Department for International Development: Departmental Report 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reducing Reoffending: the “What Works” Debate

REDUCING REOFFENDING: THE “WHAT WORKS” DEBATE RESEARCH PAPER 12/71 22 November 2012 The remanding and sentencing of people alleged to have been involved in the riots in England in August 2011 caused the prison population to rise again, before falling back to pre-riot levels. It now stands at around 86,300 (below the record high of 88,179 on 2 December 2011). That surge in the prison population made the debate about prison and whether it “works” all the more urgent. Evidently, while they are in prison, offenders cannot commit further offences in the community, but what happens when they are released? Are they less likely to reoffend? Does prison help offenders to “go straight”? If not, what might? Is prison, in fact, an expensive way of making bad people worse? This paper examines the evidence for the effectiveness of prison and programmes in the community aimed at reducing reoffending and some of the claims and counter-claims for whether “prison works”. Gabrielle Garton Grimwood Gavin Berman Recent Research Papers 12/61 Growth and Infrastructure Bill [Bill 75 of 2012-13] 25.10.12 12/62 HGV Road User Levy Bill [Bill 77 of 2012-13] 29.10.12 12/63 Antarctic Bill [Bill 14 of 2012-13] 30.10.12 12/64 European Union (Croatian Accession and Irish Protocol) Bill [Bill 76 of 01.11.12 2012-13] 12/65 Trusts (Capital and Income) Bill [Bill 81 of 2012-13] 02.11.12 12/66 Scrap Metal Dealers Bill: Committee Stage Report 06.11.12 12/67 Economic Indicators, November 2012 06.11.12 12/68 Unemployment by Constituency, November 2012 14.11.12 12/69 US Elections 2012 16.11.12 12/70 Small Charitable Donations Bill: Committee Stage Report 20.11.12 Research Paper 12/71 Contributing Authors: Gabrielle Garton Grimwood, Home Affairs Section Gavin Berman, Social and General Statistics Section The authors are grateful to Professor Shadd Maruna (director of the Institute of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Queen’s University, Belfast) for his help with this paper. -

ON the PATH of RECOVERY TOP 100 COMPANIES > PAGE 6

CROATIA, KOSOVO, MACEDONIA, MOLDOVA, MOLDOVA, MACEDONIA, KOSOVO, CROATIA, MONTENEGRO, ROMANIA, SERBIA, SLOVENIA ALBANIA, BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, BULGARIA, BULGARIA, ALBANIA, BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, ON THE PATH ROMANIA’S BCR SHINES NO QUICK RECOVERY FOR OF RECOVERY AGAIN IN TOP 100 BANKS SEE INSURERS IN 2011 RANKING TOP 100 COMPANIES TOP 100 BANKS TOP 100 INSURERS > PAGE 6 > PAGE 22 > PAGE 30 interviews, analyses, features and expert commentsperspective for to anthe additional SEE market real-time coverage of business and financial news from SEE investment intelligence in key industries Real-time solutions for your business in Southeastast Europe The business news and analyses of SeeNews are also available on your Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters terminals. wire.seenews.com editorial This fi fth annual edition of SeeNews TOP 100 SEE has tried to build on the previous issues by off ering even richer content, more features, analyses and a variety of views on the economy of Southeast Europe (SEE) and the region’s major companies. We have prepared an entirely new ranking called TOP 100 listed companies, part of the TOP listed companies section, giving its rationale along with a feature story on the stock exchanges in the region. For the fi rst time we have included research on Turkey and Greece, setting the scene for companies from the two countries to enter the TOP 100 rankings in the future. The scope has been broadened with a chapter dedicated to culture and the leisure industry, called SEE colours, which brings the region into the wider context of united Europe. One of the highlights of the 2012 edition is a feature writ- ten by the President of the European Bank for Reconstruc- tion and Development, Sir Suma Chakrabarti. -

