The Medical Resources and Practice of the Crusader States in Syria and Palestine 1096-1193

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample File Under Licence

THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK B CREDITS LINE DEVELOPER: Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan WRITING: Darren Pearce and Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan ADDITIONAL DEVELOPMENT: Nathaniel Torson EDITING: Dominic McDowall-Thomas COVER: Paul Bourne GRAPHIC DESIGN AND LAYOUT: Paul Bourne CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Dominic McDowall-Thomas ART DIRECTOR: Jon Hodgson SPECIAL THANKS: Georgie Britton and the BBC Team for all their help. “My First Begins With An Unearthly Child” The First Doctor Sourcebook is published by Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd (UK reg. no.6036414). Find out more about us and our games at www.cubicle7.co.uk © Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd. 2013 BBC, DOCTOR WHO (word marks, logos and devices), TARDIS, DALEKS, CYBERMAN and K-9 (wordmarks and devices) are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used Sample file under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996. Doctor Who logo © BBC 2009. TARDIS image © BBC 1963. Dalek image © BBC/Terry Nation 1963.Cyberman image © BBC/Kit Pedler/Gerry Davis 1966. K-9 image © BBC/Bob Baker/Dave Martin 1977. Printed in the USA THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK B CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE 4 CHAPTER SEVEN 89 Introduction 5 The Chase 90 Playing in the First Doctor Era 6 The Time Meddler 96 The Tardis 12 Galaxy Four 100 CHAPER TWO 14 CHAPTER EIGHT 104 An Unearthly Child 15 The Myth Makers 105 The Daleks 20 The Dalek’s Master Plan 109 The Edge of Destruction 26 The Massacre 121 CHAPTER THREE 28 CHAPTER NINE 123 Marco Polo 29 The Ark 124 The Keys of Marinus 35 The Celestial Toymaker 128 The -

Women in the Crusader States: the Queens of Jerusalem (1100-1190)

WOMEN IN THE CRUSADER STATES: THE QUEENS OF JERUSALEM (1100-1190) by BERNARD HAMILTON HE important part played by women in the history of the crusader states has been obscured by their exclusion from the Tbattle-field. Since scarcely a year passed in the Frankish east which was free from some major military campaign it is natural that the interest of historians should hâve centred on the men responsible for the defence of the kingdom. Yet in any society at war considérable power has to be delegated to women while their menfolk are on active service, and the crusader states were no exception to this gênerai rule. Moreover, because the survival rate among girl-children born to Frankish settlers was higher than that among boys, women often provided continuity to the society of Outremer, by inheriting their fathers' fiefs and transmitting them to husbands many of whom came from the west. The queens of Jérusalem are the best documented group of women in the Frankish east and form an obvious starting-point for any study of the rôle of women there. There is abundant évidence for most of them in a wide range of sources, comprising not only crusader chronicles and documents, but also western, Byzantine, Syriac and Armenian writers. Arab sources very seldom mentioned them : the moslem world was clearly shocked by the degree of social freedom which western women enjoyed1 and reacted to women with political power much as misogynist dons did to the first génération of women undergraduates, by affecting not to notice them. Despite the fulness of the évidence there is, so far as I am aware, no detailed study of any of the twelfth century queens of Jérusalem with the notable exception of Mayer's article on Melisende.2 For reasons of brevity only the queens of the first kingdom will be considered hère. -

