Observations on the Diving Behavior of the Northern Fulmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012

SCOTTISH NATURAL HERITAGE TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012 SEABIRDS IN SCOTLAND Prepared by Simon Foster and Sue Marrs of SNH Knowledge Information Management Unit using results from the Seabird Monitoring Programme and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Scotland has internationally important populations of several seabirds. Their conservation is assisted through a network of designated sites. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 50 Special Protection Areas (SPA) which have seabirds listed as a feature of interest. The map shows the widespread nature of the sites and the predominance of important seabird areas on the Northern Isles (Orkney and Shetland), where some of our largest seabird colonies are present. The most recent estimate of seabird populations was obtained from Birds of Scotland (Forrester et al., 2007). Table 1 shows the population levels for all seabirds regularly breeding in Scotland. Table 1: Population Estimates for Breeding Seabirds in Scotland. Figure 1: Special Protection Areas for Seabirds Breeding in Scotland. Species* Unit** Estimate Key Points Northern fulmar 486,000 AOS Manx shearwater 126,545 AOS Trends are described for 11 of the 24 European storm-petrel 31,570+ AOS species of seabirds breeding in Leach’s storm-petrel 48,057 AOS Scotland Northern gannet 182,511 AOS Great cormorant c. 3,600 AON Nine have shown sustained declines European shag 21,500-30,000 PAIRS over the past 20 years. Two have Arctic skua 2,100 AOT remained stable. Great skua 9,650 AOT The reasons for the declines are Black headed -

Copulation and Mate Guarding in the Northern Fulmar

COPULATION AND MATE GUARDING IN THE NORTHERN FULMAR SCOTT A. HATCH Museumof VertebrateZoology, University of California,Berkeley, California 94720 USA and AlaskaFish and WildlifeResearch Center, U.S. Fish and WildlifeService, 1011 East Tudor Road, Anchorage,Alaska 99503 USA• ABSTRACT.--Istudied the timing and frequency of copulation in mated pairs and the occurrenceof extra-paircopulation (EPC) among Northern Fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis) for 2 yr. Copulationpeaked 24 days before laying, a few daysbefore females departed on a prelaying exodus of about 3 weeks. I estimated that females were inseminated at least 34 times each season.A total of 44 EPC attemptswas seen,9 (20%)of which apparentlyresulted in insem- ination.Five successful EPCs were solicitated by femalesvisiting neighboring males. Multiple copulationsduring a singlemounting were rare within pairsbut occurredin nearly half of the successfulEPCs. Both sexesvisited neighborsduring the prelayingperiod, and males employed a specialbehavioral display to gain acceptanceby unattended females.Males investedtime in nest-siteattendance during the prelaying period to guard their matesand pursueEPC. However, the occurrenceof EPC in fulmars waslargely a matter of female choice. Received29 September1986, accepted 16 February1987. THEoccurrence and significanceof extra-pair Bjorkland and Westman 1983; Buitron 1983; copulation (EPC) in monogamousbirds has Birkhead et al. 1985). generated much interest and discussion(Glad- I attemptedto documentthe occurrenceand stone 1979; Oring 1982; Ford 1983; McKinney behavioral contextof extra-pair copulationand et al. 1983, 1984). Becausethe males of monog- mate guarding in a colonial seabird,the North- amous species typically make a large invest- ern Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis). Fulmars are ment in the careof eggsand young, the costof among the longest-lived birds known, and fi- being cuckolded is high, as are the benefits to delity to the same mate and nest site between the successfulcuckolder. -

