Skill Selectivity in Transatlantic Migration: the Case of Canary Islanders in Cuba*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

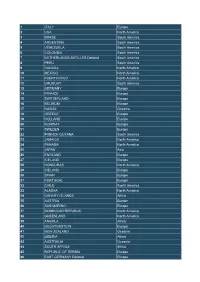

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1 Louisiana Historical Background 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 •Spain sides with France in the now expanded Seven Years War •The Treaty of Fontainebleau was a secret agreement of 1762 in which France ceded Louisiana (New France) to Spain. •Spain acquires Louisiana Territory from France 1763 •No troops or officials for several years •The colonists in western Louisiana did not accept the transition, and expelled the first Spanish governor in the Rebellion of 1768. Alejandro O'Reilly suppressed the rebellion and formally raised the Spanish flag in 1769. Antonio de Ulloa Alejandro O'Reilly 1763 – 1770 1763 – 1770 •France’s secret treaty contained provisions to acquire the western Louisiana from Spain in the future. •Spain didn’t really have much interest since there wasn’t any precious metal compared to the rest of the South America and Louisiana was a financial burden to the French for so long. •British obtains all of Florida, including areas north of Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Maurepas and Bayou Manchac. •British built star-shaped sixgun fort, built in 1764, to guard the northern side of Bayou Manchac. •Bayou Manchac was an alternate route to Baton Rouge from the Gulf bypassing French controlled New Orleans. •After Britain acquired eastern Louisiana, by 1770, Spain became weary of the British encroaching upon it’s new territory west of the Mississippi. •Spain needed a way to populate it’s new territory and defend it. •Since Spain was allied with France, and because of the Treaty of Allegiance in 1778, Spain found itself allied with the Americans during their independence. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

1 Centro Vasco New York

12 THE BASQUES OF NEW YORK: A Cosmopolitan Experience Gloria Totoricagüena With the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre TOTORICAGÜENA, Gloria The Basques of New York : a cosmopolitan experience / Gloria Totoricagüena ; with the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre. – 1ª ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2003 p. ; cm. – (Urazandi ; 12) ISBN 84-457-2012-0 1. Vascos-Nueva York. I. Sarriugarte Doyaga, Emilia. II. Renteria Aguirre, Anna M. III. Euskadi. Presidencia. IV. Título. V. Serie 9(1.460.15:747 Nueva York) Edición: 1.a junio 2003 Tirada: 750 ejemplares © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Presidencia del Gobierno Director de la colección: Josu Legarreta Bilbao Internet: www.euskadi.net Edita: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia - Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 - 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Diseño: Canaldirecto Fotocomposición: Elkar, S.COOP. Larrondo Beheko Etorbidea, Edif. 4 – 48180 LOIU (Bizkaia) Impresión: Elkar, S.COOP. ISBN: 84-457-2012-0 84-457-1914-9 D.L.: BI-1626/03 Nota: El Departamento editor de esta publicación no se responsabiliza de las opiniones vertidas a lo largo de las páginas de esta colección Index Aurkezpena / Presentation............................................................................... 10 Hitzaurrea / Preface......................................................................................... -

Arachne@Rutgers: Journal of Iberian and Latin American Literary And

Arachne@Rutgers Journal of Iberian and Latin American Literary and Cultural Studies, Volume 2, Issue 1 (2002) The Role of the City in the Formation of Spanish American Dialect Zones © John M. Lipski The Pennsylvania State University E-mail - [email protected] 1. Introduction Five hundred years ago, a rather homogeneous variety of Spanish spoken by a few thousand settlers was scattered across two continents. Although many regional languages were spoken in fifteenth century Spain (and most are still spoken even today), only Castilian made its way to the Americas, in itself a remarkable development. More remarkable still is the regional and social variation that characterizes modern Latin American Spanish; some of the differences among Latin American Spanish dialects are reflected in dialect divisions in contemporary Spain, while others are unprecedented across the Atlantic. Some practical examples of this diversity are: At least in some part of every Latin American nation except for Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, the pronoun vos is used instead of or in competition with tú for familiar usage; at least six different sets of verbal endings accompany voseo usage. The pronoun vos is not used in any variety of Peninsular Spanish, nor has it been used for more than three hundred years. In the Caribbean, much of Central America, the entire Pacific coast of South America, the Rio de la Plata nations, and a few areas of Mexico, syllable and word-final consonants are weakened or lost, especially final [s]. In interior highland areas of Mexico, Guatemala, and the Andean zone of South America, final consonants are tenaciously retained, while unstressed vowels are often lost, thus making quinientas personas sound like quinients prsons. -

CAJUNS, CREOLES, PIRATES and PLANTERS Your New Louisiana Ancestors Format Volume 1, Number 18

