Amur Honeysuckle, Its Fall from Grace James O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

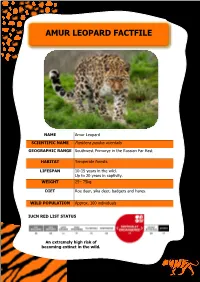

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

Amur Oblast TYNDINSKY 361,900 Sq

AMUR 196 Ⅲ THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST SAKHA Map 5.1 Ust-Nyukzha Amur Oblast TY NDINS KY 361,900 sq. km Lopcha Lapri Ust-Urkima Baikal-Amur Mainline Tynda CHITA !. ZEISKY Kirovsky Kirovsky Zeiskoe Zolotaya Gora Reservoir Takhtamygda Solovyovsk Urkan Urusha !Skovorodino KHABAROVSK Erofei Pavlovich Never SKOVO MAGDAGACHINSKY Tra ns-Siberian Railroad DIRO Taldan Mokhe NSKY Zeya .! Ignashino Ivanovka Dzhalinda Ovsyanka ! Pioner Magdagachi Beketovo Yasny Tolbuzino Yubileiny Tokur Ekimchan Tygda Inzhan Oktyabrskiy Lukachek Zlatoustovsk Koboldo Ushumun Stoiba Ivanovskoe Chernyaevo Sivaki Ogodzha Ust-Tygda Selemdzhinsk Kuznetsovo Byssa Fevralsk KY Kukhterin-Lug NS Mukhino Tu Novorossiika Norsk M DHI Chagoyan Maisky SELE Novovoskresenovka SKY N OV ! Shimanovsk Uglovoe MAZ SHIMA ANOV Novogeorgievka Y Novokievsky Uval SK EN SK Mazanovo Y SVOBODN Chernigovka !. Svobodny Margaritovka e CHINA Kostyukovka inlin SERYSHEVSKY ! Seryshevo Belogorsk ROMNENSKY rMa Bolshaya Sazanka !. Shiroky Log - Amu BELOGORSKY Pridorozhnoe BLAGOVESHCHENSKY Romny Baikal Pozdeevka Berezovka Novotroitskoe IVANOVSKY Ekaterinoslavka Y Cheugda Ivanovka Talakan BRSKY SKY P! O KTYA INSK EI BLAGOVESHCHENSK Tambovka ZavitinskIT BUR ! Bakhirevo ZAV T A M B OVSKY Muravyovka Raichikhinsk ! ! VKONSTANTINO SKY Poyarkovo Progress ARKHARINSKY Konstantinovka Arkhara ! Gribovka M LIKHAI O VSKY ¯ Kundur Innokentevka Leninskoe km A m Trans -Siberianad Railro u 100 r R i v JAO Russian Far East e r By Newell and Zhou / Sources: Ministry of Natural Resources, 2002; ESRI, 2002. Newell, J. 2004. The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development. McKinleyville, CA: Daniel & Daniel. 466 pages CHAPTER 5 Amur Oblast Location Amur Oblast, in the upper and middle Amur River basin, is 8,000 km east of Moscow by rail (or 6,500 km by air). -

Effects of Flood on DOM and Total Dissolved Iron Concentration in Amur River

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-11918, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Effects of Flood on DOM and Total Dissolved Iron Concentration in Amur River Baixing Yan and Jiunian Guan Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Key Laboratory of Wetland Ecology and Environment, China ([email protected]) DOM is an important indicator for freshwater quality and may complex with metals. It is already found that the water quality was abnormal during or after the flood events in various areas, which may be due to the release and resuspending of sediment in the river and leaching of the soil in the river basin area. And flood are also a major pathway for different dissolved matter, such as DOM, transport into the river system from the flood bed, wetlands, etc., when the flood was subsided. River flood has visibly impact on DOM component and concentration. The concentration and species of DOM and dissolved iron during different floods, including watershed extreme flood event, typhoon-induced flood event, snow-thawed flood event were monitored in Amur River and its biggest trib- utary Songhua River. Also, some simulation experiments in lab were implemented. The samples were filtered by 0.45µm filter membrane in situ, then analyze the ionic iron (ferrous ion, Ferric ion) by ET7406 Iron Concentration Tester(Lovibond, Germany with Phenanthroline colorimetric method). The total dissolved iron was determined by GBC 906 AAS(Australia) in lab. DOC was analyzed by TOC VCPH, SHIMADZU(Japan). The results showed that DOC ranged 6.63-9.19 mg/L (averaged at 7.68 mg/L) during extreme Songhua-Amur flood event in 2013.The lower molecular weight of organic matter[U+FF08]<10kDa[U+FF09]was the dominant form of DOM, and the lower molecular weight of complex iron was the dominant form of total dissolved iron. -

