China's Soft Power in East Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soft Power Amidst Great Power Competition

Soft Power Amidst Great Power Competition May 2018 Irene S. Wu, Ph.D. What is soft power? Soft power is a country’s ability to persuade other countries to follow it. Soft power is about a country’s culture, values, and outlook attracting and influencing other countries. It contrasts with military or economic power. Harvard University’s Joseph Nye coined the term in the 1990’s in part to explain the end of the Cold War. Maybe burgers and rock and roll, not just missiles and money, contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.1 Why does soft power matter? Research shows that for big issues like war and peace, public opinion in foreign countries has an effect on whether they join the United States in military action. Foreign public opinion matters less on smaller issues like voting in the United Nations.2 Non-U.S.-citizens can love American culture but disagree with U.S. government policies. However, there is a difference between criticisms from countries with close ties compared to those with few ties. 3 The meaning of feedback from friends is different from that of strangers. Why is it useful to measure soft power? Until now, there were two approaches to soft power–relying entirely on stories or ranking countries on a list. Relying entirely on stories is useful and essential, but makes it hard to compare countries with each other or across time. Ranking countries on a single list makes it seem there is only one kind of soft power and that a country’s soft power relationship with every Soft Power Amidst Great Power Competition other country is the same.4 A framework which takes advantage of the available quantitative data that also integrates well with the stories, narratives, and other qualitative analysis is necessary to understand fully soft power. -

New Media in New China

NEW MEDIA IN NEW CHINA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEMOCRATIZING EFFECT OF THE INTERNET __________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, East Bay __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Communication __________________ By Chaoya Sun June 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Chaoya Sun ii NEW MEOlA IN NEW CHINA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEMOCRATIlING EFFECT OF THE INTERNET By Chaoya Sun III Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 PART 1 NEW MEDIA PROMOTE DEMOCRACY ................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 THE COMMUNICATION THEORY OF HAROLD INNIS ........................................ 10 NEW MEDIA PUSH ON DEMOCRACY .................................................................... 13 Offering users the right to choose information freely ............................................... 13 Making free-thinking and free-speech available ....................................................... 14 Providing users more participatory rights ................................................................. 15 THE FUTURE OF DEMOCRACY IN THE CONTEXT OF NEW MEDIA ................ 16 PART 2 2008 IN RETROSPECT: FRAGILE CHINESE MEDIA UNDER THE SHADOW OF CHINA’S POLITICS ........................................................................... -

The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship: How the Communist Party’S Media Restrictions Affect News Outlets Around the World

The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship: How the Communist Party’s Media Restrictions Affect News Outlets Around the World A Report to the Center for International Media Assistance By Sarah Cook October 22, 2013 The Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA), at the National Endowment for Democracy, works to strengthen the support, raise the visibility, and improve the effectiveness of independent media development throughout the world. The Center provides information, builds networks, conducts research, and highlights the indispensable role independent media play in the creation and development of sustainable democracies. An important aspect of CIMA’s work is to research ways to attract additional U.S. private sector interest in and support for international media development. CIMA convenes working groups, discussions, and panels on a variety of topics in the field of media development and assistance. The center also issues reports and recommendations based on working group discussions and other investigations. These reports aim to provide policymakers, as well as donors and practitioners, with ideas for bolstering the effectiveness of media assistance. Don Podesta Interim Senior Director Center for International Media Assistance National Endowment for Democracy 1025 F Street, N.W., 8th Floor Washington, DC 20004 Phone: (202) 378-9700 Fax: (202) 378-9407 Email: [email protected] URL: http://cima.ned.org Design and Layout by Valerie Popper About the Author Sarah Cook Sarah Cook is a senior research analyst for East Asia at Freedom House. She manages the editorial team producing the China Media Bulletin, a biweekly news digest of media freedom developments related to the People’s Republic of China. -

