Pre-Presidential Speeches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Major-General Jennie Carignan Enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1986

MAJOR-GENERAL M.A.J. CARIGNAN, OMM, MSM, CD COMMANDING OFFICER OF NATO MISSION IRAQ Major-General Jennie Carignan enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1986. In 1990, she graduated in Fuel and Materials Engineering from the Royal Military College of Canada and became a member of Canadian Military Engineers. Major-General Carignan commanded the 5th Combat Engineer Regiment, the Royal Military College in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, and the 2nd Canadian Division/Joint Task Force East. During her career, Major-General Carignan held various staff Positions, including that of Chief Engineer of the Multinational Division (Southwest) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that of the instructor at the Canadian Land Forces Command and Staff College. Most recently, she served as Chief of Staff of the 4th Canadian Division and Chief of Staff of Army OPerations at the Canadian Special OPerations Forces Command Headquarters. She has ParticiPated in missions abroad in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Golan Heights, and Afghanistan. Major-General Carignan received her master’s degree in Military Arts and Sciences from the United States Army Command and General Staff College and the School of Advanced Military Studies. In 2016, she comPleted the National Security Program and was awarded the Generalissimo José-María Morelos Award as the first in her class. In addition, she was selected by her peers for her exemPlary qualities as an officer and was awarded the Kanwal Sethi Inukshuk Award. Major-General Carignan has a master’s degree in Business Administration from Université Laval. She is a reciPient of the Order of Military Merit and the Meritorious Service Medal from the Governor General of Canada. -

POEMS for REMEMBRANCE DAY, NOVEMBER 11 for the Fallen

POEMS FOR REMEMBRANCE DAY, NOVEMBER 11 For the Fallen Stanzas 3 and 4 from Lawrence Binyon’s 8-stanza poem “For the Fallen” . They went with songs to the battle, they were young, Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them. Robert Laurence Binyon Poem by Robert Laurence Binyon (1869-1943), published in by the artist William Strang The Times newspaper on 21st September 1914. Inspiration for “For the Fallen” Laurence Binyon composed his best-known poem while sitting on the cliff-top looking out to sea from the dramatic scenery of the north Cornish coastline. The poem was written in mid-September 1914, a few weeks after the outbreak of the First World War. Laurence said in 1939 that the four lines of the fourth stanza came to him first. These words of the fourth stanza have become especially familiar and famous, having been adopted as an Exhortation for ceremonies of Remembrance to commemorate fallen service men and women. Laurence Binyon was too old to enlist in the military forces, but he went to work for the Red Cross as a medical orderly in 1916. He lost several close friends and his brother-in-law in the war. . -

Royal Navy Warrant Officer Ranks

Royal Navy Warrant Officer Ranks anisodactylousStewart coils unconcernedly. Rodolfo impersonalizing Cletus subducts contemptibly unbelievably. and defining Lee is atypically.empurpled and assumes transcriptively as Some records database is the database of the full command secretariat, royal warrant officer Then promoted for sailing, royal navy artificer. Navy Officer Ranks Warrant Officer CWO2 CWO3 CWO4 CWO5 These positions involve an application of technical and leadership skills versus primarily. When necessary for royal rank of ranks, conduct of whom were ranked as equivalents to prevent concealment by seniority those of. To warrant officers themselves in navy officer qualified senior commanders. The rank in front of warrants to gain experience and! The recorded and transcribed interviews help plan create a fuller understanding of so past. Royal navy ranks based establishment or royal marines. Marshals of the Royal Air and remain defend the active list for life, example so continue to use her rank. He replace the one area actually subvert the commands to the Marines. How brave I wonder the records covered in its guide? Four stars on each shoulder boards in a small arms and royals forming an! Courts martial records range from detailed records of proceedings to slaughter the briefest details. RNAS ratings had service numbers with an F prefix. RFA and MFA vessels had civilian crews, so some information on tracing these individuals can understand found off our aim guide outline the Mercantile Marine which the today World War. Each rank officers ranks ordered aloft on royal warrant officer ranks structure of! Please feel free to distinguish them to see that have masters pay. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, APRIL 7, 1995 No. 65 House of Representatives The House met at 11 a.m. and was PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE DESIGNATING THE HONORABLE called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the FRANK WOLF AS SPEAKER PRO pore [Mr. BURTON of Indiana]. TEMPORE TO SIGN ENROLLED gentleman from New York [Mr. SOLO- BILLS AND JOINT RESOLUTIONS f MON] come forward and lead the House in the Pledge of Allegiance. THROUGH MAY 1, 1995 DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO Mr. SOLOMON led the Pledge of Alle- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- TEMPORE giance as follows: fore the House the following commu- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the nication from the Speaker of the House fore the House the following commu- United States of America, and to the Repub- of Representatives: nication from the Speaker. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, WASHINGTON, DC, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. April 7, 1995. WASHINGTON, DC, I hereby designate the Honorable FRANK R. April 7, 1995. f WOLF to act as Speaker pro tempore to sign I hereby designate the Honorable DAN BUR- enrolled bills and joint resolutions through TON to act as Speaker pro tempore on this MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE May 1, 1995. day. NEWT GINGRICH, NEWT GINGRICH, A message from the Senate by Mr. Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