The Taxonomy of the Procellariiformes Has Been Proposed from Various Approaches

山 階 鳥 研 報(J. Yamashina Inst. Ornithol.),22:114-23,1990 Genetic Divergence and Relationships in Fifteen Species of Procellariiformes Nagahisa Kuroda*, Ryozo Kakizawa* and Masayoshi Watada** Abstract The genetic analysis of 23 protein loci in 15 species of Procellariiformes was made The genetic distancesbetween the specieswas calculatedand a dendrogram was formulated of the group. The separation of Hydrobatidae from all other taxa including Diomedeidae agrees with other precedent works. The resultsof the present study support the basic Procellariidclassification system. However, two points stillneed further study. The firstpoint is that Fulmarus diverged earlier from the Procellariidsthan did the Diomedeidae. The second point is the position of Puffinuspacificus which appears more closely related to the Pterodroma petrels than to other Puffinus species. These points are discussed. Introduction The taxonomy of the Procellariiformes has been proposed from various approaches. The earliest study by Forbes (1882) was made by appendicular myology. Godman (1906) and Loomis (1918) studied this group from a morphological point of view. The taxonomy of the Procellariiformes by functional osteology and appendicular myology was studied by Kuroda (1954, 1983) and Klemm (1969), The results of the various studies agreed in proposing four families of Procellariiformes: Diomedeidae, Procellariidae, Hydrobatidae, and Pelecanoididae. They also pointed out that the Procellariidae was a heterogenous group among them. Timmermann (1958) found the parallel evolution of mallophaga and their hosts in Procellariiformes. Recently, electrophoretical studies have been made on the Procellariiformes. Harper (1978) found different patterns of the electromorph among the families. Bar- rowclough et al. (1981) studied genetic differentiation among 12 species of Procellari- iformes at 16 loci, and discussed the genetic distances among the taxa but with no consideration of their phylogenetic relationships. -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

Geographic Variation in Leach's Storm-Petrel

GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN LEACH'S STORM-PETREL DAVID G. AINLEY Point Reyes Bird Observatory, 4990 State Route 1, Stinson Beach, California 94970 USA ABSTRACT.-•A total of 678 specimens of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) from known nestinglocalities was examined, and 514 were measured. Rump color, classifiedon a scale of 1-11 by comparison with a seriesof reference specimens,varied geographicallybut was found to be a poor character on which to base taxonomic definitions. Significant differences in five size charactersindicated that the presentlyaccepted, but rather confusing,taxonomy should be altered: (1) O. l. beali, O. l. willetti, and O. l. chapmani should be merged into O. l. leucorhoa;(2) O. l. socorroensisshould refer only to the summer breeding population on Guadalupe Island; and (3) the winter breeding Guadalupe population should be recognizedas a "new" subspecies,based on physiological,morphological, and vocal characters,with the proposedname O. l. cheimomnestes. The clinal and continuoussize variation in this speciesis related to oceanographicclimate, length of migration, mobility during the nesting season,and distancesbetween nesting islands. Why oceanitidsfrequenting nearshore waters during nestingare darker rumped than thoseoffshore remains an unanswered question, as does the more basic question of why rump color varies geographicallyin this species.Received 15 November 1979, accepted5 July 1980. DURING field studies of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) nesting on Southeast Farallon Island, California in 1972 and 1973 (see Ainley et al. 1974, Ainley et al. 1976), several birds were captured that had dark or almost completely dark rumps. The subspecificidentity of the Farallon population, which at that time was O. -

Bugoni 2008 Phd Thesis

ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF ALBATROSSES AND PETRELS AT SEA OFF BRAZIL Leandro Bugoni Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, at the Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow. July 2008 DECLARATION I declare that the work described in this thesis has been conducted independently by myself under he supervision of Professor Robert W. Furness, except where specifically acknowledged, and has not been submitted for any other degree. This study was carried out according to permits No. 0128931BR, No. 203/2006, No. 02001.005981/2005, No. 023/2006, No. 040/2006 and No. 1282/1, all granted by the Brazilian Environmental Agency (IBAMA), and International Animal Health Certificate No. 0975-06, issued by the Brazilian Government. The Scottish Executive - Rural Affairs Directorate provided the permit POAO 2007/91 to import samples into Scotland. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was very lucky in having Prof. Bob Furness as my supervisor. He has been very supportive since before I had arrived in Glasgow, greatly encouraged me in new initiatives I constantly brought him (and still bring), gave me the freedom I needed and reviewed chapters astonishingly fast. It was a very productive professional relationship for which I express my gratitude. Thanks are also due to Rona McGill who did a great job in analyzing stable isotopes and teaching me about mass spectrometry and isotopes. Kate Griffiths was superb in sexing birds and explaining molecular methods again and again. Many people contributed to the original project with comments, suggestions for the chapters, providing samples or unpublished information, identifyiyng fish and squids, reviewing parts of the thesis or helping in analysing samples or data. -