Private Sector for Food Security

PRIVATE SECTOR FOR FOOD SECURITY Speakers and moderators’ biographies SAIT HALIM PASHA MANSION, ISTANBUL - 13 SEPTEMBER 2012 PROMOTING PRIVATE AGRICULTURAL INVESTMENT AND TRADE FROM THE BLACK SEA TO THE MEDITERRANEAN Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations NOTES BIOS BIOS Lourdes Adriano Lead Agriculture Sector Specialist, Asian Development Bank Lourdes Adriano received her graduate and post graduate training in Development Economics and Agriculture Economics at the University of Cambridge, University of Sussex, and the University of the Philippines. Her technical and work experiences are in the fields of food security, agricultural, rural and regional development, agriculture trade, and poverty reduction. She has worked as a professor and as senior official and policy advisor to the Government of the Philippines, as well as authored articles and books on topics like market assisted land reform, sub-regional cooperation, and rural development. Since late 000, she has worked with the Asian Development Bank and is currently the Advisor concurrently Practice Leader (Agriculture, Food Security and Rural Development) and Unit Head of the Regional and Sustainable Development Department’s Agricultural, Rural Development and Food Security Unit. Sir Suma Chakrabarti President, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Sir Suma Chakrabarti, born in 959 in West Bengal, India, is the sixth President of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). The Bank’s Board of Governors elected Sir Suma as President of the EBRD for the next four years, from July 3, 0. He replaces Thomas Mirow, the President since 008. Sir Suma has extensive experience in international development economics and policy-making, as well as in designing and implementing wider public service reform. -

After the Berlin Wall a History of the EBRD Volume 1 Andrew Kilpatrick

After the Berlin Wall A History of the EBRD Volume 1 Andrew Kilpatrick After the Berlin Wall A History of the EBRD Volume 1 Andrew Kilpatrick Central European University Press Budapest–New York © European Bank for Reconstruction and Development One Exchange Square London EC2A 2JN United Kingdom Website: ebrd.com Published in 2020 by Central European University Press Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, Hungary Tel: +36-1-327-3138 or 327-3000 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ceupress.com 224 West 57th Street, New York NY 10019, USA This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Terms and names used in this report to refer to geographical or other territories, political and economic groupings and units, do not constitute and should not be construed as constituting an express or implied position, endorsement, acceptance or expression of opinion by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development or its members concerning the status of any country, territory, grouping and unit, or delimitation of its borders, or sovereignty. ISBN 978 963 386 394 7 (hardback) ISBN 978 963 386 384 8 (paperback) ISBN 978 963 386 385 5 (ebook) Library of Congress Control Number: 2020940681 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations VII Acknowledgments XI Personal Foreword by Suma Chakrabarti XV Preface 1 PART I Post-Cold War Pioneer 3 Chapter 1 A New International Development Institution 5 Chapter 2 Creating the EBRD’s DNA 43 Chapter 3 Difficult Early Years 73 Chapter 4 Restoring Credibility -

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons dated 6 July 2016 for The Report of the Iraq Inquiry Report of a Committee of Privy Counsellors Volume V Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 6 July 2016 HC 265-V 46561_17b Viking_Volume V Title Page.indd 1 17/06/2016 12:48 © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identifi ed any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] Print ISBN 9781474110136 Web ISBN 9781474110143 ID 23051601 46561 07/16 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fi bre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Offi ce 46561_17b Viking_Volume V Title Page.indd 2 17/06/2016 12:48 Volume V CONTENTS 5 Advice on the legal basis for military action, November 2002 to March 2003 1 6.1 Development of the military options for an invasion of Iraq 171 6.2 Military planning for the invasion, January to March 2003 385 46561_17b Viking_Volume V Title Page.indd 3 17/06/2016 12:48 46561_17b Viking_Volume V Title Page.indd 4 17/06/2016 12:48 SECTION 5 ADVICE ON THE LEGAL BASIS FOR MILITARY ACTION, NOVEMBER 2002 TO MARCH 2003 Contents Introduction and key findings .......................................................................................... -