Citadel of Masyaf

GUIDEBOOK English version TheThe CCitadelitadel ofof MMasyafasyaf Description, History, Site Plan & Visitor Tour Description, History, Site Plan & Visitor Tour Frontispiece: The Arabic inscription above the basalt lintel of the monumental doorway into the palace in the Inner Castle. This The inscription is dated to 1226 AD, and lists the names of “Alaa ad-Dunia of wa ad-Din Muhammad, Citadel son of Hasan, son of Muhammad, son of Hasan (may Allah grant him eternal power); under the rule of Lord Kamal ad- Dunia wa ad-Din al-Hasan, son of Masa’ud (may Allah extend his power)”. Masyaf Opposite: Detail of this inscription. Text by Haytham Hasan The Aga Khan Trust for Culture is publishing this guidebook in cooperation with the Syrian Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums as part of a programme for the Contents revitalisation of the Citadel of Masyaf. Introduction 5 The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Geneva, Switzerland (www.akdn.org) History 7 © 2008 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher. Printed in Syria. Site Plan 24 Visitor Tour 26 ISBN: 978-2-940212-06-4 Introduction The Citadel of Masyaf Located in central-western Syria, the town of Masyaf nestles on an eastern slope of the Syrian coastal mountains, 500 metres above sea level and 45 kilometres from the city of Hama. Seasonal streams flow to the north and south of the city and continue down to join the Sarout River, a tributary of the Orontes. -

Cry Havoc Règles Fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page1

ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page1 HISTORY & SCENARIOS ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page2 © Buxeria & Historic’One éditions - 2017 - v1.0 ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page3 SELJUK SULTANATE OF RUM Konya COUNTY OF EDESSA Sis PRINCIPALITY OF ARMENIAN CILICIA Edessa Tarsus Turbessel Harran BYZANTINE EMPIRE Antioch Aleppo PRINCIPALITY OF ANTIOCH Emirate of Shaïzar Isma'ili COUNTY OF GRAND SELJUK TRIPOLI EMPIRE Damascus Acre DAMASCUS F THE MIDDLE EAST KINGDOM IN 1135 TE O OF between the First JERUSALEM and Second Crusades Jerusalem EMIRA N EW S FATIMID 0 150 km CALIPHATE ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:43 Page1 History The Normans in Northern Syria in the 12th Century 1. Historical background Three Normans distinguished themselVes during the First Crusade: Robert Curthose, Duke of NormandY and eldest son of William the Conqueror 1 Whose actions Were decisiVe at the battle of DorYlea in 1197, Bohemond of Taranto, the eldest son of Robert Guiscard 2, and his nepheW Tancred, Who led one of the assaults upon the Walls of Jerusalem in 1099. Before participating in the crusade, Bohemond had been passed oVer bY his Younger half-brother Roger Borsa as Duke of Puglia and Calabria on the death of his father in 1085. Far from being motiVated bY religious sentiment like GodfreY of Bouillon, the crusade Was for him just another occasion to Wage War against his perennial enemY, BYZantium, and to carVe out his oWn state in the HolY Land. -

VOLUME LXVI July 2020 NUMBER 7

VOLUME LXVI July 2020 NUMBER 7 VOLUME LXVI JULY 2020 NUMBER 7 Published monthly as an official publication of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar of the United States of America. Jeffrey N. Nelson Grand Master Jeffrey A. Bolstad Contents Grand Captain General and Publisher 325 Trestle Lane Grand Master’s Message Lewistown, MT 59457 Grand Master Jeffrey N. Nelson ..................... 4 Address changes or corrections William of Tyre Chronicler of the Crusaders and all membership activity and Kingdom of Jerusalem including deaths should be re- Sir Knight George L. Marshall, Jr., PGC ............. 8 ported to the recorder of the lo- cal Commandery. Please do not The Lost Memento Mori report them to the editor. of the Knights Templar Sir Knight Matthew J. Echevarria................... 21 Lawrence E. Tucker Grand Recorder Freemasonry and the Grand Encampment Office Medieval Craft Guilds 5909 West Loop South, Suite 495 Sir Knight Jaime Paul Lamb ........................... 25 Bellaire, TX 77401-2402 Phone: (713) 349-8700 What is Masonry? Fax: (713) 349-8710 Sir Knight Robert Bruneau ............................ 29 E-mail: [email protected] Magazine materials and correspon- dence to the editor should be sent in elec- tronic form to the managing editor whose Features contact information is shown below. Materials and correspondence concern- In Memoriam ......................................................... 5 ing the Grand Commandery state supple- ments should be sent to the respective Prelate’s Apartment ............................................... 6 supplement editor. Knightly News John L. Palmer Membership Patents are now Available ................ 15 Managing Editor Post Office Box 566 Foccus on Chivalry ................................................ 16 Nolensville, TN 37135-0566 The Knights Templar Eye Foundation ................17,20 Phone: (615) 283-8477 Fax: (615) 283-8476 Grand Commandery Supplement ......................... -

