1 Photography, Race and Invisibility: the Liberation of Paris, in Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DP Musée De La Libération UK.Indd

PRESS KIT LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN The musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin will be ofcially opened on 25 August 2019, marking the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris. Entirely restored and newly laid out, the museum in the 14th arrondissement comprises the 18th-century Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau and the adjacent 19th-century building. The aim is let the general public share three historic aspects of the Second World War: the heroic gures of Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque and Jean Moulin, and the liberation of the French capital. 2 Place Denfert-Rochereau, musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin © Pierre Antoine CONTENTS INTRODUCTION page 04 EDITORIALS page 05 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES page 06 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES A NEW HISTORICAL PRESENTATION page 07 AN EXHIBITION IN STEPS page 08 JEAN MOULIN (¡¢¢¢£¤) page 11 PHILIPPE DE HAUTECLOCQUE (¢§¢£¨) page 12 SCENOGRAPHY: THE CHOICES page 13 ENHANCED COLLECTIONS page 15 3 DONATIONS page 16 A MUSEUM FOR ALL page 17 A HERITAGE SETTING FOR A NEW MUSEUM page 19 THE INFORMATION CENTRE page 22 THE EXPERT ADVISORY COMMITTEE page 23 PARTNER BODIES page 24 SCHEDULE AND FINANCING OF THE WORKS page 26 SPONSORS page 27 PROJECT PERSONNEL page 28 THE CITY OF PARIS MUSEUM NETWORK page 29 PRESS VISUALS page 30 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN INTRODUCTION New presentation, new venue: the museums devoted to general Leclerc, the Liberation of Paris and Resistance leader Jean Moulin are leaving the Gare Montparnasse for the Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science the New

The London School of Economics and Political Science The New Industrial Order: Vichy, Steel, and the Origins of the Monnet Plan, 1940-1946 Luc-André Brunet A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, July 2014 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 87,402 words. 2 Abstract Following the Fall of France in 1940, the nation’s industry was fundamentally reorganised under the Vichy regime. This thesis traces the history of the keystones of this New Industrial Order, the Organisation Committees, by focusing on the organisation of the French steel industry between the end of the Third Republic in 1940 and the establishment of the Fourth Republic in 1946. It challenges traditional views by showing that the Committees were created largely to facilitate economic collaboration with Nazi Germany. -

PDF Download Overlord : D-Day and the Battle for Normandy Ebook

OVERLORD : D-DAY AND THE BATTLE FOR NORMANDY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir Max Hastings | 396 pages | 23 May 1985 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780671554354 | English | New York, NY, United States Overlord : D-Day and the Battle for Normandy PDF Book Hastings, on the whole, provides well-balanced and insightful military histories and this is no exception. Neither had really been fighting—even the bulk of the British men had spent the war defending the isles agains A very good account of the Normandy campaign, from the successful landings on June 6, through the two months of bloody warfare of attrition in the bocages of France, to the breakouts by the Americans that finally broke the German resistance in France. Preparations for D-Day When the Germans conquered France in the spring of , they sealed their victory with a symbolic flourish. Email to friends Share on Facebook - opens in a new window or tab Share on Twitter - opens in a new window or tab Share on Pinterest - opens in a new window or tab. This item will be shipped through the Global Shipping Program and includes international tracking. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. Open Preview See a Problem? In just some of the major battles of the campaign, German tank losses amount to over tanks. The memory of the trauma has faded where some 20 people were killed between and On April 13, , the French State decided to forbid public gatherings and the organization of festivals until mid-July due to the Covid health crisis. British and American planners worked together, but they also worked separately, particularly in the early years of the war. -

Operation-Overlord.Pdf

A Guide To Historical Holdings In the Eisenhower Library Operation OVERLORD Compiled by Valoise Armstrong Page 4 INTRODUCTION This guide contains a listing of collections in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library relating to the planning and execution of Operation Overlord, including documents relating to the D-Day Invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. That monumental event has been commemorated frequently since the end of the war and material related to those anniversary observances is also represented in these collections and listed in this guide. The overview of the manuscript collections describes the relationship between the creators and Operation Overlord and lists the types of relevant documents found within those collections. This is followed by a detailed folder list of the manuscript collections, list of relevant oral history transcripts, a list of related audiovisual materials, and a selected bibliography of printed materials. DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY Abilene, Kansas 67410 September 2006 Table of Contents Section Page Overview of Collections…………………………………………….5 Detailed Folder Lists……………………………………………….12 Oral History Transcripts……………………………………………41 Audiovisual: Still Photographs…………………………………….42 Audiovisual: Audio Recordings……………………………………43 Audiovisual: Motion Picture Film………………………………….44 Select Bibliography of Print Materials…………………………….49 Page 5 OO Page 6 Overview of Collections BARKER, RAY W.: Papers, 1943-1945 In 1942 General George Marshall ordered General Ray Barker to London to work with the British planners on the cross-channel invasion. His papers include minutes of meetings, reports and other related documents. BULKELEY, JOHN D.: Papers, 1928-1984 John Bulkeley, a career naval officer, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1933 and was serving in the Pacific at the start of World War II. -