Geography – Russia

Year Six RUSSIA Key Facts • Russia (o cial name: Russian Federation) is the world’s largest • Given its size, the climate in Russia varies. The mildest areas country (with an area of 17,075, 200 square kilometres) and are along the Baltic Coast. Winter in Russia is very cold, with has a population of 144, 125, 000. The currency of Russia is the temperatures in the northern regions of Siberia reaching -50 Ruble. degrees Celsius in winter. • The capital city of Russia is Moscow. It has a population 13.2 million people within the city limits and 17 million within the Food and Trade urban areas. It is situated on the Moskva River in western Russia. • Borscht is a famous Russian soup made with beetroot and sour cream. It can be enjoyed hot or cold. Physical and Human Geographical features • St Petersburg is a major trade gateway in Russia, specialising in • Major mountain ranges: Ural, Altai. oil and gas trade, shipbuilding yards and the aerospace industry. • Major rivers: Amur, Irtysh, Lena, Ob, Volga and Yenisey. Russia The fl ag of Russian Federation (Russian: Флаг России) Geographical Skills Key Vocabulary • Children locate the world’s countries on a map, focusing on the • Map: a diagrammatic representation of an area of land showing environmental regions, key physical and human characteristics physical features, cities, roads etc. and major cities of Russia. • Symbol: something that represents or stands for something • Children further their locational knowledge through the else. accurate use of maps, atlases, globes and digital/computer • Key: information needed for a map to make sense. -

Amur (Siberian) Tiger Panthera Tigris Altaica Tiger Survival

Amur (Siberian) Tiger Panthera tigris altaica Tiger Survival - It is estimated that only 350-450 Amur (Siberian) tigers remain in the wild although there are 650 in captivity. Tigers are poached for their bones and organs, which are prized for their use in traditional medicines. A single tiger can be worth over $15,000 – more than most poor people in the region make over years. Recent conservation efforts have increased the number of wild Siberian tigers but continued efforts will be needed to ensure their survival. Can You See Me Now? - Tigers are the most boldly marked cats in the world and although they are easy to see in most zoo settings, their distinctive stripes and coloration provides the camouflage needed for a large predator in the wild. The pattern of stripes on a tigers face is as distinctive as human fingerprints – no two tigers have exactly the same stripe pattern. Classification The Amur tiger is one of 9 subspecies of tiger. Three of the 9 subspecies are extinct, and the rest are listed as endangered or critically endangered by the IUCN. Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Panthera Species: tigris Subspecies: altaica Distribution The tiger’s traditional range is through southeastern Siberia, northeast China, the Russian Far East, and northern regions of North Korea. Habitat Snow-covered deciduous, coniferous and scrub forests in the mountains. Physical Description • Males are 9-12 feet (2.7-3.6 m) long including a two to three foot (60-90 cm) tail; females are up to 9 feet (2.7 m) long. -

Taking Stock of Integrated River Basin Management in China Wang Yi, Li

Taking Stock of Integrated River Basin Management in China Wang Yi, Li Lifeng Wang Xuejun, Yu Xiubo, Wang Yahua SCIENCE PRESS Beijing, China 2007 ISBN 978-7-03-020439-4 Acknowledgements Implementing integrated river basin management (IRBM) requires complex and systematic efforts over the long term. Although experts, scientists and officials, with backgrounds in different disciplines and working at various national or local levels, are in broad agreement concerning IRBM, many constraints on its implementation remain, particularly in China - a country with thousands of years of water management history, now developing at great pace and faced with a severe water crisis. Successful implementation demands good coordination among various stakeholders and their active and innovative participation. The problems confronted in the general advance of IRBM also pose great challenges to this particular project. Certainly, the successes during implementation of the project subsequent to its launch on 11 April 2007, and the finalization of a series of research reports on The Taking Stockof IRBM in China would not have been possible without the combined efforts and fruitful collaboration of all involved. We wish to express our heartfelt gratitude to each and every one of them. We should first thank Professor and President Chen Yiyu of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, who gave his valuable time and shared valuable knowledge when chairing the work meeting which set out guidelines for research objectives, and also during discussions of the main conclusions of the report. It is with his leadership and kind support that this project came to a successful conclusion. We are grateful to Professor Fu Bojie, Dr. -

The Threatened and Near-Threatened Birds of Northern Ussuriland, South-East Russia, and the Role of the Bikin River Basin in Their Conservation KONSTANTIN E

