different values. -

Commercial Art: Doors of Success for an Artist

|| Volume 3 || Issue 5 || May 2018|| ISO 3297:2007 Certified ISSN (Online) 2456-3293 COMMERCIAL ART: DOORS OF SUCCESS FOR AN ARTIST Dr. Uzma Saeed Waseem Department of fine Arts, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, UP, India ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Abstract: The objective of commercial art is to encourage, clarify and educate architecture. Commercial art is an art of artistic services, which refers to art produced for marketing purposes, mainly ads. Generally, advertising art involves the creation of books, ads for different goods, signs, posters as well as other displays to encourage the selling or approval of items, services or ideas. We make art and express ourselves, and the most important of these days it has been considered a great career. The study shows that the young aspiring artist will take on an occupation and brighten up his life. Keywords: Commercial Art; Fine Art; Graphic Design; Artist; Employability -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- INTRODUCTION commercial art, all of which include the completion of a degree program in commercial art or a related field. Commercial art is artwork created for advertisement or By commercial art, we mean any creative work created in marketing purposes. Commercial artists produce art used to series and directed at the needs of the user. This is made of promote goods, such as commercials in newspapers, social rather heterogeneous techniques and materials, ranging from media, and other outlets. It is an art that is mass-produced and printing methods to digital ones. It reflects on the talent of its intended to sell items, to increase the popularity of goods, or creator in terms of his technological skills and involves words to express a particular message. -

Program Learning Outcomes

PROGRAM LEARNING OUTCOMES FOUNDATION The Foundation Program, for first-year students, provides core studies for life-long learning and professional practices in the visual arts by teaching fundamental skills that enable students to become adept, well- informed makers. The liberal arts curriculum informs students’ ability to construct meaning using the formal elements of art and design. PROGRAM LEARNING OUTCOMES Students in the Foundation Program will: • Acquire and apply Fundamental Skills, which include mindful making and improving of work by the manipulation of art and design media. • Demonstrate Critical Thinking Skills including the ability to distinguish between and use rational, intuitive, and critical thinking processes and to construct meaning using visual information. • Discern Visual Quality through identifying visual strengths and weaknesses to promote aesthetic resolution and clarity of intention. • Build Professionalism through strategies for success such as attentiveness, time management skills, and the ability to commit to a personal vision in the endeavor of art making. • Develop Quantitative Skills including the ability to use sound principles of proportion to measure, calculate, and transfer dimensions of the observed and built world. • Demonstrate Inventiveness and the Spirit of Investigation, utilizing visual and idea-oriented research, the spirit of play, and the sequential application of process to develop problem solving skills. • Develop an Awareness of Social Responsibility by working individually and collaboratively to consider the social and environmental impact of art and design. LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES Liberal Arts and Sciences provides students with a diverse and intellectually stimulating environment that cultivates critical tools, enabling students to become informed, creative artists and designers who are prepared to meet global challenges. -

Graphic Design Degree: Bachelor of Fine Arts in Graphic Design

Graphic Design Degree: Bachelor of Fine Arts in Graphic Design The Graphic Design program at Marietta College provides opportunities and presents challenges to prepare students for a career in commercial art and design. Advertising, marketing, promotions, print production, and business practices are all related fields that are covered in the curriculum. The core goal of the program is to train students to be effective vis- ual communicators and problem solvers in order to contribute their personal abilities to the professional marketplace. Students are trained in fundamental studio art mediums. Those skills are then translated to a digital workflow using industry standard equipment — Macintosh computers, and a host of contemporary tools housed in the Graphics Design Lab in the Hermann Fine Arts Center. While the Design Lab hosts the majority of classroom lectures, demonstrations, and student work area, additional classes in painting, printmaking, art history and research assignments take graphic design students across many disciplines to offer exposure to a variety of ideas and methods. Full-time faculty: Jolene Powell, Professor Sara Always-Rosenstock, Assistant Professor Abigail Spung, Lecturer Facilities: Mac-based computer lab Latest design software and professional-grade scanners Printmaking, painting, design, drawing, ceramics studios Large exhibition gallery To enrich your education as a designer, each major is required to take additional courses in marketing, public relations, business and Sample Courses: creative writing. -

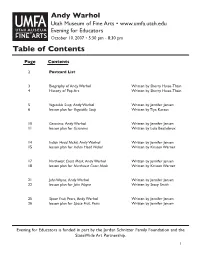

Table of Contents

Andy Warhol Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Evening for Educators October 10, 2007 • 5:30 pm - 8:30 pm Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Postcard List 3 Biography of Andy Warhol Written by Sherry Hsiao-Thain 4 History of Pop Art Written by Sherry Hsiao-Thain 5 Vegetable Soup, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 6 lesson plan for Vegetable Soup Written by Tiya Karaus 10 Geronimo, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 11 lesson plan for Geronimo Written by Lola Beatlebrox 14 Indian Head Nickel, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 15 lesson plan for Indian Head Nickel Written by Kristen Warner 17 Northwest Coast Mask, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 18 lesson plan for Northwest Coast Mask Written by Kristen Warner 21 John Wayne, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 22 lesson plan for John Wayne Written by Stacy Smith 25 Space Fruit, Pears, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 26 lesson plan for Space Fruit, Pears Written by Jennifer Jensen Evening for Educators is funded in part by the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation and the StateWide Art Partnership. 1 Andy Warhol Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Evening for Educators October 10, 2007 • 5:30 pm - 8:30 pm Postcard List 1. Andy Warhol Vegetable Soup Screenprint Purchased with funds from Mrs. Paul L. Wattis. Museum # 1986.021.002 ©2007 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / ARS, New York 2. Andy Warhol Geronimo, 1986 Screenprint Gift of Edith Carlson O’Rourke, Museum # 1996.48.1.10 ©2007 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / ARS, New York 3.