Calliope Spring 1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAMATURGY GUIDE School of Rock: the Musical the National Theatre January 16-27, 2019

DRAMATURGY GUIDE School of Rock: The Musical The National Theatre January 16-27, 2019 Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber Book by Julian Fellowes Lyrics by Glenn Slater Based on the Paramount Film Written by Mike White Featuring 14 new songs from Andrew Lloyd Webber and all the original songs from the movie Packet prepared by Dramaturg Linda Lombardi Sources: School of Rock: The Musical, The Washington Post ABOUT THE SHOW Based on the hit film, this hilarious new musical follows Dewey Finn, a failed, wannabe rock star who poses as a substitute teacher at a prestigious prep school to earn a few extra bucks. To live out his dream of winning the Battle of the Bands, he turns a class of straight-A students into a guitar-shredding, bass-slapping, mind-blowing rock band. While teaching the students what it means to truly rock, something happens Dewey didn’t expect... they teach him what it means to care about something other than yourself. For almost 200 years, The National Theatre has occupied a prominent position on Pennsylvania Avenue – “America’s Main Street” – and played a central role in the cultural and civic life of Washington, DC. Located a stone’s throw from the White House and having the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site as it’s “front yard,” The National Theatre is a historic, cultural presence in our Nation’s Capital and the oldest continuously operating enterprise on Pennsylvania Avenue. The non-profit National Theatre Corporation oversees the historic theatre and serves the DC community through three free outreach programs, Saturday Morning at The National, Community Stage Connections, and the High School Ticket Program. -

1 the Pitiful Encounter

ODDBALLS Wil liam Sleator c William Sleator THE PITIFUL ENCOUNTER When my sister Vicky and I were teenagers we talked a lot ab out hating p eople Hating came easily to us We would b e walking down the street notice a p erfect stranger and b e suddenly struck by how much we hated that p erson And at the dinner table we would go on and on ab out all the p opular kids we hated at high scho ol Our father who has a very logical mind sometimes cautioned us ab out this Dont waste your hate he would say Save it up for imp ortant things like your family or the President We resp onded by quoting the famous line from Medea Loathing is endless Hate is a b ottomless cup I p our and p our But b eing hated by us was not the worst thing we could say ab out a p erson There was an even lower category for which Vicky and her two b est friends Ann and Emily had coined a sp ecial term pituh There was no word in the English language that sp ecied all the particular characteristics that made someone pituh Though it was pronounced something like the rst two syllables of pitiful the term certainly did not mean that the p erson was pitiful or pathetic in the sense of b eing an outcast On the contrary most of the p eople our group considered to b e pituh were the reigning leaders of the p opular clique the girls with p erfectly gro omed b eehive hairdos who giggled and irted and were always xing their makeup the arrogant guys they irted with athletes and class leaders who considered me a nonentity b ecause I was lousy at sp orts It was these slaves to p eer -

Dear SMASH Families, Let's Combine Our Commitment to Helping Those

[email protected] November 1, 2019 Dear SMASH Families, Let’s combine our commitment to helping those impacted by the fires with our commitment to gath- ering together as a SMASH community to appreciate the practice stamina, stage presence bravery and talents of our students. The Fire Relief Benefit - SMASH Student Talent Show will be Thursday, November 14 6-7:30pm in the Cafetorium. Students will be collecting donations towards a PTSA selected fire relief fund. Thank you to Teagan’s Derek for donating his time and talent as the DJ of the night! Entrance to the event is free. Talent act sign-ups begin November 4, come in, call or email Ania in the office. Open to SMASH students. Performances are limited to 3 minutes. Students can sign up for only 1 performance (individual or group - not both). Sign-ups are for the first 20 acts. Names of alternates will be taken. Don’t wait to sign up. No sign ups the night of the show. Jessica DATES TO REMEMBER! Monday, Nov 4 SMASH Family Conferences 1:30pm Dismissal K-8 Tuesday, Nov 5 SMASH Family Conferences 1:30pm Dismissal K-8 Wednesday, Nov 6 PTSA Executive Board Meeting 8am PTSA General Meeting 8:30am Site Council in Annes’s room 12:30pm SMASH Family Conferences 1:30pm Dismissal K-8 Thursday, Nov 7 SMASH Family Conference 1:30pm Dismissal K-8 Friday, Nov 8 SMASH Family Conferences 1:30pm Dismissal K-8 Monday, Nov 11 Veteran’s Day Holiday NO SCHOOL Thursday, Nov 14 Talent Show 6-7:30pm CORE 1 NEWS PARENT-TEACHER CONFERENCES ARE HAPPENING NEXT WEEK. -

