China's Soft Power in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soft Power Amidst Great Power Competition

Soft Power Amidst Great Power Competition May 2018 Irene S. Wu, Ph.D. What is soft power? Soft power is a country’s ability to persuade other countries to follow it. Soft power is about a country’s culture, values, and outlook attracting and influencing other countries. It contrasts with military or economic power. Harvard University’s Joseph Nye coined the term in the 1990’s in part to explain the end of the Cold War. Maybe burgers and rock and roll, not just missiles and money, contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.1 Why does soft power matter? Research shows that for big issues like war and peace, public opinion in foreign countries has an effect on whether they join the United States in military action. Foreign public opinion matters less on smaller issues like voting in the United Nations.2 Non-U.S.-citizens can love American culture but disagree with U.S. government policies. However, there is a difference between criticisms from countries with close ties compared to those with few ties. 3 The meaning of feedback from friends is different from that of strangers. Why is it useful to measure soft power? Until now, there were two approaches to soft power–relying entirely on stories or ranking countries on a list. Relying entirely on stories is useful and essential, but makes it hard to compare countries with each other or across time. Ranking countries on a single list makes it seem there is only one kind of soft power and that a country’s soft power relationship with every Soft Power Amidst Great Power Competition other country is the same.4 A framework which takes advantage of the available quantitative data that also integrates well with the stories, narratives, and other qualitative analysis is necessary to understand fully soft power. -

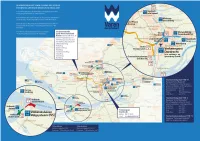

Rapport Toetsing Realisatiecijfers Vervoer Gevaarlijke Stoffen Over Het Water Aan De Risicoplafonds Basisnet

RWS INFORMATIE Rapport toetsing realisatiecijfers vervoer gevaarlijke stoffen over het water aan de risicoplafonds Basisnet Jaar: 2018 Datum 20 mei 2019 Status Definitief RWS INFORMATIE Monitoringsrapportage water 2018 20 mei 2019 Colofon Uitgegeven door Rijkswaterstaat Informatie Mevr. M. Bakker, Dhr. G. Lems Telefoon 06-54674791, 06-21581392 Fax Uitgevoerd door Opmaak Datum 20 mei 2019 Status Definitief Versienummer 1 RWS INFORMATIE Monitoringsrapportage water 2018 20 mei 2019 Inhoud 1 Inleiding—6 1.1 Algemeen 1.2 Registratie en risicoberekening binnenvaart 1.3 Registratie en risicoberekening zeevaart 1.4 Referentiehoeveelheden 2 Toetsing aan de risicoplafonds—9 2.1 Overzicht toetsresultaten 2.2 Toetsresultaten per traject 2.3 Kwalitatieve risicoanalyse Basisnet-zeevaartroutes 3 Realisatie—13 Bijlage 1 ligging basisnetroutes per corridor Bijlage 2a realisatiecijfers binnenvaart op zeevaartroutes Bijlage 2b realisatiecijfers zeevaart op zeevaartroutes Bijlage 3 realisatiecijfers binnenvaart op binnenvaartroutes Bijlage 4 invoer en rekenresultaten RBMII berekeningen Bijlage 5 aandeel LNG in GF3 binnenvaart Bijlage 6 aandeel LNG in GF3 zeevaart RWS INFORMATIE | Monitoringsrapportage water 2018 | 20 mei 2019 1 Inleiding 1.1 Algemeen Op basis van artikel 15 van de Wet vervoer gevaarlijke stoffen en de artikelen 9 tot en met 12 van de Regeling Basisnet is de Minister verplicht om te onderzoeken in hoeverre één of meer van de in de Regeling Basisnet opgenomen risicoplafonds worden overschreden. De Regeling Basisnet is per 1 april 2015 in werking getreden. Deze rapportage bevat de resultaten van de toetsing van de realisatiecijfers van het vervoer gevaarlijke stoffen over het water aan de risicoplafonds Basisnet over het jaar 2018. De verscheidenheid aan vervoerde stoffen over de transportroutes is zo groot, dat een risicoanalyse per stof zeer arbeidsintensief zal zijn. -