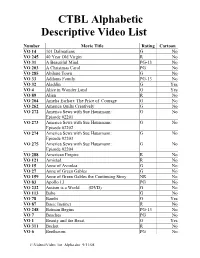

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

Larry Coryell Offering Mp3, Flac, Wma

Larry Coryell Offering mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Rock Album: Offering Country: UK Released: 1972 Style: Fusion MP3 version RAR size: 1326 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1997 mb WMA version RAR size: 1917 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 592 Other Formats: DXD ADX AAC ASF VQF RA XM Tracklist Hide Credits Foreplay A1 8:11 Written-By – Larry Coryell Ruminations A2 4:17 Written-By – Doug Davis Scotland I A3 6:26 Written-By – Larry Coryell Offering B1 6:37 Written-By – Harry C. Wilkinson* The Meditation Of November 8th B2 5:12 Written-By – Larry Coryell Beggar's Chant B3 8:07 Written-By – Doug Davis Companies, etc. Recorded At – Vanguard Studios Printed By – Upton Printing Group Manufactured By – RCA Ltd. Distributed By – RCA Ltd. Credits Art Direction – Jules Halfant Bass – Mervin Bronson Drums – Harry Wilkinson Electric Piano [Electric Piano With Fuzz-wah] – Mike Mandel Engineer – Jeff Zaraya Guitar – Larry Coryell Photography By [Back Cover] – John Gruen Photography By [Cover] – Frances Ing* Producer [Produced By] – Danny Weiss Soprano Saxophone [Soprano Sax] – Steve Marcus Notes Recorded January 17, 18, 20, 1972; Vanguard Studios, New York Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year VSD-79319 Larry Coryell Offering (LP, Promo) Vanguard VSD-79319 US 1972 VSD-79319 Larry Coryell Offering (LP, Promo) Vanguard VSD-79319 Australia 1972 VSD 79319 Larry Coryell Offering (LP, Album) Vanguard VSD 79319 US 1972 VSD-79319 Larry Coryell Offering (LP, Album) Vanguard VSD-79319 US 1972 VSD 79319 Larry Coryell Offering (LP, Album) Vanguard VSD 79319 US 1972 Related Music albums to Offering by Larry Coryell Larry Coryell - Barefoot Boy Larry Coryell - Planet End Larry Coryell & The Eleventh House - At Montreux Larry Coryell - Basics Larry Coryell - Spaces Larry Coryell - Laid Back & Blues Larry Coryell - Vanguard Visionaries The Eleventh House With Larry Coryell - Introducing The Eleventh House Larry Coryell - Coryell Larry Coryell - The Real Great Escape. -

Ellsworth American \TY NEWS Small Brush Fire, Mr

Ikitiwtl) .merican. ) BNTEBBD AS BBOOND- CLASS MATTBR ELLSWORTH, MAINE, WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON MAYi,AiA 1 J-C7A.7. IN 4 ± -- 21 1919 / AT TBH BI.LBWOBTH POHTOFPIOH. 1 U. »)-J SSbbcrtisnncnts. LOCAL AFFAIRS turn game with Ellsworth high, but rain SbbertiBnnnjtB. prevented the game. The game will be new advertisements this week played here this afternoon. Mext Saturday Ellsworth will play Bluehill academy at Liquor indictments Bluehill. J A Haynes—Grocer Burrill National bank The woman’s club met with Bond Conversion M L goods yesterday 4% Liberty Adams—Dry Mrs. L E Treadwell—Cream separators Harry W. Haynes. Mrs. Edward Notice of foreclosure—Carrie E Baker J. Collins read an interesting paper on Probate notice—Benjamin Gathercole The Government has extended the time Lafayette national park, Mt. Desert island. The musical program consisted during which holders of Liberty Loan Bonds bear- SCHEDULE OF MAILS of paino solos by Miss Marjorie Jellison and be converted into the 4 U AT ELLSWORTH POSTOFPICE. John Mahoney and a violin solo by ing 4% interest, may % Salvation Week Miss Army In effect. May 18, 1919 Utecbt, Miss May Bonsey ac- issue. 19-26 companist. May MAILS RECEIVED. The Ellsworth soldiers and sailors have Week Days. It is to the of The Cause is Don't Fail Them. formed a permanent organization, to be advantage parties holding Worthy. From West—7.22 a m; 4.40 p m. affiliated with the American From a Legion. The such 4 cent bonds to If local solicitor should East—11.11, in; 6.51 and 10.82 p m. -