A Global Ranking of Soft Power 2018 2 the SOFT POWER 30 SECTION HEADER 3

A Global Ranking of Soft Power 2018 2 THE SOFT POWER 30 SECTION HEADER 3 Designed by Portland's in-house Content & Brand team. 60 116 The Indo-Pacific in focus: Soft power platforms: old and new The Asia Soft Power 10 The transformational (soft) power of museums: India rising: soft power and the world’s at home and abroad largest democracy Tristram Hunt, Victoria and Albert Museum Dhruva Jaishankar, Brookings India The quest for Reputational Security: interpreting The ASEAN we don’t know the soft power agenda of Kazakhstan and other Ong Keng Yong, RSIS newer states CONTENTS Nicholas J. Cull, USC Center on Public Diplomacy China goes global: why China’s global cultural strategy needs flexibility Reimagining the exchange experience: the local Zhang Yiwu, Peking University impact of cultural exchanges Jay Wang and Erik Nisbet, USC Center on Japan: Asia’s soft power super power? Public Diplomacy Jonathan Soble, Asia Pacific Initiative #UnknownJapan: inspiring travel with Instagram 7 16 Australia in Asia: the odd man out? Max Kellett, Portland Richard McGregor, Lowy Institute Contributors Introduction Table talk: bringing a Swiss Touch to the American public Disorderly conduct The two Koreas and soft power Aidan Foster-Carter, Leeds University Olivia Harvey, Portland Order up? The Asia Soft Power 10 Soft power and the world’s game: the Premier The 2018 Soft Power 30 League in Asia 12 Jonathan McClory, Portland 92 The Soft Power 30 30 Public diplomacy and the decline of liberal New coalitions of the willing & democracy Methodology of the index -

Soft Power and Public Diplomacy: the Case of the European Union in Brazil by María Luisa Azpíroz

Soft Power and Public Diplomacy: The Case of the European Union in Brazil By María Luisa Azpíroz CPD Perspectives on Public Diplomacy Paper 2, 2015 Soft Power and Public Diplomacy: The Case of the European Union in Brazil María Luisa Azpíroz March 2015 Figueroa Press Los Angeles SOFT POWER AND PUBLIC DIPLOMACY: THE CASE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION IN BRAZIL by María Luisa Azpíroz Published by FIGUEROA PRESS 840 Childs Way, 3rd Floor Los Angeles, CA 90089 Phone: (213) 743-4800 Fax: (213) 743-4804 www.figueroapress.com Figueroa Press is a division of the USC Bookstores Cover, text, and layout design by Produced by Crestec, Los Angeles, Inc. Printed in the United States of America Notice of Rights Copyright © 2015. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without prior written permission from the author, care of Figueroa Press. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the author nor Figueroa nor the USC University Bookstore shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by any text contained in this book. Figueroa Press and the USC Bookstores are trademarks of the University of Southern California. -

Multilateral Cooperation, the G20 and the EU: Soft Power for Greater Policy Coherence? Bernard Hoekman* and Rorden Wilkinson†

Multilateral Cooperation, the G20 and the EU: Soft Power for Greater Policy Coherence? Bernard Hoekman* and Rorden Wilkinson† Revised: February 15, 2020 Abstract: Since 2008, G20 leaders have repeatedly committed themselves to conclude WTO negotiations expeditiously and refrain from resorting to protectionism. They have not, however, lived up to these commitments. Trade growth has been anemic for much of the intervening period, with deadlock in the WTO and reversion to aggressive unilateralism by the United States undermining global trade governance. Current trade tensions primarily involve the major trading powers. Resolving these tensions requires agreement between the main actors and greater focus on addressing the concerns of all WTO members regarding the operation of the organization. The major actors are all members of the G20. The G20 constitutes an important forum for the EU to provide leadership and to use its soft power to address geo-economic conflicts and bolster global trade governance. We review the prospects for resolving current trade tensions and revitalizing the multilateral system through a discussion of the measures that could constitute EU trade leadership in the G20. Keywords: EU, G20, trade governance, WTO, economic development JEL Codes: E61; F02; F42; F68 Acknowledgement. We are grateful to San Bilal, Peter Holmes, Massimo de Luca, Jacques Pelkmans and participants in a January 20-21, 2020 RESPECT project workshop at the Centre for European Policy Studies in Brussels for helpful comments and suggestions. The project leading to this article received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 770680 (RESPECT). * Professor and Director, Global Economics at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute in Florence, Italy. -

