Act Three: Scene One the View from Above

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directions to St Albans Courthouse

The best way to the St Albans Courthouse, Homestead and Stables is to take the Webbs Creek vehicular ferry via Wisemans Ferry (this Ferry is FREE and runs 24hr). Please note that there are 2 ferry services in Wisemans Ferry. NB: There is no mobile recepJon beyond Wisemans Ferry – therefore we recommend that you have a printed copy of the direcJons. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR GPS USERS If you have the "Ferry" opJon switched off on your GPS, you will be sent the long way on a dirt 4WD track. This will increase your journey by at least an hour, and is a narrow, steep, twisty and hard to negoate. Check your GPS sengs or follow the driving direcJons below. The best GPS direcons: IniJally enter the following address: 3004 River Rd, Wisemans Ferry NSW 2775. This address will direct you to the Webbs Creek vehicle Ferry crossing. Join the queue and take the vehicle ferry across the Hawkesbury River to Webbs Creek. On disembarking the ferry, follow this road to the right for 21kms, go straight past the St Albans bridge, and take the NEXT driveway on the leY. Southern & Eastern Suburbs, (Airport) Direc8ons Travel via Eastern Distributor, Harbour Bridge or Harbour Tunnel, along Warringah express way (M1). ConJnue through the Lane Cove tunnel, then along the M2 taking the Pennant Hill Rd A28 exit. Turn right at top of ramp, on to Pennant Hills Rd A28 and conJnue a short distance(1.2km) taking the leY exit onto Castle Hill Rd. ConJnue in right lane turning right at the 2nd set of lights (650m) into New Line Rd. -

Hazard and Risk in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley

HAZARD AND RISK IN THE HAWKESBURY-NEPEAN VALLEY Annex A Supporting document (NSW SES Response Arrangements for Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley) to the Hawkesbury-Nepean Flood Plan Last Update: June 2020 Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Flood Plan Version 2020-0.11 CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 LIST OF MAPS ................................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................................ 2 VERSION LIST ................................................................................................................................................... 3 AMENDMENT LIST ........................................................................................................................................... 3 PART 1 THE FLOOD THREAT ................................................................................................................. 4 PART 2 EFFECTS OF FLOODING ON THE COMMUNITY ........................................................................ 25 Flood Islands ....................................................................................................................... -

BROOKLYN ESTUARY PROCESS STUDY (VOLUME I of II) By

BROOKLYN ESTUARY PROCESS STUDY (VOLUME I OF II) by Water Research Laboratory Manly Hydraulics Laboratory The Ecology Lab Coastal and Marine Geosciences The Centre for Research on Ecological Impacts of Coastal Cities Edited by B M Miller and D Van Senden Technical Report 2002/20 June 2002 (Issued October 2003) THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES SCHOOL OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING WATER RESEARCH LABORATORY BROOKLYN ESTUARY PROCESS STUDY WRL Technical Report 2002/20 June 2002 by Water Research Laboratory Manly Hydraulics Laboratory The Ecology Lab Coastal and Marine Geosciences The Centre for Research on Ecological Impacts of Coastal Cities Edited by B M Miller D Van Senden (Issued October 2003) - i - Water Research Laboratory School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Technical Report No 2002/20 University of New South Wales ABN 57 195 873 179 Report Status Final King Street Date of Issue October 2003 Manly Vale NSW 2093 Australia Telephone: +61 (2) 9949 4488 WRL Project No. 00758 Facsimile: +61 (2) 9949 4188 Project Manager B M Miller Title BROOKLYN ESTUARY PROCESS STUDY Editor(s) B M Miller, D Van Senden Client Name Hornsby Shire Council Client Address PO Box 37 296 Pacific Highway HORNSBY NSW 1630 Client Contact Jacqui Grove Client Reference Major Involvement by: Brett Miller (WRL), David van Senden (MHL), William Glamore (WRL), Ainslie Fraser (WRL), Matt Chadwick (WRL), Peggy O'Donnell (TEL), Michele Widdowson (MHL), Bronson McPherson (MHL), Sophie Diller (TEL), Charmaine Bennett (TEL), John Hudson (CMG), Theresa Lasiak (CEICC) and Tony Underwood (CEICC). The work reported herein was carried out at the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales, acting on behalf of the client. -

