The Globalization of Chinese News Programs: a Country of Origin Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Soft Power in East Asia

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #42 | january 2013 china’s soft power in east asia A Quest for Status and Influence? By Chin-Hao Huang cover 2 The NBR Special Report provides access to current research on special topics conducted by the world’s leading experts in Asian affairs. The views expressed in these reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of other NBR research associates or institutions that support NBR. The National Bureau of Asian Research is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research institution dedicated to informing and strengthening policy. NBR conducts advanced independent research on strategic, political, economic, globalization, health, and energy issues affecting U.S. relations with Asia. Drawing upon an extensive network of the world’s leading specialists and leveraging the latest technology, NBR bridges the academic, business, and policy arenas. The institution disseminates its research through briefings, publications, conferences, Congressional testimony, and email forums, and by collaborating with leading institutions worldwide. NBR also provides exceptional internship opportunities to graduate and undergraduate students for the purpose of attracting and training the next generation of Asia specialists. NBR was started in 1989 with a major grant from the Henry M. Jackson Foundation. Funding for NBR’s research and publications comes from foundations, corporations, individuals, the U.S. government, and from NBR itself. NBR does not conduct proprietary or classified research. The organization undertakes contract work for government and private-sector organizations only when NBR can maintain the right to publish findings from such work. To download issues of the NBR Special Report, please visit the NBR website http://www.nbr.org. -

New Media in New China

NEW MEDIA IN NEW CHINA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEMOCRATIZING EFFECT OF THE INTERNET __________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, East Bay __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Communication __________________ By Chaoya Sun June 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Chaoya Sun ii NEW MEOlA IN NEW CHINA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEMOCRATIlING EFFECT OF THE INTERNET By Chaoya Sun III Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 PART 1 NEW MEDIA PROMOTE DEMOCRACY ................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 THE COMMUNICATION THEORY OF HAROLD INNIS ........................................ 10 NEW MEDIA PUSH ON DEMOCRACY .................................................................... 13 Offering users the right to choose information freely ............................................... 13 Making free-thinking and free-speech available ....................................................... 14 Providing users more participatory rights ................................................................. 15 THE FUTURE OF DEMOCRACY IN THE CONTEXT OF NEW MEDIA ................ 16 PART 2 2008 IN RETROSPECT: FRAGILE CHINESE MEDIA UNDER THE SHADOW OF CHINA’S POLITICS ........................................................................... -

The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship: How the Communist Party’S Media Restrictions Affect News Outlets Around the World

The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship: How the Communist Party’s Media Restrictions Affect News Outlets Around the World A Report to the Center for International Media Assistance By Sarah Cook October 22, 2013 The Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA), at the National Endowment for Democracy, works to strengthen the support, raise the visibility, and improve the effectiveness of independent media development throughout the world. The Center provides information, builds networks, conducts research, and highlights the indispensable role independent media play in the creation and development of sustainable democracies. An important aspect of CIMA’s work is to research ways to attract additional U.S. private sector interest in and support for international media development. CIMA convenes working groups, discussions, and panels on a variety of topics in the field of media development and assistance. The center also issues reports and recommendations based on working group discussions and other investigations. These reports aim to provide policymakers, as well as donors and practitioners, with ideas for bolstering the effectiveness of media assistance. Don Podesta Interim Senior Director Center for International Media Assistance National Endowment for Democracy 1025 F Street, N.W., 8th Floor Washington, DC 20004 Phone: (202) 378-9700 Fax: (202) 378-9407 Email: [email protected] URL: http://cima.ned.org Design and Layout by Valerie Popper About the Author Sarah Cook Sarah Cook is a senior research analyst for East Asia at Freedom House. She manages the editorial team producing the China Media Bulletin, a biweekly news digest of media freedom developments related to the People’s Republic of China. -

