The Inner Game of Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dvoretsky Lessons 48

The Instructor The Effects of Replaying I have frequently mentioned, in books and articles, an effective training method: replaying specially selected positions – positions which cannot be “resolved” from beginning to end, so there is really no sense in trying. Instead, players must find, in succession, a series of correct decisions independently (or nearly independently) of each other. In the majority of such exercises, play continues for a minimum of ten moves, although sometimes longer. After all, a shorter variant could in fact be calculated from beginning to end, which would then abolish it as a playing exercise. But The there are sometimes exceptions. The brilliant attack from the following game, which remained hidden in the Instructor annotations, and which is now offered for your consideration, has for some reason never become widely known, although its basic ideas were demonstrated Mark Dvoretsky in Mikhail Botvinnik’s annotations from his book 1941 Match-Tournament. But even those who are familiar with Botvinnik’s analysis will be none the worse for it – for they too will see sharp new variations. Botvinnik - Bondarevsky Leningrad/Moscow 1941 So – you have White. Try to find each move in turn, taking Black’s replies from the following text. Or you might play out this fragment against a friend: he will also find it a problem requiring deep insight into the position. 39.Ne2xd4! In combination with White’s next move, this is a rather obvious exchange: in this way, White gets the opportunity to speculate on the pin along the a1-h8 diagonal. In the game, Botvinnik played the much weaker 39.Ng3?, and after 39...Qe6! 40.Re2 Be3, he ought to have been dead lost: White has neither his pawn, nor any sort of compensation for it. -

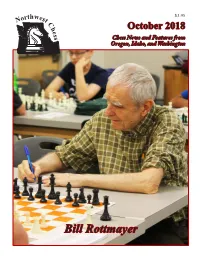

Bill Rottmayer on the Front Cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the Oldest Participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open

$3.95 orthwes N t C h October 2018 e s s Chess News and Features from Oregon, Idaho, and Washington Bill Rottmayer On the front cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the oldest participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open. Bill has participated in most Spokane Chess Club events the last few years. Photo credit: James Stripes. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. On the back cover: POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Dustin Herker at the Las Vegas International Festival where Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. he won first place U1000. Photo credit: Nancy Keller. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: NWC Staff Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, Editor: Jeffrey Roland, of West Linn, Oregon. [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Publisher: Duane Polich, Submissions [email protected] Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content [email protected] are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are Board Representatives subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: David Yoshinaga, Josh Sinanan, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Jeffrey Roland, Adam Porth, Chouchanik Airapetian, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Brian Berger, Duane Polich, Alex Machin, Eric Holcomb. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2018 by Northwest Chess. -

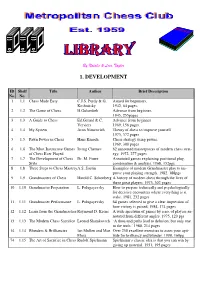

1. Development

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

Chess for Dummies‰

01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page iii Chess FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION by James Eade 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page ii 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page i Chess FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page ii 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page iii Chess FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION by James Eade 01_584049 ffirs.qxd 7/29/05 9:19 PM Page iv Chess For Dummies®, 2nd Edition Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2005 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permit- ted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317-572-3447, fax 317-572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Livros De Xadrez

LIVROS DE XADREZ No. TÍTULO Autor Editora 1 100 Endgames You Must Know Jesus de la Villa New In Chess 2 Ajedrez - La Lucha por la Iniciativa Orestes Aldama Zambrano Paidotribo 3 Alexander Alekhine Alexander Kotov R.H.M. Press 4 Alexander Alekhine´s Best Games Alexander Alekhine Batsford Chess 5 Analysing the Endgame John Speelman Batsford Chess 6 Art of Chess Combination Znosko-Borovsky Dover 7 Attack and Defence M.Dvoretsky & A.Yusupov Batsford Chess 8 Attack and Defence in Modern Chess Tactics Ludek Pachman RPK 9 Attacking Technique Colin Crouch Batsford Chess 10 Better Chess for Average Players Tim Harding Dover 11 Bishop v/s Knight: The Veredict Steve Mayer Ice 12 Bobby Fischer My 60 Memorable Games Bobby Fischer Faber & Faber Limited 13 Bobby Fischer Rediscovered Andrew Soltis Batsford 14 Bobby Fischer: His Aproach to Chess Elie Agur Cadogan 15 Botvinnik - One Hundred Selected Games M.Botvinnik Dover 16 Building Up Your Chess Lev Alburt Circ 17 Capablanca Edward Winter McFarland 18 Chess Endgame Quis Larry Evans Cardoza Publishing 19 Chess Endings Yuri Averbach Everyman Chess 20 Chess Exam and Training Guide Igor Khmelnitsky I am Coach Press 21 Chess Middlegames Yuri Averbach Cadogan Chess 22 Chess Praxis Aron Nimzowitsch Hays Publishing 23 Chess Praxis Aron Nimzowitsch Hays Publishing 24 Chess Self-Improvement Zenon Franco Gambit 25 Chess Strategy for the Tournament Player Alburt & Palatnik Circ 26 Creative Chess Amatzia Avni Cadogan Chess 27 Creative Chess Opening Preparation Viacheslav Eingorn Gambit 28 Endgame Magic J.Beasley -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

