Tracking a Northern Fulmar from a Scottish Nesting Site to the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone Evidence of Linkage Between Coastal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012

SCOTTISH NATURAL HERITAGE TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012 SEABIRDS IN SCOTLAND Prepared by Simon Foster and Sue Marrs of SNH Knowledge Information Management Unit using results from the Seabird Monitoring Programme and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Scotland has internationally important populations of several seabirds. Their conservation is assisted through a network of designated sites. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 50 Special Protection Areas (SPA) which have seabirds listed as a feature of interest. The map shows the widespread nature of the sites and the predominance of important seabird areas on the Northern Isles (Orkney and Shetland), where some of our largest seabird colonies are present. The most recent estimate of seabird populations was obtained from Birds of Scotland (Forrester et al., 2007). Table 1 shows the population levels for all seabirds regularly breeding in Scotland. Table 1: Population Estimates for Breeding Seabirds in Scotland. Figure 1: Special Protection Areas for Seabirds Breeding in Scotland. Species* Unit** Estimate Key Points Northern fulmar 486,000 AOS Manx shearwater 126,545 AOS Trends are described for 11 of the 24 European storm-petrel 31,570+ AOS species of seabirds breeding in Leach’s storm-petrel 48,057 AOS Scotland Northern gannet 182,511 AOS Great cormorant c. 3,600 AON Nine have shown sustained declines European shag 21,500-30,000 PAIRS over the past 20 years. Two have Arctic skua 2,100 AOT remained stable. Great skua 9,650 AOT The reasons for the declines are Black headed -

Copulation and Mate Guarding in the Northern Fulmar

COPULATION AND MATE GUARDING IN THE NORTHERN FULMAR SCOTT A. HATCH Museumof VertebrateZoology, University of California,Berkeley, California 94720 USA and AlaskaFish and WildlifeResearch Center, U.S. Fish and WildlifeService, 1011 East Tudor Road, Anchorage,Alaska 99503 USA• ABSTRACT.--Istudied the timing and frequency of copulation in mated pairs and the occurrenceof extra-paircopulation (EPC) among Northern Fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis) for 2 yr. Copulationpeaked 24 days before laying, a few daysbefore females departed on a prelaying exodus of about 3 weeks. I estimated that females were inseminated at least 34 times each season.A total of 44 EPC attemptswas seen,9 (20%)of which apparentlyresulted in insem- ination.Five successful EPCs were solicitated by femalesvisiting neighboring males. Multiple copulationsduring a singlemounting were rare within pairsbut occurredin nearly half of the successfulEPCs. Both sexesvisited neighborsduring the prelayingperiod, and males employed a specialbehavioral display to gain acceptanceby unattended females.Males investedtime in nest-siteattendance during the prelaying period to guard their matesand pursueEPC. However, the occurrenceof EPC in fulmars waslargely a matter of female choice. Received29 September1986, accepted 16 February1987. THEoccurrence and significanceof extra-pair Bjorkland and Westman 1983; Buitron 1983; copulation (EPC) in monogamousbirds has Birkhead et al. 1985). generated much interest and discussion(Glad- I attemptedto documentthe occurrenceand stone 1979; Oring 1982; Ford 1983; McKinney behavioral contextof extra-pair copulationand et al. 1983, 1984). Becausethe males of monog- mate guarding in a colonial seabird,the North- amous species typically make a large invest- ern Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis). Fulmars are ment in the careof eggsand young, the costof among the longest-lived birds known, and fi- being cuckolded is high, as are the benefits to delity to the same mate and nest site between the successfulcuckolder. -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