Compagnon De La Libération “Compagnon De La Libération” *

Compagnon de la Libération “Compagnon de la Libération” * 1 La libération de Paris ne marque pas la fin de la guerre en Europe. The liberation of Paris did not mean the end of the war in Europe. De durs combats se poursuivent où troupes américaines et françaises American and French troops continued to fight side by side in the combattent côte à côte pour libérer le territoire français et pénétrer struggle to liberate French territory, enter Germany, and force the en Allemagne pour imposer, le 8 mai 1945, la capitulation sans unconditional surrender of the Nazi regime on May 8, 1945. Throughout conditions du régime nazi. Durant toute cette période, les soldats this period, American soldiers saw in liberated France a safe territory américains ont pu trouver, dans la France libérée, un territoire sûr managed by a government that knew how to guarantee peace and géré par un gouvernement qui a su garantir la paix et la sécurité security while restoring the laws of the Republic. tout en rétablissant la légalité républicaine. The understanding between Ike and the “Man of June 18, 1940” L’entente personnelle entre le commandant suprême interallié (de Gaulle’s nickname after his broadcast calling on the French et l’homme du 18 juin a donc toujours permis de passer outre to resist Germany’s occupation) always took precedence over aux réticences des présidents américains envers de Gaulle, the reluctance of American presidents towards de Gaulle. It also held 1 2 3 comme à leurs propres différences de conceptions stratégiques, fast despite differences in strategic planning. -

The Germans in France During World War II: Defeat, Occupation, Liberation, and Memory UCB-OLLI Bert Gordon [email protected] Winter 2020

The Germans in France During World War II: Defeat, Occupation, Liberation, and Memory UCB-OLLI Bert Gordon [email protected] Winter 2020 Introduction Collaboration, Resistance, Survival: The Germans in France During World War II - Defeat, Occupation, Liberation, and Memory Shortly before being executed for having collaborated with Nazi Germany during the German occupation of France in the Second World War, the French writer Robert Brasillach wrote that “Frenchmen given to reflection, during these years, will have more or less slept with Germany—not without quarrels—and the memory of it will remain sweet for them.” Brasillach’s statement shines a light on a highly charged and complex period: the four-year occupation of France by Nazi Germany from 1940 through 1944. In the years since the war, the French have continued to discuss and debate the experiences of those who lived through the war and their meanings for identity and memory in France. On 25 August 2019, a new museum, actually a transfer and extension of a previously existing museum in Paris, was opened to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the French capital. Above: German Servicewomen in Occupied Paris Gordon, The Germans in France During World War II: Defeat, Occupation, Liberation, and Memory Our course examines the Occupation in six two-hour meetings. Each class session will have a theme, subdivided into two halves with a ten-minute break in between. Class Schedule: 1. From Victory to Defeat: France emerges victorious after the First World War but fails to maintain its supremacy. 1-A. The Interwar Years: We focus on France’s path from victory in the First World War through their failure to successfully resist the rise of Nazi Germany during the interwar years and their overwhelming defeat in the Second. -