The Politics of the Results Agenda in DFID 1997-2017

Report The politics of the results agenda in DFID 1997-2017 Craig Valters and Brendan Whitty September 2017 Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel: +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7922 0399 E-mail: [email protected] www.odi.org www.odi.org/facebook www.odi.org/twitter Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI publications for their own outputs, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of ODI. © Overseas Development Institute 2017. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). Cover photo: Paul Frederickson, ‘Big Ben’, 2017 Acknowledgements This research benefited from the support of a wide range of people, both within the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and in the course of collecting material for Brendan Whitty’s PhD. For the former, this research was supported by an internal Research and Innovation Fund. The latter was funded by the University of East Anglia, School of International Development. The authors are grateful for the extremely detailed and constructive peer reviews. These include formal peer reviews by Simon Maxwell, Cathy Shutt and Nilima Gulrajani. Gideon Rabinowitz contributed significantly to an early draft of this paper and provided useful comments on the final draft. Further reviews were provided by ODI colleagues, including David Booth, Freddie Carver, Helen Dempster, Joanna Rea, Mareike Schomerus and Leni Wild. -

Downloaded for Personal Non-Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Campbell, Elizabeth Margaret (2011) Scottish adult literacy and numeracy policy and practice: a social practice model: rhetoric or reality. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2948/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Scottish Adult Literacy and Numeracy Policy and Practice A Social Practice Model – Rhetoric or Reality? Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Faculty of Education University of Glasgow Elizabeth Campbell October 2010 Abstract This thesis is about the story of the development of Adult Literacy and Numeracy policy and practice in Scotland. It includes some of my personal experiences over the past thirty years working in the field of adult education and particularly in literacies. However, the focus is primarily on the years 2000 –2006 when major developments took place in this field of adult learning. One of the tenets of the „new literacies‟ policy and practice is that it is predicated on a social practice model. This thesis explores whether this assertion is rhetoric or reality. -

The Office of Lord Chancellor — Evidence

SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION The Office of Lord Chancellor Oral and written evidence Contents Sir Alex Allan KCB, Permanent Secretary, Department of Constitutional Affairs then Ministry of Justice, 2004-07, and Sir Thomas Legg KCB, Permanent Secretary of the Lord Chancellor’s Department, 1989-98 — Oral Evidence (QQ 63-75) .................................................................. 4 Dr Gabrielle Appleby, Deputy Director of the Public Law and Policy Research Unit, University Of Adelaide — Written evidence (OLC0018) ........................................................................... 17 Archives and Records Association — Written evidence (OLC0024) ........................................ 25 Association of Personal Injury Lawyers — Written evidence (OLC0015) ................................ 28 The Bar Council — Written evidence (OLC0026) ..................................................................... 31 Bindmans LLP — Written evidence (OLC0023) ........................................................................ 38 The Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law — Written evidence (OLC0022) .............................. 41 Chartered Institute of Legal Executives — Written evidence (OLC0017) ................................ 43 Rt Hon Kenneth Clarke MP, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, 2010-12, and Rt Hon Lord Falconer of Thoroton, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs, 2003-07 — Oral Evidence (QQ 76-85) ........................................................................ -

Change in Government: the Agenda for Leadership

House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee Change in Government: the agenda for leadership Thirteenth Report of Session 2010–12 Volume I: Report and Appendices, together with formal minutes and oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the committee website at www.parliament.uk/pasc Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 14 September 2011 HC 714 Published on 22 September 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £17.50 The Public Administration Select Committee The Public Administration Select Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the reports of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration and the Health Service Commissioner for England, which are laid before this House, and matters in connection therewith, and to consider matters relating to the quality and standards of administration provided by civil service departments, and other matters relating to the civil service. Current membership Mr Bernard Jenkin MP (Conservative, Harwich and North Essex) (Chair) Nick de Bois MP (Conservative, Enfield North) Alun Cairns MP (Conservative, Vale of Glamorgan) Michael Dugher MP (Labour, Barnsley East) Charlie Elphicke MP (Conservative, Dover) Paul Flynn MP (Labour, Newport West) Robert Halfon MP (Conservative, Harlow) David Heyes MP (Labour, Ashton under Lyne) Kelvin Hopkins MP (Labour, Luton North) Greg Mulholland MP (Lib Dem, Leeds North West) Lindsay Roy MP (Labour, Glenrothes) The following member was also a member of the Committee during the inquiry. Mr Charles Walker MP (Conservative, Broxbourne) Powers The powers of the Committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 146. -