Geographic Variation in Leach's Storm-Petrel

GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN LEACH'S STORM-PETREL DAVID G. AINLEY Point Reyes Bird Observatory, 4990 State Route 1, Stinson Beach, California 94970 USA ABSTRACT.-•A total of 678 specimens of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) from known nestinglocalities was examined, and 514 were measured. Rump color, classifiedon a scale of 1-11 by comparison with a seriesof reference specimens,varied geographicallybut was found to be a poor character on which to base taxonomic definitions. Significant differences in five size charactersindicated that the presentlyaccepted, but rather confusing,taxonomy should be altered: (1) O. l. beali, O. l. willetti, and O. l. chapmani should be merged into O. l. leucorhoa;(2) O. l. socorroensisshould refer only to the summer breeding population on Guadalupe Island; and (3) the winter breeding Guadalupe population should be recognizedas a "new" subspecies,based on physiological,morphological, and vocal characters,with the proposedname O. l. cheimomnestes. The clinal and continuoussize variation in this speciesis related to oceanographicclimate, length of migration, mobility during the nesting season,and distancesbetween nesting islands. Why oceanitidsfrequenting nearshore waters during nestingare darker rumped than thoseoffshore remains an unanswered question, as does the more basic question of why rump color varies geographicallyin this species.Received 15 November 1979, accepted5 July 1980. DURING field studies of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) nesting on Southeast Farallon Island, California in 1972 and 1973 (see Ainley et al. 1974, Ainley et al. 1976), several birds were captured that had dark or almost completely dark rumps. The subspecificidentity of the Farallon population, which at that time was O. -

SEAPOP Studies in the Lofoten and Barents Sea Area in 2006

249 SEAPOP studies in the Lofoten and Barents Sea area in 2006 Tycho Anker-Nilssen Robert T. Barrett Jan Ove Bustnes Kjell Einar Erikstad Per Fauchald Svein-Håkon Lorentsen Harald Steen Hallvard Strøm Geir Helge Systad Torkild Tveraa NINA Publications NINA Report (NINA Rapport) This is a new, electronic series beginning in 2005, which replaces the earlier series NINA commissioned reports and NINA project reports. This will be NINA’s usual form of reporting completed research, monitoring or review work to clients. In addition, the series will include much of the institute’s other reporting, for example from seminars and conferences, results of internal research and review work and literature studies, etc. NINA report may also be issued in a second language where appropriate. NINA Special Report (NINA Temahefte) As the name suggests, special reports deal with special subjects. Special reports are produced as required and the series ranges widely: from systematic identification keys to information on important problem areas in society. NINA special reports are usually given a popular scientific form with more weight on illustrations than a NINA report. NINA Factsheet (NINA Fakta) Factsheets have as their goal to make NINA’s research results quickly and easily accessible to the general public. The are sent to the press, civil society organisations, nature management at all levels, politicians, and other special interests. Fact sheets give a short presentation of some of our most important research themes. Other publishing In addition to reporting in NINA’s own series, the institute’s employees publish a large proportion of their scientific results in international journals, popular science books and magazines. -

Fulmarus Glacialis

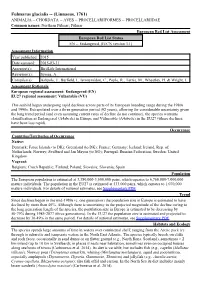

Fulmarus glacialis -- (Linnaeus, 1761) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PROCELLARIIFORMES -- PROCELLARIIDAE Common names: Northern Fulmar; Fulmar European Red List Assessment European Red List Status EN -- Endangered, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Tarzia, M., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Endangered (EN) EU27 regional assessment: Vulnerable (VU) This seabird began undergoing rapid declines across parts of its European breeding range during the 1980s and 1990s. Extrapolated over a three generation period (92 years), allowing for considerable uncertainty given the long trend period (and even assuming current rates of decline do not continue), the species warrants classification as Endangered (A4abcde) in Europe and Vulnerable (A4abcde) in the EU27 (where declines have been less rapid). Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Denmark; Faroe Islands (to DK); Greenland (to DK); France; Germany; Iceland; Ireland, Rep. of; Netherlands; Norway; Svalbard and Jan Mayen (to NO); Portugal; Russian Federation; Sweden; United Kingdom Vagrant: Belgium; Czech Republic; Finland; Poland; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain Population The European population is estimated at 3,380,000-3,500,000 pairs, which equates to 6,760,000-7,000,000 mature individuals. The population in the EU27 is estimated at 533,000 pairs, which equates to 1,070,000 mature individuals. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Trend Since declines began in the mid-1980s (c. one generation) the population size in Europe is estimated to have declined by more than 40%. -

