Botanical Illustrations Emily N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roozengaarde's Bulb Planting Guide

15867 Beaver Marsh Road Mount Vernon, WA 98273 Frequently 360-424-8531 or 866-4TULIPS Asked www.Tulips.com / [email protected] Questions WILL BULBS GROW ANYWHERE? Yes, bulbs will grow in many different climates. Warmer climates are more challenging and may require pre-cooling each fall prior to plant- ing. The year we ship your bulbs, we do any necessary pre-cooling here on our farm prior to shipment—your bulbs will be ready to plant when you receive them! DO BULBS NEED TO BE WATERED? Yes, if Mother Nature does not take care of it for you, then water during dry spells. Be sure not to oversoak the planting area. Water just enough so that it absorbs quickly. Water after planting, during growth, and even after topping if the soil is dry. WHAT IS THE BEST TYPE OF SOIL AND FERTILIZER? Soil needs to provide adequate drainage and oxygen for the bulbs. We recommend using a slow release fertilizer specifically designed for flower bulbs - usually a N - P - K formula. DO BULBS NEED TO BE DUG IN THE SUMMER? We recommend digging tulip bulbs each year after the foliage has died down naturally. They are more prone to disease and rot if left in the ground through the summer months. Other bulbs like daffodils can typically be dug on a 3-5 year schedule. If you experience diminished results in the spring, you should dig your bulbs that summer. WHAT IS THE BEST WAY TO STORE MY BULBS IF I DIG THEM? After digging, make sure to dry bulbs thoroughly. -

Bulb Dormancy in Vitro—Fritillaria Meleagris: Initiation, Release and Physiological Parameters

plants Review Bulb Dormancy In Vitro—Fritillaria meleagris: Initiation, Release and Physiological Parameters Marija Markovi´c*, Milana Trifunovi´cMomˇcilov , Branka Uzelac , Sladana¯ Jevremovi´c and Angelina Suboti´c Department of Plant Physiology, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stankovi´c“—NationalInstitute of the Republic of Serbia, University of Belgrade, Bulevar Despota Stefana 142, 11060 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] (M.T.M.); [email protected] (B.U.); [email protected] (S.J.); [email protected] (A.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In ornamental geophytes, conventional vegetative propagation is not economically feasible due to very slow development and ineffective methods. It can take several years until a new plant is formed and commercial profitability is achieved. Therefore, micropropagation techniques have been developed to increase the multiplication rate and thus shorten the multiplication and regeneration period. The majority of these techniques rely on the formation of new bulbs and their sprouting. Dormancy is one of the main limiting factors to speed up multiplication in vitro. Bulbous species have a period of bulb dormancy which enables them to survive unfavorable natural conditions. Bulbs grown in vitro also exhibit dormancy, which has to be overcome in order to allow sprouting of bulbs in the next vegetation period. During the period of dormancy, numerous physiological processes occur, many of which have not been elucidated yet. Understanding the process of dormancy will allow us to speed up and improve breeding of geophytes and thereby achieve economic profitability, which is very important for horticulture. This review focuses on recent findings in the area of Citation: Markovi´c,M.; Momˇcilov, bulb dormancy initiation and release in fritillaries, with particular emphasis on the effect of plant M.T.; Uzelac, B.; Jevremovi´c,S.; growth regulators and low-temperature pretreatment on dormancy release in relation to induction of Suboti´c,A. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a Reconstruction of the Clusius Garden

The Netherlandish humanist Carolus Clusius (Arras 1526- Leiden 1609) is one of the most important European the exotic botanists of the sixteenth century. He is the author of innovative, internationally famous botanical publications, the exotic worldof he introduced exotic plants such as the tulip and potato world of in the Low Countries, and he was advisor of princes and aristocrats in various European countries, professor and director of the Hortus botanicus in Leiden, and central figure in a vast European network of exchanges. Carolus On 4 April 2009 Leiden University, Leiden University Library, The Hortus botanicus and the Scaliger Institute 1526-1609 commemorate the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death with an exhibition The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a reconstruction of the Clusius Garden. Clusius carolus clusius scaliger instituut clusius all3.indd 1 16-03-2009 10:38:21 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:11 Pagina 1 Kleine publicaties van de Leidse Universiteitsbibliotheek Nr. 80 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 2 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 3 The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius (1526-1609) Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009 Edited by Kasper van Ommen With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LEIDEN 2009 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 4 ISSN 0921-9293, volume 80 This publication was made possible through generous grants from the Clusiusstichting, Clusius Project, Hortus botanicus and The Scaliger Institute, Leiden. Web version: https://disc.leidenuniv.nl/view/exh.jsp?id=exhubl002 Cover: Jacob de Monte (attributed), Portrait of Carolus Clusius at the age of 59. -