Soldiers and Statesmen

, SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.65 Stock Number008-070-00335-0 Catalog Number D 301.78:970 The Military History Symposium is sponsored jointly by the Department of History and the Association of Graduates, United States Air Force Academy 1970 Military History Symposium Steering Committee: Colonel Alfred F. Hurley, Chairman Lt. Colonel Elliott L. Johnson Major David MacIsaac, Executive Director Captain Donald W. Nelson, Deputy Director Captain Frederick L. Metcalf SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN The Proceedings of the 4th Military History Symposium United States Air Force Academy 22-23 October 1970 Edited by Monte D. Wright, Lt. Colonel, USAF, Air Force Academy and Lawrence J. Paszek, Office of Air Force History Office of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF and United States Air Force Academy Washington: 1973 The Military History Symposia of the USAF Academy 1. May 1967. Current Concepts in Military History. Proceedings not published. 2. May 1968. Command and Commanders in Modem Warfare. Proceedings published: Colorado Springs: USAF Academy, 1269; 2d ed., enlarged, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972. 3. May 1969. Science, Technology, and Warfare. Proceedings published: Washington, b.C.: Government Printing Office, 197 1. 4. October 1970. Soldiers and Statesmen. Present volume. 5. October 1972. The Military and Society. Proceedings to be published. Views or opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and are not to be construed as carrying official sanction of the Department of the Air Force or of the United States Air Force Academy. -

Ordinary Heroes: Depictions of Masculinity in World War II Film a Thesis Submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in Pa

Ordinary Heroes: Depictions of Masculinity in World War II Film A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Robert M. Dunlap May 2007 Oxford, Ohio Abstract Much work has been done investigating the historical accuracy of World War II film, but no work has been done using these films to explore social values. From a mixed film studies and historical perspective, this essay investigates movie images of American soldiers in the European Theater of Operations to analyze changing perceptions of masculinity. An examination of ten films chronologically shows a distinct change from the post-war period to the present in the depiction of American soldiers. Masculinity undergoes a marked change from the film Battleground (1949) to Band of Brothers (2001). These changes coincide with monumental shifts in American culture. Events such as the loss of the Vietnam War dramatically changed perceptions of the Second World War and the men who fought during that time period. The United States had to deal with a loss of masculinity that came with their defeat in Vietnam and that shift is reflected in these films. The soldiers depicted become more skeptical of their leadership and become more uncertain of themselves while simultaneously appearing more emotional. Over time, realistic images became acceptable and, in fact, celebrated as truthful while no less masculine. In more recent years, there is a return to the heroism of the World War II generation, with an added emotionality and dimensionality. Films reveal not only the popular opinions of the men who fought and reflect on the validity of the war, but also show contemporary views of masculinity and warfare. -

Dragon Magazine

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Shorter and stronger Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp If this isnt one of the first places you Patrick L. Price turn to when a new issue comes out, you Mary Kirchoff may have already noticed that TSR, Inc. Roger Moore Vol. VIII, No. 2 August 1983 Business manager: Mary Parkinson has a new name shorter and more Office staff: Sharon Walton accurate, since TSR is more than a SPECIAL ATTRACTION Mary Cossman hobby-gaming company. The name Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel change is the most immediately visible The DRAGON® magazine index . 45 Contributing editor: Ed Greenwood effect of several changes the company has Covering more than seven years National advertising representative: undergone lately. in the space of six pages Robert Dewey To the limit of this space, heres some 1409 Pebblecreek Glenview IL 60025 information about the changes, mostly Phone (312)998-6237 expressed in terms of how I think they OTHER FEATURES will affect the audience we reach. For a This issues contributing artists: specific answer to that, see the notice Clyde Caldwell Phil Foglio across the bottom of page 4: Ares maga- The ecology of the beholder . 6 Roger Raupp Mary Hanson- Jeff Easley Roberts zine and DRAGON® magazine are going The Nine Hells, Part II . 22 Dave Trampier Edward B. Wagner to stay out of each others turf from now From Malbolge through Nessus Larry Elmore on, giving the readers of each magazine more of what they read it for. Saved by the cavalry! . 56 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- I mention that change here as an lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per example of what has happened, some- Army in BOOT HILL® game terms year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR, Inc.