NORTHERN FULMAR Fulmarus Glacialis Non-Breeding Visitor, Occasional Winterer F.G

NORTHERN FULMAR Fulmarus glacialis non-breeding visitor, occasional winterer F.g. rodgersii Northern Fulmars breed throughout the Holarctic and winter irregularly south to temperate Pacific and Atlantic waters (Dement'ev and Gladkov 1951a, Cramp and Simmons 1977, Harrison 1983, AOU 1998). They occasionally reach the Hawaiian region in Nov-Mar, with most records being of birds found weak or dead on shore. In the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, remains of 18 individuals have been found (Clapp and Woodward 1968, Woodward 1972, Zeillemaker 1976), on Kure (4, 1976- 1978; USNM 498110-112, 492919; HRBP 0017, 0040); Midway (9, 1962-1996; e.g., USNM 478860, 498113-114; BPBM 178503, 183500, 184419); Pearl and Hermes Reef 6 Apr 1976; and French Frigate 25 Jun 1923 (USNM 489327). Many specimens were old and dry, with fresher ones being collected between late Dec and mid Mar. Individuals were also observed from shore at Midway 8-10 Dec 1959 and 16 Dec 1962 (Fisher 1965); a light-morph bird reported from Midway 5 Sep 2007 would be very early and may have been of a gull. In the Southeastern Hawaiian Islands, one found alive but with a broken neck on Larson's Beach, Kaua'i, 3 Mar 2004 was photographed (HRBP 5029) and later died (BPBM 185188). On O'ahu, weak or dead birds were found on Waimanalo Beach 17 Feb 1959 (King 1959a); Kailua Beach 18 Nov 1983 (USNM 614986), 5 Dec 1987 (HRBP 0725-0727; BPBM 175993), 15 Jan 1989 (HRBP 0914-0915; BPBM 177891), and 17 Nov 2008 (HRBP 5443-5444; BPBM); and in Honolulu 23 March 1998 (BPBM 184115). -

Partial Migration in the Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates Pelagicus Melitensis

Lago et al.: Partial migration in Mediterranean Storm Petrel 105 PARTIAL MIGRATION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN STORM PETREL HYDROBATES PELAGICUS MELITENSIS PAULO LAGO*, MARTIN AUSTAD & BENJAMIN METZGER BirdLife Malta, 57/28 Triq Abate Rigord, Ta’ Xbiex XBX 1120, Malta *([email protected]) Received 27 November 2018, accepted 05 February 2019 ABSTRACT LAGO, P., AUSTAD, M. & METZGER, B. 2019. Partial migration in the Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. Marine Ornithology 47: 105–113. Studying the migration routes and wintering areas of seabirds is crucial to understanding their ecology and to inform conservation efforts. Here we present results of a tracking study carried out on the little-known Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. During the 2016 breeding season, Global Location Sensor (GLS) tags were deployed on birds at the largest Mediterranean colony: the islet of Filfla in the Maltese Archipelago. The devices were retrieved the following season, revealing hitherto unknown movements and wintering areas of this species. Most individuals remained in the Mediterranean throughout the year, with birds shifting westwards or remaining in the central Mediterranean during winter. However, one bird left the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar and wintered in the North Atlantic. Our results from GLS tracking, which are supported by data from ringed and recovered birds, point toward a system of partial migration with high inter-individual variation. This highlights the importance of trans-boundary marine protection for the conservation of vulnerable seabirds. Key words: Procellariformes, movement, geolocation, wintering, Malta, capture-mark-recovery INTRODUCTION The Mediterranean Storm Petrel has been described as sedentary, because birds are present in their breeding areas throughout the year The Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis is (Zotier et al. -