D-Day: Planning Operation OVERLORD

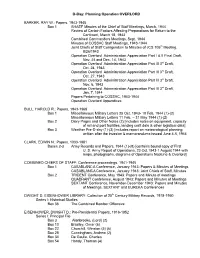

D-Day: Planning Operation OVERLORD BARKER, RAY W.: Papers, 1943-1945 Box 1 SHAEF Minutes of the Chief of Staff Meetings, March, 1944 Review of Certain Factors Affecting Preparations for Return to the Continent, March 18, 1943 Combined Commanders Meetings, Sept. 1944 Minutes of COSSAC Staff Meetings, 1943-1944 Joint Chiefs of Staff Corrigendum to Minutes of JCS 105th Meeting, 8/26/1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part I & II Final Draft, Nov. 24 and Dec. 14, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Oct. 24, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Oct. 27, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Nov. 6, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Jan. 7, 1944 Papers Pertaining to COSSAC, 1943-1944 Operation Overlord Appendices BULL, HAROLD R.: Papers, 1943-1968 Box 1 Miscellaneous Military Letters 25 Oct. 1943- 10 Feb. 1944 (1)-(2) Miscellaneous Military Letters 11 Feb. – 31 May 1944 (1)-(2) Box 2 Diary Pages and Other Notes (2) [includes notes on equipment, capacity of rail and port facilities, landing craft data & other logistical data] Box 3 Weather Pre-D-day (1)-(3) [includes report on meteorological planning written after the invasion & memorandums issued June 4-5, 1944 CLARK, EDWIN N.: Papers, 1933-1981 Boxes 2-3 Army Records and Papers, 1944 (1)-(8) [contains bound copy of First U. S. Army Report of Operations, 23 Oct.1943-1 August 1944 with maps, photographs, diagrams of Operations Neptune & Overlord] COMBINED CHIEFS OF STAFF: Conference proceedings, 1941-1945 Box 1 CASABLANC A Conference, January 1943: Papers & Minutes of Meetings CASABLANCA Conference, January 1943: Joint Chiefs of Staff, Minutes Box 2 TRIDENT Conference, May 1943: Papers and Minute of meetings QUADRANT Conference, August 1943: Papers and Minutes of Meetings SEXTANT Conference, November-December 1943: Papers and Minutes of Meetings, SEXTANT and EUREKA Conferences DWIGHT D. -

BACKGROUND 6 June Shortly After Midnight the 82Nd and 101St

BACKGROUND The Allies fighting in Normandy were a team of teams – from squads and crews through armies, navies and air forces of many thousands. Click below for maps and summaries of critical periods during their campaign, and for the opportunity to explore unit contributions in greater detail. 6 JUNE ~ D-Day 7-13 JUNE ~ Linkup 14-20 JUNE ~ Struggle In The Hedgerows 21-30 JUNE ~ The Fall Of Cherbourg 1-18 JULY ~ To Caen And Saint-Lô 19-25 JULY ~ Caen Falls 26-31 JULY ~ The Operation Cobra Breakout 1-13 AUGUST ~ Exploitation And Counterattack 14-19 AUGUST ~ Falaise And Orleans 20-25 AUGUST ~ The Liberation Of Paris 6 June Shortly after midnight the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions jumped into Normandy to secure bridgeheads and beach exits in advance of the main amphibious attack. Begin- ning at 0630 the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions stormed ashore at Omaha Beach against fierce resistance. Beginning at 0700 the 4th Infantry Division overwhelmed less effective opposition securing Utah Beach, in part because of disruption the airborne landings had caused. By day’s end the Americans were securely ashore at Utah and Commonwealth Forces at Gold, Juno and Sword Beaches. The hold on Omaha Beach was less secure, as fighting continued on through the night of 6-7 June. 1 7-13 June The 1st, 2nd and 29th Infantry Divisions attacked out of Omaha Beach to expand the beachhead and link up with their allies. The 1st linked up with the British and pushed forward to Caumont-l’Êventé against weakening resistance. The 29th fought its way south and west and linked up with forces from Utah Beach, while the 2nd attacked alongside both and secured the interval between them. -

Britain and the French Resistance 1940-1942 : a False Start Laurie West Van Hook

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 1997 Britain and the French Resistance 1940-1942 : a false start Laurie West Van Hook Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Van Hook, Laurie West, "Britain and the French Resistance 1940-1942 : a false start" (1997). Master's Theses. 1304. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses/1304 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRITAIN AND THE FRENCH RESISTANCE 1940-1942: A FALSE START by Laurie West Van Hook M.A., University of Richmond, 1997 Dr. John D. Treadway During the Second World War, the relationship between Great Britain and the French Resistance endured endless problems.From the early days of the war, both sides misunderstood the other and created a stormy relationship, which would never mature later in the war. The French Resistance, initially small and generally fractured, frequently focusedon postwar political maneuvering rather than wartime military tactics. Unificationwas sporadic and tenuous. Charles de Gaulle offered himselfas the leader of the Resistance but lacked experience. This thesis also shows, however, that the British clungto the London-based de Gaulle hastily in the earlydays of the war but quickly decreased their support of him. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was de Gaulle's most ardent supporter, disp1ayed ambivalence and frustration with the general. -