CAJUNS, CREOLES, PIRATES AND PLANTERS Your New Louisiana Ancestors Format Volume 1, Number 18 By Damon Veach SIG MEETING: Le Comité des Archives de la Louisiane’s African American Special Interest Group (SIG) will hold a meeting on July 25th, from 9:00 to 11:30 a.m. at the Delta Sigma Theta Life Development Center located at 688 Harding Blvd., next to Subway. The meeting is free and open to the public. Ryan Seidemann, President of the Mid City Historical Cemetery Coalition in Baton Rouge, will speak on Sweet Olive Cemetery. Officially dating back to 1898, Sweet Olive was the first cemetery for blacks incorporated in the Baton Rouge city limits. Burials are, however, believed to have occurred prior to 1898. Members of the group will give short presentations on a variety of African American genealogy topics. Cherryl Forbes Montgomery will discuss how to use Father Hebert’s Southwest Louisiana Records effectively. Barbara Shepherd Dunn will describe how she identified and documented the slave owners of her great grandmother. And, Judy Riffel will speak on the SIG’s efforts to create an East Baton Rouge Parish slave database. Time will be allowed at the end of the program for attendees to share their own genealogical problems and successes and to ask questions. With nearly 600 members, Le Comité is one of the largest genealogical groups in the state today. Its African American Genealogy SIG was formed in 2006 to help people doing African American research in Louisiana have a place to communicate and help one another. The group currently consists of 24 Le Comité members who have begun holding meetings and seminars. -

Prejudices in Spain

Prejudices in Spain Index ❏ Photo of the communities ❏ Andalusia ❏ Basque Country ❏ Galicia ❏ Canary Islands ❏ Catalonia ❏ Spain’s mainland from the point of view of Canarians Photo of the communities Andalusia It’s located in the south of the Iberian peninsula and the political capital is Sevilla. It’s the most populated autonomous community of Spain. Andalusia The Andalusians have a reputation for always being partying and making others laugh. When they talk about things they tend to distort reality, increasing it. People from Spain usually think that Andalusian people are lazy. They usually are hospitable, religious, superstitious and generous. Basque Country The Basque Country is an autonomous community in northern Spain. The political capital is Vitoria. Of the Basques there are two generalized prejudices, that they all are separatist and tough people. They are hard, frank, robust, lovers of their land, separatists, gross and they never laugh. A possible explanation for this, if it is true, is that traditional Basque sports stand out for being very physical, for the need to use quite a lot of force. On the other hand, the fact that they are separatists comes from political issues due to the nationalist thoughts of a part of the population. Galicia Galicia is an autonomous community of Spain and historic nationality under Spanish law. It’s Located in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. The political capital is Santiago de Compostela, in the province of A Coruña. Galicians are considered closed, distrustful, indecisive, superstitious and traditionalists. Canary Islands The Canary Islands is a Spanish archipelago and the southernmost autonomous community of Spain located in the Atlantic Ocean, 100 kilometres west of Morocco at the closest point. -

Hispanic Texans

texas historical commission Hispanic texans Journey from e mpire to Democracy a GuiDe for h eritaGe travelers Hispanic, spanisH, spanisH american, mexican, mexican american, mexicano, Latino, Chicano, tejano— all have been valid terms for Texans who traced their roots to the Iberian Peninsula or Mexico. In the last 50 years, cultural identity has become even more complicated. The arrival of Cubans in the early 1960s, Puerto Ricans in the 1970s, and Central Americans in the 1980s has made for increasing diversity of the state’s Hispanic, or Latino, population. However, the Mexican branch of the Hispanic family, combining Native, European, and African elements, has left the deepest imprint on the Lone Star State. The state’s name—pronounced Tay-hahs in Spanish— derives from the old Spanish spelling of a Caddo word for friend. Since the state was named Tejas by the Spaniards, it’s not surprising that many of its most important geographic features and locations also have Spanish names. Major Texas waterways from the Sabine River to the Rio Grande were named, or renamed, by Spanish explorers and Franciscan missionaries. Although the story of Texas stretches back millennia into prehistory, its history begins with the arrival of Spanish in the last 50 years, conquistadors in the early 16th cultural identity century. Cabeza de Vaca and his has become even companions in the 1520s and more complicated. 1530s were followed by the expeditions of Coronado and De Soto in the early 1540s. In 1598, Juan de Oñate, on his way to conquer the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, crossed the Rio Grande in the El Paso area. -