May—June 2015 President’S Report

Large & Small Feeder Sizes The BEST SLOW FEEDER Hay Bag on the Market! Quick & Super Easy to Fill Minimizes Hay Waste - Saves YOU Money Benefits Your Horse by Slow Feeding www.haymaximizer.com.au or P: 0429 99 55 96 Saddle Cloths are different…… Here’s Why ! High Density Pure Wool Knitted Fleece breathes, allowing the horse to perspire naturally, minimises heat build up & heat bumps! No edge binding A wide range of Saddle Ties to cause rubbing Designs / Styles standard available Knitted wool available in Natural, Silver & Girth Guides Charcoal standard D-Lua Park Pure Wool Saddle Cloths have no seams, are cut from one piece of material, are highly flexible to allow gap over the wither. Machine Washable in warm water , colours will not bleed. Long life is assured if adequately maintained. Shop Online Brook Sample, Web: www. d-luapark.com.au MultiTom Quilty Contact Winner , Uses & E: [email protected] Recommends P: (07) 54 644 222 %URRN6DPSOH D-Lua Park M: 0427 976 450 Saddle Cloths Contents Advertisers Articles and Results Dixon Smith Back Cover Dinka Dekaris Tumut Ride 53 D-Lua Park Inside Front Cover Homewood Ride Report 47 Muddy Creek Inside Back Cover Homewood Ride Results 50 Sun Tec Enterprises Inside Back Cover Bumbaldry Ride Results 35 Bumbaldry Ride Report 30 Williams Valley Ride Results 16 Reports & Notices Williams Valley Ride Report 13 Letter to Editor 42 Windeyer Ride Results 11 Meeting Report 16 January 2015 36 Windeyer Twilight Ride Report 8 Meeting Report 20 February 2015 57 Ilona Hudson 17 Meeting Report 7 February -

Berowra Waters Ferry Ramp Upgrade Review of Environmental Factors Roads and Maritime Services | July 2019

Berowra Waters Ferry Ramp Upgrade Review of Environmental Factors Roads and Maritime Services | July 2019 BLANK PAGE Berowra Waters Ferry Ramp Upgrade Review of Environmental Factors Roads and Maritime Services | July 2019 Prepared by NGH Environmental, Sure Environmental and Roads and Maritime Services Copyright: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of NSW Roads and Maritime Services. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of NSW Roads and Maritime Services constitutes an infringement of copyright. Document controls Approval and authorisation Title Berowra Waters Ferry Ramp Upgrade review of environmental factors Accepted on behalf of NSW Joshua Lewis Roads and Maritime Services Project Manager by: Signed: Dated: Executive summary The proposal The car ferry at Berowra Waters provides access between Berowra, Berowra Waters and Berrilee, in the far northern suburbs of Sydney. It is maintained and operated by Roads and Maritime Services NSW (Roads and Maritime). Roads and Maritime proposes to upgrade the ferry ramps at Berowra Waters with precast concrete panels for the sections below the tide level and poured in situ ramp sections above the high water mark. Need for the proposal The proposal is required to maintain a safe ingress and egress for pedestrians and vehicles approaching the ferry. Maintenance inspections indicate the existing ferry ramps are showing signs of degradation that could pose a safety hazard for pedestrians and vehicles. Without a safe operating ferry at Berowra Waters motorist travelling between Berrilee and Berowra would be required to detour via Galston, a detour of about 19 kilometres. -

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

Ted Freeman and the Battle for the Injured Brain: A

Ted Freeman and the Battle for the Injured Brain A case history of professional prejudice Peter McCullagh Ted Freeman and the Battle for the Injured Brain A case history of professional prejudice Peter McCullagh Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: McCullagh, Peter. Title: Ted Freeman and the battle for the injured brain : a case history of professional prejudice / Peter McCullagh. ISBN: 9781922144317 (paperback) 9781922144324 (ebook) Subjects: Freeman, E. A. (Edward Alan) Coma--Treatment. Coma--Patients--Rehabilitation. Brain damage--Treatment. Brain damage--Patients--Rehabilitation. Brain--Treatment. Brain--Wounds and injuries--Rehabilitation. Dewey Number: 616.8046 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover photograph courtesy of Dorothy Freeman. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Acronyms . ix Preface . xi Introduction . 1 1 . The origins of a commitment . 13 2 . Misdiagnosis: Patients’ stories . 33 3 . Families: No easy way forward . 59 4 . Emergence from coma after brain injury: Freeman’s contribution . 79 5 . What future after emergence? . 101 6 . Trials and tribulations . 125 7 . Concerted opposition in Australia . 147 8 . International support forthcoming . 175 9 . Some conclusions . 191 v Acknowledgments This book is intended to represent, in a small way, an acknowledgment of the achievements of people with brain injury and their families. -