The 12Th Century Seismic Paroxysm in the Middle East: a Historical Perspective

ANNALS OF GEOPHYSICS, VOL. 47, N. 2/3, April/June 2004 The 12th century seismic paroxysm in the Middle East: a historical perspective Nicholas N. Ambraseys Department of Civil Engineering, Imperial College, London, U.K. Abstract The Dead Sea Fault and its junction with the southern segment of the East Anatolian fault zone, despite their high tectonic activity have been relatively quiescent in the last two centuries. Historical evidence, however, shows that in the 12th century these faults ruptured producing the large earthquakes of 1114, 1138, 1157 and 1170. This paroxysm occurred during one of the best-documented periods for which we have both Occidental and Arab chronicles, and shows that the activity of the 20th century, which is low, is definitely not a reliable guide to the activity over a longer period. The article is written for this Workshop Proceedings with the ar- chaeoseismologist, and in particular with the seismophile historian in mind. It aims primarily at putting on record what is known about the seismicity of the region in the 12th century, describe the problems associated with the interpretation of macroseismic data, their limitations and misuse, and assess their completeness, rather than an- swer in detail questions regarding the tectonics and seismic hazard of the region, which will be dealt with else- where on a regional basis. Key words Middle East – 12th century – historical tive effects derived from historical sources can earthquakes be reliably quantified. The assessment of an historical earthquake requires the documentary information to be re- 1. Introduction viewed with reference to the environmental conditions and historical factors that have in- The purpose of this article is to present the fluenced the reporting of the event. -

History, Hollywood, and the Crusades

HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD, AND THE CRUSADES ________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston ________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts _______________ By Mary R. McCarthy May, 2013 HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD, AND THE CRUSADES ________________ An Abstract of a Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston ________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts _______________ By Mary R. McCarthy May, 2013 HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD, AND THE CRUSADES ______________________ Mary R. McCarthy APPROVED: ______________________ Sally N. Vaughn, Ph.D. Committee Chair ______________________ Martin Melosi, Ph.D. ______________________ Lorraine Stock, Ph.D. _______________________ John W. Roberts, Ph.D. Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of English ABSTRACT This thesis discusses the relationship between film and history in the depiction of the Crusades. It proposes that film is a valuable historical tool for teaching about the past on several levels, namely the film’s contemporaneous views of the Crusades, and the history Crusades themselves. This thesis recommends that a more rigid methodology be adopted for evaluating the historicity of films and encourages historians to view films not only as historians but also as film scholars. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my history teachers and professors over the years who inspired me to do what I love. In particular I am indebted to Mimi Kellogg and my thesis committee: Dr. Sally Vaughn, Dr. Martin Melosi, and Dr. Lorraine Stock. I am also indebted to my friends and family for their support and enthusiasm over the past few months. -

The Historical Earthquakes of Syria: an Analysis of Large and Moderate Earthquakes from 1365 B.C

