Late Antique Aesthetics, Chromophobia, and the Red Monastery, Sohag, Egypt1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and Main Principals Of

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and main principals of anatomical, pharmaceutical and clinical terminology (Student's book) Simferopol, 2017 Contents No. Topics Page 1. UNIT I. Latin language history. Phonetics. Alphabet. Vowels and consonants classification. Diphthongs. Digraphs. Letter combinations. 4-13 Syllable shortness and longitude. Stress rules. 2. UNIT II. Grammatical noun categories, declension characteristics, noun 14-25 dictionary forms, determination of the noun stems, nominative and genitive cases and their significance in terms formation. I-st noun declension. 3. UNIT III. Adjectives and its grammatical categories. Classes of adjectives. Adjective entries in dictionaries. Adjectives of the I-st group. Gender 26-36 endings, stem-determining. 4. UNIT IV. Adjectives of the 2-nd group. Morphological characteristics of two- and multi-word anatomical terms. Syntax of two- and multi-word 37-49 anatomical terms. Nouns of the 2nd declension 5. UNIT V. General characteristic of the nouns of the 3rd declension. Parisyllabic and imparisyllabic nouns. Types of stems of the nouns of the 50-58 3rd declension and their peculiarities. 3rd declension nouns in combination with agreed and non-agreed attributes 6. UNIT VI. Peculiarities of 3rd declension nouns of masculine, feminine and neuter genders. Muscle names referring to their functions. Exceptions to the 59-71 gender rule of 3rd declension nouns for all three genders 7. UNIT VII. 1st, 2nd and 3rd declension nouns in combination with II class adjectives. Present Participle and its declension. Anatomical terms 72-81 consisting of nouns and participles 8. UNIT VIII. Nouns of the 4th and 5th declensions and their combination with 82-89 adjectives 9. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Tyrian Purple: Its Evolution and Reinterpretation As Social Status Symbol During the Roman Empire in the West

Tyrian Purple: Its Evolution and Reinterpretation as Social Status Symbol during the Roman Empire in the West Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Graduate Program in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Andrew J. Koh, Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies by Mary Pons May 2016 Acknowledgments This paper truly would not have come to be without the inspiration provided by Professor Andrew Koh’s Art and Chemistry class. The curriculum for that class opened my mind to a new paradigmatic shift in my thinking, encouraging me to embrace the possibility of reinterpreting the archaeological record and the stories it contains through the lens of quantifiable scientific data. I know that I would never have had the courage to finish this project if it were not for the support of my advisor Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, who never rejected my ideas as outlandish and stayed with me as I wrote and rewrote draft after draft to meet her high standards of editorial excellence. I also owe a debt of gratitude to my parents, Gary and Debbie Pons, who provided the emotional support I needed to get through my bouts of insecurity. When everything I seemed to put on the page never seemed good enough or clear enough to explain my thought process, they often reminded me to relax, sleep, walk away from it for a while, and try again another day. -

Stephen J. Davis Curriculum Vitae, P

Stephen J. Davis curriculum vitae, p. 1 STEPHEN J. DAVIS Yale University Yale University Pierson College Department of Religious Studies 261 Park Street 451 College Street New Haven, CT 06511 New Haven, CT 06511 Phone: 203-432-1298 Email: [email protected] Fax: 203-432-7844 EDUCATION: Yale University -- M.A. (1993), M.Phil. (1995), Ph.D. (1998), Religious Studies (Ancient Christianity) Dissertation: “The Cult of Saint Thecla, Apostle and Protomartyr: A Tradition of Women’s Piety in Late Antiquity” Duke University, The Divinity School -- M.Div., summa cum laude (1992) Princeton University -- A.B., English Literature (and Hellenic Studies), cum laude (1988) Senior Thesis: “Visions of History: The Poetry of W. B. Yeats and C. P. Cavafy” EMPLOYMENT HISTORY/TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Professor of Religious Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT (2008– ) Affiliate faculty member in the Departments of History and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, the Councils on Archaeological Studies and Middle East Studies, and the Programs in Humanities, Hellenic Studies, and Medieval Studies. Senior Research Fellow at the MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies. Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT (2005–08) Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT (2002–05) Professor of New Testament and Early Church History, Evangelical Theological Seminary in Cairo (ETSC), Cairo, Egypt (1998–2002, visiting spring 2005). ETSC is the official Arabic-language seminary of the Coptic Evangelical -