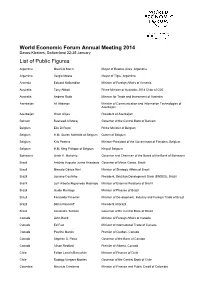

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

TRANSFORMATION in the MINISTRY of JUSTICE 2010 Interim Evaluation Report

TRANSFORMATION IN THE MINISTRY OF JUSTICE 2010 interim evaluation report Tom Gash & Julian McCrae 2 Contents About the Institute for Government 4 About the authors 4 Acknowledgements 5 Executive summary 6 1. Introduction 8 2. The context for Transforming Justice 10 3. Transforming Justice overview 14 4. Methodology 17 5. Findings 24 6. Conclusions 52 Annex 54-60 Evaluation tools 55 Bibliography 57 List of acronyms 59 Endnotes 60 Contents 3 About the Institute of Government The Institute for Government is an independent charity with cross-party and Whitehall governance working to increase government effectiveness. Our funding comes from the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, one of the Sainsbury Family Charitable Trusts. We work with all the main political parties at Westminster and with senior civil servants in Whitehall, providing evidence-based advice that draws on best practice from around the world. We undertake research, provide the highest quality development opportunities for senior decision-makers and organise events to invigorate and provide fresh thinking on the issues that really matter to government. About the authors Tom Gash – Fellow, Institute for Government Tom Gash is a Fellow of the Institute for Government. He joined the Institute in January 2008. Tom previously worked as a consultant in the Boston Consulting Group’s organisation and change practice area and as a Senior Policy Adviser on home affairs in the Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit. Tom specialises in the areas of crime policy and organisational effectiveness, with a special interest in performance management and organisation design. Outside the Institute, he advises overseas governments on public management and strategy development and is currently conducting private research on crime. -

IE Singapore Partners European Bank for Reconstruction and Development to Explore Opportunities

M E D I A RELEASE IE Singapore Partners European Bank for Reconstruction And Development To Explore Opportunities IE Global Conversation With Sir Suma Chakrabarti: The EBRD’s medium to long-term outlook for emerging countries in Europe and central Asia remains positive MR No.: 031/13 Singapore, Monday, 23 September 2013 1. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s (EBRD) medium to long- term outlook for emerging countries in Europe and central Asia like Kazakhstan, Poland, Russia and Turkey, remain positive despite current economic volatilities. Sir Suma Chakrabarti, President of EBRD, shared his optimism on the growth of these emerging markets and opportunities they present for Singapore companies at International Enterprise (IE) Singapore’s Global Conversations held this morning. 2. Moderated by Mr Teo Eng Cheong, Chief Executive Officer of IE Singapore, the business dialogue with Sir Suma engaged 25 senior level representatives from Singapore companies spanning the financial, food, technology, trade and urban solutions sectors. In addition to the EBRD’s economic outlook, discussions revolved around current business trends as well as issues pertinent to Singapore companies in emerging Europe and central Asia. They include market opportunities, challenges and how IE Singapore and EBRD’s close partnership can mitigate risks for companies in these emerging markets. 3. Sir Suma stressed that the economic fundamentals of many emerging countries in Europe and central Asia have improved since the global economic crisis in 2008 / 2009. International Enterprise Singapore is the government agency driving Singapore’s external economy. IE Media Release 23 Sep ’13 Improvements in the Eurozone, efforts by the governments and proximity to the European Union (EU) market are advantages that will help sustain the stability of these emerging markets.