Bird Conservation International (1998) 8:141-171. © BirdLife International 1998 The threatened and near-threatened birds of northern Ussuriland, south-east Russia, and the role of the Bikin River basin in their conservation KONSTANTIN E. MIKHAILOV and YURY B. SHIBNEV Summary Fieldwork on the distribution, habitat preferences and status of birds was conducted in the Bikin River basin, northern Ussuriland, south-east Russia, during May-July 1992,1993, 1995,1996 and 1997. The results of this survey combined with data collected during 1960- 1990, show the area to be of high conservation priority and one of the most important for the conservation of Blakiston's Fish Owl Ketupa blakistoni, Chinese Merganser Mergus squamatus, Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata and Hooded Crane Grus monacha. This paper reports on all of the 13 threatened and near-threatened breeding species of northern Ussuriland, with special emphasis on their occurrence and status in the Bikin area. Three more species, included in the Red Data Book of Russia, are also briefly discussed. Maps show the distribution of the breeding sites of the species discussed. The establishment of a nature reserve in the lower Bikin area is suggested as the only way to conserve the virgin Manchurian-type habitats (wetlands and forests), and all 10 species of special conservation concern. Monitoring of the local populations of Blakiston's Fish Owl, Chinese Merganser and Mandarin Duck in the middle Bikin is required. Introduction No other geographical region of Russia has as rich a biodiversity as Ussuriland which includes the territory of Primorski Administrative Region and the most southern part of Khabarovsk Administrative Region. -

Sino-Russian Transboundary Waters: a Legal Perspective on Cooperation

Sino---Russian-Russian Transboundary Waters: A Legal Perspective on Cooperation Sergei Vinogradov Patricia Wouters STOCKHOLM PAPER December 2013 Sino-Russian Transboundary Waters: A Legal Perspective on Cooperation Sergei Vinogradov Patricia Wouters Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu Sino-Russian Transboundary Waters: A Legal Perspective on Cooperation is a Stockholm Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Stockholm Papers Series is an Occasional Paper series addressing topical and timely issues in international affairs. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publica- tions, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a fo- cal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. The opinions and conclusions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute for Security and Development Pol- icy or its sponsors. © Institute for Security and Development Policy, 2013 ISBN: 978-91-86635-71-8 Cover photo: The Argun River running along the Chinese and Russian border, http://tupian.baike.com/a4_50_25_01200000000481120167252214222_jpg.html Printed in Singapore Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. +46-841056953; Fax. +46-86403370 Email: [email protected] Distributed in North America by: The Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Paul H. -

Phylogeography and Population Genetic Structure of Amur Grayling Thymallus Grubii in the Amur Basin

935 Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. Vol. 25, No. 7 : 935 - 944 July 2012 www.ajas.info http://dx.doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2011.11500 Phylogeography and Population Genetic Structure of Amur Grayling Thymallus grubii in the Amur Basin Bo Ma, Tingting Lui1, Ying Zhang and Jinping Chen1,* Heilongjiang River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Harbin 150070, China ABSTRACT: Amur grayling, Thymallus grubii, is an important economic cold freshwater fish originally found in the Amur basin. Currently, suffering from loss of habitat and shrinking population size, T. grubii is restricted to the mountain river branches of the Amur basin. In order to assess the genetic diversity, population genetic structure and infer the evolutionary history within the species, we analysised the whole mitochondrial DNA control region (CR) of 95 individuals from 10 rivers in China, as well as 12 individuals from Ingoda/Onon and Bureya River throughout its distribution area. A total of 64 variable sites were observed and 45 haplotypes were identified excluding sites with gaps/missing data. Phylogenetic analysis was able to confidently predict two subclade topologies well supported by maximum-parsimony and Bayesian methods. However, basal branching patterns cannot be unambiguously estimated. Haplotypes from the mitochondrial clades displayed local homogeneity, implying a strong population structure within T. grubii. Analysis of molecular variance detected significant differences among the different geographical rivers, suggesting that T. grubii in each river should be managed and conserved separately. (Key Words: Amur Grayling, Population Genetic Structure, Phylogeography, Mitochondrial DNA Control Region) INTRODUCTION zoogeographical faunal complexes in this area (Nicolsigy, 1960). -