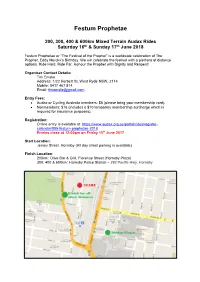

Festum Prophetae

Festum Prophetae 200, 300, 400 & 600km Mixed Terrain Audax Rides Saturday 16th & Sunday 17th June 2018 Festum Prophetae or "The Festival of the Prophet" is a worldwide celebration of The Prophet, Eddy Merckx's Birthday. We will celebrate the festival with a plethora of distance options. Ride Hard. Ride Far. Honour the Prophet with Dignity and Respect! Organiser Contact Details: Tim Emslie Address: 1/22 Herbert St, West Ryde NSW, 2114 Mobile: 0417 467 814 Email: [email protected] Entry Fees: • Audax or Cycling Australia members: $6 (please bring your membership card). • Nonmembers: $16 (includes a $10 temporary membership surcharge which is required for insurance purposes). Registration: Online entry is available at: https://www.audax.org.au/portal/rides/register- calendar/885-festum-prophetae-2018 Entries close at 12:00pm on Friday 15th June 2017 Start Location: Jersey Street, Hornsby (All day street parking is available) Finish Location: 200km: Olive Bar & Grill, Florence Street (Hornsby Plaza) 300, 400 & 600km: Hornsby Police Station – 292 Pacific Hwy, Hornsby Start Time: The ride starts at 6:00am sharp. Please arrive by 5:45am for admin and light check. Please arrive ready for the lighting and reflective vest inspection. Lighting: The maximum ride time for all rides is outside daylight hours, therefore Audax lighting rules do apply. Lighting rules can be viewed on the Audax website (follow the links below). There will be an inspection prior to commencing the ride. Lighting: http://audax.org.au/public/images/stories/Documents/lightingrequirements.pdf Reflective Vest: http://audax.org.au/public/images/stories/Documents/reflectivegarments.pdf Food/water: This ride is unsupported however food and water is readily available along the route and at the control locations. -

Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Regional Flood Study

INFRASTRUCTURE NSW HAWKESBURY-NEPEAN VALLEY REGIONAL FLOOD STUDY FINAL REPORT VOLUME 1 – MAIN REPORT JULY 2019 HAWKESBURY-NEPEAN VALLEY REGIONAL FLOOD STUDY Level 2, 160 Clarence Street FINAL REPORT Sydney, NSW, 2000 Tel: (02) 9299 2855 Fax: (02) 9262 6208 Email: [email protected] 26 JULY 2019 Web: www.wmawater.com.au Project Project Number Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Regional Flood Study 113031-07 Client Client’s Representative Infrastructure NSW Sue Ribbons Authors Prepared by Mark Babister MER Monique Retallick Mikayla Ward Scott Podger Date Verified by 26 Jul 2019 MKB Revision Description Distribution Date 7 Final Report Public release Jul 2019 Final Draft Infrastructure NSW, local councils, Jan 2019 6 state agencies, utilities, ICA 5 Final Draft for Client Review Infrastructure NSW Oct 2018 Infrastructure NSW, local councils, 4 Final Draft for External Review state agencies, independent technical Sep 2018 review 3 Revised Draft Infrastructure NSW Jul 2018 2 Preliminary Draft Infrastructure NSW May 2018 1 Working Draft WMAwater Jul 2017 COPYRIGHT NOTICE Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Regional Flood Study © State of New South Wales 2019 ISBN 978-0-6480367-0-8 Infrastructure NSW commissioned WMAwater Pty Ltd to develop this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Infrastructure NSW shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. -

