Act One: Scene One the Build-Up and the Breakaway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directions to St Albans Courthouse

The best way to the St Albans Courthouse, Homestead and Stables is to take the Webbs Creek vehicular ferry via Wisemans Ferry (this Ferry is FREE and runs 24hr). Please note that there are 2 ferry services in Wisemans Ferry. NB: There is no mobile recepJon beyond Wisemans Ferry – therefore we recommend that you have a printed copy of the direcJons. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR GPS USERS If you have the "Ferry" opJon switched off on your GPS, you will be sent the long way on a dirt 4WD track. This will increase your journey by at least an hour, and is a narrow, steep, twisty and hard to negoate. Check your GPS sengs or follow the driving direcJons below. The best GPS direcons: IniJally enter the following address: 3004 River Rd, Wisemans Ferry NSW 2775. This address will direct you to the Webbs Creek vehicle Ferry crossing. Join the queue and take the vehicle ferry across the Hawkesbury River to Webbs Creek. On disembarking the ferry, follow this road to the right for 21kms, go straight past the St Albans bridge, and take the NEXT driveway on the leY. Southern & Eastern Suburbs, (Airport) Direc8ons Travel via Eastern Distributor, Harbour Bridge or Harbour Tunnel, along Warringah express way (M1). ConJnue through the Lane Cove tunnel, then along the M2 taking the Pennant Hill Rd A28 exit. Turn right at top of ramp, on to Pennant Hills Rd A28 and conJnue a short distance(1.2km) taking the leY exit onto Castle Hill Rd. ConJnue in right lane turning right at the 2nd set of lights (650m) into New Line Rd. -

Hazard and Risk in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley

HAZARD AND RISK IN THE HAWKESBURY-NEPEAN VALLEY Annex A Supporting document (NSW SES Response Arrangements for Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley) to the Hawkesbury-Nepean Flood Plan Last Update: June 2020 Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Flood Plan Version 2020-0.11 CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 LIST OF MAPS ................................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................................ 2 VERSION LIST ................................................................................................................................................... 3 AMENDMENT LIST ........................................................................................................................................... 3 PART 1 THE FLOOD THREAT ................................................................................................................. 4 PART 2 EFFECTS OF FLOODING ON THE COMMUNITY ........................................................................ 25 Flood Islands ....................................................................................................................... -

May—June 2015 President’S Report

Large & Small Feeder Sizes The BEST SLOW FEEDER Hay Bag on the Market! Quick & Super Easy to Fill Minimizes Hay Waste - Saves YOU Money Benefits Your Horse by Slow Feeding www.haymaximizer.com.au or P: 0429 99 55 96 Saddle Cloths are different…… Here’s Why ! High Density Pure Wool Knitted Fleece breathes, allowing the horse to perspire naturally, minimises heat build up & heat bumps! No edge binding A wide range of Saddle Ties to cause rubbing Designs / Styles standard available Knitted wool available in Natural, Silver & Girth Guides Charcoal standard D-Lua Park Pure Wool Saddle Cloths have no seams, are cut from one piece of material, are highly flexible to allow gap over the wither. Machine Washable in warm water , colours will not bleed. Long life is assured if adequately maintained. Shop Online Brook Sample, Web: www. d-luapark.com.au MultiTom Quilty Contact Winner , Uses & E: [email protected] Recommends P: (07) 54 644 222 %URRN6DPSOH D-Lua Park M: 0427 976 450 Saddle Cloths Contents Advertisers Articles and Results Dixon Smith Back Cover Dinka Dekaris Tumut Ride 53 D-Lua Park Inside Front Cover Homewood Ride Report 47 Muddy Creek Inside Back Cover Homewood Ride Results 50 Sun Tec Enterprises Inside Back Cover Bumbaldry Ride Results 35 Bumbaldry Ride Report 30 Williams Valley Ride Results 16 Reports & Notices Williams Valley Ride Report 13 Letter to Editor 42 Windeyer Ride Results 11 Meeting Report 16 January 2015 36 Windeyer Twilight Ride Report 8 Meeting Report 20 February 2015 57 Ilona Hudson 17 Meeting Report 7 February -