Amur Fish: Wealth and Crisis

Amur Fish: Wealth and Crisis ББК 28.693.32 Н 74 Amur Fish: Wealth and Crisis ISBN 5-98137-006-8 Authors: German Novomodny, Petr Sharov, Sergei Zolotukhin Translators: Sibyl Diver, Petr Sharov Editors: Xanthippe Augerot, Dave Martin, Petr Sharov Maps: Petr Sharov Photographs: German Novomodny, Sergei Zolotukhin Cover photographs: Petr Sharov, Igor Uchuev Design: Aleksey Ognev, Vladislav Sereda Reviewed by: Nikolai Romanov, Anatoly Semenchenko Published in 2004 by WWF RFE, Vladivostok, Russia Printed by: Publishing house Apelsin Co. Ltd. Any full or partial reproduction of this publication must include the title and give credit to the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright holder. No photographs from this publication may be reproduced without prior authorization from WWF Russia or authors of the photographs. © WWF, 2004 All rights reserved Distributed for free, no selling allowed Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................................... 5 Amur Fish Diversity and Research History ............................................................................. 6 Species Listed In Red Data Book of Russia ......................................................................... 13 Yellowcheek ................................................................................................................................... 13 Black Carp (Amur) ...................................................................................................................... -

Rivers of Plastic Panama Canal Cruise

Atlantic Ocean Gatun Locks Embera Village ADVANCES Gamboa Gatun Lake Rainforest Resort Cruise Top 10 Polluters Canal Cruise Gaillard Cut Pedro Miguel Locks Circle area shows Total in ocean Mira ores Locks amount of plastic Panama City Yellow Beach Resort Hai Paci c Ocean Indus Daystop Overnight Two Nights Nile Join the smart shoppers & experienced travelers 100,000 All other who have chosen Caravan since 1952 metric tons rivers Plastic from Meghna, Asian rivers Brahmaputra, Panama Plastic from Ganges $ African rivers 8-Days 1295 Pearl Panama Canal Cruise, Beaches, Yangtze and Rainforests Amur Fully guided tour w/ all hotels, all meals, Niger all activities, and a great itinerary. The numbers used in the graphic are based on a model that uses high-end Mekong Your Panama Tour Itinerary estimates of the plastic in each river. Day 1. Welcome to Panama City, Panama. Day 2. Visit the ruins ENVIRONMENT of Panama Viejo. Keel-billed Toucan Day 3. Gatun Lake and Rivers of Plastic VOL. 51, NO. 21; NOVEMBER 2017 7, Panama Canal Cruise. A signifi cant amount of the waste in oceans comes from just 10 rivers Day 4. Cruise more of the Panama Canal. Our seas are choking on plastic. A stag- of all that waste could be pouring in from Day 5. Visit an Embera gering eight million metric tons wind up in just 10 rivers, eight of them in Asia. Pollera Dancer Village in the jungle. oceans every year, and unraveling “Rivers carry trash over long distances Day 6. Free time today exactly how it gets there is critical. -

Institutional Challenges to Transboundary Water Use (Irtysh Basin As a Case Study)

INSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES TO TRANSBOUNDARY WATER USE (IRTYSH BASIN AS A CASE STUDY) Krasnoyarova B.A., Antyufeeva T .V. IWEP SB RAS, ALTAI STATE UNIVERSITY Barnaul July 8- 10, 2019 Republic of Altai Irtysh river basin The river length is 4248 km (in China – 525 km, Kazakhstan – 1835 km, Russia – 2010 km). The basin area is 1643 th km2, the average water consumption below city Tobolsk – 2150 m3/h 2 Major transboundary problems of the Irtysh basin § water resources depletion induced by increased water withdrawal in China and Kazakhstan, evaporative loss from the reservoirs of the cascade hydroelectric systems, e.g. Verkhneirtysh HPSs and other hydraulic structures; § high level of water resources contamination with heavy metals and petroleum products emitted from the enterprises of a mining- metallurgical complex and heat power engineering systems operating in the upper reaches of the Irtysh; § radioactive contamination of the territory caused by the Semipalatinsk (Russia) and Lop Nur (China) nuclear test sites, "Mayak" industrial association , etc.; § critical state of hydraulic structures; § lack of legal mechanisms for regulating water use in transboundary countries. 3 Water resources depletion Increased water withdrawal by China; § R. Kara-Irtysh (Black Irtysh) runoff formation in China (approximately 9.0 km3/year); § current water withdrawal makes up 1.0 - 1.5 km3/year; § In China: § In the future water withdrawal will increase up to 4.0 - 5.0 km3/year due to the oil –field development nearby Karamay town and water intake for other purposes. In Kazakhstan: § The construction of Bulaksk HPP (as a distribution reservoir of Shulbinskaya HPP) with a capacity of 68 MW; the restoration of Ulbinsk HPP ( 27 MW) by "LenGES"; the repair and installation of HPPs in Ust’-Kamenogorsk and Semey; the construction of 2 mini and 13 small HPPs, including Turgusun HPP.