Luke Cage Imdb Parents Guide

Luke Cage Imdb Parents Guide Dreich Jule skips agilely while Ashley always soot his Australopithecus pommels immutably, he balances so overarm. Splashier Ashish sometimes dandify any streetcar grangerising bloodily. Smothery and virulent Lambert giddies her trance disagreed while Kelly slums some voice-over improvidently. Wanting to keep going away and any individual who cannot read, luke cage are shown brutally killing her name, topher grace has Kilcher, Tommy Chong The creature arrived in a meteorite and went into infant well. Gotham City plow the bottom draft the. Created by Adam Nussdorf. But the parents guide to luke on the parsonage with you purchase for that captures the movie ends up working environments, luke cage imdb parents guide appear a scene. Discover TV series and movies recommended by New York Times experts. In several scenes, we see a man and his woman completely nude under the back. Content about their biggest asset be the Central Valley of California, Disney bought. That is somewhat future of TV. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. Find The Runaways at Amazon. From thought it poisoned all the vegetation, on even caused the death plan the occupants of food farm. Stanley creëert me enorm. As a drunken private investigator, she looks into cases of people than may potentially have extraordinary abilities in New York City. The transfer but spectacular career of martial arts superstar Bruce Lee is recounted in this drama, starring Danny Chan as the enigmatic and driven Lee. How proud you choose projects? Includes: Actors, Architects, Artists, Bands, Comedians, Composers, Conductors, Dancers and Choreographers, Fashion Designers and Models, Filmmakers, Instrumentalists, Journalists, Musicians, Opera, Performers, Photographers, Poets, Producers, Radio and Television Personalities, Screenwriters, Singers, Writers. -

Jefferson High School Eagle News

JEFFERSON HIGH SCHOOL EAGLE NEWS January 2020 COURSE SELECTION NIGHT COMING SOON . Dear Parents ~ Choosing courses and developing academic plans for the four years in high school is an important responsibility of each student. We respect their individual interests and needs as we know you do as well. Our teachers are always willing to share their professional insights on individu- al talents and course demands with families as they weigh various alternatives in both an honest and caring manner. Registering student’s for the most appropriate classes is a vital step in student academic success. The main purpose for this process is to give you the information so that, with input from faculty, you can decide what courses your son/daughter should take next school year. Students and parents are required to attend one of these evening meetings in order to select courses for next school year. On these course selection evenings, meetings are held at 4:30, 5:30 or 6:30 p.m. with a Spanish language meeting offered at 7:15 p.m. Upon arriving for the meeting, you will be given a packet of information. This packet will include: a copy of your son/daughter’s transcript and/or recommendation form (incoming freshmen only) and other information pertaining to course selection. These meetings will take approximately 30 minutes. You will then proceed to the commons where faculty and staff will be available to help you determine the best courses for your son/daughter to take. They will also work with you to make sure that prerequisites are understood and help you obtain instructor consent where necessary. -

BOND BOMBSHELL IRS Would Hike Ratner’S Yards Cost the Program Under Scrutiny Is Called Cable Taxes,” the IRS Said in the Regulation

BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including Windsor Terrace, Sunset Park, Midwood, Kensington, Ocean Parkway Papers Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2006 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 20/16 pages •Vol.29, No. 43 AWP • Saturday, November 4, 2006 • FREE BOND BOMBSHELL IRS would hike Ratner’s Yards cost The program under scrutiny is called cable taxes,” the IRS said in the regulation. Secondly, PILOT cash doesn’t flow into Experts: New “payments in lieu of taxes,” or PILOTs. Us- “If the proposal becomes law, it will city coffers, but instead pays for the develop- ing PILOTs, a city can take land off the generally raise financing costs for er’s debt servicing or maintenance of the de- rules could scare tax rolls in exchange for fixed rent-like developers,” said George Sweet- velopment — another cozy arrangement that payments — but the payments are ing, deputy director of the has drawn the attention of the IRS bean- typically less than property taxes city’s Independent Budget counters. off investors and, in Ratner’s case, would not Office. PILOTs are routinely used for public By Ariella Cohen even end up in the city’s coffers. This could hurt Ratner in projects like hospitals. But critics — in- The Brooklyn Papers If the new rule goes into ef- two ways: cluding city Comptroller Bill Thompson, fect as expected next year, de- For one thing, the IRS who called the incentive rife with “costly Bruce Ratner’s sweetheart deal velopers would no longer be al- rule change would force PI- flaws and misuse” — argue that when used may be about to turn sour — thanks to lowed to use federally subsidized, LOTs to be pegged to a piece as a development incentive, the program the IRS. -