Pdf (264.94 K)

International Academic Journal of the Faculty of Tourism and Hotel Management Helwan University Volume 2, No.2, 2016 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Challenges Facing Coptic Heritage Tourism in Egypt A Case Study On: Wadifeiran Region Jermien Hussein Abd El-Kafy Tourism Studies, Faculty of Tourism and Hotel Management, Helwan University Abstract Despite the fact that Egypt owns a huge fortune of Coptic heritage sites (i.e. The Monastery of Saint Anthony, El Bagawat Necropolis, the Red Monastery and the White Monastery, etc.), heritage tourism in Egypt is known only by Pharaonic monuments. Accordingly, it is necessary to focus on the Egyptian Coptic heritage. The current paper aims at shedding light on the importance of the Egyptian Coptic heritage as a main component of the Egyptian heritage tourism as well as exploring the different challenges facing Coptic heritage in Wadi Feiran Region. Within this context, interviews were conducted with key representatives of Coptic heritage experts. It was concluded that different challenges are facing Coptic heritage in Egypt such as: there is no department of Coptology in the Egyptian universities; Coptic conservators are quite rare in Egypt; Mismanagement of Coptic heritage sites endanger them as well as Lack of security measures worsened the situation. Key words: Heritage tourism - Coptic heritage - Wadi Feiran - Challenges Facing Egyptian Coptic Heritage – Heritage conservation 1- Introduction Egypt’s heritage varies from Pharaonic, Greek, Roman, Coptic and Islamic. Coptic heritage is considered one of the most important Egyptian heritage components. Coptic heritage includes all life fields; it represents people’s entity and identity. Coptic heritage is not limited to architectural heritage, but it includes Coptic music, Coptic language, Coptic calendar, Coptic literature, Coptic folklore….etc. -

A Geochemical, Petrological and Statistical Approaches

id3760375 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 7, Issue 2, December - 2017: pp: 87-101 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article HISTORICAL BRICKS DETERIORATION AND RESTORATION FROM THE RED MONASTERY, SOHAG, EGYPT: A GEOCHEMICAL, PETROLOGICAL AND STATISTICAL APPROACHES Abd-Elkareem, E.1, Ali, M.2 & El-Sheikh, A.2 1Conservation dept., Faculty of Archaeology, South Valley Univ., Qena, Egypt. 2Geology dept., Faculty of Sciences, Sohag Univ., Sohag, Egypt. E-mail: [email protected] Received 22/1/2017 Accepted 3/5/2017 Abstract The present study investigates for the first time the historical bricks of The Red Monastery (west Sohag, Egypt), built about fifth century AD, which showing several aspects of brick decay. Several techniques were employed (geochemical, petrographical, mineralogical and morphological) to determine their deterioration features and provenance of the raw material as well as shed lights on the firing techniques. In addition, integration of geochemical data with multivariate statistics (i.e. Cluster Analysis, Principal Component Analyses and Linear Discriminant Analyses) were used to provide insights into the nature and provenance of the raw material. Potential geological raw materials for bricks manufacturing, were taken from modern floodplain (Nile alluvium) and calcareous clay deposits from lowland desert near the monument site, and subjected to chemical analyses, to compare them with the chemical composition of the studied bricks. Results show that the starting raw materials for bricks were probably obtained by mixing Nile alluvium (quarried from the Nile River floodplain deposits) with the possible introduction of a calcium carbonate-rich flux component as a temper. -