Thermonastic TROPISM

THERMOnastic TROPISM Eleni Katrini | Ruchie Kothari | Mugdha Mokashi Bio_Logic Lab School of Architecture, Carnegie Mellon University ABSTRACT Motivation: To develop dynamic elements which respond to changes in temperature Approach: The thermonastic movements of the Tulip flower were looked at for inspiration to develop conceptual systems based on movement and heat. The tulip flower opens and closes its petals based on the external temperature. The petals open up when the temperature is high and close when the temperature is low. This movement of the petals is facilitated by movement of water through the plant. Experiments were conducted using paper which is a fibrous material exhibiting properties similar to that of a flower petal. Water at different temperatures was studied as a conducting medium. Findings: Based on analysis, different forms of flowers were created. This includes flowers with varying surface areas, flowers made using composite materials, laminated and chiseled flowers, flowers with varying edge exposure etc. The study was focused on exploring the effects of capillary action on fibrous materials. The observations were focused on- - Range of movement of petals - Duration for capillary action - Effect of hot and cold temperature It was seen that the range of movement was the same for most of the prototypes. All the flowers other than the flowers for which the range of movement was restricted opened up to 180o. The time taken for the water to rise depended on the density and the surface area of the paper in contact with the water. Increase in density of the paper in contact with water, increases the time taken for the water to rise up. -

Tyler Schmidt, Plant Science Major, Department of Horticultural Science

Interspecific Breeding for Warm-Winter Tolerance in Tulipa gesneriana L. Tyler Schmidt, Plant Science Major, Department oF Horticultural Science 19 December 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Focus on breeding of Tulipa gesneriana has largely concentrated on appearance. Through interspecific breeding with more warm-tolerant species, tolerance of warm winters could be introduced into the species, decreasing dormancy requirements and expanding the range of tulips southward. Additionally, long-lasting foliage can be favored in breeding to allow plants to store more energy for daughter bulbs. Continued virus and fungal resistance breeding will decrease infection. Primary benefits are for gardeners and landscapers who, under the current planting schedule, are planting tulip bulbs annually, wasting money. Producers benefit from this by reducing cooling times, saving energy, greenhouse space, and tulip bulbs lost to diseases in coolers. UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA AQUAPONICS: REPORT TITLE 1 I. INTRODUCTION A. Study species Tulips (Tulip gesneriana L.) are one of the most historically significant and well-known horticultural crops in the world. Since entering Europe via Constantinople in the mid-sixteenth century, the Dutch tulip market became one of the first “economic bubbles” of modern civilization, creating and destroying fortunes in four brief years (Lesnaw and Ghabrial, 2000). Since this time, tulips have remained extremely popular as more improved cultivars are released. However, a problem remains: even though viral resistance and long-lasting cultivars are introduced, few are capable of surviving in a climate with truly mild winters and only select cultivars are able to store enough energy for another year of flowering, even in climates with colder winters. Current planting schemes suggest planting annually, wasting tulip bulbs (Dickey, 1954). -