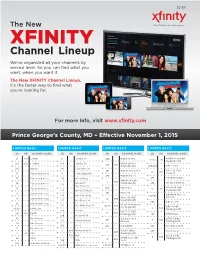

XFINITY Channel Lineup We’Ve Organized All Your Channels by Service Level

2C-307 The New XFINITY Channel Lineup We’ve organized all your channels by service level. So you can find what you want, when you want it. The New XFINITY Channel Lineup. It’s the faster way to find what you’re looking for. For more info, visit www.xfinity.com Prince George’s County, MD – Efective November 1, 2015 LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC LIMITED BASIC SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME SD HD CHANNEL NAME WMDO-47 (uniMàs) 24 941 C-SPAN 23 Jewelry TV 200 WDCA Movies! 15/563 795 Washington DC WDCA-20 (MY) 104 942 C-SPAN2 184 Jewelry TV 20 810 Washington DC 269/559 WMPT V-me 287 Daystar 190 Leased Access WMPT-22 (PBS) 201 WDCW Antenna TV 22 812 72 Educational Access 76 Local Origination Annapolis 206 WDCW This TV 73 Educational Access 279 MHz Arirang 275 WNVC Bon-China WDCW-50 (CW) 3 803 MHz CCTV Washington DC 294 The Word Network 74 Educational Access 276 Documentary WPXW-66 (ION) 75 Educational Access 266 WETA Kids 16 813 273 MHz CCTV News Washington DC 265 WETA UK 77 Educational Access WQAW-20 (Azteca 278 MHz CNC World 198/568 WETA-26 (PBS) America) 78 Educational Access 26 800 277 MHz France 24 Washington DC 208 WRC Cozi TV 96 Educational Access WFDC-14 (Univision) 272 MHz NHK World TV 14/561 794 WRC-4 (NBC) Washington DC 4 804 89/283 EVINE Live Washington DC 274 MHz RT WHUT-32 (PBS) 19 802 291 799 EWTN Washington DC 197 WTTG Buzzr 280 MHz teleSUR 69 Gov’t Access WJLA Live Well WTTG-5 (FOX) 205 5 805 271 MHz Worldview Network Washington DC 70 Gov’t Access 268 MPT2 204 WJLA MeTV 207 WUSA Bounce TV 71 -

Chinese Public Diplomacy: the Rise of the Confucius Institute / Falk Hartig

Chinese Public Diplomacy This book presents the first comprehensive analysis of Confucius Institutes (CIs), situating them as a tool of public diplomacy in the broader context of China’s foreign affairs. The study establishes the concept of public diplomacy as the theoretical framework for analysing CIs. By applying this frame to in- depth case studies of CIs in Europe and Oceania, it provides in-depth knowledge of the structure and organisation of CIs, their activities and audiences, as well as problems, chal- lenges and potentials. In addition to examining CIs as the most prominent and most controversial tool of China’s charm offensive, this book also explains what the structural configuration of these Institutes can tell us about China’s under- standing of and approaches towards public diplomacy. The study demonstrates that, in contrast to their international counterparts, CIs are normally organised as joint ventures between international and Chinese partners in the field of educa- tion or cultural exchange. From this unique setting a more fundamental observa- tion can be made, namely China’s willingness to engage and cooperate with foreigners in the context of public diplomacy. Overall, the author argues that by utilising the current global fascination with Chinese language and culture, the Chinese government has found interested and willing international partners to co- finance the CIs and thus partially fund China’s international charm offensive. This book will be of much interest to students of public diplomacy, Chinese politics, foreign policy and international relations in general. Falk Hartig is a post-doctoral researcher at Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany, and has a PhD in Media & Communication from Queensland Univer- sity of Technology, Australia. -

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Asia

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia & Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Herzegonia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Congo Brazzaville, Congo Kinshasa, Egypt, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Hungary, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Moldova, Montenegro, The Netherlands, Norway, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Uganda, Western Sahara, Zambia. Armenia, Ukraine, United Kingdom. Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen. Asia & Pacific North & South America Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, United Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Macau, Maldives, Myanmar, States of America. Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Nepal, Pakistan, Phillipines, South Korea, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela. Uzbekistan, Vietnam. Australia, French Polynesia, New Zealand. EUROPE Albania Austria Belarus Belgium Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic France Germany Gibraltar Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