The Old Indian Move by Move

Junior Tay The Old Indian move by move www.everymanchess.com About the Author is a FIDE Candidate Master and an ICCF Senior International Master. He is a for- Junior Tay mer National Rapid Chess Champion and represented Singapore in the 1995 Asian Team Championship. A frequent opening surveys contributor to New in Chess Yearbook, he lives in Balestier, Singapore with his wife, WFM Yip Fong Ling, and their dog, Scottie. He used the Old Indian Defence exclusively against 1 d4 in the 2014 SportsAccord World Mind Games Online event, which he finished in third place out of more than 3000 participants. Also by the Author: The Benko Gambit: Move by Move Ivanchuk: Move by Move Contents About the author 3 Series Foreword 5 Bibliography 6 Introduction 7 1 The Classical Tension Tussle 17 2 Sämisch-Style Set-Ups and Early d4-d5 Systems 139 3 Various Ideas in the Fianchetto System 274 4 Marshalling an Attack with 4 Íg5 and 5 e3 395 5 Navigating the Old Indian Trail: 20 Questions 456 Solutions 467 Index of Variations 490 Index of Games 495 Foreword Move by Move is a series of opening books which uses a question-and-answer format. One of our main aims of the series is to replicate – as much as possible – lessons between chess teachers and students. All the way through, readers will be challenged to answer searching questions and to complete exercises, to test their skills in chess openings and indeed in other key aspects of the game. It’s our firm belief that practising your skills like this is an excellent way to study chess openings, and to study chess in general. -

The Martian System in Chess, Part 1

THE MARTIAN SYSTEM IN CHESS This system is for beginners in chess, and if it is applied diligently in the games they play, they will soon be very much improved, and theirs will be the joy of beating those who once beat them. LESSON ONE, OBSERVING HIS THREATS By James Hurt June 16, 1938 Introduction These lessons are for beginners in chess. You have learned the moves of the different pieces, you know the laws of the game, you have played a few games, but, as yet, you are not a very good player. Chess has fascinated you because it is something new to you. However, if you continue to lose games you are going to lose interest in chess; chess will sour on you. Despite the romantic background of chess, and, in spite of chess being an ideal conflict of two minds, the real joy, the real satisfaction of chess, comes from winning games. I am going to teach you how to defeat your opponent in a new and easy way. I may not succeed in this, but if we work together I am sure that you will begin to win more and more of the games you play. I haven’t very much to tell you, but the things I do tell you must be over-learned. It would be foolish to read this over once, and then expect to find yourself a better player. You Must use the know1edge I give you in every game you play, and you must practice using the points in these lessons at every move. -

April 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 48, Number 2 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION April 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT COLORADO SCHOLASTIC ONLINE CHAMPIONSHIP Volume 48, Number 2 Colorado Chess Informant April 2021 From the Editor With measured steps, the Colorado chess scene may just be com- ing back to life. It has been announced that the Colorado Open has been sched- uled for Labor Day weekend this year - albeit with safety proto- cols in place. Be sure to check out the website as the date nears (www.ColoradoChess.com) because as we are aware, things The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a could change. The Denver Chess Club has also announced a Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- tournament in June of this year - go to their website tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are (www.DenverChess.com) for more information on that one. tax deductible. It is with a heavy heart and profound sadness that a friend and Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) ‘chess bud’ of mine has passed away. Not long after his 70th memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to birthday in January, Michael Wokurka collapsed at his home on additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- the 22nd - and never regained consciousness. No prior warning tic tournament membership is available for $3. or health issues were known. His obituary online is listed here: ● Send address changes to - Attn: Alexander Freeman to the https://tinyurl.com/2rz9zrca. He loved the game of chess, and email address [email protected]. -