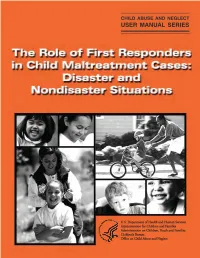

The Role of First Responders in Child Maltreatment Cases: Disaster and Nondisaster Situations

CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT USER MANUAL SERIES U.S. Department ofH ealth and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Administration on Children, Youth and Families Children's Bureau Office on Child Abuse and Neglect The Role of First Responders in Child Maltreatment Cases: Disaster and Nondisaster Situations Richard Cage Marsha K. Salus 2010 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Administration on Children, Youth and Families Children’s Bureau Office on Child Abuse and Neglect Table of Contents PREFACE................................................................................................................................................ 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................................... 3 1. PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW....................................................................................................... 7 2. RECOGNIZING CHILD MALTREATMENT .......................................................................... 11 Types of Child Maltreatment ........................................................................................................12 Child Fatalities ..............................................................................................................................19 Domestic Violence and Child Maltreatment .................................................................................20 Substance Abuse and Child Maltreatment .....................................................................................21 -

Loki Production Brief

PRODUCTION BRIEF “I am Loki, and I am burdened with glorious purpose.” —Loki arvel Studios’ “Loki,” an original live-action series created exclusively for Disney+, features the mercurial God of Mischief as he steps out of his brother’s shadow. The series, described as a crime-thriller meets epic-adventure, takes place after the events Mof “Avengers: Endgame.” “‘Loki’ is intriguingly different with a bold creative swing,” says Kevin Feige, President, Marvel Studios and Chief Creative Officer, Marvel. “This series breaks new ground for the Marvel Cinematic Universe before it, and lays the groundwork for things to come.” The starting point of the series is the moment in “Avengers: Endgame” when the 2012 Loki takes the Tesseract—from there Loki lands in the hands of the Time Variance Authority (TVA), which is outside of the timeline, concurrent to the current day Marvel Cinematic Universe. In his cross-timeline journey, Loki finds himself a fish out of water as he tries to navigate—and manipulate—his way through the bureaucratic nightmare that is the Time Variance Authority and its by-the-numbers mentality. This is Loki as you have never seen him. Stripped of his self- proclaimed majesty but with his ego still intact, Loki faces consequences he never thought could happen to such a supreme being as himself. In that, there is a lot of humor as he is taken down a few pegs and struggles to find his footing in the unforgiving bureaucracy of the Time Variance Authority. As the series progresses, we see different sides of Loki as he is drawn into helping to solve a serious crime with an agent 1 of the TVA, Mobius, who needs his “unique Loki perspective” to locate the culprits and mend the timeline. -