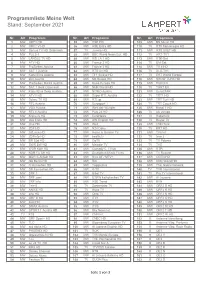

Programmliste Meine Welt Stand: August 2021

Programmliste Meine Welt Stand: September 2021 Nr. Art Programm Nr. Art Programm Nr. Art Programm 1 MW ORF1 HD 55 MW HSE HD 109 MW BN Music HD 2 MW ORF2 V HD 56 MW HSE Extra HD 110 TV RTV Montenegro HD 3 MW Servus TV HD Österreich 57 TV Juwelo HD 111 MW RTS SVET HD 4 MW PULS 4 58 MW BBC World News Eur. HD 112 TV HRT-TV1 5 MW LÄNDLE TV HD 59 MW RSI LA 1 HD 113 MW RTK-Sat 6 MW ATV HD 60 MW France 2 HD 114 TV DM-Sat 7 MW ProSieben Austria 61 MW France 3 HD 115 MW TV 8 HD 8 MW SAT.1 Austria 62 MW RTS Un HD 116 TV SLO-TV1 9 MW Kabel Eins Austria 63 MW TF1 Suisse HD 117 TV ERT World Europe 10 MW sixx Austria 64 MW M6 Suisse HD 118 MW SHOW TURK HD 11 MW ProSieben MAXX Austria 65 MW Duna Europa HD 119 MW EURO D 12 MW SAT.1 Gold Österreich 66 MW NHK World HD 120 TV TGRT EU 13 MW Kabel Eins Doku Austria 67 MW NITRO Austria 121 MW EuroSTAR 14 MW ATV ll HD 68 MW Super RTL Austria 122 TV TRT1 HD 15 MW Schau TV HD 69 MW RTLup 123 MW TRT Turk HD 16 MW RTL Austria 70 MW Eurosport 1 124 TV TRT Cocuk HD 17 MW VOX Austria 71 MW Welt der Wunder 125 MW Kanal 7 HD 18 MW RTL ll Austria 72 MW Puls 24 HD 126 TV atv avrupa 19 MW Krone.tv HD 73 MW EuroNews 127 TV Haberturk 20 MW Das Erste HD 74 MW DW English HD 128 TV Beyaz TV 21 MW One HD 75 MW Welt 129 MW CNN Turk 22 MW ZDF HD 76 MW N24 Doku 130 TV KRT HD 23 MW zdf_neo HD 77 MW Home & Garden TV 131 MW TV8 Int. -

Student Report Notebook Kit (Cover, Binder Spine, Divider Tabs)

School of Contemporary Chinese Studies China Policy Institute WORKING PAPER SERIES How Ready is China for a China-style World Order? China’s state media discourse under construction Xiaoling Zhang WorkingWP No.2012 Paper-01 No. 8 January 2013 How ready is China for a China-style world order? China’s state media discourse under construction Abstract What is exactly a China-style world order that Chinese officials and intellectual elites have been recently talking about, and how ready is China for it? An examination of the discourses by major state media for the promotion of China’s voice and image abroad, contextualized and enhanced by extensive in-depth interviews, confirms that although China has shifted from the low-profile approach to a more assertive one wanting to change the global order, its verbal challenge and sometimes harsh criticism of the US-led international system is accompanied by an obvious absence of a clear vision of what the new world order should be like. This lack of a clear vision, this paper argues, is due to the fact that the Chinese discourse on world order is still work-in-progress, constrained by internal practices, and Africa is its testing ground for the construction of a discourse that China hopes to be an alternative. Keywords International community, state media discourse, Sino-African relations, testing ground Xiaoling Zhang University of Nottingham School of Contemporary Chinese Studies Email: [email protected] Publication in the CPI Working Papers series does not imply views thus expressed are endorsed or supported by the China Policy Institute or the School of Contemporary Chinese Studies at the University of Nottingham. -