SPACE RESEARCH in POLAND Report to COMMITTEE

SPACE RESEARCH IN POLAND Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) 2020 Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) ISBN 978-83-89439-04-8 First edition © Copyright by Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Warsaw, 2020 Editor: Iwona Stanisławska, Aneta Popowska Report to COSPAR 2020 1 SATELLITE GEODESY Space Research in Poland 3 1. SATELLITE GEODESY Compiled by Mariusz Figurski, Grzegorz Nykiel, Paweł Wielgosz, and Anna Krypiak-Gregorczyk Introduction This part of the Polish National Report concerns research on Satellite Geodesy performed in Poland from 2018 to 2020. The activity of the Polish institutions in the field of satellite geodesy and navigation are focused on the several main fields: • global and regional GPS and SLR measurements in the frame of International GNSS Service (IGS), International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS), International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), European Reference Frame Permanent Network (EPN), • Polish geodetic permanent network – ASG-EUPOS, • modeling of ionosphere and troposphere, • practical utilization of satellite methods in local geodetic applications, • geodynamic study, • metrological control of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) equipment, • use of gravimetric satellite missions, • application of GNSS in overland, maritime and air navigation, • multi-GNSS application in geodetic studies. Report -

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director.—Michael Mastrian Deputy Director.—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator.—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinator.—Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director.—Tina Tate Deputy Director.—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistant for Administrative Operations.—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations.—Andy Elias Assistants: Gerald Rupert, Kimberly Oates EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

China's Soft Power in East Asia

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #42 | january 2013 china’s soft power in east asia A Quest for Status and Influence? By Chin-Hao Huang cover 2 The NBR Special Report provides access to current research on special topics conducted by the world’s leading experts in Asian affairs. The views expressed in these reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of other NBR research associates or institutions that support NBR. The National Bureau of Asian Research is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research institution dedicated to informing and strengthening policy. NBR conducts advanced independent research on strategic, political, economic, globalization, health, and energy issues affecting U.S. relations with Asia. Drawing upon an extensive network of the world’s leading specialists and leveraging the latest technology, NBR bridges the academic, business, and policy arenas. The institution disseminates its research through briefings, publications, conferences, Congressional testimony, and email forums, and by collaborating with leading institutions worldwide. NBR also provides exceptional internship opportunities to graduate and undergraduate students for the purpose of attracting and training the next generation of Asia specialists. NBR was started in 1989 with a major grant from the Henry M. Jackson Foundation. Funding for NBR’s research and publications comes from foundations, corporations, individuals, the U.S. government, and from NBR itself. NBR does not conduct proprietary or classified research. The organization undertakes contract work for government and private-sector organizations only when NBR can maintain the right to publish findings from such work. To download issues of the NBR Special Report, please visit the NBR website http://www.nbr.org. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 31 March 2008

United Nations A/CN.4/596 General Assembly Distr.: General 31 March 2008 Original: English International Law Commission Sixtieth session Geneva, 5 May-6 June and 7 July-8 August 2008 Immunity of State officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction Memorandum by the Secretariat 08-29075 (E) 141108 *0829075* A/CN.4/596 Summary The present study, prepared by the Secretariat at the request of the International Law Commission, is intended to provide a background to the Commission’s consideration of the topic “Immunity of State officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction”. The study examines the main legal issues that arise in connection with this topic, both from classical and contemporary perspectives, also taking into account developments in the field of international criminal law that might have produced an impact on the immunities of State officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction. Three limitations to the scope of the study need to be emphasized. First, the study only deals with immunities of those individuals that are State officials, as opposed to other individuals — for example, agents of international organizations — who may also enjoy immunities under international law. Furthermore, the study does not cover certain categories of State officials such as diplomats and consular agents, since the rules governing their privileges and immunities have already been a subject of codification. However, reference is made, as appropriate, to such rules where they might provide useful elements in addressing certain issues on which practice regarding the individuals covered by the present study appears to be scant. Secondly, the study is limited to immunities from criminal jurisdiction, as opposed to other types of jurisdiction such as civil. -