Counter Intelligence Corps History and Mission in World War II

1/ U.S. AR MY MILITARY Hl!3TORYtl$jTlWTE WCS CARLISLE BARRACKS, PA 17013-5008 CIC Wwk!OUNTER INTELLIGENCE CORPS I’ HISTORY AND MISSION IN. WORLD WAR II COUNTER INTELLIGENCE CORPS SCHOOL FORT HOLABIRD BALTIMORE 19, MARYLAND . Special Text BISTGRYAND NISSION \ - IFJ woB[D WARII - - - CIC School Counter Intelligence Corps Center LlU, a‘.* ,’ ARMY WAR COLLEGE - ~Ai%WyE BARFiAdI@, PA, THE CORPSOF INTELLIGENCEPOLICE - CHAPTER1. FROM1917 TO WORLDWAR II Paragraph Page- Purpose and Scope. 1 The Corps of Intelligence Police . 2 : - CHAPTER2. ORGANIZATIONFOR WAR The Corps of Intelligence Police is Geared for Action ....... 5 The Counter Intelligence Corps .............................. 5 Personnel Procurement ....................................... 5 The Problem of Rank......................................... 6 1; CBAPIER3. TBE COUNl’ERITVI’ELLIGENCE CORPS IN THE ZONEOF TIE INTERIOR, 1941-1943 The Military Intelligence Division . ..*.......... 7 13 - PARTTWO _I OPERATIONSOF TIE COWTERINTELLIGENCE CORPS IN THE PRINCIPAL TBEATERS CHAPTER4. OPERATIONSIN NORTHAFRICA The klission . ..*.........................................* 8 The Landing . ..*...........****............. 9 Organization for Operation with Combat Troops . 10 Operations in Liberated Areas . Liaison with United States Intelligence Organizations....... Liaison with Allied Intelligence Organizations.............. 13 Lessons Learned Through Experience . ..*...... 14 Counterintelligence During the Tactical Planning Phases..... 15 Counterintelligence During Mounting Phase of Tactical Operations -

The Underground Resistance in France, Belgium, Holland, and Italy, 1939-1945

http://gdc.gale.com/archivesunbound/ PATRIOTES AUX ARMES! (PATRIOTS TO ARMS!): THE UNDERGROUND RESISTANCE IN FRANCE, BELGIUM, HOLLAND, AND ITALY, 1939-1945 This collection consists of newspapers and periodicals; broadsides; leaflets; and books and pamphlets and other documents produced by or relating to the underground resistance in France, Belgium, Holland, and Italy. Date Range: 1939-1945 Content: 21,348 images Source Library: McMaster University Detailed Description: Resistance movements during World War II occurred in every occupied country by a variety of means, ranging from non-cooperation, disinformation and propaganda to hiding crashed pilots and even to outright warfare and the recapturing of towns. Resistance movements were sometimes referred to as "the underground." Among the most notable resistance movements were the French Forces of the Interior, the Italian CLN, the Belgian Resistance, and the Dutch Resistance. After the first shock following the Blitzkrieg, people slowly started to get organized, both locally and on a larger scale, especially when Jews and other groups were starting to be deported and used for the Arbeitseinsatz (forced labor for the Germans). Organization was dangerous, so much resistance was done by individuals. The possibilities depended much on the terrain; where there were large tracts of uninhabited land, especially hills and forests, resistance could more easily get organized undetected. In countries like the much more densely populated Netherlands, the Biesbosch wilderness could be used to go into hiding. In 1 northern Italy, both the Alps and the Apennines offered shelter to partisan brigades, though many groups operated directly inside the major cities. There were many different types of groups, ranging in activity from humanitarian aid to armed resistance. -

World War II Department

MUSÉE DE L’ARMÉE Presentation of a department The Second World War in the Army Museum This pedagogical course aims at recounting the significant stages of World War II, shedding a light on France’s situation in particular, from the 1940 defeat to the 1944 Liberation. It unfolds through three distinct rooms. The Leclerc room (1939 – 1942) is dedicated to the « années noires » (dark years) during which the Axis perpetrates repeated aggressions. The Juin room (1942 – 1944) evokes the situation of occupied countries as well as the first allied victories. The events leading to the capitulation of Nazi Germany and Japan are presented in the de Lattre room. On this platform, a specific space deals with the discovery of the camps. The course ends with the “conclusive acts” of World War II. Displayed objects and didactic material are organized in successive sequences. Each sequence is indicated by an introducing board briefly indicating the historical context. Audiovisual animations, a total of 32 projections, on both small and large screens, offer montages of filmed archives or specifically designed productions for the illustration of some sequences. The various military campaigns are illustrated through maps and sets of maps which allow following the course of events. What happens before World War II is evoked in the last part of the Foch room dedicated to the interwar years. In 1933, Hitler legally rises to power in Germany and sets up a totalitarian regime. The nazi party provides for the press-ganging of the German population and the ideological indoctrination of the children. This militarization of society is part of the process of preparation to war launched by Hitler.