Temecula Valley Balloon & Wine Festival 2014 Entry BEST MEDIA

Temecula Valley Balloon & Wine Festival 2014 Entry BEST MEDIA RELATIONS CAMPAIGN #61 1. OVERVIEW A. Introduction & Background of Campaign/Event: Celebrating 31 years of beautiful hot air balloon launches at dawn, stunning evening balloon glows, world renowned musical entertainment in concert, wine tasting, food and wine pairings and family entertainment. The Temecula Valley Balloon & Wine Festival has branded the Temecula Valley as the place with "the Balloon and Wine Festival" and is one of the highest attended events in Southern California. Located on the border of San Diego and Riverside Counties, the Festival has an enormous pool of media within its reach, with three very large demographic market areas. These areas include Los Angeles/Orange County, Riverside/San Bernardino and San Diego. Major media offices are located anywhere from 40 minutes to 2 hours from our Festival site. Each year our challenge is to provide something "new" and exciting, that can entice the producers, editors, and photojournalists to take the drive to our Festival for live coverage, while providing pre-event publicity in the weeks and months prior to the event. Following the 30th Anniversary and experiencing a decline in the number of print media, we had additional challenges and focused our attention on the visual beauty of the balloons in flight. B. Purpose/Objective of the Media Relations Campaign: The purpose of the media relations campaign is to increase event awareness and attendance, while improving sponsor and event partner marketing benefits and engagement. To do this, data from event surveys and attendance profiles were analyzed and matched to media outlets and contacts for their interests and audience demographics. -

Aiddata, College of William & Mary)

AAI ReseaDrch LabD at WAilliamT & AMary Intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Brooke Russell, Matthew DiLorenzo, Mengfan Cheng, Siddhartha Ghose, Harsh Desai, Jacob Sims, and Jennifer Turner (AidData, College of William & Mary). The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders, partners, and advisors we thank below. The broader study was conducted in collaboration with Brad Parks (AidData, College of William & Mary), Debra Eisenman, Lindsey Ford, and Trisha Ray (Asia Society Policy Institute), and Bonnie Glaser (Center for Strategic and International Studies) who provided invaluable guidance throughout the entire process of research design, data collection, analysis, and report drafting. John Custer and Borah Kim (AidData, College of William & Mary) were integral to the editing, formatting, layout and visuals for this report. The authors thank the following external scholars and experts for their insightful feedback on the research design and early versions of our taxonomy of public diplomacy, including: Nicholas Cull (University of Southern California), Andreas Fuchs (Helmut Schmidt University Hamburg and the Kiel Institute for World Economy), John L. Holden (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), John Holden (Demos), Markos Kounalakis (Washington Monthly), Shawn Powers (United States Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy), Ambassador William Rugh (Tufts University), Austin Strange (Harvard University), and Jian (Jay) Wang, (University of Southern California). We owe a debt of gratitude to the 76 government officials, civil society and private sector leaders, academics, journalists, and foreign diplomats who graciously participated in key informant interviews and answered our questions on the state of Chinese public diplomacy in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Fiji. -

2013 China Marketing Trip Fleishmanhillard

2013 China Marketing Trip FleishmanHillard As of August 13, 2013 Table of Contents Section I Trip Overview ........................................................................................................................ 3 Section II Competitive Analysis .......................................................................................................... 11 Overall Observations ............................................................................................................................. 12 Top 20 PR Firms in China ....................................................................................................................... 13 Ownerships ............................................................................................................................................ 14 Burson-Marsteller .................................................................................................................................. 15 Ogilvy & Mather .................................................................................................................................... 18 Weber Shandwick .................................................................................................................................. 21 Edelman ................................................................................................................................................. 23 APCO .....................................................................................................................................................