Indigenous and Social Movement Political Parties in Ecuador and Bolivia, 1978-2000

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Democratizing Formal Politics: Indigenous and Social Movement Political Parties in Ecuador and Bolivia, 1978-2000 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Jennifer Noelle Collins Committee in charge: Professor Paul Drake, Chair Professor Ann Craig Professor Arend Lijphart Professor Carlos Waisman Professor Leon Zamosc 2006 Copyright Jennifer Noelle Collins, 2006 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Jennifer Noelle Collins is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION For my parents, John and Sheila Collins, who in innumerable ways made possible this journey. For my husband, Juan Giménez, who met and accompanied me along the way. And for my daughter, Fiona Maité Giménez-Collins, the beautiful gift bequeathed to us by the adventure that has been this dissertation. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE.……………………..…………………………………...…...…iii DEDICATION .............................................................................................................iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................v -

Blokkanalen Zuid-Holland

TOELICHTING MARIFOONKAART ALGEMEEN NAUTISCH INFORMATIEKANAAL VHF 71 CANAL D’INFORMATIONS GENERALES SUR LA ALGEMEINER INFORMATIONSKANAL VHF 71 GENERAL nautical INFORMATION CHANNEL VHF 71 Roepnaam: “Verkeerspost Dordrecht”. Uitluisteren is niet NAVIGATION VHF 71 Rufname: “Verkeerspost Dordrecht”, das Abhören dieses Call sign: “Verkeerspost Dordrecht”. It is not compulsory verplicht. Op dit kanaal kan men nautische informatie opvragen of Nom du code: “Poste de traffic de Dordrecht”. Il n’est pas nécessaire de Kanals ist nicht obligatorisch. Auf diesem Kanal können Schiffer to maintain a listening on this channel. On this channel nautical bijzonderheden melden. Op het nautisch informatiekanaal kunnen rester à l’écoute. Ce canal permet d’obtenir des informations particulières nautische Informationen einholen oder der Regionalen Verkehrszentrale information can be requested or reported. If necessary, urgent uurberichten uitgezonden worden van dringende nautische aard. sur la navigation ou de faire passer des messages importants au Centre Dordrecht nautische Details melden. Auf diesem nautischen nautical bulletins (every hour ) are broadcast on this channel within Daarnaast is dit kanaal bestemd voor het inwinnen van Informatie Volg régional du trafic fluvial de Dordrecht. Des messages urgents concernant Informationskanal können stündlich Berichte dringender nautischer the operational area. This channel is also intended to enable to obtain Systeem (IVS) gegevens. Dit kanaal is tevens bestemd voor het aan- en la navigation à l’intérieur de la zone relevant du Centre sont diffusés Art übermittelt werden. Ausserdem wird dieser Kanal verwendet für die reporting- and tracking system data. this channel is intended to sign in afmelden van het gebruik van de overnachtingshavens en ankerplaatsen. toutes les heures. Le canal peut également être utilisé pour obtenir les erforderlichen Daten des Melde- und Beobachtungssytems, IVS. -

Latvia by Juris Dreifelds

Latvia by Juris Dreifelds Capital: Riga Population: 2.1 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$19,090 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’sWorld Development Indicators 2013. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Electoral Process 1.75 1.75 1.75 2.00 2.00 2.00 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 Civil Society 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Independent Media 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Governance* 2.25 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a 2.25 2.00 2.00 2.00 2.50 2.50 2.25 2.25 2.25 Local Democratic Governance n/a 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 Judicial Framework and Independence 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Corruption 3.50 3.50 3.25 3.00 3.00 3.25 3.25 3.50 3.25 3.00 Democracy Score 2.17 2.14 2.07 2.07 2.07 2.18 2.18 2.14 2.11 2.07 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the