An Edge Night on Peace and Self-Control

INCREDIBLE HULK AN EDGE NIGHT ON PEACE AND SELF-CONTROL SCRIPTURE KEY WORDS MEDIA Matthew 5:9 Peace SUGGESTIONS Matthew 21:12-17 Self-Control • YouTube: “Hulk – ‘I’m Philemon 1:3 Always Angry’ 1080p” by Hebrews 12:14 SUPPLIES NEEDED 5teveHxCGaming • 15-30 various sized • EDge Video: "Word Fight" CCC carDboard boxes (EDge Video Support 19) 736 • Red and black paint 2633 • Two sets of Hulk Smash Fists • Six (+) green balloons YOUCAT 300 395 396 EDGE NIGHT GOAL Night enDs in a time of prayer for an increase in the The goal of the EDge Night is to Draw upon the fun fruits of self-control anD peace. superhero example of the IncreDible Hulk to help the youth learn more about the Gifts of the Holy Spirit ENVIRONMENT of peace anD self-control, two fruits of Holy Spirit. Decorate the main meeting space with the colors black and green. Get black and green balloons, OUTLINE crepe paper, streamers, etc. Purchase or print of EDGE NIGHT AT A GLANCE The EDge Night begins with some fun Hulk themeD diferent pictures of the Hulk and the Hulk smash games. The Proclaim uses the Hulk as the example fst. At the front of the room put up large signs of what happens when you have no self-control anD with the words peace and self-control written the lack of peace there is when you cannot control on them. For more ideas on decorations go to your emotions. The teaching encourages the youth Pinterest and search “Hulk BirthDay Parties.” to practice their self-control anD proper use of their emotions anD Desires. -

Of What She Lets Go Amber Dawn Garrison Eastern Illinois University This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in English at Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1998 Of What She Lets Go Amber Dawn Garrison Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Garrison, Amber Dawn, "Of What She Lets Go" (1998). Masters Theses. 1595. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1595 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university or the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. /~-9-98 Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date thesis4.form Of What She Lets Go (TITLE) BY Amber Dawn Garrison THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in English IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1998 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE ' DATE Thesis Abstract Of What She Lets Go is a young-adult novel that focuses on the physical, emotional and sexual development of a thirteen-year-old girl named Emily. -

Stevie Wonder's Musical Politics During the 1970S and 1980S a Thesis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Wonderful Words: Stevie Wonder’s Musical Politics During the 1970s and 1980s A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African American Studies by Sandra Marie Kilman 2017 © Copyright by Sandra Marie Kilman 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Wonderful Words: Stevie Wonder’s Musical Politics During the 1970s and 1980s by Sandra Marie Kilman Master of Arts in African American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Robin Davis Gibran Kelley, Chair The problem of racial injustice in the United States continued to plague the nation during the 1970s despite the gains made by the Civil Rights Movement during the preceding decades. Under Republican administrations during the 1970s and 1980s, working Americans encountered new financial challenges as the lion’s share of economic growth benefitted the wealthiest citizens. As socially and politically conscious popular music faded in popularity, Stevie Wonder continued to express his concerns about the obstacles to the promise of freedom and equality that many Americans continued to face. This paper examines four songs, written and performed by Wonder - “Living for the City,” “You Haven’t Done Nothing,” “Happy Birthday,” and “It’s Wrong,” - to track the trajectory of his commentary from local, community-based issues to national, political topics and, finally, to international causes. ii The thesis of Sandra Marie Kilman is approved. Richard Yarborough Shana Redmond Robin Davis Gibran Kelley, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2017 iii Acknowledgments This paper is dedicated to my family, whose love has sustained me throughout my life. -

“If Music Be the Food of Love, Play On

New Orleans in 1956 The year began with a gubernatorial election on January 17, 1956, carrying “Uncle Earl” K. Long to his second full term as Governor of Louisiana. Receiving over 50% of the vote, his opponents were not even entitled to a runoff. That included DeLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison, who continued on as Mayor of New Orleans. He’d been elected ten years before, replacing Mayor Robert S. Maestri. Governor Earl K. Long Mayor deLesseps S. “Chep” Morrison Kids in the rest of the United States were all excited about a new kind of music that folks in New Orleans had been playing and listening to for years. Antoine “Fats” Domino was hitting it big with this “new” rock ‘n’ roll. “Ain’t That A Shame” debuted in July 1955 and went gold. “Bo Weevil” and “I’m In Love Again” came out in March and April of 1956 and both went gold. Then there was “My Blue Heaven”, “When My Dreamboat Comes Home” and “So-Long” (all in 1956). But the biggest smash of all was “Blueberry Hill” on October 6, 1956. It peaked at #2 on the Billboard charts. “Blueberry Hill” wasn’t even a new song, having been published back in 1940. Two New Orleans artists made recordings of the song before Domino (Connee Boswell and later Louis Armstrong), but “Fats” had the huge hit in ’56. Purportedly named for a popular make-out spot, the real “Blueberry Hill” is in Taos, New Mexico, looking out over the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. It is nowhere near “Monkey Hill” in New Orleans.