Spanish and Acadians

ACADIANS AND SPANISH COMING TOGETHER Disclaimer Even though this work seems to be a lot, it is far from being complete. Some of the dates have been proven, but not all. This work is ongoing and will be sourced as time goes by. Should the recipient find errors or wish to expand on this information, please do so and let me know what changes have been made, from there, I will make the corrections or add the information to my database. I encourage all who may come across this work, to continue doing their own research. I am not responsible for errors or any additions you may add. It is a labor of love and it always has been my intention to find all of my ancestors and cousins , no matter who and where they exist, living or deceased. It is a process that may never end, so get on board and enjoy your visit with the old folks. Rogers Romero Acadian Timeline o Acadians had been in Acadie from 1604 to deportation o Landed at St. Croix Island in 1604 then moved to Port Royal in 1605 due to famine on the Island o Most Acadian’s were deported in 1755, but not all of them were deported because some saw the writing on the wall and headed to the woods until they had to give up in about 1759 o Joseph Broussard dit Beausoleil, due to an agreement he made with the British, led the group that was to be imprisoned, to Fort Cumberland (old Fort Beausejour) o Fort Cumberland, then were transported to Georges Island, off the coast of Halifax, Nova Scotia later in 1760 o French King cedes the Louisiana territory to his cousin, the Spanish King, due to depleted -

Peer Review Report

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Directorate for Education Education Management and Infrastructure Division Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education (IMHE) Supporting the contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Peer Review Report Canary Islands, Spain Chris Duke, Francisco Marmolejo, Jose Ginés Mora, Walter Uegama July 2006 The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the OECD or its member countries. 1 This Peer Review Report is based on the review visit to the Canaries in April 2006, the regional Self- Evaluation Report, and other background material. As a result, the report reflects the situation up to that period. The preparation and completion of this report would not have been possible without the support of very many people and organisations. OECD/IMHE and the Peer Review Team for the Canaries wish to acknowledge the substantial contribution of the region, particularly through its Coordinator, the authors of the Self-Evaluation Report, and its Regional Steering Group. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE......................................................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................7 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS....................................................................................12 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................13 -

Unit 3: Exploration and Early Colonization (Part 2)

Unit 3: Exploration and Early Colonization (Part 2) Spanish Colonial Era 1700-1821 For these notes – you write the slides with the red titles!!! Goals of the Spanish Mission System To control the borderlands Mission System Goal Goal Goal Represent Convert American Protect Borders Spanish govern- Indians there to ment there Catholicism Four types of Spanish settlements missions, presidios, towns, ranchos Spanish Settlement Four Major Types of Spanish Settlement: 1. Missions – Religious communities 2. Presidios – Military bases 3. Towns – Small villages with farmers and merchants 4. Ranchos - Ranches Mission System • Missions - Spain’s primary method of colonizing, were expected to be self-supporting. • The first missions were established in the El Paso area, then East Texas and finally in the San Antonio area. • Missions were used to convert the American Indians to the Catholic faith and make loyal subjects to Spain. Missions Missions Mission System • Presidios - To protect the missions, presidios were established. • A presidio is a military base. Soldiers in these bases were generally responsible for protecting several missions. Mission System • Towns – towns and settlements were built near the missions and colonists were brought in for colonies to grow and survive. • The first group of colonists to establish a community was the Canary Islanders in San Antonio (1730). Mission System • Ranches – ranching was more conducive to where missions and settlements were thriving (San Antonio). • Cattle were easier to raise and protect as compared to farming. Pueblo Revolt • In the late 1600’s, the Spanish began building missions just south of the Rio Grande. • They also built missions among the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico. -

The Spanish of the Canary Islands

THE SPANISH OF THE CANARY ISLANDS An indisputable influence in the formation of Latin American Spanish, often overshadowed by discussion of the `Andalusian' contribution, is the Canary Islands. Beginning with the first voyage of Columbus, the Canary Islands were an obligatory way-station for Spanish ships sailing to the Americas, which often stayed in the islands for several weeks for refitting and boarding of provisions. Canary Islanders also participated actively in the settlement and development of Spanish America. The Canary Islands merit a bizarre entry in the history of European geography, since the islands were well known to ancient navigators, only to pass into oblivion by the Middle Ages. After the early descriptions of Pliny and other writers of the time, more than a thousand years were to pass before the Canary Islands were mentioned in European texts, although contact between the indigenous Guanches and the nearby north African coast continued uninterrupted. Spain colonized the Canary Islands beginning in 1483, and by the time of Columbus's voyages to the New World, the Canary Islands were firmly under Spanish control. The indigenous Guanche language disappeared shortly after the Spanish conquest of the islands, but left a legacy of scores of place names, and some regional words. From the outset, the Canaries were regarded as an outpost rather than a stable colony, and the islands' livlihood revolved around maritime trade. Although some islanders turned to farming, particularly in the fertile western islands, more turned to the sea, as fishermen and sailors. With Columbus's discoveries, the Canary Islands became obligatory stopover points en route to the New World, and much of the islands' production was dedicated to resupplying passing ships.