Liliaceae Lily Family

Liliaceae lily family While there is much compelling evidence available to divide this polyphyletic family into as many as 25 families, the older classification sensu Cronquist is retained here. Page | 1222 Many are familiar as garden ornamentals and food plants such as onion, garlic, tulip and lily. The flowers are showy and mostly regular, three-merous and with a superior ovary. Key to genera A. Leaves mostly basal. B B. Flowers orange; 8–11cm long. Hemerocallis bb. Flowers not orange, much smaller. C C. Flowers solitary. Erythronium cc. Flowers several to many. D D. Leaves linear, or, absent at flowering time. E E. Flowers in an umbel, terminal, numerous; leaves Allium absent. ee. Flowers in an open cluster, or dense raceme. F F. Leaves with white stripe on midrib; flowers Ornithogalum white, 2–8 on long peduncles. ff. Leaves green; flowers greenish, in dense Triantha racemes on very short peduncles. dd. Leaves oval to elliptic, present at flowering. G G. Flowers in an umbel, 3–6, yellow. Clintonia gg. Flowers in a one-sided raceme, white. Convallaria aa. Leaves mostly cauline. H H. Leaves in one or more whorls. I I. Leaves in numerous whorls; flowers >4cm in diameter. Lilium ii. Leaves in 1–2 whorls; flowers much smaller. J J. Leaves 3 in a single whorl; flowers white or purple. Trillium jj. Leaves in 2 whorls, or 5–9 leaves; flowers yellow, small. Medeola hh. Leaves alternate. K K. Flowers numerous in a terminal inflorescence. L L. Plants delicate, glabrous; leaves 1–2 petiolate. Maianthemum ll. Plant coarse, robust; stems pubescent; leaves many, clasping Veratrum stem. -

This Illustration Provided for the Journal's Cover

Banisteria, Number 24, 2004 © 2004 by the Virginia Natural History Society The Earliest Illustrations and Descriptions of the Cardinal David W. Johnston 5219 Concordia Street Fairfax, Virginia 22032 ABSTRACT In the 16th century Northern Cardinals were trapped in Mexico, then sent as caged birds because of their beauty and song to various places in Europe and south Africa. The Italian, Aldrovandi, obtained a caged bird in Italy and with a woodcut, published the first known illustration of a cardinal in 1599. The great English naturalist, Francis Willughby, in conjunction with John Ray, published a painting of a cardinal in 1678, and the eccentric and prolific collector, James Petiver, included an illustrated caged cardinal from south Africa in his monumental Opera (1767). Mark Catesby was the first artist to paint a cardinal (probably in Virginia) with a natural background (c. 1731). Aldrovandi's woodcut and description in 1599 represent the earliest known mention of the Northern Cardinal. Key words: Cardinalis cardinalis, history, illustrations, Northern Cardinal. To an ornithological historian it is exciting and Grosbeak from the Indies.” This woodcut was the first rewarding to be able to trace the earliest report and published image of the species (Simpson, 1985). illustration of any bird. Such has been the case for the bird A translation of Aldrovandi’s Latin description reads: now called the Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). In the 16th century the cardinal was a favorite cage bird “A bird of this sort, pictured in the guise of life, was among Europeans, long before it was reported by English sent to me several days ago on the command of his serene colonists in its North American range. -

Carl Linnaeus's Botanical Paper Slips (1767–1773)

Intellectual History Review ISSN: 1749-6977 (Print) 1749-6985 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rihr20 Carl Linnaeus's botanical paper slips (1767–1773) Isabelle Charmantier & Staffan Müller-Wille To cite this article: Isabelle Charmantier & Staffan Müller-Wille (2014) Carl Linnaeus's botanical paper slips (1767–1773), Intellectual History Review, 24:2, 215-238, DOI: 10.1080/17496977.2014.914643 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17496977.2014.914643 © 2014 The Author(s). Published by Taylor & Francis. Published online: 02 Jun 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2111 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 6 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rihr20 Intellectual History Review, 2014 Vol. 24, No. 2, 215–238, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17496977.2014.914643 Carl Linnaeus’s botanical paper slips (1767–1773) Isabelle Charmantier and Staffan Müller-Wille Department of History, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK* The development of paper-based information technologies in the early modern period is a field of enquiry that has lately benefited from extensive studies by intellectual historians and historians of science.1 How scholars coped with ever-increasing amounts of empirical knowledge presented in print and manuscript – leading to the so-called early modern “information overload”–is now being increasingly analysed and understood.2 In this paper we will turn to an example at the close of the early modern period. Towards the very end of his academic career, the Swedish nat- uralist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) – best known today for his “sexual” system of plant classifi- cation and his binomial nomenclature – used little paper slips of a standard size to process information on plants and animals that reached him on a daily basis. -