Nile Valley: Beni Suef to Qena

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Nile Valley: Beni Suef to Qena Includes ¨ Why Go? Beni Suef ...........165 If you’re in a hurry to reach the treasures and pleasures of Gebel at-Teir & the south, it is easy to dismiss this first segment of Upper Frazer Tombs ........166 Egypt between Cairo and Luxor. But the less touristed parts Minya ..............166 of the country almost always repay the effort of a visit. Beni Hasan .........169 Much of this part of the valley is less developed than the other valleys but people here also have to grapple with the Beni Hasan to Tell al-Amarna .......170 issues of modernity, with water and electricity shortages, and since the downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood, with Tell al-Amarna .......170 sectarian tension and security issues. Tombs of Mir ........173 However much a backwater this region might seem, it Deir al-Muharraq ....173 played a key role in Egypt’s destiny as its many archaeolog- Asyut ..............174 ical sites bear witness – from the lavishly painted tombs of Sohag ..............176 the early provincial rulers at Beni Hasan to the remains of Akhetaten, where Tutankhamun was brought up, and the Abydos .............178 Pharaonic-inspired monasteries of the early Christian period. Qena ...............180 Note: due to security concerns, research was conducted remotely by the author for this chapter, except for Dendera, Abydos and Qena. Best Places to Eat When to Go ¨ Koshary Nagwa (p168) Asyut ¨ Dahabiyya Houseboat & °C/°F Temp Rainfall inches/mm Restaurant (p168) 50/122 2.4/60 2.0/50 ¨ Al-Watania Palace Hotel 40/104 1.6/40 (p174) 30/86 1.2/30 20/68 0.8/20 10/50 0.4/10 Best Places to Stay 0/32 0 ¨ Al-Safa Hotel (p177) J FDM A M J J A S O N ¨ Al-Watania Palace Hotel Apr Sham el Aug Millions of Oct-Nov The ideal (p174) Nessim, the spring people arrive to touring time, ¨ City Center Hotel (p166) festival, is cele- celebrate the with the light brated in style in Feast of the Virgin being particularly ¨ Horus Resort (p168) the region. -

Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-De-Siècle France

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Art History Theses and Dissertations Art History Spring 5-15-2021 Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Siècle France Ana Norman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/arts_arthistory_etds Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Norman, Ana, "Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Siècle France" (2021). Art History Theses and Dissertations. 7. https://scholar.smu.edu/arts_arthistory_etds/7 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. MIMING MODERNITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF PIERROT IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE FRANCE Approved by: _______________________________ Dr. Amy Freund Associate Professor of Art History _______________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Eager Assistant Professor of Art History _______________________________ Dr. Randall Griffin Distinguished Professor of Art History !"Doc ID: ec9532a69b51b36bccf406d911c8bbe8b5ed34ce MIMING MODERNITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF PIERROT IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE FRANCE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Meadows School of the Arts Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Art History by Ana Norman B.A., Art History, University of Dallas May 15, 2021 Norman, Ana B.A., Art History, University of Dallas Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Si cle France Advisor: Dr. Amy Freund Master of Art History conferred May 15, 2021 Thesis completed May 3, 2021 This thesis examines the commedia dell’arte character Pierrot through the lens of gender performance in order to decipher the ways in which he complicates and expands understandings of gender and the normative model of sexuality in fin de siècle France. -

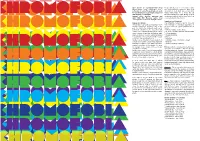

People with the Fear of Colors Tend to Suffer from Many Debilitating

CHROMOFOBIA (also known as chromatophobia) (from People with the fear of colors tend to suffer Greek chroma, “color” and phobos, “fear”) from many debilitating symptoms. Often, they is the fear of colors.The worst place to be in are unable to hold down jobs or even have CHROMOFOBIA for chromophobes is Las Vegas because of steady relationships. As a result, life can CHROMOFOBIA their brightly colored lights. become miserable for them. Going outdoors Famous actor, director, musician and can become a difficult task for them, for the fear writer Billy Bob Thornton suffers from of encountering the hated colors. chromophobia, or the fear of bright colours. Symptoms and treatment Causes and effects The symptoms of effects of fear of color vary This phobia is caused by post traumatic stress from individual to individual depending on CHROMOFOBIA disorder experiences involving colors in the the level of the fear. Typical symptoms are as CHROMOFOBIA past. An event in the childhood might lead to follows: permanent emotional scars associated with * Extreme anxiety or panic attack certain colors or shades which the phobic simply * Shortness of breath- rapid and shallow breaths cannot outgrow. Events like child abuse, rape, * Profuse sweating death, accidents or violence, could all be related * Irregular heartbeat to a particular color causing the phobic to panic * Nausea or become anxious in its presence. * Dry mouth CHROMOFOBIA Another cause of the fear of colors stems from * Inability to speak or formulate coherent cultural roots. Certain cultures have significant sentences CHROMOFOBIA meanings for specific colors which can have a * Shaking, shivering, trembling CHROMOFOBIA negative connotation for the phobic. -