Act Three: Scene One the View from Above

Act Three: The View from Above Scene One The DMR observer in the helicopter was Hal Gregge. He describes what it was like looking down from above: “Anything on a main road is our responsibility, so with a thing like the ferries, the buck stops with us. The helicopter pilot was called Noel and the fellow we were reporting to was Bill McIntyre who was running the workshop at Granville. That was our central workshop - we had all trades and 400 people working there then. We used to support all the ferries from there - they had riggers and people like that and we’d overhaul the ferry engines there. We used to have the patterns to cast the spider wheels, even. It’s all closed down now, though. Bill was organising ground support. He’s retired now. “By the time the helicopter got up to Wisemans, we found noth- ing there. Noel is a very good pilot. He did his training all over the world and has been under fire and everything, so we were able to fly quite low at times when we needed to. We zoomed in around Webbs Creek. There was a set of piers there that they normally tie the ferry to, but of course they were empty. We went around the corner to the piles for the other two ferries, but they’d gone, too. So we just followed the river down at a reasonable height. It wasn’t a bad day on the Tuesday - the flood was well up, but the cloud and rain were gone. -

Berowra Waters Ferry Ramp Upgrade Review of Environmental Factors Roads and Maritime Services | July 2019

Berowra Waters Ferry Ramp Upgrade Review of Environmental Factors Roads and Maritime Services | July 2019 BLANK PAGE Berowra Waters Ferry Ramp Upgrade Review of Environmental Factors Roads and Maritime Services | July 2019 Prepared by NGH Environmental, Sure Environmental and Roads and Maritime Services Copyright: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of NSW Roads and Maritime Services. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of NSW Roads and Maritime Services constitutes an infringement of copyright. Document controls Approval and authorisation Title Berowra Waters Ferry Ramp Upgrade review of environmental factors Accepted on behalf of NSW Joshua Lewis Roads and Maritime Services Project Manager by: Signed: Dated: Executive summary The proposal The car ferry at Berowra Waters provides access between Berowra, Berowra Waters and Berrilee, in the far northern suburbs of Sydney. It is maintained and operated by Roads and Maritime Services NSW (Roads and Maritime). Roads and Maritime proposes to upgrade the ferry ramps at Berowra Waters with precast concrete panels for the sections below the tide level and poured in situ ramp sections above the high water mark. Need for the proposal The proposal is required to maintain a safe ingress and egress for pedestrians and vehicles approaching the ferry. Maintenance inspections indicate the existing ferry ramps are showing signs of degradation that could pose a safety hazard for pedestrians and vehicles. Without a safe operating ferry at Berowra Waters motorist travelling between Berrilee and Berowra would be required to detour via Galston, a detour of about 19 kilometres. -

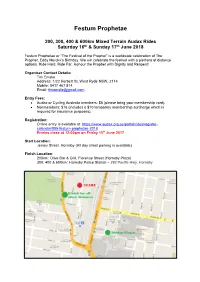

Festum Prophetae

Festum Prophetae 200, 300, 400 & 600km Mixed Terrain Audax Rides Saturday 16th & Sunday 17th June 2018 Festum Prophetae or "The Festival of the Prophet" is a worldwide celebration of The Prophet, Eddy Merckx's Birthday. We will celebrate the festival with a plethora of distance options. Ride Hard. Ride Far. Honour the Prophet with Dignity and Respect! Organiser Contact Details: Tim Emslie Address: 1/22 Herbert St, West Ryde NSW, 2114 Mobile: 0417 467 814 Email: [email protected] Entry Fees: • Audax or Cycling Australia members: $6 (please bring your membership card). • Nonmembers: $16 (includes a $10 temporary membership surcharge which is required for insurance purposes). Registration: Online entry is available at: https://www.audax.org.au/portal/rides/register- calendar/885-festum-prophetae-2018 Entries close at 12:00pm on Friday 15th June 2017 Start Location: Jersey Street, Hornsby (All day street parking is available) Finish Location: 200km: Olive Bar & Grill, Florence Street (Hornsby Plaza) 300, 400 & 600km: Hornsby Police Station – 292 Pacific Hwy, Hornsby Start Time: The ride starts at 6:00am sharp. Please arrive by 5:45am for admin and light check. Please arrive ready for the lighting and reflective vest inspection. Lighting: The maximum ride time for all rides is outside daylight hours, therefore Audax lighting rules do apply. Lighting rules can be viewed on the Audax website (follow the links below). There will be an inspection prior to commencing the ride. Lighting: http://audax.org.au/public/images/stories/Documents/lightingrequirements.pdf Reflective Vest: http://audax.org.au/public/images/stories/Documents/reflectivegarments.pdf Food/water: This ride is unsupported however food and water is readily available along the route and at the control locations. -