ANNALS OF GEOPHYSICS, VOL. 48, N. 3, June 2005 The historical earthquakes of Syria: an analysis of large and moderate earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D. Mohamed Reda Sbeinati (1), Ryad Darawcheh (1) and Mikhail Mouty (2) (1) Department of Geology, Atomic Energy Commission of Syria, Damascus, Syria (2) Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, Damascus University, Damascus, Syria Abstract The historical sources of large and moderate earthquakes, earthquake catalogues and monographs exist in many depositories in Syria and European centers. They have been studied, and the detailed review and analysis re- sulted in a catalogue with 181 historical earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D. Numerous original documents in Arabic, Latin, Byzantine and Assyrian allowed us to identify seismic events not mentioned in previous works. In particular, detailed descriptions of damage in Arabic sources provided quantitative information necessary to re-evaluate past seismic events. These large earthquakes (I0>VIII) caused considerable damage in cities, towns and villages located along the northern section of the Dead Sea fault system. Fewer large events also occurred along the Palmyra, Ar-Rassafeh and the Euphrates faults in Eastern Syria. Descriptions in original sources doc- ument foreshocks, aftershocks, fault ruptures, liquefaction, landslides, tsunamis, fires and other damages. We present here an updated historical catalogue of 181 historical earthquakes distributed in 4 categories regarding the originality and other considerations, we also present a table of the parametric catalogue of 36 historical earth- quakes (table I) and a table of the complete list of all historical earthquakes (181 events) with the affected lo- cality names and parameters of information quality and completeness (table II) using methods already applied in other regions (Italy, England, Iran, Russia) with a completeness test using EMS-92. -

Die Welt Des Islam Die Welt Des Islam Aus Westlich Demokratischer Sicht

251 / JULI 2003 (SONDERDRUCK) 43. JAHRGANG Die Welt des Islam Die Welt des Islam aus westlich demokratischer Sicht Sonderdruck mit Beiträgen aus der Verbandszeitschrift AUFTRAG Nr. 240 / Sep 2000 bis 250 / April 2003 der Gemeinschaft Katholischer Soldaten (GKS) und weiteren aktuellen Artikeln zum Thema Zusammengestellt und bearbeitet von Paul Schulz und Klaus Brandt Herausgegeben von der Gemeinschaft Katholischer Soldaten – GKS Redaktion, Bildbearbeitung und Druckvorstufe: Paul Schulz Druck: Köllen Druck und Verlag, Bonn © 2003 Gemeinschaft Katholischer Soldaten – GKS Inhaltsverzeichnis 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort.........................................................................................13 I. DIE GRUNDLAGEN DES ISLAM. EIN BEITRAG ZUR LEHRE MOHAMMEDS von Volker W. Böhler .........................15 1. Vorbemerkungen ....................................................................16 2. Der Islam, die „Hingabe an Gott“ ..........................................16 3. Die Koranische Lehre ............................................................17 3.1 Der Koran ......................................................................... 17 3.2 Die Glaubensgebote des Islam .......................................... 18 3.3 Die Säulen des Islam ........................................................ 19 3.4. Sunna und Hadithe ........................................................... 19 3.5. Die Scharia ....................................................................... 20 4. Hauptrichtungen ....................................................................20 -

Settlement on Lusignan Cyprus After the Latin Conquest: the Accounts of Cypriot and Other Chronicles and the Wider Context

perspektywy kultury / Varia perspectives on culture No. 33 (2/2021) Nicholas Coureas http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8903-8459 Cyprus Research Centre in Nicosia [email protected] DOI: 10.35765/pk.2021.3302.12 Settlement on Lusignan Cyprus after the Latin Conquest: The Accounts of Cypriot and other Chronicles and the Wider Context ABSTRACT The accounts of various chronicles of the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries on settlement in Cyprus in the years following the Latin conquest, from the end of the twelfth to the early thirteenth century, will be examined and com- pared. The details provided by the chronicles, where the information given derived from, the biases present in the various accounts, the extent to which they are accurate, especially in cases where they are corroborated or refuted by documentary evidence, will all be discussed. The chronicles that will be referred to are the thirteenth century continuation of William of Tyre, that provides the fullest account of the settlement of Latin Christians and others on Cyprus after the Latin conquest, the fifteenth century chronicle of Leon- tios Makhairas, the anonymous chronicle of “Amadi” that is probably date- able to the early sixteenth century although for the section on thirteenth cen- tury Cypriot history it draws on earlier sources and the later sixteenth century chronicle of Florio Bustron. Furthermore, the Chorograffia and Description of Stephen de Lusignan, two chronicles postdating the conquest of Cyprus by the Ottoman Turks in 1570, will also be referred to on the subject of settle- ment in thirteenth century Cyprus. By way of comparison, the final part of the paper examines the extent to which the evidence of settlement in other Medi- terranean lands derives chiefly from chronicles or from documentary sources. -