Finding Checkmate in N Moves in Chess Using Backtracking And

Finding Checkmate in N moves in Chess using Backtracking and Depth Limited Search Algorithm Moch. Nafkhan Alzamzami 13518132 Informatics Engineering School of Electrical Engineering and Informatics Institute Technology of Bandung, Jalan Ganesha 10 Bandung [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—There have been many checkmate potentials that has pieces of a dark color. There are rules about how pieces players seem to miss. Players have been training for finding move, and about taking the opponent's pieces off the board. checkmates through chess checkmate puzzles. Such problems can The player with white pieces always makes the first move.[4] be solved using a simple depth-limited search and backtracking Because of this, White has a small advantage, and wins more algorithm with legal moves as the searching paths. often than Black in tournament games.[5][6] Keywords—chess; checkmate; depth-limited search; Chess is played on a square board divided into eight rows backtracking; graph; of squares called ranks and eight columns called files, with a dark square in each player's lower left corner.[8] This is I. INTRODUCTION altogether 64 squares. The colors of the squares are laid out in There have been many checkmate potentials that players a checker (chequer) pattern in light and dark squares. To make seem to miss. Players have been training for finding speaking and writing about chess easy, each square has a checkmates through chess checkmate puzzles. Such problems name. Each rank has a number from 1 to 8, and each file a can be solved using a simple depth-limited search and letter from a to h. -

Chess & Bridge

2013 Catalogue Chess & Bridge Plus Backgammon Poker and other traditional games cbcat2013_p02_contents_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:18 Page 1 Contents CONTENTS WAYS TO ORDER Chess Section Call our Order Line 3-9 Wooden Chess Sets 10-11 Wooden Chess Boards 020 7288 1305 or 12 Chess Boxes 13 Chess Tables 020 7486 7015 14-17 Wooden Chess Combinations 9.30am-6pm Monday - Saturday 18 Miscellaneous Sets 11am - 5pm Sundays 19 Decorative & Themed Chess Sets 20-21 Travel Sets 22 Giant Chess Sets Shop online 23-25 Chess Clocks www.chess.co.uk/shop 26-28 Plastic Chess Sets & Combinations or 29 Demonstration Chess Boards www.bridgeshop.com 30-31 Stationery, Medals & Trophies 32 Chess T-Shirts 33-37 Chess DVDs Post the order form to: 38-39 Chess Software: Playing Programs 40 Chess Software: ChessBase 12` Chess & Bridge 41-43 Chess Software: Fritz Media System 44 Baker Street 44-45 Chess Software: from Chess Assistant 46 Recommendations for Junior Players London, W1U 7RT 47 Subscribe to Chess Magazine 48-49 Order Form 50 Subscribe to BRIDGE Magazine REASONS TO SHOP ONLINE 51 Recommendations for Junior Players - New items added each and every week 52-55 Chess Computers - Many more items online 56-60 Bargain Chess Books 61-66 Chess Books - Larger and alternative images for most items - Full descriptions of each item Bridge Section - Exclusive website offers on selected items 68 Bridge Tables & Cloths 69-70 Bridge Equipment - Pay securely via Debit/Credit Card or PayPal 71-72 Bridge Software: Playing Programs 73 Bridge Software: Instructional 74-77 Decorative Playing Cards 78-83 Gift Ideas & Bridge DVDs 84-86 Bargain Bridge Books 87 Recommended Bridge Books 88-89 Bridge Books by Subject 90-91 Backgammon 92 Go 93 Poker 94 Other Games 95 Website Information 96 Retail shop information page 2 TO ORDER 020 7288 1305 or 020 7486 7015 cbcat2013_p03to5_woodsets_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:53 Page 1 Wooden Chess Sets A LITTLE MORE INFORMATION ABOUT OUR CHESS SETS..