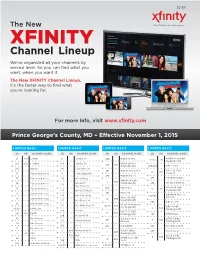

XFINITY Channel Lineup We’Ve Organized All Your Channels by Service Level

2C-307 The New XFINITY Channel Lineup We’ve organized all your channels by service level. So you can find what you want, when you want it. The New XFINITY Channel Lineup. It’s the faster way to find what you’re looking for. For more info, visit www.xfinity.com Prince George’s County, MD – Efective November 1, 2015 LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME WMDO-47 (uniMàs) 24 941 C-SPAN 23 Jewelry TV 200 WDCA Movies! 15/563 795 Washington DC WDCA-20 (MY) 104 942 C-SPAN2 184 Jewelry TV 20 810 Washington DC 269/559 WMPT V-me 287 Daystar 190 Leased Access WMPT-22 (PBS) 201 WDCW Antenna TV 22 812 72 Educational Access 76 Local Origination Annapolis 206 WDCW This TV 73 Educational Access 279 MHz Arirang 275 WNVC Bon-China WDCW-50 (CW) 3 803 MHz CCTV Washington DC 294 The Word Network 74 Educational Access 276 Documentary WPXW-66 (ION) 75 Educational Access 266 WETA Kids 16 813 273 MHz CCTV News Washington DC 265 WETA UK 77 Educational Access WQAW-20 (Azteca 278 MHz CNC World 198/568 WETA-26 (PBS) America) 78 Educational Access 26 800 277 MHz France 24 Washington DC 208 WRC Cozi TV 96 Educational Access WFDC-14 (Univision) 272 MHz NHK World TV 14/561 794 WRC-4 (NBC) Washington DC 4 804 89/283 EVINE Live Washington DC 274 MHz RT WHUT-32 (PBS) 19 802 291 799 EWTN Washington DC 197 WTTG Buzzr 280 MHz teleSUR 69 Gov’t Access WJLA Live Well WTTG-5 (FOX) 205 5 805 271 MHz Worldview Network Washington DC 70 Gov’t Access 268 MPT2 204 WJLA MeTV 207 WUSA Bounce TV 71 -

Chinese Public Diplomacy: the Rise of the Confucius Institute / Falk Hartig

Chinese Public Diplomacy This book presents the first comprehensive analysis of Confucius Institutes (CIs), situating them as a tool of public diplomacy in the broader context of China’s foreign affairs. The study establishes the concept of public diplomacy as the theoretical framework for analysing CIs. By applying this frame to in- depth case studies of CIs in Europe and Oceania, it provides in-depth knowledge of the structure and organisation of CIs, their activities and audiences, as well as problems, chal- lenges and potentials. In addition to examining CIs as the most prominent and most controversial tool of China’s charm offensive, this book also explains what the structural configuration of these Institutes can tell us about China’s under- standing of and approaches towards public diplomacy. The study demonstrates that, in contrast to their international counterparts, CIs are normally organised as joint ventures between international and Chinese partners in the field of educa- tion or cultural exchange. From this unique setting a more fundamental observa- tion can be made, namely China’s willingness to engage and cooperate with foreigners in the context of public diplomacy. Overall, the author argues that by utilising the current global fascination with Chinese language and culture, the Chinese government has found interested and willing international partners to co- finance the CIs and thus partially fund China’s international charm offensive. This book will be of much interest to students of public diplomacy, Chinese politics, foreign policy and international relations in general. Falk Hartig is a post-doctoral researcher at Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany, and has a PhD in Media & Communication from Queensland Univer- sity of Technology, Australia. -