Chromophobia, Or Chromatophobia, Is an Irrational Fear of Certain Colors

Chromophobia, Or Chromatophobia, Is An Irrational Fear Of Certain Colors National Color Day focuses on the affect color has on each of us. The observance takes place each year on October 22. Color is powerful. It can affect a mood, draw attention, even cause alarm. Different colors are perceived to mean different things. The following is one rendition of the perceived meaning of the various colors in the United States. Red: Excitement – Love – Strength Yellow: Competence – Happiness Green: Good Taste – Envy – Relaxation Blue: Corporate – High Quality Pink: Sophistication – Sincerity Violet/Purple: Authority – Power Brown: Ruggedness Black: Grief – Fear White: Happiness – Purity. You’re more likely to forget something when it’s in black and white. Psychologists have found a number of connections between color and memory. As it turns out, people have more trouble remembering facts presented in black and white than they do facts presented in color. There’s a reason you never see yellow in an airplane. A number of studies have shown that the color yellow can cause dizziness and nausea. For this reason, it’s often used sparingly (or very strategically) by those in advertising, and is almost never used in the interiors of various forms of transportation — most notably, airplanes. It’s possible to be afraid of certain colors. Chromophobia, or Chromatophobia, refers to an irrational fear of or aversion to certain colors. Blue is the world’s favorite color. Studies done around the world reveal that a whopping 40% of people consider blue to be their favorite color. Second place goes to purple, though that received only 14%, and last place goes to black. -

Der Blaue Reiter, Walter Benjamin and the Emancipation of Color

Chromophilia: Der Blaue Reiter, Walter Benjamin and the Emancipation of Color Dr. Martin Jay Sidney Hellman Ehrman Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley Prepared for the 2011 Yale University Forum on Art, War and Science in the 20th Century Hosted by The Jeffrey Rubinoff Sculpture Park May 19-23rd 2011 on Hornby Island, British Columbia, Canada “Indelible from the resistance to the fungible world of barter is the resistance of the eye that does not want the colors of the world to fade.” Theodor W. Adorno1 In 2003, the Wilhelm Hack Museum in the city of Ludwigshafen am Rhein mounted an exhibition entitled “Der Blaue Reiter: Die Befreiung der Farbe.”2 In what follows, I want to focus on the provocative subtitle of that show and ask the question, what did the “emancipation of color” mean for the Blaue Reiter, in particular for its most prominent figure, Wassily Kandinsky? The other artists associated with the movement, such as Robert Delauney, Franz Marc, August Macke, Alexander Jawlensky and Paul Klee, were also remarkable chromatic innovators, but Kandinsky was the most articulate spokesman of their more or less common position.3 The language of “emancipation” is , in fact, one he explicitly adopted.4 To help us clarify the stakes of his argument, I will also be examining the fragmentary, posthumously published thoughts on color by a German critic who was himself fascinated by the Blaue Reiter, Walter Benjamin, which have recently been subjected to sustained analysis by Howard Caygill and Heinz Brüggemann.5 In any history of early 20th-century visual modernism, the experiments in color performed by avant-garde communities of artists, such as the Nabis and Fauves in France and Die Brücke in Germany, are routinely foregrounded. -

An Introduction to the Red Monastery Church Elizabeth S. Bolman, Director of the USAID/ARCE Red Monastery Church Conservation Pr

An Introduction to the Red Monastery Church Elizabeth S. Bolman, Director of the USAID/ARCE Red Monastery Church Conservation Project [An abridged version of the Introduction to The Red Monastery Church: Beauty and Asceticism in Upper Egypt, edited by Elizabeth S. Bolman. Yale University Press and the American Research Center in Egypt, 2016, xx-xxxvi. For scholarly references for the information included here, please see the Introduction to the book.] The Red Monastery Church is an extraordinary monument, a beautiful materialization of asceticism and authority. A community of Christian men made the decision a millennium and a half ago to build a large church, thus asserting the social centrality of their ascetic establishment at the Red Monastery. A significant part of that original monument and some of its major renovations still survive in astonishingly good condition, although the church has until very recently not received the renown that is its due. It was designed as a triconch basilica: a building with a rectangular nave, divided into three aisles by two rows of columns, leading to a three- lobed sanctuary. The nave, where the congregation attended religious services, is separated from the sanctuary, which was reserved for priests, by a raised platform with a screen and an interior façade wall. The basic model for the Red Monastery Church was a larger church built a few decades earlier at the nearby White Monastery. Though the trefoil design was popular in the late Roman world, no other example survives in such an excellent state of preservation. Additionally, the early Byzantine decoration of the sanctuary is almost intact and includes rich architectural sculpture, imposing figural compositions, and extensive ornamental paintings.