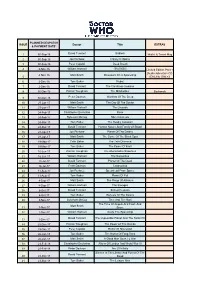

Issue Planned Despatch & Payment Date

PLANNED DESPATCH ISSUE Doctor Title EXTRAS & PAYMENT DATE* 1 30-Sep-16 David Tennant Gridlock Wallet & Travel Mug 2 30-Sep-16 Jon Pertwee Colony In Space 3 30-Sep-16 Peter Capaldi Deep Breath 4 4-Nov-16 William Hartnell 100,000BC Limited Edition Print + [Audio Adventure CD 4-Nov-16 Matt Smith Dinosaurs On A Spaceship 5 (ONLINE ONLY)] 6 2-Dec-16 Tom Baker Robot 7 2-Dec-16 David Tennant The Christmas Invasion 8 30-Dec-16 Patrick Troughton The Mindrobber Bookends 9 30-Dec-16 Peter Davison Warriors Of The Deep 10 27-Jan-17 Matt Smith The Day Of The Doctor 11 27-Jan-17 William Hartnell The Crusade 12 24-Feb-17 Christopher Eccleston Rose 13 24-Feb-17 Sylvester McCoy Silver Nemesis 14 24-Mar-17 Tom Baker The Deadly Assassin 15 24-Mar-17 David Tennant Human Nature And Family Of Blood 16 21-Apr-17 Jon Pertwee Planet Of The Daleks 17 21-Apr-17 Matt Smith The Curse Of The Black Spot 18 19-May-17 Colin Baker The Twin Dilemma 19 19-May-17 Tom Baker The Power Of Kroll 20 16-Jun-17 Patrick Troughton The Abominable Snowmen 21 16-Jun-17 William Hartnell The Sensorites 22 14-Jul-17 David Tennant Planet Of The Dead 23 14-Jul-17 Peter Davison Castrovalva 24 11-Aug-17 Jon Pertwee Spearhead From Space 25 11-Aug-17 Tom Baker Planet Of Evil 26 8-Sep-17 Matt Smith The Rings Of Akhaten 27 8-Sep-17 William Hartnell The Savages 28 6-Oct-17 David Tennant School Reunion 29 6-Oct-17 Tom Baker Genesis Of The Daleks 30 3-Nov-17 Sylvester McCoy Time And The Rani The Time Of Angels And Flesh And Matt Smith 31 3-Nov-17 Stone 32 1-Dec-17 William Hartnell Inside The Spaceship -

''Doctor Who'' - the First Doctor Episode Guide Contents

''Doctor Who'' - The First Doctor Episode Guide Contents 1 Season 1 1 1.1 An Unearthly Child .......................................... 1 1.1.1 Plot .............................................. 1 1.1.2 Production .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Themes and analyses ..................................... 4 1.1.4 Broadcast and reception .................................... 4 1.1.5 Commercial releases ..................................... 4 1.1.6 References and notes ..................................... 5 1.1.7 Bibliography ......................................... 6 1.1.8 External links ......................................... 6 1.2 The Daleks .............................................. 7 1.2.1 Plot .............................................. 7 1.2.2 Production .......................................... 8 1.2.3 Themes and analysis ..................................... 8 1.2.4 Broadcast and reception .................................... 8 1.2.5 Commercial releases ..................................... 9 1.2.6 Film version .......................................... 10 1.2.7 References .......................................... 10 1.2.8 Bibliography ......................................... 10 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 11 1.3 The Edge of Destruction ....................................... 11 1.3.1 Plot .............................................. 11 1.3.2 Production .......................................... 11 1.3.3 Broadcast and reception ...................................