The Great North Road

THE GREAT NORTH ROAD NSW NOMINATION FOR NATIONAL ENGINEERING LANDMARK Engineering Heritage Committee Newcastle Division Institution of Engineers, Australia May 2001 Introduction The Newcastle Division's Engineering Heritage Committee has prepared this National Engineering Landmark plaque nomination submission for the total length of the Great North Road from Sydney to the Hunter Valley, NSW. The Great North Road was constructed between 1826 and 1836 to connect Sydney to the rapidly developing Hunter Valley area. It was constructed using convict labour, the majority in chain gangs, under the supervision of colonial engineers, including Lieutenant Percy Simpson. Arrangements have been made to hold the plaquing ceremony on the 13 October 2001 to coincide with the National Engineering Heritage Conference in Canberra the previous week. Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir AC, Governor of New South Wales, has accepted our invitation to attend the plaquing ceremony as our principal guest. A copy of the Governor's letter of acceptance is attached. Clockwise from top left: general view downhill before pavement resurfacing; culvert outlet in buttress; buttressed retaining wall; new entrance gates, and possible plaque position, at bottom of Devines Hill; typical culvert outlet in retaining wall. Commemorative Plaque Nomination Form To: Commemorative Plaque Sub-Committee Date: 22 May 2001 The Institution of Engineers, Australia From: Newcastle Division Engineering House Engineering Heritage Committee 11 National Circuit (Nominating Body) BARTON ACT 2600 The following work is nominated for a National Engineering Landmark Name of work: Great North Road, NSW Location: From Sydney to the Hunter Valley via Wisemans Ferry and Wollombi (over 240 km in length) Owner: Numerous bodies including NSW Roads & Traffic Authority, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service (NPWS), local councils and private landowners (proposed plaque site located on NPWS land). -

History by 1794, Settlers Had Moved Into the Area West of Wisemans Ferry and Grain and Other Crops Were Being Grown for the Colony

Located 20km from McGrath’s Hill and 85km from the centre of Sydney, Wisemans Ferry is now a quaint settlement, a few shops and, most importantly, a ferry across the Hawkesbury River providing access to St Albans, the Hunter Valley and Gosford. Wisemans Ferry is not so much a town as a fascinating relic on the banks of the Hawkesbury River. The Park near the ferry is an ideal location for large family get togethers or a day next to this historic river. A kiosk is located within the park for those last minute items left behind in the haste to pack the car. History By 1794, settlers had moved into the area west of Wisemans Ferry and grain and other crops were being grown for the colony. These early farmers provided Sydney Town with almost half its food supply. The produce was delivered by boat down the Hawkesbury River, a situation which saw Wisemans Ferry rapidly develop as an important river port, out into the Pacific Ocean and around into Sydney Harbour. This was the beginning of a riverboat industry, which continued throughout the 19th Century. In 1805, Solomon Wiseman had been convicted of stealing timber from barges on the River Thames, in London, and transported to New South Wales. It is also reported in some quarters that he was found guilty of smuggling French spies into England along with contraband whiskey. In 1816 he settled at what was then called Lower Portland Head, now Wisemans Ferry and by 1821 was operating an Inn called, “Sign of the Packet.” An astute businessman he managed to get himself assigned to his wife, Jane, who had also come to this country. -

Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Regional Flood Study

INFRASTRUCTURE NSW HAWKESBURY-NEPEAN VALLEY REGIONAL FLOOD STUDY FINAL REPORT VOLUME 1 – MAIN REPORT JULY 2019 HAWKESBURY-NEPEAN VALLEY REGIONAL FLOOD STUDY Level 2, 160 Clarence Street FINAL REPORT Sydney, NSW, 2000 Tel: (02) 9299 2855 Fax: (02) 9262 6208 Email: [email protected] 26 JULY 2019 Web: www.wmawater.com.au Project Project Number Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Regional Flood Study 113031-07 Client Client’s Representative Infrastructure NSW Sue Ribbons Authors Prepared by Mark Babister MER Monique Retallick Mikayla Ward Scott Podger Date Verified by 26 Jul 2019 MKB Revision Description Distribution Date 7 Final Report Public release Jul 2019 Final Draft Infrastructure NSW, local councils, Jan 2019 6 state agencies, utilities, ICA 5 Final Draft for Client Review Infrastructure NSW Oct 2018 Infrastructure NSW, local councils, 4 Final Draft for External Review state agencies, independent technical Sep 2018 review 3 Revised Draft Infrastructure NSW Jul 2018 2 Preliminary Draft Infrastructure NSW May 2018 1 Working Draft WMAwater Jul 2017 COPYRIGHT NOTICE Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Regional Flood Study © State of New South Wales 2019 ISBN 978-0-6480367-0-8 Infrastructure NSW commissioned WMAwater Pty Ltd to develop this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Infrastructure NSW shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. -