Yananda Yoga and Meditation Retreat

Relax and Renew Yoga and Meditation Retreat October 12th -15th 2020 Taking time out is vital to our life, health and longevity. A few days away to unwind, relax and restore your inner balance. Unplug from the pressures of life and daily routine. Yanada is a beautiful tranquil location just two hours out of Sydney. A perfect location to restore, relax and restore body and mind, connect more deeply with yourself and nature. Your retreat will include: All meals and accomodation. Meditation and Yoga: 2 hr sunrise and sunset yoga and meditation energy balancing meridian yoga healing, balancing and restoring, calming and relaxing nourishing mind, body and soul. Reflection Enjoy ample time reconnecting with yourself and nature. Nourish yourself with rest, yoga, healthy food, nature and time out. Medicine for mind and body. Where: Yanada is a beautiful six bedroom property set on 38 acres in Darkinjung country, nestled between the McDonald River and the Yengo Mountains. 2km outside the historic village of St Albans and 17 km from Wiseman's Ferry and the Hawkesbury River. The setting is remote and idyllic with complete privacy assured; you will unwind as soon as you enter the driveway. Take a deep breath... And arrive ૐ Yanada is a convenient 90 minutes’ drive from Sydney CBD, located in the McDonald Valley 2km outside the historic village of St Albans. Adjoining Yengo National Park and are 17 minutes from Wiseman's Ferry and the Hawkesbury River. This is the southern tip of Darkinjung country with Mount Yengo at its heart. This place is hidden and remote, known since first European settlement as the Forgotten Valley, yet less than 2 hours’ drive from Sydney. -

Act One: Scene One the Build-Up and the Breakaway

Act One: Scene One The Build-up and the Breakaway It was late afternoon on Sunday, March 19, 1978, and Garry McCully was in his office at Colo Shire Council. It had been raining steadily and heavily for the past three days. So far it had bucketed down 350 mm, and it looked pretty certain that the river was in for another big flood. The Shire Clerk, Garry’s immediate boss, was out of town and Garry was in the decision-making hotseat. Earlier that day there had been reports of consider- able storm damage in the Macdonald Valley so Garry sent Jim Larkin, a Council Overseer, to check out the situation there. At this stage the advice from the Bureau of Meteorology was that minor flooding would develop along the Nepean River in the Cam- den district, and that the Nepean at Camden was expected to reach a height of 6.8 metres by 8pm that evening and 9 metres by 3 the next morning. At half past seven Garry rang the Weather Bureau again and spoke to John North, seeking further weather information that might help him make a decision about the ferries. He didn’t want to have the ferries taken off their cables at night if it could be avoided. It would be more difficult and more dangerous. North confirmed the earlier forecast of probable minor flooding the next day, though this could happen earlier, he said, if there were sustained heavy falls that night. Normally it takes about 150 mm of rain to cause a flood on the Hawkesbury, depending on prevailing conditions and what’s falling in the catchments of the Macdonald and Colo and Grose Rivers, and from the way it had been raining it looked like the bridge at Windsor would be under water by midnight. -

Dates for Your Diary Folk News Dance News CD Reviews Folk

Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Dates For Your Diary Folk News Issue No 396 Dance News JUNE 2008 $3.00 CD Reviews 8 al 200 stiv k Fe ol s F an Alb t St p Contender a s Cu horu - C op Arch Bish ♫ Folk music ♫ dance ♫ festivals ♫ reviews ♫ profiles ♫ diary dates ♫ sessionsThe Folk Federation ONLINE♫ teachers - jam.org.au ♫ opportunitiesThe CORNSTALK Gazette JUNE 2008 1 If your important item misses Cornstalk, please remember there are also:folkmail (members’ email list) contact Julie Bishop JUNE 2008 (02 9524 0247) [email protected]. In this issue Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc au jam.org.au –Folk Fed website, here Post Office Box A182 Dates for your diary p4 members can post info, articles, etc. Sydney South NSW 1235 Festivals, workshops, schools p6 ISSN 0818 7339 ABN9411575922 Advertising Rates www.jam.org.au Passion for finding folklore (Edgar Size mm Members Non-mem Waters 26-10-26 - 1-5-08 p8) Editor, Cornstalk - Coral Vorbach Full page 180x250 $80 $120 Looking Back - p10 Post Office Box 5195 1/2 page 180x125 $40 $70 Arlo Guthrie p11 Cobargo NSW 2550 St Albans Folk Festival 2008 p12 Tel/Fax: 02 6493 6758 1/4 page 90x60 $25 $50 [email protected] 1/8 page 45 x 30 $15 $35 CD reviews p14 Cornstalk is the official publication of the Folk Back cover 180x250 $100 $150 Federation of NSW. 2 + issues per mth $90 $130 DEADLINE JULY Adverts - 5th June, Contributions, news, reviews, poems, photographs Copy - 10th June Advertising artwork required by 5th Friday of most welcome.