Southern Fulmar

SOUTHERN FULMAR Fulmarus glacialoides Document made by the French Southern and Antarctic Lands © TAAF Lands © Southern and Antarctic the French made by Document l l assessm iona asse a g ss b e e m lo n r • Size : 45-50 cm t F G e A n t A SOUTHERN FULMAR T • Wingspan : 114-120 cm Fulmarus glacialoides • Weight : 0.7-1kg Order : Procellariiformes — Family : Procellariidae as the ... It is also known GEOGRAPHIC RANGE : The species can be seen in the Southern Ocean but breeds on the coasts of Antarctica and outlying glaciated islands. HABITAT : Southern Fulmars nest on steep rocky slopes and cliff sides, mainly on the coast and on the Antarctic continent. They are highly nomadic outside the breeding season, generally moving north to open waters south of 30°S. © S. BLANC DIET : They eat krill, fish and squid depending on available prey. They also consume carrion and discards from Fulmar Antarctic fishing vessels. BEHAVIOR : REPRODUCTION : Most food is taken by surface-seizing whilst in The breeding season begins in November and egg- flocks. They also skim the surface in low flight laying takes place during the first two weeks of with their beak open. They also sometimes dive December. They breed in colonies on steep rocky at shallow depths to catch their prey. They are slopes and precipitous cliffs on sheltered ledges rather solitary birds that can form small groups or in hollows, sometimes with other species of outside the breeding season. Paired birds tend to petrels. Nests are a gravel-lined scrape in which © S. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

SEAPOP Studies in the Lofoten and Barents Sea Area in 2006

249 SEAPOP studies in the Lofoten and Barents Sea area in 2006 Tycho Anker-Nilssen Robert T. Barrett Jan Ove Bustnes Kjell Einar Erikstad Per Fauchald Svein-Håkon Lorentsen Harald Steen Hallvard Strøm Geir Helge Systad Torkild Tveraa NINA Publications NINA Report (NINA Rapport) This is a new, electronic series beginning in 2005, which replaces the earlier series NINA commissioned reports and NINA project reports. This will be NINA’s usual form of reporting completed research, monitoring or review work to clients. In addition, the series will include much of the institute’s other reporting, for example from seminars and conferences, results of internal research and review work and literature studies, etc. NINA report may also be issued in a second language where appropriate. NINA Special Report (NINA Temahefte) As the name suggests, special reports deal with special subjects. Special reports are produced as required and the series ranges widely: from systematic identification keys to information on important problem areas in society. NINA special reports are usually given a popular scientific form with more weight on illustrations than a NINA report. NINA Factsheet (NINA Fakta) Factsheets have as their goal to make NINA’s research results quickly and easily accessible to the general public. The are sent to the press, civil society organisations, nature management at all levels, politicians, and other special interests. Fact sheets give a short presentation of some of our most important research themes. Other publishing In addition to reporting in NINA’s own series, the institute’s employees publish a large proportion of their scientific results in international journals, popular science books and magazines. -