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Asia

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia & Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Herzegonia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Congo Brazzaville, Congo Kinshasa, Egypt, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Hungary, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Moldova, Montenegro, The Netherlands, Norway, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Uganda, Western Sahara, Zambia. Armenia, Ukraine, United Kingdom. Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen. Asia & Pacific North & South America Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, United Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Macau, Maldives, Myanmar, States of America. Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Nepal, Pakistan, Phillipines, South Korea, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela. Uzbekistan, Vietnam. Australia, French Polynesia, New Zealand. EUROPE Albania Austria Belarus Belgium Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic France Germany Gibraltar Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

Internationalization, Regionalization, and Soft Power: China's Relations

Front. Educ. China 2012, 7(4): 486–507 DOI 10.3868/s110-001-012-0025-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE YANG Rui Internationalization, Regionalization, and Soft Power: China’s Relations with ASEAN Member Countries in Higher Education Abstract Since the late 1980s, there has been a resurgence of regionalism in world politics. Prospects for new alliances are opened up often on a regional basis. In East and Southeast Asia, regionalization is becoming evident in higher education, with both awareness and signs of a rising ASEAN+3 higher education community. The quest for regional influence in Southeast Asia, however, has not been immune from controversies. One fact has been China’s growing soft power. As a systematically planned soft power policy, China is projecting soft power actively through higher education in the region. Yet, China-ASEAN relations in higher education have been little documented. Unlike the mainstay of the practices of internationalization in higher education that focuses overwhelmingly on educational exchange and collaboration with affluent Western countries, China’s interactions with ASEAN member countries in higher education are fulfilled by “quiet achievers,” mainly seen at the regional institutions in relatively less developed provinces such as Guangxi and Yunnan. This article selects regional higher education institutions in China’s much disadvantaged provinces to depict a different picture to argue that regionalization could contribute substantially to internationalization, if a variety of factors are combined properly. Keywords internationalization, regionalization, soft power, China, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Introduction Resurgent regionalism in recent decades has created fresh challenges and prospects for new alliances (Hurrell, 1995; Jayasuriya, 2003). -

Shifting Economic Power1

Shifting Economic Power1 John Whalley University of Western Ontario Centre for International of Governance Innovation and CESifo Munich, Germany Abstract Here, I discuss both alternative meanings of shifting economic power and possible metrics which may be used to capture its quantitative dimensions. The third sense of power is very difficult to quantify. That economic power is shifting away from the OECD to rapidly growing low wage economies seems to be a consensus view. How to conceptualize and measure it is the task addressed here, although shifts in relative terms may not be occurring in the same way as in absolute terms. I focus on economic power both in its retaliatory and bargaining senses, as well as soft power in terms of intellectual climate and reputation. September 2009 1This is a first draft for an OECD Development Centre project on Shifting Global Wealth. It draws on earlier work by Antkiewicz & Whalley (2005). I am grateful to Helmut Riesen, Andrew Mold, Carlo Perroni, Shunming Zhang a referee, and Ray Riezman for discussions and comments, and Yan Dong and Huifang Tian for help with computations. 1. Introduction The pre- crisis prospect of continuing high GDP growth rates in and accelerating growth rates of exports from the large population economies of China and India combined with elevated growth in ASEAN, Russia, Brazil and South Africa (despite the recent global financial crisis) has lead to speculation that over the next few decades global economic power will progressively shift from the Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD) (specifically the US and the EU) to the non-OECD, and mainly to a group of large population rapidly growing economies which include Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, ASEAN, Turkey, Egypt and Nigeria.2 With this shift in power, the conjecture is that the global economy will undergo a major regime shift as global architecture and rules, trade patterns, and foreign direct investment (FDI) flows all adapt and change.