Hawkesbury River Cruise 2008

HAWKESBURY RIVER CRUISE 2008 This amazing waterway north of Sydney was the playground for three Whittley cruisers. Two 2800’s, Time Out and Chill Pill and one 660 Cruiser, Zero Tolerance took part in this Christmas cruise. Six adults and 4 children were comfortably accommodated. The crews were as follows. Chill Pill Darren and Tracy Cain with Minnie the dog Time Out Wayne and Maria Taylor with Aiden and Ashley and Chloe the dog Zero Tolerance Stuart and Annette Malone with Lachlan and Ethan Time Out and Chill Pill left Melbourne Boxing Day heading to Goulburn for the night. Ar- riving at Brooklyn the next day the boats were launched and docked at Fenwick’s Marina for the night. The following day Zero Tolerance arrived direct from Shepparton. With the boat launched preparations were made which included inflation of our tenders, necessary when exploring the river system. Rock strewn banks covered with oyster shells and great tidal heights made pulling into the banks impossible. So anchoring or attaching to a mooring and deploying the tender became an everyday occurrence if the shore was to be explored. We planned to see the New Year in watching the fireworks from Sydney harbor. Wayne Taylor heard Athol Bay near the Taronga Zoo was the prime location to view the fireworks. We planned to take the 22 nautical mile ocean trip from the Hawkesbury river to Sydney harbor. Since none of us had been out in the ocean before, we thought it would be prudent to go early in the morning before any wind picked up. -

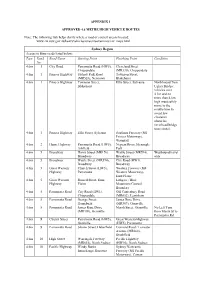

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The following link helps clarify where a road or council area is located: www.rta.nsw.gov.au/heavyvehicles/oversizeovermass/rav_maps.html Sydney Region Access to State roads listed below: Type Road Road Name Starting Point Finishing Point Condition No 4.6m 1 City Road Parramatta Road (HW5), Cleveland Street Chippendale (MR330), Chippendale 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Sydney Park Road Townson Street, (MR528), Newtown Blakehurst 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Townson Street, Ellis Street, Sylvania Northbound Tom Blakehurst Ugly's Bridge: vehicles over 4.3m and no more than 4.6m high must safely move to the middle lane to avoid low clearance obstacles (overhead bridge truss struts). 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Ellis Street, Sylvania Southern Freeway (M1 Princes Motorway), Waterfall 4.6m 2 Hume Highway Parramatta Road (HW5), Nepean River, Menangle Ashfield Park 4.6m 5 Broadway Harris Street (MR170), Wattle Street (MR594), Westbound travel Broadway Broadway only 4.6m 5 Broadway Wattle Street (MR594), City Road (HW1), Broadway Broadway 4.6m 5 Great Western Church Street (HW5), Western Freeway (M4 Highway Parramatta Western Motorway), Emu Plains 4.6m 5 Great Western Russell Street, Emu Lithgow / Blue Highway Plains Mountains Council Boundary 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road City Road (HW1), Old Canterbury Road Chippendale (MR652), Lewisham 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road George Street, James Ruse Drive Homebush (MR309), Granville 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road James Ruse Drive Marsh Street, Granville No Left Turn (MR309), Granville -

Yananda Yoga and Meditation Retreat

Relax and Renew Yoga and Meditation Retreat October 12th -15th 2020 Taking time out is vital to our life, health and longevity. A few days away to unwind, relax and restore your inner balance. Unplug from the pressures of life and daily routine. Yanada is a beautiful tranquil location just two hours out of Sydney. A perfect location to restore, relax and restore body and mind, connect more deeply with yourself and nature. Your retreat will include: All meals and accomodation. Meditation and Yoga: 2 hr sunrise and sunset yoga and meditation energy balancing meridian yoga healing, balancing and restoring, calming and relaxing nourishing mind, body and soul. Reflection Enjoy ample time reconnecting with yourself and nature. Nourish yourself with rest, yoga, healthy food, nature and time out. Medicine for mind and body. Where: Yanada is a beautiful six bedroom property set on 38 acres in Darkinjung country, nestled between the McDonald River and the Yengo Mountains. 2km outside the historic village of St Albans and 17 km from Wiseman's Ferry and the Hawkesbury River. The setting is remote and idyllic with complete privacy assured; you will unwind as soon as you enter the driveway. Take a deep breath... And arrive ૐ Yanada is a convenient 90 minutes’ drive from Sydney CBD, located in the McDonald Valley 2km outside the historic village of St Albans. Adjoining Yengo National Park and are 17 minutes from Wiseman's Ferry and the Hawkesbury River. This is the southern tip of Darkinjung country with Mount Yengo at its heart. This place is hidden and remote, known since first European settlement as the Forgotten Valley, yet less than 2 hours’ drive from Sydney.