SEABIRDS RECORDED at the CHATHAM ISLANDS, 1960 to MAY 1993 by M.J

SEABIRDS RECORDED AT THE CHATHAM ISLANDS, 1960 TO MAY 1993 By M.J. IMBER Science and Research Directorate, Department of Conservation, P. 0. Box 10420, Wellington ABSTRACT Between 1960 and hlay 1993,62 species of seabirds were recorded at Chatham Islands, including 43 procellariiforms, 5 penguins, 5 pelecaniforms, and 9 hi.Apart &om the 24 breeding species, there were 14 regular visitors, 13 stragglers, 2 rarely seen on migration, and 9 found only beach-cast or as other remains. There is considerable endemism: 8 species or subspecies are confined, or largely confined, to breeding at the Chathams. INTRODUCTION The Chatham Islands (44OS, 176.5OW) are about 900 km east of New Zealand, and 560 km and 720 km respectively north-east of Bounty and Antipodes Islands. The Chatham Islands lie on the Subtropical Convergence (Fleming 1939) - the boundary between subtropical and subantarctic water masses; near the eastern end of the Chatham Rise - a shallow (4'500 m) submarine ridge extending almost to the New Zealand mainland. Chatham Island seabirds can feed over large areas of four marine habitats: the continental shelf of the Chatham Rise; the continental slope around it; and subtropical and subantarctic waters to the north, east, and south. The Chatham Islands' fauna and flora have, however, been very adversely affected by human colonisation for about 500 years (B. McFadgen, pers. cornrn.). Knowledge of the seabird fauna of the Chatham Islands gained up to 1960 is siunmarised in Oliver (1930), Fleming (1939), Dawson (1955, 1973), and papers quoted therein. The present paper summarises published and unpublished data on the seabirds of the archipelago from 1960 to May 1993, from when visits to these islands depended on infrequent passages by ship from Lyttelton, South Island, to the present, when a visit involves a 2-h scheduled flight from Napier, Wellington, or Christchurch, six dayslweek. -

Fulmarus Glacialis

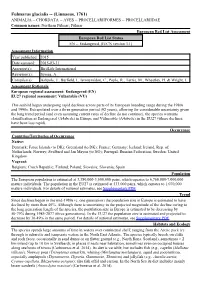

Fulmarus glacialis -- (Linnaeus, 1761) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PROCELLARIIFORMES -- PROCELLARIIDAE Common names: Northern Fulmar; Fulmar European Red List Assessment European Red List Status EN -- Endangered, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Tarzia, M., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Endangered (EN) EU27 regional assessment: Vulnerable (VU) This seabird began undergoing rapid declines across parts of its European breeding range during the 1980s and 1990s. Extrapolated over a three generation period (92 years), allowing for considerable uncertainty given the long trend period (and even assuming current rates of decline do not continue), the species warrants classification as Endangered (A4abcde) in Europe and Vulnerable (A4abcde) in the EU27 (where declines have been less rapid). Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Denmark; Faroe Islands (to DK); Greenland (to DK); France; Germany; Iceland; Ireland, Rep. of; Netherlands; Norway; Svalbard and Jan Mayen (to NO); Portugal; Russian Federation; Sweden; United Kingdom Vagrant: Belgium; Czech Republic; Finland; Poland; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain Population The European population is estimated at 3,380,000-3,500,000 pairs, which equates to 6,760,000-7,000,000 mature individuals. The population in the EU27 is estimated at 533,000 pairs, which equates to 1,070,000 mature individuals. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Trend Since declines began in the mid-1980s (c. one generation) the population size in Europe is estimated to have declined by more than 40%. -

An Assessment for Fisheries Operating in South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands

FAO International Plan of Action-Seabirds: An assessment for fisheries operating in South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands by Nigel Varty, Ben Sullivan and Andy Black BirdLife International Global Seabird Programme Cover photo – Fishery Patrol Vessel (FPV) Pharos SG in Cumberland Bay, South Georgia This document should be cited as: Varty, N., Sullivan, B. J. and Black, A. D. (2008). FAO International Plan of Action-Seabirds: An assessment for fisheries operating in South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands. BirdLife International Global Seabird Programme. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, UK. 2 Executive Summary As a result of international concern over the cause and level of seabird mortality in longline fisheries, the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) Committee of Fisheries (COFI) developed an International Plan of Action-Seabirds. The IPOA-Seabirds stipulates that countries with longline fisheries (conducted by their own or foreign vessels) or a fleet that fishes elsewhere should carry out an assessment of these fisheries to determine if a bycatch problem exists and, if so, to determine its extent and nature. If a problem is identified, countries should adopt a National Plan of Action – Seabirds for reducing the incidental catch of seabirds in their fisheries. South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (SGSSI) are a United Kingdom Overseas Territory and the combined area covered by the Territorial Sea and Maritime Zone of South Georgia is referred to as the South Georgia Maritime Zone (SGMZ) and fisheries within the SGMZ are managed by the Government of South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (GSGSSI) within the framework of the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living (CCAMLR).