1. (1.00 Pts) the Bird Shown in Image 1 Belongs to What Species? A

B - Ornithology B November - Nov 7 Country-wide SO Practice - 11-07-2020 For multiple-choice questions, choose the BEST answer. For Fill-in-the Blank questions, complete the sentence by filling in the blank with the most accurate word or name. 1. (1.00 pts) The bird shown in Image 1 belongs to what species? A) Northern Bobwhite B) Rock Pigeon C) Northern Fulmar D) California Quail 2. (1.00 pts) The structure jutting from the "forehead" of the bird in Image 1 is called a crest or ______________________________. plume 3. (1.00 pts) The bird shown in Image 2 belongs to what species? A) Killdeer B) American Golden Plover C) Ring-Necked Pheasant D) American Woodcock 4. (1.00 pts) The bird shown in Image 3 belongs to what species? A) Turkey Vulture B) Wild Turkey C) Ruffed Grouse D) Northern Fulmar 5. (1.00 pts) Of the three species in Images 1, 2, and 3, which is most widespread in the United States? A) The species shown in Image 1 B) The species shown in Image 2 C) The species shown in Image 3 D) The species in both Images 1 and 2 are equally widespread. 6. (1.00 pts) . The bird shown in Image 4 belongs to what species? A) Eastern Bluebird B) Blue Jay C) Indigo Bunting D) Purple Gallinule 7. (1.00 pts) . The bird shown in Image 5 belongs to what species? A) Eastern Bluebird B) Stellers Jay C) Indigo Bunting D) Verdin 8. (1.00 pts) . The bird shown in Image 6 belongs to what species? A) Purple Gallinule B) Stellers Jay C) Purple Martin D) Black-Billed Magpie 9. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

<I>Fulmarus Glacialis</I>, Breeding in Newfoundland <Sup>

The Northern Fulmar,Fulmarus glacialis, breedingin NewfoundlandI DavidN. Nettleship:and R. D. Montgomerie3 The Northern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis, is a comm.),but nestingwas not established.The fact b•rd of the openocean, known to breedin North that the Witless Bay islands, and in particular America only in Alaska, the Canadian Arctic, Great Island, are amongthe mostclosely studied and Greenland. Godfrey (1%6) notes that it seabirdislands in easternCanada suggeststhat nests in large coloniesin the Canadian arctic this colony on Great Island is of recent origin, islands and is "found in summer in many other especiallyas Nettleship did not find breeding partsof the CanadianArctic westto BanksIsland fulmarsduring his seabirdstudies there between (rarely),north to EllesmereIsland, and commonly 1967 and 1969 (Nettleship,1972). It also seems southward to waters off Newfoundland, but not likely that this southwardexpansion into temper- Hudson Bay." Although one of the commonest ate North American waters is related to the in- b•rds at sea off Labrador from late April to early creaseof boreal nestingfulmars noted through- October (Austin, 1932; Todd, 1%3) and regular out the species'North Atlantic range (Fisher, off Newfoundlandthroughout the year (Peters 1952; Salomonsen,1965). and Burleigh,1951; Tuck, 1%7) it has not pre- Attempts shouldbe made to revisit the site viouslybeen found breeding in theseregions. systematicallyin the futureto providesome docu- BetweenJuly 23 and 29, 1973 during a census mentationof the colonizingprocess. of breeding seabirdsin Witless Bay, Newfound- LITERATURE CITED land, Montgomeriefound 6 fulmar nests,all of which containedyoung, on the northwestcorner Austin, O. L. 1932. The birds of Newfoundland Labra- of Great Island (47ø11'N, 52ø49'W), located off dor.