General Introduction

01hfdst.02-055 09-07-2002 12:31 Pagina 9 Chapter 1 General introduction Flower bulbs are a major export product of the Netherlands. In 2001, the Netherlands produced an estimated number of 10 billion flower bulbs, which is 65% of the total world production.Tulip, narcissus and lilies are the most important crops. More than half of the flower bulbs is used for the forcing market for cut flowers and pot plants and the rest for the dry sales market for parks and home gardens. More than 75% of the total Dutch production is exported to the United States, Japan and to countries within the European Union. (Sources: Internationaal Bloembollen Centrum, Productschap Tuinbouw) 9 01hfdst.02-055 09-07-2002 12:31 Pagina 10 Chapter 1 Flower bulbs Periodicity of flower bulbs Under natural circumstances, flower bulbs are exposed to seasonal changes in temperature, rainfall and light (Le Nard and De Hertogh, 1993a).The growth cycle of the bulbs is adapted to that periodicity. Depending on the season of flowering, growth activity of the bulbs takes place during spring or autumn. Spring flowering bulbs have a rest period during the summer and resume growth during autumn (Le Nard and De Hertogh, 1993a). They require a warm-cold-warm temperature sequence for growth and development.Typical examples are the tulip, freesia, narcissus and hyacinth. Summer flowering bulbs rest in winter and resume growth in spring. Typical examples of summer flowering bulbs are lily, allium and gladiolus. The time of flowering is not related to the time of flower initiation. Flower initiation can take place during different periods of the year and at different stages of bulb development. -

Spring Flowering Bulbs for Kentucky Gardens

HortFacts 52-04 SPRING FLOWERING BULBS FOR KENTUCKY GARDENS Robert G. Anderson, Extension Specialist in Floriculture Spring flowering bulbs are an important part of the landscape in Kentucky. Crocus and daffodils tell us that spring is on its way and red tulips are a Derby Day tradition. These flowers are recognized by most people but there are many other spring flowering bulbs that can be used around your home. Hundreds of different kinds of flower bulbs are available for fall planting. You may obtain them from mail order bulb companies, garden centers, supermarkets or department stores. Some are familiar and others have long, hard-to-pronounce names. Generally, spring flowering bulbs do very well the first spring after they are planted. Yet, many home gardeners want the bulbs to come back year after year or naturalize in their home landscape. Continuing trials at the UK College of Agriculture's Arboretum and Horticulture Research Farm have focused on the naturalization of spring flowering bulbs. Bulbs planted in various sites and given different types of care have been observed through four spring flowering seasons. The following list of recommended bulbs for Kentucky landscapes is based on these trials. Planting Site Well-drained sites are essential. Established gardens and Wind Flower – ‘Radar’ beds or newly cultivated areas are fine. The soil pH should be 6.0 to 7.0. Bulbs will not do well in heavy clay soils, so poor soils should be amended with compost, peat moss or other organic matter. Most bulbs prefer a site that does not receive full sunlight in the middle of the day. -

The Science of Spring-Flowering Bulbs

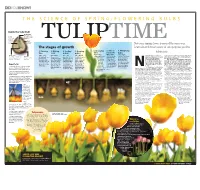

THE SCIENCE OF SPRING-FLOWERING BULBS Inside the tulip bulb Flower bud In the center of Scales the bulb is a baby Thick, fleshy flower bud. leaves are arranged Tunic TULIPTIME around the Paper outer stem covering Not every spring flower is created the same way. The stages of growth Learn about the root causes of our gorgeous gardens 1. Planting 2. Making 3. Cooling 4. Growing 5. Blooming 6. Time to 7. Multiplying By Christine Facciolo time roots period period time regenerate bulbs Special to The News Journal April - May May - June July - Sept. Basal stem Sept. - Oct. November Dec. - Jan. Feb. - March othing announces the arrival of fleshy scales from drying out. Imbricate bulbs like the As the tulips bloom After the bloom- Up to five small bulbs The compressed stem con- Roots The tulip bulbs are The roots start Now starts the rest The bulbs begin to spring better than a flower garden lily do not have this protective covering and must be they receive ing period, the can be expected to nects the flower, scales Grow out of the planted. Most growing out of the period. In order for change as the full of colorful and fragrant kept moist prior to planting. basal stem their nourish- flowers are cut grow out of the and roots of the plant important: plant base. They establish the bulbs to bloom starch, or carbohy- blooms. The plants that grace Like the bulb, a seed is a miniature plant with a ment from and the leaves are mother bulb. They these gardens come from either protective cover and a food supply called endosperm.